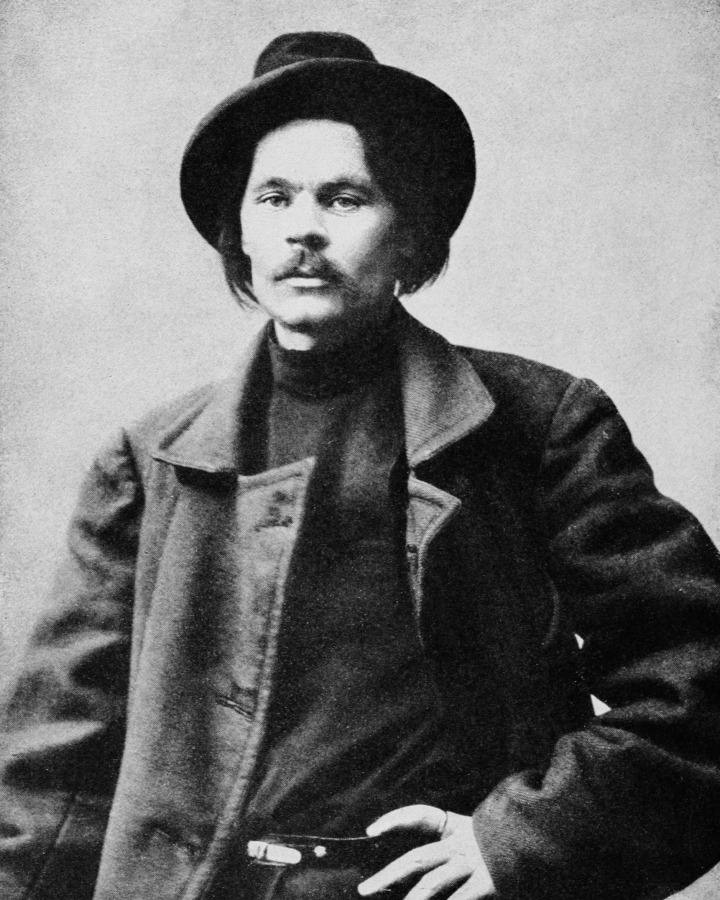

‘Gorki on Films’ (1896) from New Theatre and Film. Vol. 4 No. 1. March, 1937.

