October, 1920 report to the Central Executive Committee by Lunacharsky on the work of the Commissariat of Education.

‘The Work of the Commissariat of Education’ by Anatoly Lunacharsky, Commissar of Education from Soviet Russia (New York). Vol. 3 No. 22. November 27, 1920.

THE work of popular education, from the very moment when it was called into being by the November Revolution, was immediately confronted with great difficulties which can be classified into three most important groups. In the first place, a radical transformation of the old school was an imperative necessity, For the old school was a political school, definitely dominated by the cultural and political spirit of the bourgeoisie and gentry, of czarism and the clergy. This was the first difficulty, since there are very few works on the Socialist school in world literature. As far as theory is concerned, we had to deal in this case with an almost unexplored field. What source of light did we have to guide us on the untrodden paths? A page and a half written by Marx in his youth for the Geneva Congress, and a few scattered phrases! Instruction in the old school had, of course, something in common with education, but the school was founded on principles which aimed to give this education with a mixture of pseudoeducation, with subjects harmful in so far as they were useless but consumed a great deal of time, or with clear corrupt subjects, such as religious instruction. While in the secondary and higher schools the minds of the students were poisoned with distorted science, the teachers in. the elementary schools were torn between two incompatible tasks — to teach literacy and yet to leave the pupils in complete ignorance. We undertook to eradicate these vices, and we put forth the idea of the general school.

We instituted the single labor school which was to lead everyone, irrespective of origin, through all the school grades. And we made the schools popular, within reach of all. This meant not only free tuition, but also breakfast and lunches at the schools, free school supplies, etc. We had to go even further, to furnishing shoes and clothing. We wanted the people to know what the Soviet power was bringing. For we have a reply to all superficial attacks, that we “promised this or that, but did not fulfill it.” We reply: we would have accomplished it if we were not diverted by the attempts to strangle us. Formally, the school net of Russia is growing rapidly. The old school buildings are in horrible condition, are badly in need of repairs. Many school buildings in the cities have been taken over for hospitals or military institutions. As soon as we have a sufficient number of schools we will immediately make school attendance obligatory.

The single school does not mean a uniform school. The single school is one which gives equal entrance rights to all, and equal rights after graduation. But we proposed at the same time, that the schools, particularly the secondary schools, should be of different kinds. We deemed it possible, and even recommended that the higher classes of the secondary schools should have two or three divisions, so that the pupils could choose one or another specialty according to their inclinations. Owing to the categorical demand of our economic commissariats we were compelled to allow pupils over 14 years of age to transfer from a general school to a trade or technical school. We have these trade and technical schools, in addition to the schools of general education. Along with this we improved the schools by eliminating the useless subjects, such as ancient languages and religious instruction, by doing away with separate schools for boys and girls, and, lastly, by abolishing the old school discipline.

But the newest feature which even some of our cultured comrades do not yet fully comprehend, is the principle of the so-called school of labor. This term was in many cases completely misunderstood. It was taken to mean that theoretical instruction and books should be completely excluded from the school, and that they should be replaced by productive toil in form. In reality we did not at all intend such a transformation of the schools. Essentially, the principle of the labor school includes two main ideas. The first contends that knowledge should come through toil, that the children should through their own activity discover and reproduce what they learned from books. Using at first the play instinct, the games should be made more and more serious, and, finally, the pupils should be familiarized with the subjects of their studies through excursions, observations, and so forth.

In this way may be learned the whole history of human toil. In connection with this, the technical side, say, of the organization of a factory, may also be taken up, starting with the delivery of fuel, of raw materials, of the basic types of motors, etc. It would also be possible in this way to introduce the principles of labor discipline. We can thus ignore the nature of the erstwhile capitalist system and turn directly to the present system. We have never given up this idea, for the school of labor of the industrial type is the only communist school.

