Along with Adler and Plekhanov, Daniel De Leon observes Karl Kautsy, Sen Katayama, Rosa Luxemburg, Clara Zetkin, August Bebel, Emile Vandervelde, and Henri van Koll at the Socialist International’s 1904 Amsterdam Congress.

‘Victor Adler and George Plechanoff: Two Pen Pictures’ (1904) by Daniel De Leon from Radical Review. Vol. 2 No. 3. January-March, 1919.

The following two illuminating impressions first saw the light of day as part of a series of essays, officially presented in the unpretentious form of a report of Daniel De Leon, Chairman of the S.L.P. delegation at the Amsterdam Congress, to his party. They were published during the last five months of 1904 in the columns of the Daily People captioned “Flashlights of the Amsterdam Congress,” and, subsequently, issued in booklet form as “Flashlights of the Amsterdam International Socialist Congress, 1904,” by the New York Labor News Co. EDITOR.

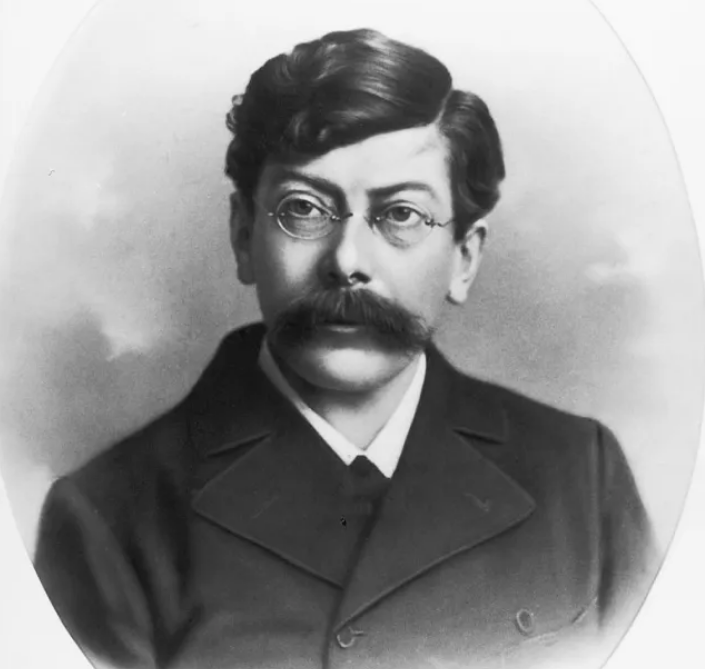

VICTOR ADLER

A strange sensation comes over one when Adler speaks. He is a good speaker; he is an elegant speaker; he arrests the attention of his audience from the start, and keeps it to the finish, untired. One almost wishes to hear more. He spoke repeatedly in the committee. On one occasion he rose to submit a document, and started saying: “I’m not going to speak; only an explanation.” Bebel thereupon called out to him banteringly: “Well, Victor, it must have pained you greatly to make the promise that you would not speak!” I leaned over to Kautsky, who sat just behind me, and asked him whether Adler was so fond of hearing himself talk. Kautsky answered with the neat epigram: “Whoever speaks well likes to speak.” Indeed, Adler speaks well. He spoke often; yet, often tho’ he spoke, he never said a foolish thing. Taken separately, in and by themselves, his sentences were weighed with wisdom.

Nevertheless, taken connectedly, as speeches, in the place where and from the person by whom they were uttered, they were absurd—as absurd as a beautiful fish out of water, or a fine man under water. The finest of fishes is a corpse out of water, and so is the finest of men under water. They are out of the conditions for their existence. In the council of war of Socialism, and in the mouth of the presumptive leader of a revolutionary movement in a great country like Austria, the nice balancing of pros and cons, the scrupulous scanning for possible evil in what seems good, and of possible good in what seems evil, the doubting and pondering—all that sort of thing is strangely out of place, downright absurd, however inestimable it may be in the philosopher’s closet. It savors of the piping thoughts of peace, not of the rough thoughts of war. It savors of contemplative ease, not of action. The law of revolution is motion. Motion implies not necessarily hastiness; contemplation necessarily implies inactivity. As absurd as the revolutionist would be in a seance of philosophers, so absurd is the philosopher in a council of war. The former is a bull in a china-shop, the latter a mill-stone around the neck.

