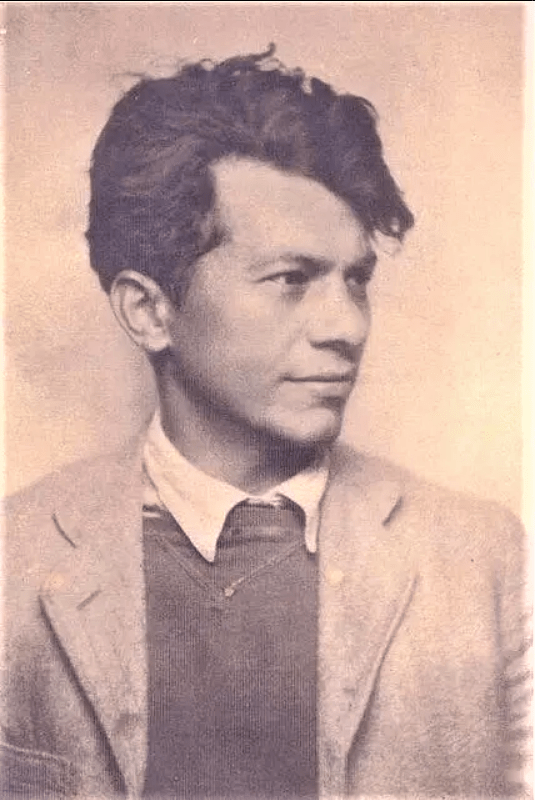

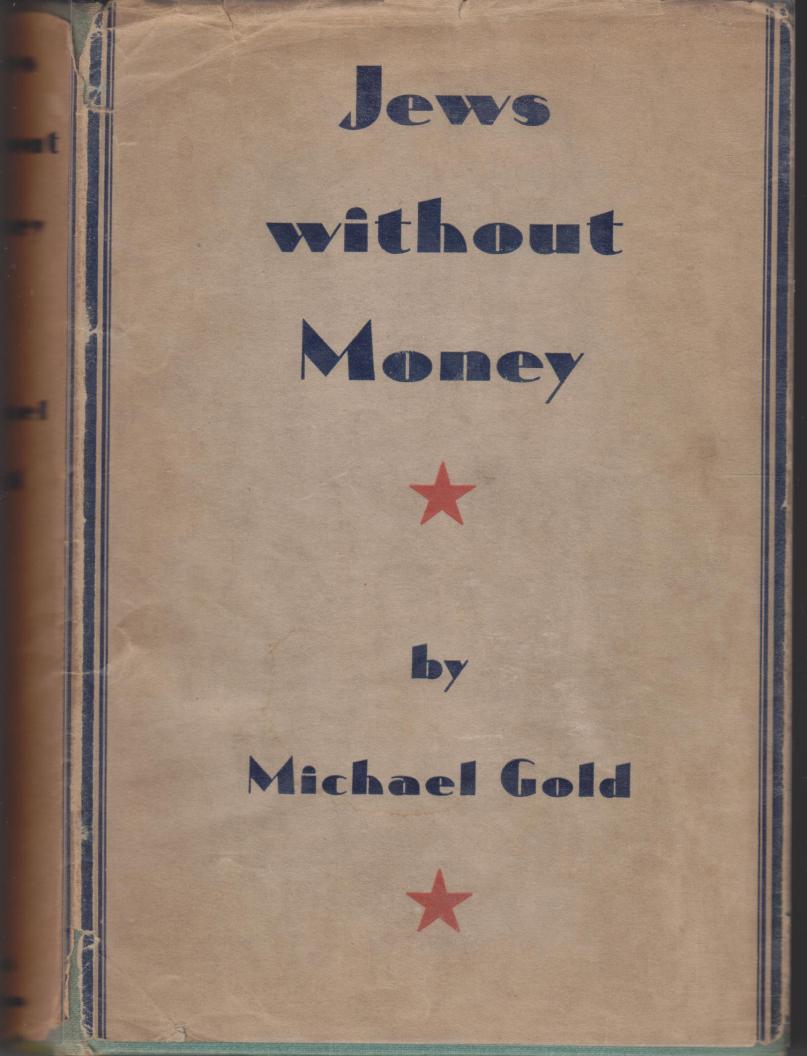

One of the most important essays in U.S. radical literary theory, and where the term “proletarian literature” in America can be dated. This article is also Gold’s coming to terms with his mentor Marx Eastman, publisher of The Liberator and also served as a reply and refutation of Eastman’s 1919 introduction to his ‘Colors of Life’ collection (to be transcribed shortly). Though Gold distanced himself later in slight embarrassment of his early exuberance, it remains a milestone of radical literature and a must-read text for its students. This was the final article written by Irwin Granich who become an editor of the Liberator under as “Michael Gold” the following month.

‘Towards Proletarian Art’ by Irwin Granich (Michael Gold) from The Liberator. Vol. 4 No. 2. February, 1921.

THE APOCALYPSE

IN BLOOD, in tears, in chaos and wild, thunderous clouds of fear the old economic order is dying. We are not appalled or startled by that giant apocalypse before us. We know the horror that is passing away with this long winter of the world. We know, too, the bright forms that stir at the heart of all this confusion, and that shall rise out of the debris and over the ruins of capitalism with beauty. We are prepared for the economic revolution of the world, but what shakes us with terror and doubt is the cultural upheaval that must come. We rebel instinctively against that change. We have been bred in the old capitalist planet, and its stuff is in our very bones. Its ideals, mutilated and poor, were yet the precious stays of our lives. Its art, its science, its philosophy and metaphysics are deeper in us than logic or will. They are deeper than the reach of the knife in our social passion. We cannot consent to the suicide of our souls. We cling to the old culture, and fight against it in our own selves. But it must die. The old ideals must die. But let us not fear. Let us fling all we are into the cauldron of the revolution. For out of our death shall arise glories, and out of the final corruption of this old civilization we have loved shall spring the new race- the Supermen.

A BASIS IN THE MAELSTROM