And now for the elementary schools. Most of the elementary schools are situated in the villages, and productive toil in these must be of a somewhat different character from that in the secondary schools. There should be moderate self-service in these, for instance, keeping the school in order. With regard to these schools I feel that we must welcome them, and in the villages we must also see to the development of their agricultural aspect. With respect to this we have already taken energetic steps, and have tried to come to some understanding with the Commissariat of Agriculture in regard to the mobilization of agricultural experts, of whom we have but a small number, to provide instruction in agriculture for the village school teachers, the majority of whom have no such knowledge.

Our village school teachers have absolutely no knowledge of agriculture. At present steps have already been taken to improve this condition. Every fall and spring, new schools and lecture-courses for teachers are opened to instruct them in the principles of toil in elementary schools. In this respect the Commissariat of Education has already some achievements to its credit. We have data showing that the mass of our teachers, with very few exceptions, have become adherents of the Soviet power, have renounced sabotage and are working with the Soviets. At all the congresses of school teachers you will find just as much enthusiasm as in our factories and workshops. They are eagerly following the instructions and directions coming from the center.

I will quote to you some figures which illustrate the school situation in a general way. In 1911, the last year for which complete statistical data are available, there were 55,846 elementary schools. In 1919 we had 73,859 such schools, that is, we increased their number almost 50 per cent. And for the present year their number has increased to about 88,000. These schools take care of about 60 to 65 per cent of the total number of children in Russia. The actual school attendance was not high, owing to the terrible conditions last winter, but on the whole it extended to 5,000,000. The number of pupils increased very rapidly. The schools under the czar could only take care of three and a half million children, while our schools take care of five and a half million.

The number of second grade schools increased very little, because we cannot open new schools. The total number is 3,600. We have about half a million pupils in second grade schools, which is only seven to eight per cent of the total number of children of this age. In this respect the situation is extremely bad. Even if we would exclude all the children of the bourgeoisie and petty bourgeoisie, even then, the vast majority of the children of the workmen and peasants would be left outside of these schools. It is disgraceful, and we must candidly admit it; we are forced to open two-year schools for children to give them at least some education, so that this generation may not be condemned to utter ignorance.

The figures on the training of a teaching-staff are very eloquent. Immense energy was displayed, but it must be remembered that we can not rapidly increase the number of teachers, even though we have drawn into this work a large number of persons who were excluded from this profession under the czar. There were 21 higher pedagogical schools under the czar, while we have 55. The total number of schools increased considerably, and the number of students rose from 4,000 to 34,000. I can tell you that of these 34,000 — under present terrible conditions when people are condemned to starvation, and when such studies can be undertaken only by those who have not been coddled and have not been drawn into service in some other Soviet institution — we have 10,305 persons who are so completely and diligently devoting themselves to school-work that they have proven themselves deserving of social insurance (scholarship), which is given under the strictest control, and cannot be obtained by those who do not merit it We have thus achieved a certain degree of success in this respect. But we must accomplish a great deal more than this. We need an enormous army of teachers. We have 400,000 educational workers, and we need more than a million.

Besides we also have kindergartens. Colossal efforts have been made in this direction, and we are inclined to be proud of this. It should, however, be mentioned that under the czar nothing had existed in the field of pre-school endeavor. I do not speak here of the few kindergartens, model homes for children, of a certain number of charity institution which were established in large cities by rich merchants, and several schools of the Froebel type for children of the rich. In 1919 we had 3,623 kindergartens and about 1,000 kindergartens are being added every year.

I shall now turn to the higher schools. These present an even more difficult task than the secondary schools. For some time the professors were with our enemies. The students took part in insurrections against us, and the professors participated in all kinds of plots. Every time that the Whites appeared at Samara or Saratov the professors were their main support. They sent statements abroad vilifying us. And when we came to them they hid in a shell. But the professors are indispensable, and we are confronted in this respect by a problem similar to that presented by the military department. Comrade Trotsky was right when he said that no army was ever betrayed as much as the Red Army. But the Red Army was nevertheless successful. This is also the case in the higher schools. A change is already taking place, and not solely through the appointment of new men. I could mention a large number of distinguished men — I do not speak here of our splendid friend, the deceased Timiriazev, whose clear views and perspicacity were amazing — I could mention a score of scientists who have really become Soviet adherents. In Petrograd the effect was soon visible. The scientific life of Petrograd has risen. The same effect occurred among the students. Petrograd sets the pace. The first students conference was held there, and after listening to a brilliant report by Zinoviev, a definitely “red” resolution was adopted by an enormous majority.

