In a major piece Debs, the leading, though not leader of, U.S. Socialists weighs in on the split in I.W.W. between the Detroit and Chicago wings; the struggle in the Socialist Party over ‘sabotage’ and its Left and Right; the divisions in the labor movement among the Western Federation of Miners, the Industrial Workers of the World and the American Federation of Labor; and the failure to achieve unity between the Socialist and Socialist Labor Parties with ‘a plea for solidarity.’

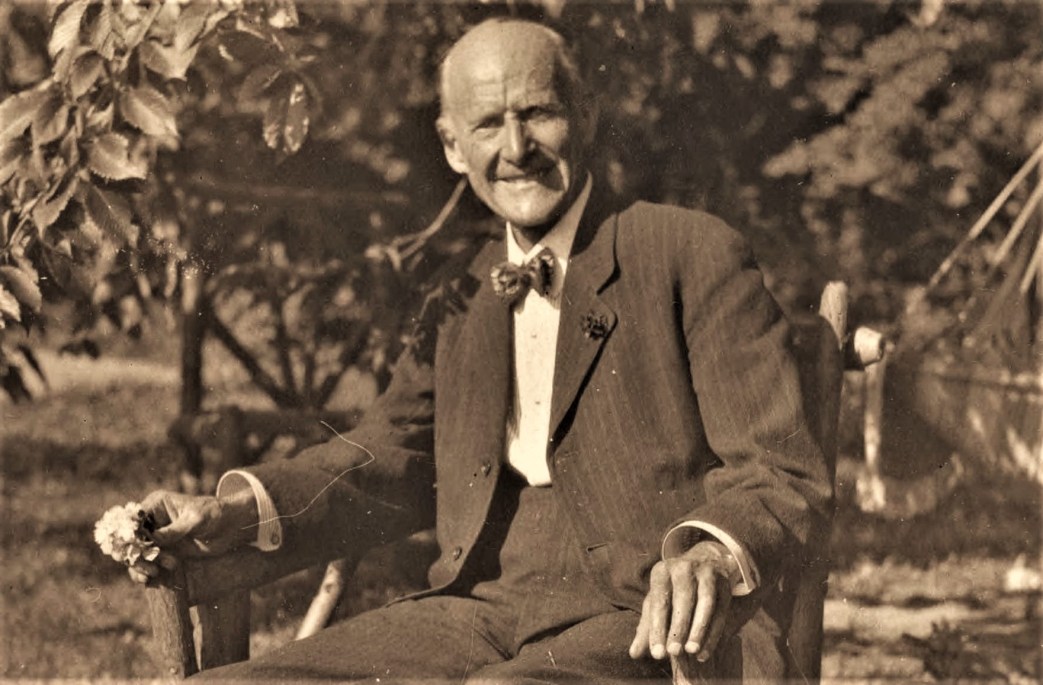

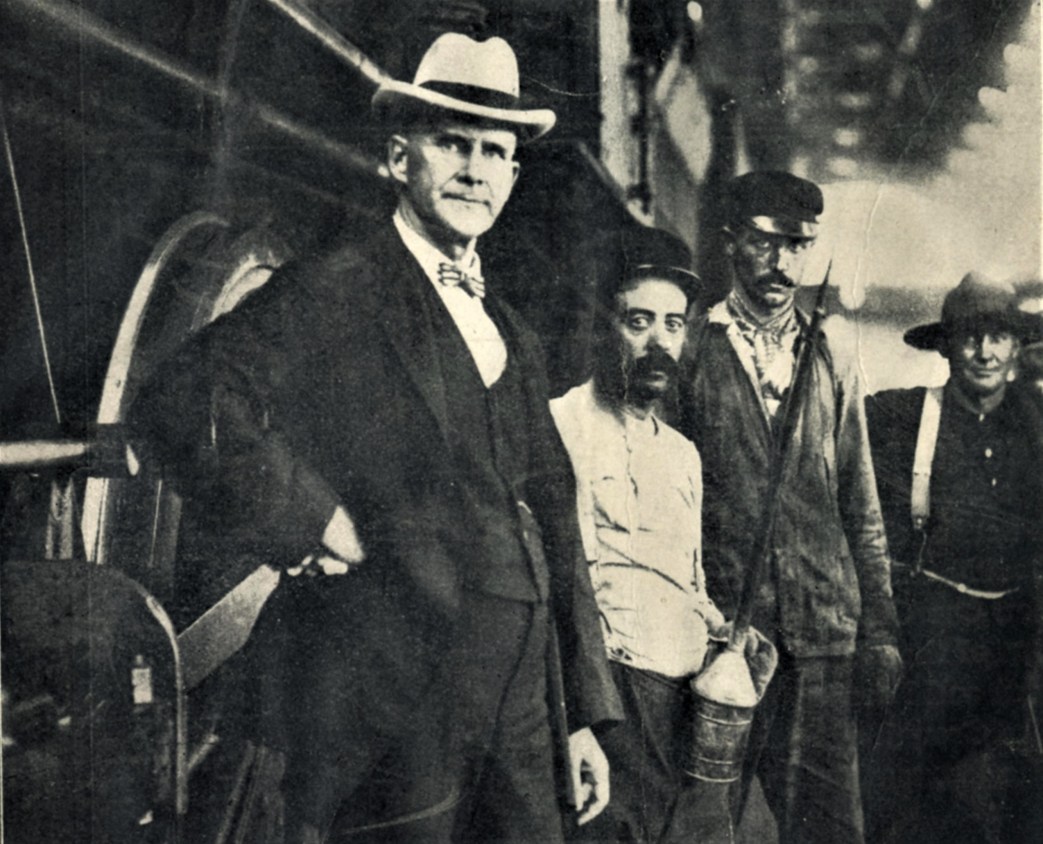

‘A Plea for Solidarity’ by Eugene V. Debs from the International Socialist Review. Vol. 14 No. 9. March, 1914.

“Solidarity—a word we owe to the French Communists and which signifies a community in gain and loss, in honor and dishonor, a being (so to speak) all in the same bottom—is so convenient that it will be in vain to struggle against its reception. ’—Trench.

O the foregoing Webster adds the following definition: “An entire union, or consolidation of interests and responsibilities; fellowship.”

The future of labor, the destiny of the working class, depends wholly upon its own solidarity. The extent to which this has been achieved or is lacking, determines the strength or weakness, the success or failure, of the labor movement.

Solidarity, however, is not a matter of sentiment, but of fact, cold and impassive as the granite foundation of a skyscraper. If the basic elements, identity of interest, clarity of vision, honesty of intent, and oneness of purpose, or any of these, is lacking, all sentimental pleas for solidarity and all efforts to achieve it will be alike barren of results.

The identity of interest is inherent in the capitalist system and the machine process, but the remaining elements essential to solidarity have to be developed in the struggle necessary to achieve it, and it is this struggle in which our unions and parties have been torn asunder and ourselves divided and pitted against each other in factional warfare so bitter and relentless as to destroy all hope of solidarity if the driving forces of capitalism did not operate to make it ultimately inevitable. This struggle has waxed with increasing bitterness and severity during the years since the I.W.W. came upon the scene to mark the advent of industrial unionism to supplant the failing craft unionism of a past age.