I mean neither to flatter nor insult when I say that Adler is a Montaigne out of season. Montaigne, admittedly the philosopher whose thoughts, more than any other’s, have been absorbed by the thinking portion of the world, had for his emblem a nicely balanced pair of scales, and for motto: “Que scay ie?” (What do I know, after all?). Every time Adler spoke, methought I saw Montaigne’s emblem quivering over his head, with Montaigne’s motto resplendent at its base. Rosa Luxemburg styled Adler’s reasoning “sausage,” what in America would be called “hash.” Plechanoff brilliantly characterized it as the “theory of systematic doubt.” Those who recall the witty, tho’ often somewhat coarse, stories about General Geo. B. McClellan that sprang up during the Civil War, as the result of his Montaigne-like attitude in the field, may form a conception of Adler on the Socialist breastworks. The Adler-Vandervelde proposed resolution fittingly bears Adler’s name as the first. What the Vandervelde contribution thereto meant I shall indicate when I come to Vandervelde himself. The document bore Adler’s stamp in its paralytic contemplativeness.

Though not strictly germane to the subject of Adler, yet neither wholly disconnected therefrom, incidental mention may here be made, as food for thought, that fraught with significance is the circumstance of such a resolution- presented, moreover, after full four years of Jauresist exhibition-being able to muster up such strong support at the Congress as to be defeated only by a tie vote. Nor is this other circumstance lacking of significance in the premises: The International Bureau had declined to recognize the Socialist Labor Party of Australia, whose credentials I carried; it declined the recognition, despite that party’s 25,000 votes; it declined the recognition on the ground that Australia was “a colony and part of the British Empire”; And it decided to postpone action upon the matter until the British delegation’s views were obtained, myself notified thereof, and the matter then taken up anew by the Bureau with fuller light. Now, then, despite all this: despite the credentials of the Australian S.L.P. being laid upon the table on the ground that Australia was “a colony and part of the British Empire,” and as such, prima faciedly not entitled to separate recognition; despite any notification reaching me or action to the contrary being taken by the Bureau; despite all that, the very next day what spectacle was that seen at the Congress?—the “colony and part of the British Empire,” Australia, had a separate seat on the floor with a member of the British delegation, Mr. Claude Thompson, as the lone representative! And he cast the two votes of Australia (every nationality casts two) for, what resolution? For the Adler-Vandervelde resolution! Thus the two votes of Australia, manufactured in that manner, gave the resolution a chance; they came within an ace of triumphantly carrying the resolution over the stile. All comment is unnecessary either as to what had happened behind curtains, or what influences were at work.

Returning to Adler, talented tho’ such a man is, his style of talent tells several tales on the movement that can evolute him to its head. The first of these tales is that the Austrian movement still vacillates on infant legs; the second, that the leader of the Austrian movement is still to appear. When he appears, when the current of the Austrian movement shall have gained steadiness of course, among the first of its acts will be to sweep the vacillating, the philosophic Adler aside. And when that day comes, probably no historian or philosopher will weigh the pros and cons of the removal with a more scrupulously judicial mind than will Victor Adler himself.