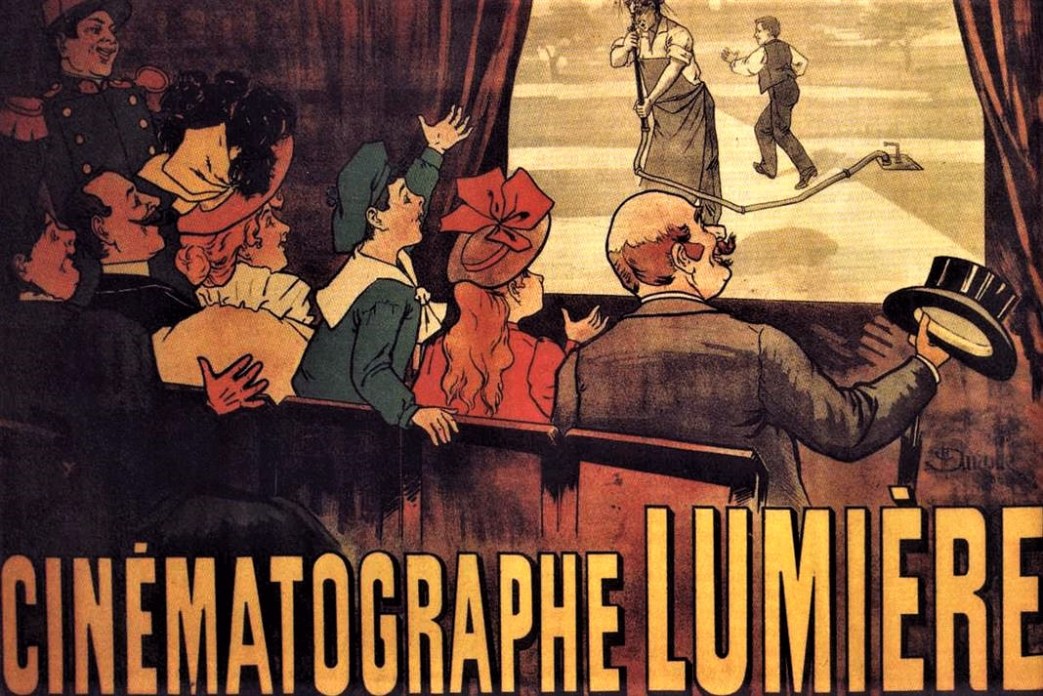

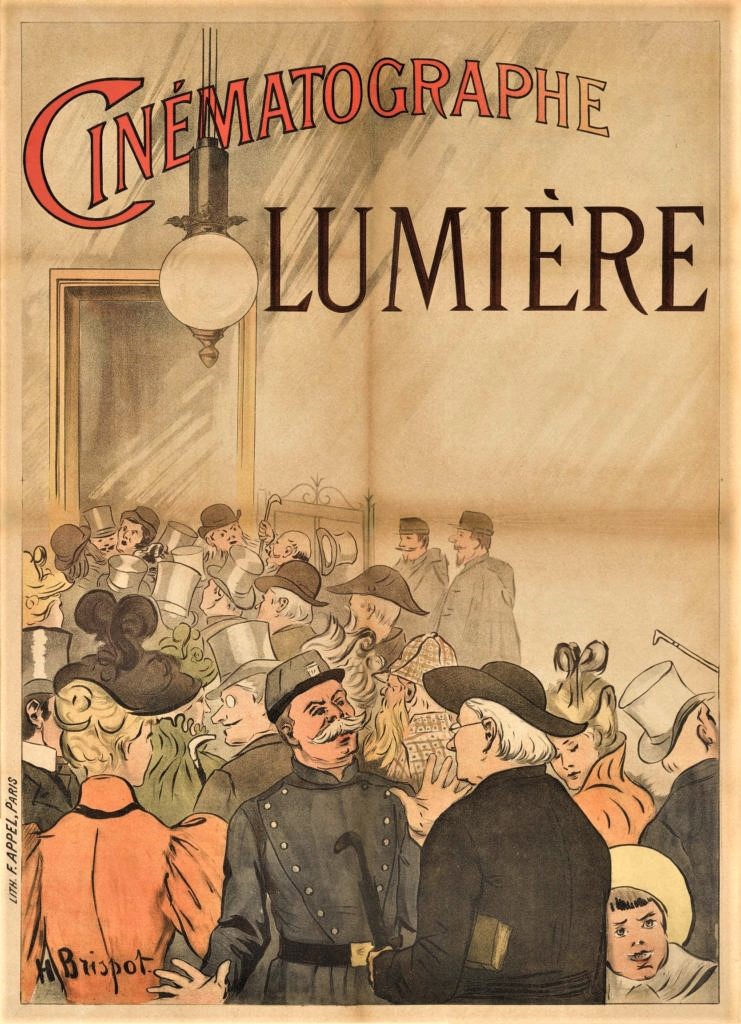

(In 1896 Maxim Gorki was in Paris. There, he happened to be present at an exhibition of the first moving pictures produced by the great pioneer Lumiere. He wrote two reviews of the occasion, which are among the first moving picture reviews on record. Reprinted by the Soviet film magazine, Kina Art, they are not to be found in any of the editions of Gorki’s collected works. The English translation is by Leonard Mins. -THE EDITORS)

I am afraid I am an undependable correspondent – without finishing the description of the factory department, I am writing about the cinematograph. But possibly I will be excused for wanting to give you my fresh impressions.

The cinematograph is a moving photograph. A beam of electric light is projected on a large screen, mounted in a dark room. And a photograph appears on the cloth screen, about two and a half yards high and a yard and a half high. We see a street in Paris. The picture shows carriages, children, pedestrians, frozen into immobility, trees covered with leaves. All of these are still. The general background is the gray tone of an engraving; all objects and figures seem to be 1/10th of their natural size.

And suddenly there is a sound somewhere, the picture shivers, you don’t believe your own eyes.