And now for the labor colleges! At present we manage them in such a way that they are open only to workers who are recommended by labor organizations. We take them into the school, and to a certain extent we subject them to rigid discipline. The students of a labor college have no right to miss any lecture without serious causes, and they must pass examinations to prove efficiency in their studies.

At present the standard of the labor colleges is quite high, and they are already very promising. But our experience with labor colleges taught also a great deal with regard to the universities in general. Under pressure from the economic commissariats the department of technical and trade education proposed raising the educational level of the workers. With this end in view, a large number of night courses for workmen were opened. Simultaneously, we took the question of the necessity of increasing the number of middle and higher engineers. We inquired about the number of engineers necessary, and the Council of National Economy made very serious demands upon us. According to its calculations the schools must give 3,600 new engineers each year. To satisfy this need of the country, the Department of Technical Education decided, first of all, to obtain the right to free engineering students of the last two years from all outside work, to provide them with rations, and to feed their professors, but at the same time to place them under military discipline and punish them as deserters if they did not attend to their work. These measures are of course extraordinary, but they are dictated by present conditions, and thanks to them we graduated over 3,000 engineers this year. We know that we need physicians as well as other specialists, and we have therefore also decided to assure food to all the collaborators in the medical colleges, with the result that the number of students has increased threefold.

The czarist government looked upon the universities as explosive centers, but we have nothing to fear from them, and we go on opening new universities. Thus we have already 21 universities instead of 15. Of the new universities, three or four may be considered to be functioning normally. The Turkestan and Ural universities, which are still in the process of organization, will, in the near future, be in a position to do effective work. We have, just as before the Revolution, four medical universities and three archeological universities. Of veterinary institutes we have six instead of two. The number of professors has increased to 1,644, because we have promoted all the lecture-instructors to the rank of professors.