But there is reason to believe, as it appears to me, that, as it is “darkest just before the dawn,” so the factional struggle for solidarity waxes fiercest just before its culmination. The storm of factional contention, in which diverse views and doctrines clashed and were subjected to the ordeal of fire, in which all the weapons of the revolution must be forged and tempered, has largely spent itself, and conditions which gave rise to these contentions have so changed, as was pointed out by the editor in the February Review, that unity of the revolutionary forces now seems near at hand.

Industrial unionism is now, theoretically at least, universally conceded. Even Gompers himself now acknowledges himself an industrial unionist. The logic of industrial development has settled that question and the dissension it gave rise to is practically ended.

For the purpose of this writing the proletariat and the working class are synonymous terms. I know of no essential distinction between skilled and unskilled salary and wageworkers. They are all in the same economic class and in their aggregate constitute the proletariat or working class, and the hair-splitting attempts that are made to differentiate them in the class struggle give rise to endless lines of cleavage and are inimical if not fatal to solidarity.

Webster describes a proletaire as a “low person,” “belonging to the commonalty; hence, mean, vile, vulgar.” This is a sufficiently explicit definition of the proletaire by his bourgeois master, which at the same time defines his status in capitalist society, and it applies to the entire working and producing class; hence the lower class.

Such distinction between industrial workers as still persists the machine is reducing steadily to narrower circles and will eventually blot out entirely.

It is now about a century since a few of the skilled and more intelligent workers in the United States began to dimly perceive their identity of interest, and to band themselves together for their mutual protection against the further encroachments of their employers and masters. From that time to this there has been continuous agitation among the workers, now open and pronounced and again under cover and in whispers, according to conditions and opportunities, but never has the ferment ceased and never can it cease until the whole mass has been raised to manhood’s level by the leaven of solidarity.