The carriages are moving straight at you, the pedestrians are walking, children are playing with a dog, the leaves are fluttering on the trees, and bicyclists roll along…and all this, coming from somewhere in the perspective of the picture, moves swiftly along, approaching the edge of the screen, and vanishes beyond it. It appears from outside the screen, moves to the background, grow, smaller, and vanishes around the corner of the building, behind the line of carriages…In front of you a strange life is stirring, the real, living, feverish life of a main street of France, life which speeds past between two lines of many-storied buildings, like the Terek at Daryal, and nevertheless it is tiny , gray, monotonous, inexpressibly strange.

And suddenly it disappears. Your eyes see a plain piece of white cloth in a wide black frame, and it seems as if nothing had been there. You feel that you have imagined something that you had just seen with your own eyes- and that’s all. You feel indefinably awestruck.

And again another picture. A gardener is watering flowers. The stream of water issuing from the hose falls upon the leaves of the trees, on flowerbeds, on the grass, the flowerpots, and the leaves quiver under the spray.

A little boy, poorly dressed, his face in a mischievous smile, enters the garden and steps on the hose behind the gardener’s back. The stream of water becomes thinner and thinner. The gardener is perplexed; the boy can hardly keep from breaking into laughter- his cheeks are puffed out with the effort. And at the very moment that the gardener brings the nozzle close to his nose to see what’s the matter, the boy takes his foot off the hose! The stream of water hits the gardener in the face- you think the spray is going to hit you, too, and instinctively shrink back…But on the screen the wet gardener chases the mischievous boy; they run far away, growing smaller, and finally at the very edge of the picture, almost ready to fall to the floor, they grapple with each other. Having caught the boy, the gardener pulls him by the ear and spanks him…They disappear. You are impressed by this lively scene, full of motion, taking place in deepest silence.

Another new picture on the screen. Three respectable men are playing whist. One of them is a clean-shaven gentleman, with the visage of a high government official, laughing with what must be a deep, bass laugh. Opposite him a nervous, wiry partner restlessly picks the cards from the table, cupidity in his gray face. The third person is pouring beer that the waiter had brought to the table; the waiter, stopping behind the nervous player, looks at his cards with tense curiosity. The players deal the cards and…the shadows break into soundless laughter. All of them laugh, even the waiter with his hands on hips, quite disrespectful in the presence of these respectable bourgeois. And this soundless laughter, the laughter of gray muscles in gray faces, quivering with excitement, is so fantastic. From it there blows upon you something that is cold, something too unlike a living thing.

Laughing like shadows, they disappear like shadows…

From far off an express train is rushing at you- look out! It speeds along just as if shot out of a giant gun. It speeds straight at you, threatening to run you over. The station-master hurriedly runs alongside it. The silent, soundless locomotive is at the very edge of the picture…The public nervously shifts in its chairs- this huge machine of iron and steel will rush into the dark room and crush everybody in it…But, appearing on the gray wall, the locomotive disappears beyond the frame of the screen, and the string of cars comes to a stop. The usual scene of crowding throngs when a train reaches a station. The gray people soundlessly cry out, soundlessly laugh, silently walk, kiss each other without a sound.

Your nerves are strained; imagination carries you to some unnaturally monotonous life, a life without color and without sound, but full of movement, the life of ghosts, or of people, damned to the damnation of eternal silence, people who have been deprived of all the colors of life, all its sounds, and they are almost all the better for it…

It is terrifying to see this gray movement of gray shadows, noiseless and silent. Mayn’t this already be an intimation of life in the future? Say what you will- but this is a strain on the nerves. A wide use can be predicted, without fear of making a mistake, for this invention, in view of its tremendous originality. How great is its productivity, compared with the expenditure of nervous energy? Is it possible for it to attain such useful application as to compensate for the nervous strain it produces in the spectator? This is an important question, a still more important question in that our nerves are getting weaker and weaker, are growing more and more unstrung, are reacting less and less forcefully to the simple “impressions of daily life” and thirst more and more eagerly for new, strong, unusual, burning, and strange impressions. The cinematograph gives you them- and the nerves will grow cultivated on the one hand, and dulled on the other! The thirst for such strange, fantastic impressions as it gives will grow ever greater, and we will be increasingly less able and less desirous of grasping the everyday impressions of ordinary life. This thirst for the strange and the new can lead us far, very far, and “The Saloon of Death” may have shifted from the Paris of the end of the nineteenth century to the Moscow of the beginning of the twentieth.