It is necessary first to discuss our place in eternity. I myself have felt almost mad as I staggered back under the blows of infinity. That huge, brooding pale evil all about me that endless Nothing out of which something seems to have evolved somehow- that nightmare in man’s brain called Eternity- how it has haunted me! Its poison has almost blighted this sweet world I love.

The curse of the thought of eternity is in the brain and heart of every artist and thinker. But they do not let it drive them mad, for they discover what gives them strength and faith to go on seeking its answer. They realize in revelations that the language of eternity is not man’s language, and that only through the symbolism of the world around us and manifest in us can we draw near the fierce, deadly flame.

The things of the world are all portals to eternity. We can approach eternity through the humble symbols of life. Through beasts and fields and rivers and skies, through the common goodness and passion of men. Yet what is Life, then? What is that which my body holds like a vessel filled with fire? What is that which grows, which changes, which manifests itself, which moves in clod and bird and ocean and mountain, and binds them so invisibly in some mystic league of purpose? I have contemplated all things great and small with this question on my lips. And seeking a synthesis for Life, and thus for eternity, I early found that the striving, dumb universe had strained to its fullest, expressiveness in the being of man.

Man was Life become vocal and sensitive. Man was Life become dramatic and complete. He gained and he lost; he knew values, he knew joys and sorrows, and not mere pleasures and pains. He was bad, glad, sad, mad; he was color and form; he contained everything I had not found in the white, meaningless face of pure Eternity. Eternity became interesting only in him. He had desires; he engendered climaxes. He moved me to the soul with his pathos and aspirations. He was significant to me; he made me think and love. Life’s meaning was to be found only in the great or mean days between each man’s birth and death, and in the mystery and terror hovering over every human head. Seeking God we find Man, ever and ever. Seeking answers we find men and women.