The net result of an hundred years of agitation, education and unification, it must be confessed, is hardly calculated to inspire one with an excess of optimism and yet, to the keen observer, there is abundant cause for satisfaction with the past and for confidence in the future.

After a century of unceasing labors to organize the workers, about one in fourteen now belongs to a union. To put it in another way, fourteen out of every fifteen who are eligible to membership are still outside of the labor movement. At the same relative rate of growth it would require several centuries more to organize a majority of the working class in the United States.

But there are sound reasons for believing that a new era of labor unionism is dawning and that in the near future organized labor is to come more rapidly to fruition and expand to proportions and develop power which will compensate in full measure for the slow and painful progress of the past and for all its keen disappointments and disastrous failures; and chief of these reasons is the disintegration and impending fall of reactionary craft unionism and the rise and spread of the revolutionary industrial movement.

Never has the trade union of the past given adequate recognition to the vast army of common laborers, and in its narrow and selfish indifference to these unorganized masses it has weakened its own foundations, played into the hands of its enemies, and finally sealed its own doom.

The great mass of common, unskilled labor, steadily augmented by the machine process, is the granite foundation of the working class and of the whole social fabric, and to ignore or slight this proletarian mass, or fail to recognize its essentially fundamental character, is to build without a foundation and rear a house of scantlings instead of a fortress of defense.

That the I.W.W. recognized this fundamental fact and directed its energies to the awakening and stimulation of the unskilled masses which had until then lain dormant, was the secret of its spread and power and likewise of the terror it inspired in the ruling class, and had it continued as it began, a revolutionary industrial union, recognizing the need of political as well as industrial action, instead of being hamstrung by its own leaders and converted, officially at least, into an anti-political machine, it would today be the most formidable labor organization in America, if not the world. But the time has not yet come, seemingly, for the organic change from craft segregation to industrial solidarity. There must needs be further industrial evolution and still greater economic pressure brought to bear upon the workers in the struggle with their masters, to force them to disregard the dividing lines of their craft unions and make common cause with their fellow-workers.

The inevitable split in the I.W.W. came and a bitter factional fight followed. The promising industrial organization was on the rocks. Industrial unionism, which had begun to spread in all directions, came almost toa halt. Fortunately about this time the mass strikes broke out, first in the steel and next in the textile industries. Thousands of unskilled and unorganized workers struck, and for a time both factions of the I.W.W. grew apace and waged the warfare against the mill bosses with an amazing display of power and resources. The important part taken by the Socialist party and its press and speakers in raising funds for the strikers, giving publicity to the issues involved, creating a healthy public sentiment, bringing their political power to bear in forcing a congressional investigation and backing up the I.W.W. and the strikers in every possible way, had much to do with the progress made and the success achieved during this period.

The victory at Lawrence, one of the most decisive and far-reaching ever won by organized workers, triumphantly demonstrated the power and invincibility of industrial unity backed by political solidarity. Without the co-operation and support of the Socialist Party the Lawrence victory would have been impossible, as would also that at Schenectady which followed some time later.

For reasons which came to light after the Lawrence strike, this solidarity was undermined to a considerable extent when the Paterson strike came, and still more so when the Akron strike of the rubber workers followed, both resulting disastrously to the strikers. Both of these strikes were fought with marvelous loyalty and endurance and could and should have been won.

Now again followed the inevitable. The ranks of the I.W.W. were depleted as suddenly as they had filled up. What is there now left of it at McKee’s Rocks, at Lawrence, at Paterson, at Akron in the east, or at Goldfield, Spokane, and San Diego in the west?

Of course the experience is not lost and if only the workers are wise enough to profit by its lessons it will be worth all its terrible cost to its thousands of victims.

These important events have been rapidly sketched for the reason that just now I am more interested in the future than in the past. The conditions under which the I.W.W. was organized almost a decade ago and which soon afterward disrupted its forces and gave rise to the bitter factional feud and the threatening complications which followed, have undergone such changes that now, unless all the signs of today are misleading, there is a solid economic foundation for the merging of the hitherto conflicting elements into a great industrial organization.

The essential basis of such organization must, as I believe, be the same as it was when the I.W.W. was first launched, and to which the Detroit faction of that body still adheres. This faction is cornerstoned in the true principle of unionism in reference to political action.

In the past the political party of the workers has been disrupted because of disagreement about the labor union and the labor union has been disrupted because of disagreement about the political party. It is that rock upon which we have been wrecked in the past and must steer clear of in the future.