I forgot to say that the cinematograph is shown at Aumond’s, the well-known Charles Aumond’s, the former stableman for General Boisdefre, they say.

Up to now our charming Charles Aumond has brought with him only French women “stars” and ten men; his cinematograph exhibits so far very nice pictures, as you see. But, of course, this is not for long, and it is to be expected that the cinematograph will show “piquant” scenes of the life of the Paris demi-monde. “Piquant” here means debauched, and nothing else.

In addition to the pictures mentioned above, there are two others. Lyons: women workers leave a factory. A crowd of lively, moving, gay, laughing women leave the wide gates, run across the screen and vanish. All of them are so nice, with such modest, lively faces, ennobled by toil. And in the dark room they are gazed at by their fellow-countrywomen, intensively gay, unnaturally noisy, extravagantly dressed, with some make-up on their faces, and incapable of understanding their Lyons compatriots.

The other picture is The Family Breakfast. A modest couple with a chubby first-born, “baby”, is sitting at the table.

“She” is making coffee over an alcohol lamp, and with a loving smile looks on while her handsome young husband feeds his son with a spoon, feeds and smiles with the laughter of a happy man. Outside the window the leaves flutter, noiselessly flutter; the baby smiles at his father with all his chubby chin; everything bears the stamp of such a healthy, hearty, simple atmosphere.

And this picture is looked at by women deprived of the happiness of having a husband and children, the gay women “from Aumond’s,” stirred by the astonishment and envy of respectable women for their knowing how to dress, and the contempt, the disgusted feeling produced by their profession. They look on and laugh…but it is quite possible that their hearts ache with anguish. And it is possible that this gray picture of happiness, this soundless picture of the life of shadows is for them the shadow of the past, the shadow of their past thoughts and dreams of the possibility of such a life as this, but a life with bright, sounding laughter, a colorful life. And possibly many of them, looking at this picture, would like to cry, but cannot; they must laugh, for that is their sorrowful profession…

At Aumond’s these two pictures are something in the nature of hard, biting irony for the women of his hall, and will doubtless be removed. I am convinced that they will soon, very soon, be replaced by pictures in a genre more suited to the “Concert Parisien” and the demands of the fair. And the cinematograph, the scientific importance of which is as yet incomprehensible to me, will cater to the tastes of the fair and the debauchery of its hangers-on.

It will show illustrations to the works of De Sade and to the adventures of the Chevalier Fauxblas; it can provide the fair with pictures of the countless falls of Mlle. Nana, Martin Harr is protegee of the Parisian bourgeoisie, the beloved child of Emile Zola. Rather than serve science and aid in the perfection of man, it will serve the Nizhni-Novgorod Fair and help to popularize debauchery. Lumiere borrowed the idea of moving photography from Edison, borrowed, developed and completed it, and probably did not foresee where and for whom his invention would be demonstrated.

It is surprising that the fair has not examined the possibilities of X-rays, and why Aumond, Toulon, Lomache and Co. have not yet utilized them for amusement and diversion. And this omission is a very serious one!

Besides. Possibly tomorrow X-rays will also appear on the screen at Aumond’s, used in some way or other for “belly dances”.

There is nothing in the world so great and beautiful but that mar can vulgarize and dishonor it. And even in the clouds, where formerly ideals and dreams dwelt, they now want to print advertisements-for improved toilets, I suppose.

Hasn’t this been mentioned in print yet?

Never mind-you’ll soon see it.

The New Theater continued Workers Theater. Workers Theater began in New York City in 1931 as the publication of The Workers Laboratory Theater collective, an agitprop group associated with Workers International Relief, becoming the League of Workers Theaters, section of the International Union of Revolutionary Theater of the Comintern. The rough production values of the first years were replaced by a color magazine as it became primarily associated with the New Theater. It contains a wealth of left cultural history and ideas. Published roughly monthly were Workers Theater from April 1931-July/Aug 1933, New Theater from Sept/Oct 1933-November 1937, New Theater and Film from April and March of 1937, (only two issues).

PDF of full issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/usa/pubs/workers-theatre/v4n01-mar-1937-New-Theatre-&-Film.pdf