IN THE DEPTHS

I can feel beforehand the rebellion and contempt with which many true and passionate artists laboring in all humility will greet claims for a defined art. It is not a mere aristocratic scorn for the world and its mass-yearnings that is at the root of the artists’ sneer at “propaganda.” It is a deeper, more universal feeling than that. It is the consciousness that in art Life is speaking out its heart at last, and that to censor the poor brute- murmurings would be sacrilege. Whatever they are, they are significant and precious, and to stifle the meanest of Life’s moods taking form in the artist would be death. Artists are bitter lovers of Life, and in beauty or horror she is ever dear to them. I wish to speak no word against their holy passion, therefore, and I regard with reverence the scarred and tortured figures of the artist-saints of time, battling against their demons, bearing each a ponderous cross, receiving solemnly in decadence, insanity, filth and fear the special revelation Life has given them.

I respect the suffering and creations of all artists. They are deeper to me than theories artists have clothed their naked passions in. I would oppose no contrary futile dogmas. I would show only, if I can, what manner of vision Life has vouchsafed me, what word has descended on me in the midst of this dark pit of experience, what forms my says and nights might have taken, as they proceed in strange nebular turning towards new worlds of art.

I was born in a tenement. That tall, sombre mass, holding its freight of obscure human destinies, is the pattern in which my being has been cast. It was in a tenement that I first heard the sad music of humanity rise to the stars. The sky above the airshafts was all my sky; and the voices of the tenement neighbors in the airshaft were the voices of all my world. There, in suffering youth, I feverishly sought God and found Man. In the tenement Man was revealed to me, Man, who is Life speaking. I saw him, not as he has been pictured by the elder poets, groveling or sinful or romantic or falsely god-like, but one sunk in a welter of humble, realistic cares; responsible, instinctive, long-suffering and loyal; sad and beaten yet reaching out beautifully and irresistibly like a natural force for the mystic food and freedom that are Man’s.

All that I know of Life I learned in the tenement. I saw love there in an old mother who wept for her sons. I saw courage there in a sick worker who went to the factory every morning. I saw beauty in little children playing in the dim hallways, and despair and hope and hate incarnated in the simple figures of those who lived there with me. The tenement is in my blood. When I think it is the tenement thinking. When I hope it is the tenement hoping, I am not an individual; I am all that the tenement group poured into me during those early years of my spiritual travail.

Why should we artists born in tenements go beyond them for our expression? Can we go beyond them? “Life burns in both camps,” in the tenements and in the palaces, but can we understand that which is not our very own? We, who are sprung from the workers, can so easily forget the milk that nourished us, and the hearts that gave us growth? Need we apologize or be ashamed if we express in art that manifestation of Life which is so exclusively ours, the life of the toilers? What is art? Art is the tenement pouring.out its soul through us, its most sensitive and articulate sons and daughters,. What is Life? Life for us has been the tenement that bore and molded us through years of meaningful pain.

THE OLD MOODS

A boy of the tenements feels the slow, mighty movement that is art stir within him. He broods darkly on the Life around him. He wishes to understand and express it, but does not know his wish. He turns to books, instead. There he finds reflections, moods, philosophies, but they do not bring him peace. They are myriad and bewildering, they are all the voices of solitaries lost and distracted in Time.

The old moods, the old poetry, fiction, painting, philosophies, were the creations of proud and baffled solitaries. The tradition has arisen in a capitalist world that even priests of art must be lonely beasts of prey- competitive and unsocial. Artists have deemed themselves too long the aristocrats of mankind. That is why they have all become so sad and spiritually sterile. What clear, strong faith do our intellectuals believe in now? They have lost everything in the vacuum of logic where they dwell. The thought of God once sustained their feet like rock, but they slew God. Reason was once their star, but they are sick with Reason. They have turned to the life of the moods, to the worship of beauty and sensation, but they cannot live there happily. For Beauty is a cloud, a mist, a light that comes and goes, a vague water changing rapidly. The soul of Man needs some sure and permanent thing to believe, to be devoted to and to trust. The people have that profound Truth to believe in their instincts. But the intellectuals have become contemptuous of the people, and are therefore sick to death.