Like causes produce like results. Opponents of political action split the I.W.W. and they will split any union that is not composed wholly of anti-political actionists or in which they are not in a hopeless minority. I say this in no hostile spirit. They are entitled to their opinion the same as the rest of us.

At bottom all anti-political actionists are to all intents anarchists, and anarchists and socialists have never yet pulled together and probably never will.

Now the industrial organization that ignores or rejects political action is as certain to fail as is the political party that ignores or rejects industrial action. Upon the mutually recognized unity and co-operation of the industrial and political powers of the working class will both the union and the party have to be built if real solidarity is to be achieved.

To deny the political equation is to fly – in the face of past experience and invite a repetition of the disruption and disaster which have already wrecked the organized forces of industrialism.

The anti-political unionist and the antiunion Socialist are alike illogical in their reasoning and unscientific in their economics. The one harbors the illusion that the capitalist state can be destroyed and its police powers, court injunctions and gatling guns, in short its political institutions, put out of business by letting politics alone, and the other that the industries can be taken over and operated by the workers without being industrially organized and that the Socialist republic can be created by a majority of votes and by political action alone.

It is beyond question, I think, that an overwhelming majority of industrial unionists favor independent political action and that an overwhelming majority of Socialists favor industrial unionism. Now it seems quite clear to me that these forces can and should be united and brought together in harmonious and effective economic and political co-operation.

There is no essential difference between the Chicago and Detroit factions of the I.W.W. except that relating to political action and if I am right in believing that a majority of the rank and file of the Chicago faction favor political action, then there is no reason why this majority Should not consolidate with the Detroit faction and thus put an end to the division of these forces. This accomplished, a fresh start for industrial unionism would undoubtedly be made, and with competent organizers to go out into the field among the unorganized, the reunited I.W.W. would grow by leaps and bounds.

The rumblings of revolt in the A.F. of L. prove conclusively that the leaven of industrialism is also doing its work in the trade unions. The miners at their recent Indianapolis convention, in their scathing indictment of Gompers and his ossified “executive council,” disclosed their true attitude toward the reactionary and impotent old federation. When Duncan MacDonald declared that Gompers and his official inner circle slaughtered every progressive measure and that the federation under their administration was reactionary to the core and boss-ridden and worse than useless, the indictment was confirmed by a roar of applause.

At the same convention Charles Moyer, president of the Western Federation of Miners, charged that if the strike of the copper miners in Michigan was lost the responsibility would rest upon Gompers and his “executive council.” Gompers, notwithstanding this grave charge, left the convention without waiting to face Moyer. He had to catch a train. He remained long enough, however, to solemnly warn the delegates that the two-cent assessment asked for by the W.F. of M. to support the copper strikers would break up his powerful federation.

Almost eighteen years ago the W.F. of M. withdrew from the A.F. of L. in disgust because the financial support (?) it gave to the Leadville strikers did not amount to enough to cover the postage required to mail the appeal to the local unions. Today, when the W.F. of M. is again fighting for its life, the copper miners are told that a two-cent assessment to keep them and their families from starving would “bust” the Federation.

And this is the mighty American Federation of Labor, boasting a grand army of more than two million organized workers!

What has the A.F. of L., Gompers and his “executive council,” done for the desperately struggling miners of Colorado and Michigan? Practically nothing.

Then why should the miners put up their scanty and hard-earned wages to support Gompers and the A.F. of L.?

The boasted power of this Civic. Federationized, Militia of Christified body of reactionary craft union apostles of the Brotherhood of Capital and Labor turns to ashes always when the test comes, and a two-cent assessment, according to its national president, would kill it stone dead.

The United Mine Workers and the Western Federation of Miners, becoming more and more revolutionary in the desperate fight they are compelled to wage for their existence, are bound to merge soon into one great industrial organization, and the same forces that are driving them together will also drive them out of Gompers’ federation of craft unions. There are other progressive unions in the A.F. of L. that will follow the secession of the miners and augment the forces of revolutionary unionism.

The consolidated miners and the reunited I.W.W. would draw to themselves all the trade unions with industrial tendencies, and thus would the reactionary federation of craft unions be transformed, from both within and without, into a revolutionary industrial organization.

On the political field there is no longer any valid reason why there should be more than one party. I believe that a majority of both the Socialist party and the Socialist Labor party would vote for consolidation, and I hope to see the initiative taken by the rank and file of both at an early day. The unification of the political forces would tend to clear the atmosphere and promote the unification of the forces on the industrial field.