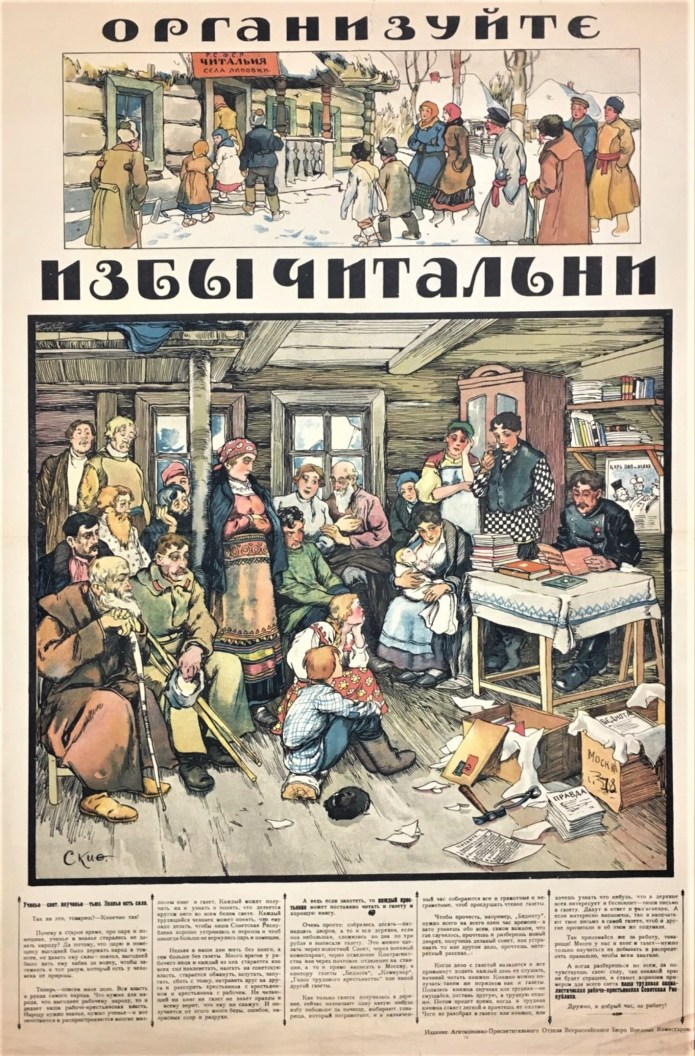

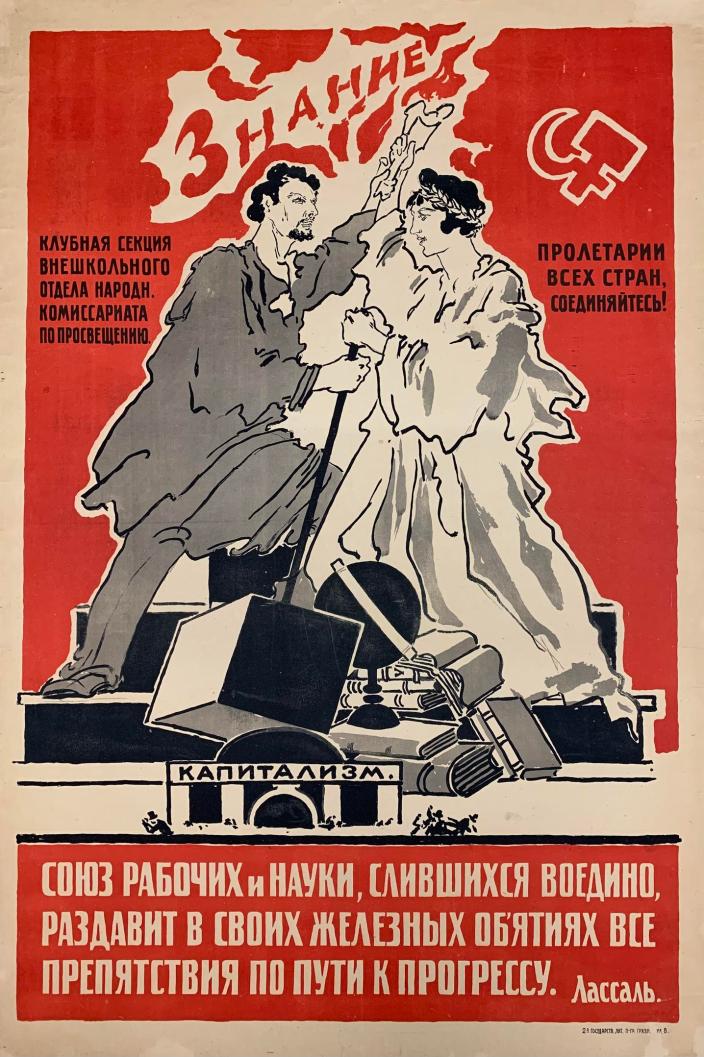

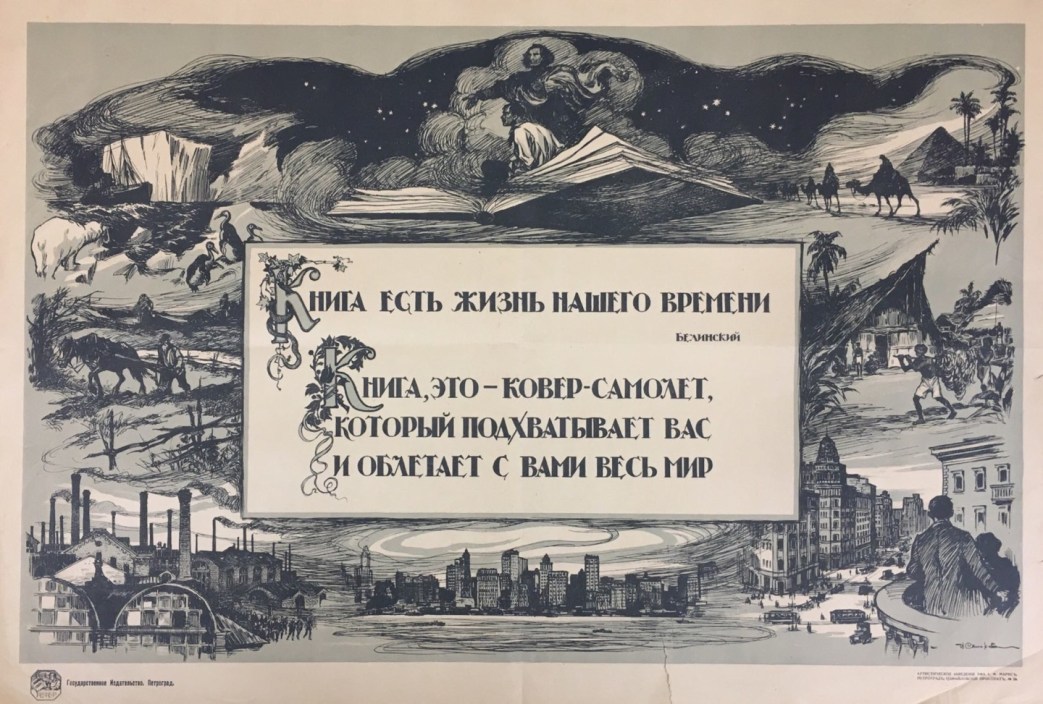

I will now speak of the work outside of the schools, which is of vast importance. All of you know that we can not at present do much in the publishing field. In library work we make use of old books, enriching the school libraries and the general libraries from the stock that we have obtained from the book-stores and from the liquidation of the landlords 9 libraries, which were practically useless. The number of libraries in Russia has greatly increased, and they grow with incredible rapidity. In the Tver Province, for instance, there are over 3,000 libraries. Some provinces have over 1,000 libraries. The total number of libraries in 30 provinces was 13,5000 in 1919, and in these same provinces we now have about 27,000 libraries, not including reading rooms. The increase in the number of libraries is astounding, and I might add that the library attendance, considering present conditions, is no less astounding. However, in the matter of supplying the libraries in the future we are up against great difficulties.