The people live, love, work, fight, pray, laugh; they accept all, they accept themselves, and the immortal urgings of Life within them. They know reality. They know bread is necessary to them; they know love and hate. What do the intellectuals know?

The elder artists have all been sick. They have had no roots in the people. The art ideals of the capitalistic world isolated each artist as in a solitary cell, there to brood and suffer silently and go mad. We artists of the people will not face Life and Eternity alone. We will face it from among the people. We must lose ourselves again in their sanity.

We must learn through solidarity with the people what Life is.

Masses are never pessimistic. Masses are never sterile. Masses are never far from the earth. Masses are never far from the heaven. Masses go on-they are the eternal truth. Masses are simple, strong and sure. They never are lost long; they have always a goal in each age.

What have the intellectuals done? They have created, out of their solitary pain, confusions, doubts and complexities. But the masses have not heard them; and Life has gone on. The masses are still primitive and clean, and artists must turn to them for strength again. The primitive sweetness, the primitive calm, the primitive ability to create simply and without fever or ambition, the primitive satisfaction and self-sufficiency they must be found again.

The masses know what Life is, and they live on in gusto and joy. The lot of man seems good to them despite everything; they work, they bear children, they sing and play. But intellectuals have become bored with the primitive monotony of Life-with the deep truths and instincts.

The boy in the tenement must not learn of their art. He must stay in the tenement and create a new and truer one there.

THE REVOLUTION

The Social Revolution in the world today arises out of the deep need of the masses for the old primitive group life. Too long have they suppressed that instinct most fundamental to their nature-the instinct of human solidarity. Man turns bitter as a competitive animal. In the Orient, where millions live and labor and die, peace has brooded in the air for centuries. There have never been individuals there, but family clans and ancestor worshipers, so that men have felt themselves part of a mystic group extending from the dim past into the unfolding future. Men have gathered peace from that bond, and strength to support the sorrow of Life. From the solidarity learned in the family group, they have learned the solidarity of the universe, and have created creeds that fill every device of the universe with the family love and trust.

The Social Revolution of today is not the mere political movement artists despise it as. It is Life at its fullest and noblest. It is the religion of the masses, articulate at last. It is that religion which says that Life is one, that Men are one, through all their flow of change and differentiation; that the destiny of Man is a common one, and that no individual need bear on his weak shoulders alone the crushing weight of the eternal riddle. None of us can fail, none of us can succeed.

The Revolution, in its secular manifestations of strike, boycott, mass-meeting, imprisonment, sacrifice, agitation, martyrdom, organization, is thereby worthy of the religious devotion of the artist. If he records the humblest moment of that drama in poem, story or picture or symphony, he is realizing Life more profoundly than if he had concerned himself with some transient personal mood. The ocean is greater than the tiny streams that trickle down to be lost in its godhood. The Revolution is the permanent mood in which Man strains to goodness in the face of an unusual eternity; it is greater than the minor passing moods of men.