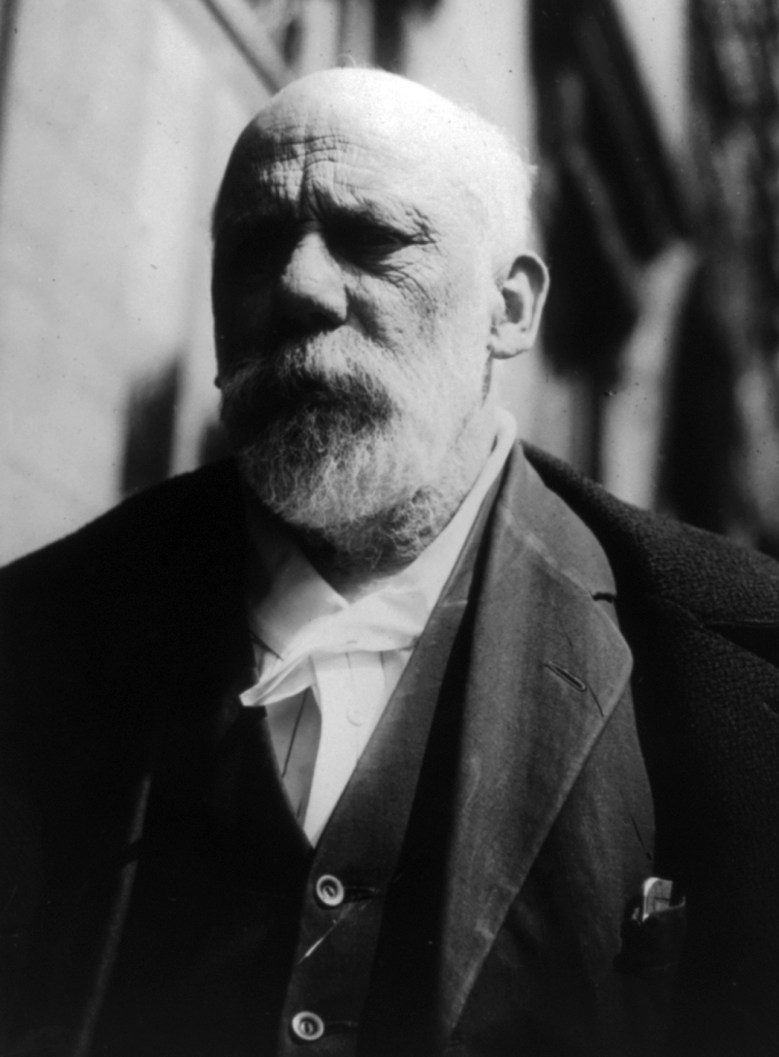

GEORGE PLECHANOFF

In order to safely judge men, their race, their language and the literature of their country should be known. He who is not versed upon these three sources of information will not, unless he be a reckless mind, venture upon a positive estimate. My knowledge of the stock Russian is limited, perhaps still more limited is my knowledge of Russian literature. I can, consequently, have only “impressions” upon the Russian, these impressions being gathered from a general knowledge of their history, the acquaintance and personal contact with a very few of them, and some casual glimpses into the nation’s literature. With this caveat, I may feel free to say I can not reconcile Plechanoff with my “impressions” of the Russian. Heinrich Heine said somewhere that there were two things he could not understand how he and Jesus came to be Jews. I should say that at the Amsterdam Congress one thing forced itself upon me as un-understandable, to wit, how Plechanoff could be a Russian. The man’s quickness of wit and action, aye, even his appearance, are so utterly French that I cannot square them with my impressions of the stock Russian, whom I conceive to be slow in deciding, languorous in action.

Two instances, culled from several minor ones, at Amsterdam, will illustrate the point.