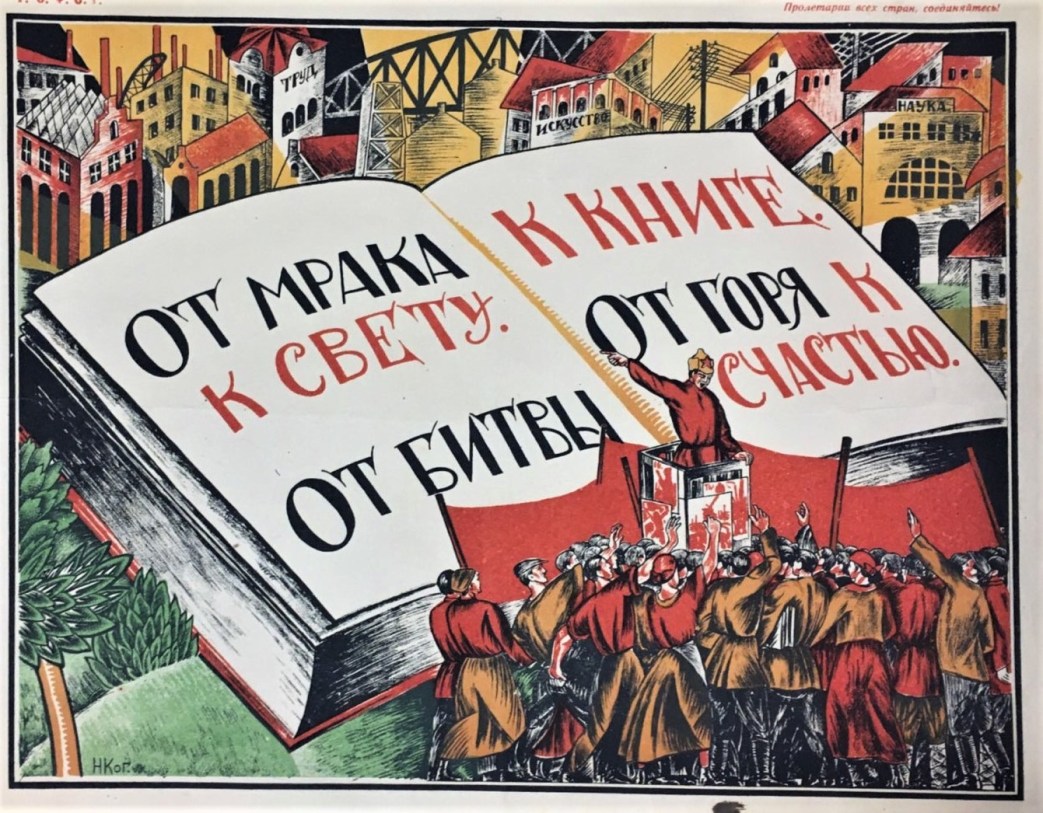

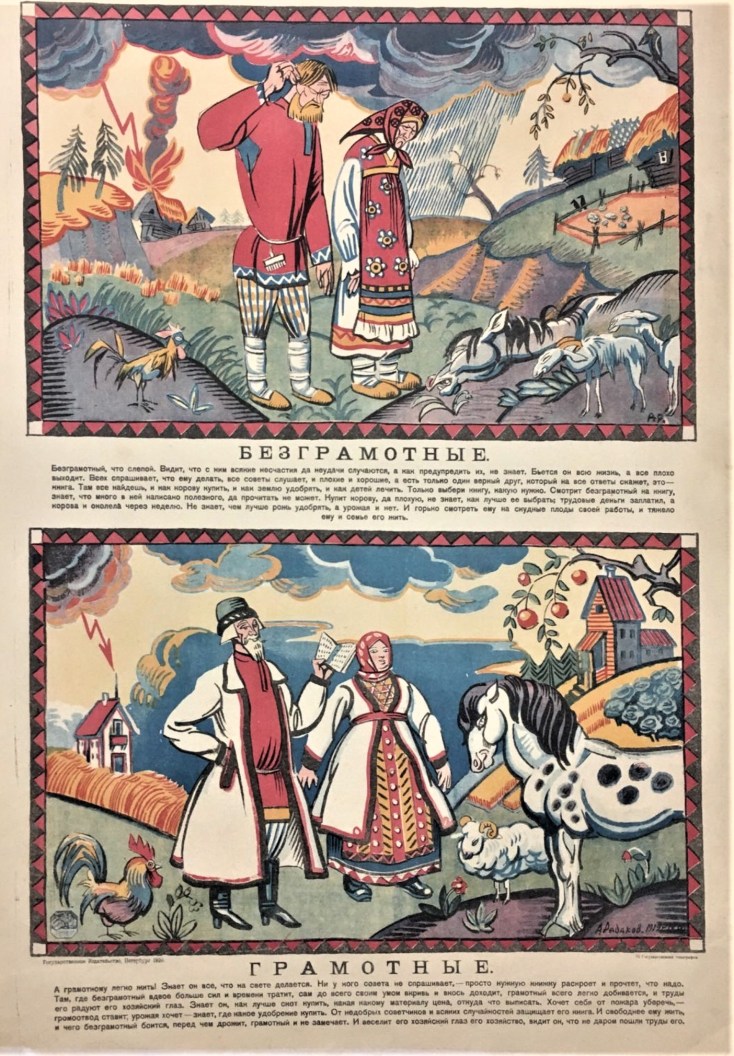

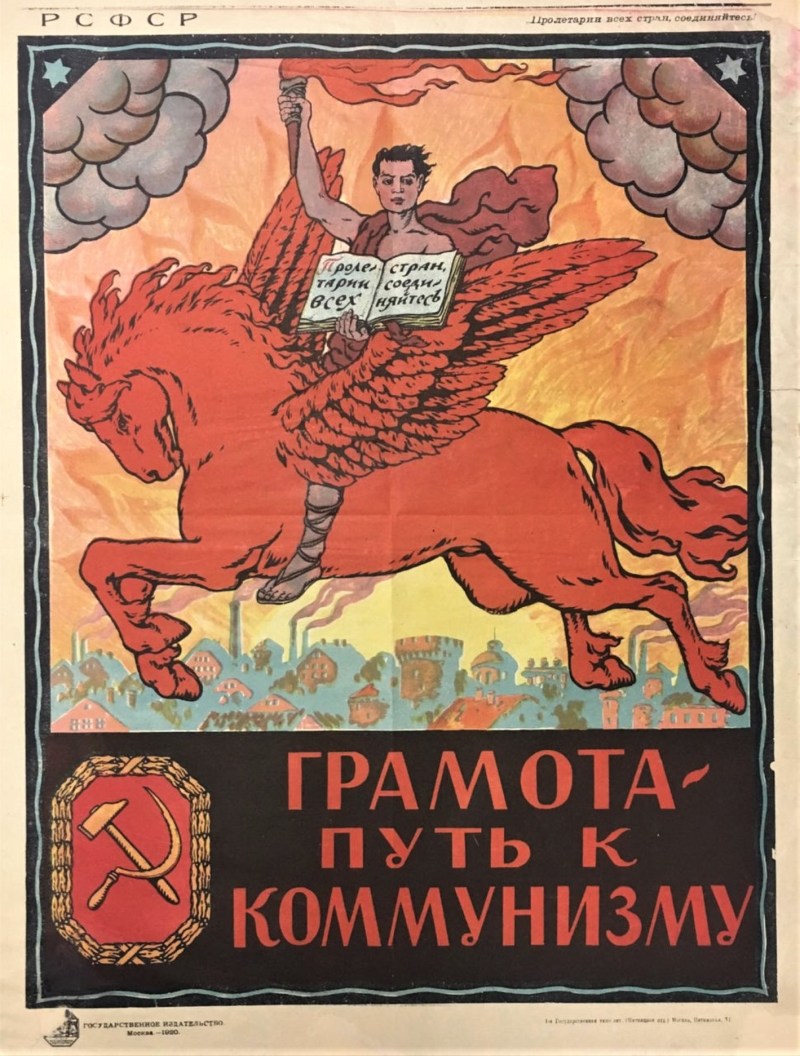

One of the greatest of the Soviet decrees is the decree on the liquidation of illiteracy. In the province of Cherepovetz 58,000 persons have already passed through the schools for illiterates, in Ivanovo- Voznessensk, 50,000 persons. In the city of Novozybkov there are no more illiterates above the age of 40. In Petrograd also there will soon be no illiterates. We have not enough reading primers. However, at present 6 1/2 million primers have already been printed or are on the press.

A special resolution which I proposed two years ago at the Eighth Congress, and which was then adopted, stated that the People’s Commissariat of Education should, under the present conditions, be an organ of Communist education, and that the Communist Party should be closely connected, since this Commissariat is an organ of education and since education must mean Communist education. And to the extent to which the Party carries on propaganda and agitation it should make full use of the apparatus of the People’s Commissariat of Education. But we made very slow progress in this direction, and the Commissariat of Education suffered thereby. Vladimir Ilyich (Lenin) has many times pointed out the plain duty of the party to attract the teachers, as they come nearer to us, to educational and political work; and to compel those teachers who do not come nearer to us to read the decrees and to spread our literature. A good start was then made by the extra-mural division. The extra-mural division was instructed to organize, conjointly with the provincial party committees, courses on the struggle with Poland. This was an absolutely new thing, because the extra-mural teachers had to undertake work of a new type in cooperation with the Party and under the direction of party members, to present the history of Poland, the present social order of Poland, the causes of the war with Poland, etc. In this respect we had considerable success which proves that when the Party supports us we can accomplish a great deal of work, considerably more work than without such support. Indeed, in this work we made a discovery. In 29 provinces, in each of which we opened a school, we passed 2,381 agitators in one month, specialists on the Polish question, and all these agitators were assigned by the Party to the front or for work in the interior. As a further illustration of my thought, I will point out how energetically the sub-divisions of the Commissariat of Education work when they have the support of the Party. Thus, for instance, when it was decided to open new educational institutions in honor of the Third Internationale, when this slogan was issued with Comrade Kalinin’s and my own signature, the results exceeded all our expectations. We were able to achieve unprecedented results in the sense of opening new educational institutions. We had demanded that these institutions be situated in equipped buildings and that they be provided with school supplies. And we now have 23 schools, 164 homes for children, 20 kindergartens, etc. In short, 316 educational institutions sprang up like mushrooms. They all bear the name of the Third Internationale, and this has immense propaganda value.