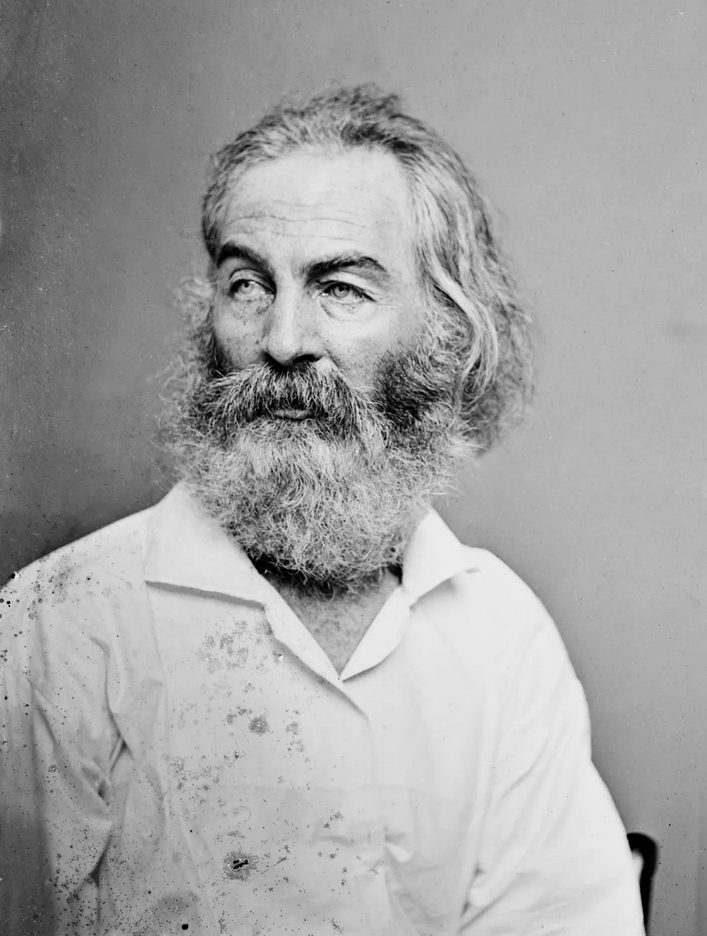

WALT WHITMAN’S SPAWN

The heroic spiritual grandfather of our generation in America is Walt Whitman. That giant with his cosmic intuitions and comprehensions, knew all that we are still stumbling after. He knew the width and breadth of Eternity, and ranged its fearful spaces with the faith of a Viking. He knew Man; how Man was the salt and significance of Eternity, and how Man’s soul outweighed the splendor and terror of the stars. Walt feared nothing; nothing shook his powerful serenity; he was unafraid before the bewildering tragedy of Life; he was strong enough to watch it steadily, and even to love it without end.

Walt dwelt among the masses, and from there he drew his strength. From the obscure lives of the masses he absorbed those deep affirmations of the instinct that are his glory. Walt has been called a prophet of individualism, but that is the usual blunder of literature. Walt knew the masses too well to believe that any individual could rise in intrinsic value above them. His individuals were those great, simple farmers and mechanics and ditch diggers who are to be found everywhere among the masses-those powerful, natural persons whose heroism needs no drug of fame or applause to enable them to continue; those humble, mighty parts of the mass, whose self-sufficiency comes from their sense of solidarity, not from any sense of solitariness.

Walt knew where America and the world were going. He made but one mistake, and it was the mistake of his generation. He dreamed the grand dream of political democracy, and thought it could express in completion all the aspirations of proletarian man. He was thinking of a proletarian culture, however, when he wrote in his Democratic Vistas:

“I say that democracy can never prove itself beyond cavil, until it founds and luxuriantly grows its own forms of art, poems, schools, theology, displacing all that exists, or that has been produced anywhere in the past under opposite influences.”

Walt Whitman is still an esoteric poet to the American masses, and it is because that democracy on which he placed his passionate hope was not a true thing. Political democracy failed to evoke from the masses here all the grandeur and creativeness Walt knew so well were latent in them, and the full growth of which would have opened their hearts to him as their divinest spokesman.

The generation of artists that followed Walt were not yet free from his only fundamental error. Walt, in his poetry, had intuitively arrived at the proletarian art, though his theory had fallen short of the entire truth. The stream of his successors in literature had no such earthy groundwork as his, however. When they wrote of the masses it was not as Walt, the house-builder, the tramp, the worker, had, not as literary investigators, reporters, genteel and sympathetic observers peering down from a superior economic plane. Walt still lived in the rough equalitarian times of a semi-pioneer America, but his successors were caught in the full rising of the industrial expansion. They could not possibly escape its subtle class psychologies.