This article is already longer than I intended, but before closing, I want to say that in my opinion, section six of article two ought to be stricken from the Socialist party’s constitution. I have not changed my opinion in regard to sabotage, but I am opposed to restricting free speech under any pretense whatsoever, and quite as decidedly opposed to our party seeking favor in bourgeois eyes by protesting that it does not countenance violence and is not a criminal organization.

I believe our party attitude toward sabotage is right, and this attitude is reflected in its propaganda and need not be enforced by constitutional penalties of expulsion. If there is anything in sabotage we should know it, and free discussion will bring it out; if there is nothing in it we need not fear it, and even if it is lawless and hurtful, we are not called upon to penalize it any more than we are theft or any other crime.

The conditions of today, the tendency and the outlook are all that the most ardent socialists and industrialists could desire, and if all who believe in a united party backed by a united union and a united union backed by a united party, will now put aside the prejudices created by past dissensions, sink all petty differences, strike hands in comradely concord, and get to work in real earnest, we shall soon have the foremost proletarian revolutionary movement in the world.

We need not only a new alignment and a better mutual understanding, but we need above all the real socialist spirit, which expresses itself in boundless enthusiasm, energetic action, and the courage to dare and do all things in the service of the cause. We need to be comrades in all the term implies and to help and cheer and strengthen one another in the daily struggle. If the “love of comrades” is but a barren ideality in the socialist movement, then there is no place for it in the heart of mankind.

I appeal to all socialist comrades and all industrial unionists to join in harmonizing the various elements of the revolutionary movement and in establishing the economic and political solidarity of the workers. If this be done a glorious new era will dawn for the working class in the United States.

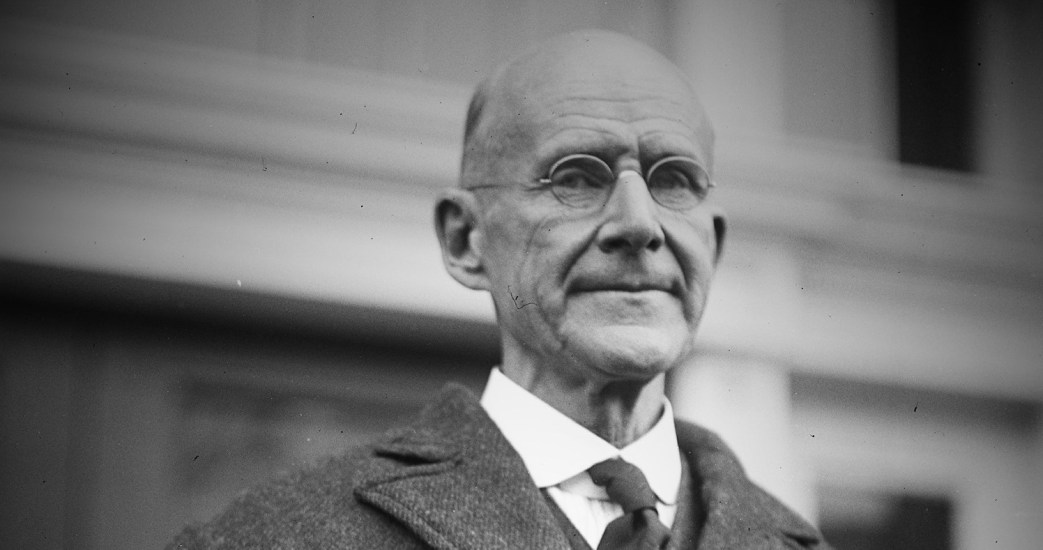

The International Socialist Review (ISR) was published monthly in Chicago from 1900 until 1918 by Charles H. Kerr and critically loyal to the Socialist Party of America. It is one of the essential publications in U.S. left history. During the editorship of A.M. Simons it was largely theoretical and moderate. In 1908, Charles H. Kerr took over as editor with strong influence from Mary E Marcy. The magazine became the foremost proponent of the SP’s left wing growing to tens of thousands of subscribers. It remained revolutionary in outlook and anti-militarist during World War One. It liberally used photographs and images, with news, theory, arts and organizing in its pages. It articles, reports and essays are an invaluable record of the U.S. class struggle and the development of Marxism in the decades before the Soviet experience. It was closed down in government repression in 1918.

PDF of full issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/usa/pubs/isr/v14n09-mar-1914-ISR-riaz-ocr.pdf