I shall mention another important step. In the first place, we have just now been entrusted with the food campaign. We ourselves offered to carry on this campaign by means of placards, theatrical performances, literature, and agitation of a scientific character. We threw our extra-mural and school forces into the mass of the peasantry, and have thus helped the Commissariat of Food in its struggle for the grain quotas. We have achieved a number of concrete results in this respect. But one of the most pleasant results is the fact that we now have textbooks which will be a great help in the work of training agitators. With the aid of the Central Committee of the Party a book of 200 pages was written, set in type, put on the press and printed — all in eight days. This shows what we can do if we but will it.

One of the brightest aspects of the activity of the Commissariat of Education was manifested in the care of art monuments and museums. In particular, amazing work has been done in the field of repairing antique buildings. There has been a large increase in the number of museums. At present there are 119 provincial museums, as against 31 of the old regime. Even the museum experts declare that they are amazed and fascinated by the eagerness to collect and to preserve antiques which is shown by the mass of the people of Soviet Russia and by all the organs of the Soviet power. The Ermitage has been enlarged to one and a half times its previous size.

Then comes the division of music. The number of schools has remained the same, but the schools were reorganized, and the number of students has increased. About 9,000 persons above the age of 16 are now studying music.

In the theatrical field we have accomplished great work, but to breathe in new life means to get a new repertoire. The new theatre will be created by new dramatists. In this respect the only thing to do is to write new plays. For the present we have removed from the theatres the objectionable elements.

I once asked Comrade Guilbeaux how many peasant theaters there are in France. In all of France there are only 113 peasant theaters, while in the province of Kostrorha alone we have 400 peasants theaters and throughout Russia there are 3,000 peasant theaters.

The entire People’s Commissariat of Education, with its teachers and educators, is at present inspired by a strong desire to work, and is on the right path for this work. Therefore, if the Commissariat is given support great activity will be shown, and I am sure that the work will not be worse than in any other department. I hope that this report will mark a turning point. If we prove that under such difficult conditions the Communists, the Soviet power, does not overlook the work of education, and that we can even effect important achievements, I assure you that this will mean a colossal victory against our enemies and among our friends. In the field of education we must therefore display the maximum effort, and I hope that you will not reject my proposals — Izvestia, October 5, 1920.

Soviet Russia began in the summer of 1919, published by the Bureau of Information of Soviet Russia and replaced The Weekly Bulletin of the Bureau of Information of Soviet Russia. In lieu of an Embassy the Russian Soviet Government Bureau was the official voice of the Soviets in the US. Soviet Russia was published as the official organ of the RSGB until February 1922 when Soviet Russia became to the official organ of The Friends of Soviet Russia, becoming Soviet Russia Pictorial in 1923. There is no better US-published source for information on the Soviet state at this time, and includes official statements, articles by prominent Bolsheviks, data on the Soviet economy, weekly reports on the wars for survival the Soviets were engaged in, as well as efforts to in the US to lift the blockade and begin trade with the emerging Soviet Union.

PDF of full issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/usa/pubs/srp/v3n08-aug-21-1920-soviet-russia.pdf