But now, at least, the masses of America have awakened, through the revolutionary movement, to their souls. Now, at last, are they prepared to put forth those striding, outdoor philosophers and horny-handed creators of whom he prophesied. Now are they fully aware that America is theirs. Now they can sing it. Now their brain and heart, embodied in the revolutionary element among them, are aroused, and they can relieve Walt, and follow him in the massive labors of the earth built proletarian culture.

The method of erecting this proletarian culture must be the revolutionary method from the deepest depths upward.

In Russia of the workers the proletarian culture has begun forming its grand outlines against the sky. We can begin to see what we have been dimly feeling so necessary through these dark years. The Russian revolutionists have been aware with Walt that the spiritual cement of a literature and art is needed to bind together a society, They have begun creating the religion of the new order. The Prolet-Kult is their conscious effort toward this.

It is the first effort of historic Man towards such a culture. The Russians are creating all from the depths upward. Their Prolet-Kult is not an artificial theory evolved in the brains of a few phrase-intoxicated intellectuals, and foisted by them on the masses. Art cannot be called into existence that way. It must grow from the soil of life, freely and without forethought. But art has always flourished secretly in the hearts of the masses, and the Prolet-Kult is Russia’s organized attempt to remove the economic barriers and social degradation that repressed that proletarian instinct during the centuries.

In factories, mines, fields and workshops the word has been spread in Russia that the nation expects more of its workers than production. They are not machines, but men and women. They must learn to express their divinity in art and culture. They are encouraged and given the means of that expression, so long the property of the bourgeoisie.

The revolutionary workers have hammered out, in years of strife, their own ethics, their own philosophy and economics. Now, when their ancient heroism is entering the cankered and aristocratic field of art, there is an amazing revaluation of the old value manifest there. We hear strange and beautiful things from Russia. We hear that hope has come back to the pallid soul of man. We hear that in the workers’ art there are no longer the obsessions and fears that haunted the brains of the solitary artists. There is tranquility and humane strength. The attitude toward love and death and eternity have altered-all the fever is out of them, all the tragedy. Nothing seems worthy of despair to the mass-soul of the Russian workers, that conquered the horrors of the Czardom. They have learned to work and hope. A great art will arise out of the new great life in Russia-and it will be an art that will sustain man, and give him equanimity, and not crucify him on his problems as did the old. The new artists feel the mass-sufficiency, and suffer no longer that morbid sense of inferiority before the universe that was the work of the solitaries. It is the resurrection.

In America we have had attempts to carry on the work of old Walt, but they have failed, and must fail, while the propagandists still lack Walt’s knowledge that a mighty national art cannot arise save out of the soil of the masses. Their appeal has been to the leisured class who happen to be at present our intellectuals.

Such groups as centered around the Seven Arts magazine and the Little Review tried to set in motion the sluggish current of vital American art. The Little Review, preaching the duty of artistic insanity, and the Seven Arts, exhorting all to some vague spirit of American virility, alike failed, for they based their hopes on the studios.

It is not in that hot-house air that the lusty great tree will grow. Its roots must be in the fields, factories and workshops of America-in the American life.

When there is singing and music rising in every American street, when in every American factory there is a drama group of the workers, when mechanics paint in their leisure, and farmers write sonnets, the greater art will grow and only then.

Only a creative nation understands creation. Only an artist understands art.

The method must be the revolutionary method-from the deepest depths upward.

The Liberator was published monthly from 1918, first established by Max Eastman and his sister Crystal Eastman continuing The Masses, was shut down by the US Government during World War One. Like The Masses, The Liberator contained some of the best radical journalism of its, or any, day. It combined political coverage with the arts, culture, and a commitment to revolutionary politics. Increasingly, The Liberator oriented to the Communist movement and by late 1922 was a de facto publication of the Party. In 1924, The Liberator merged with Labor Herald and Soviet Russia Pictorial into Workers Monthly. An essential magazine of the US left.

PDF of full issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/usa/culture/pubs/liberator/1921/02/v04n02-w35-feb-1921-liberator-hr.pdf