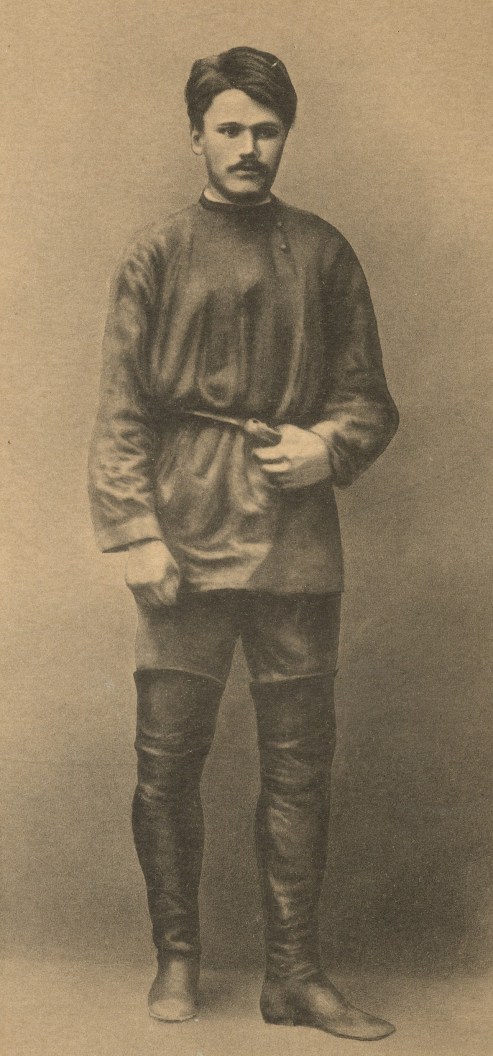

Van Koll of the Holland delegation and chairman of the first day’s session- he was subsequently and wisely made permanent chairman for all the sessions, so as to impart some degree of continuity to them- opened with a speech. Van Koll’s speech sounded as he looks- dull and bovine. His face had no more expression while he spoke than a pitcher of water when the water is flowing out. Indeed, the only time during the whole Congress when I noticed an expression on his face was after he got through reeling off his speech, and Mrs. Clara Zetkin, of the German delegation, was rendering a Ger- man translation thereof. Mrs. Zetkin is the exact opposite of Van Koll. Dull and bovine as he is, she bubbles over with animal spirit. Into whatever she translated, even if it was a simple motion to adjourn, she threw the fire of thrilling, impassioned declamation. Of course she did so in translating Van Koll. A faint glimmer of expression suffused his broad and beefy, though good-natured, face. He looked at the lady sideways, and, no doubt wondering at the “bravoure” that she threw into the translation, looked as if he was thinking to himself: “Did I, really, get off all that?” No wonder he wondered. His speech was of the kind that Paul Singer, of the German Social Democracy, is usually set up to deliver when time and space is to be filled. It was soporific enough to set almost any audience to sleep- let alone so large an audience, about 500 delegates, as the one that he faced, and barely one-third of which could at any one time understand the particular language that happened to be spoken. The Congress was giving distressing signs of listlessness when Plechanoff jumped to the rescue. He sat, as the third vice- chairman, at Van Koll’s left with Katayama, the delegate from Japan, as the second vice-chairman, at Van Koll’s right. Plechanoff had been watching for his chance. The moment it came he seized it. He rose, stretched his right arm across Van Koll’s wide girth and took Katayama’s hand. Katayama took the hint; he also arose and, symbolically, the Russian proletariat was shaking hands with their Japanese fellow wage slaves. It was a well-thought demonstration, the work of a flash of genius. Apart from arousing the Congress from the languor it was drooping into, and driving it to frenzied applause, the handshake of Plechanoff and Katayama at that place was a pathetic rebuke to Capitalism, whose code of practical morality was at the very hour being exemplified in the heaped up corpses of Russians and Japanese on the battlefields of Manchuria. It contrasted the gospel of practical humanity that Socialism is ushering into life, with the gospel of practical rapine that Capitalism apotheosizes.

The second instance of Plechanoff’s quickness of wit and action was one I already have referred to in my preliminary report. It was the assault he made in the committee upon the Adler-Vandervelde resolution, especially the part that attacked Adler. That part of Plechanoff’s speech looked like a succession of flashed tongues of lightning converging upon Adler’s devoted head. It was a succession of French-witted epigrams, lashing what he called Adler’s “doute systematique” (systematic doubt). The strokes went home so unerringly that Adler, phlegmatic though he is, found it necessary to ask the floor for an explanation, when the debate was over, and personal explanations were in order.

Apart from his brilliantly striking personality, Plechanoff’s activity suggests a train of thoughts along a different line. The question takes shape. To what extent can a man in exile effect an overturn in the country that he is exiled from? That Anarcharsis Klootz, the Hollander and exile, played an important part in a foreign country, France, during the French Revolution, is known. And there are more such instances. The question that rises to my mind is not what a role history has in store for a Plechanoff, a Russian exile, this side of the Vistula. The question is, can one, long an exile from his own country, preserve such close touch with it as to become leadingly active in it at a moment’s notice? “Emigrations” during troubled days proverbially became aliens from their own fatherland; when they return home they drop strangers among strange conditions. The instances of Bolivar in South America, Hobbes in England, Castelar in Spain, not to mention royalties without number, who, though long exiled, returned home and led their parties to successful victories, may suggest the answer to the question posed above, were it not for the obvious differences between such uprisings and the social revolution in whose folds Plechanoff is active, and of whose weapons he is one of the titan forgers. In none of those other uprisings did the masses count; in all of them a minority class alone was interested, struck the keynote and furnished the music-with the masses only as deluded camp-followers. It is otherwise with the approaching Social Revolution. It is of the people, if it is anything. Can contact be kept with the people at a distance, any more than it can be kept with a distant atmosphere?

On the other hand, America, the country that many an observer of our times has detected to bear close parallel with Russia in more than one typical respect, remains to all intents and purposes an unknown land to Plechanoff. In a letter from Mrs. Corinne S. Brown, of Chicago- one of the delegates of the Socialist Party at Amsterdam- to the Milwaukee “Social Democratic Herald,” the lady declares that the Congress was a “great revelation” to her, inasmuch as “it was surprising to note of how little importance the United States is among those continentals.” The observation is correct. It includes Plechanoff. Thus, while the unwilling imperial cannon of Japan is signaling for a political revolution in autocratic Russia, while the capitalist system is making giant strides towards transforming the face of the Muscovite’s realm; while here in America Capitalism, having reached its acme, is kicking over one by one the liberal ladders by which it climbed to the topmost rung, and has begun to swing back into absolutism via all the devious paths of popular corruption and political chicanery; while these events, big with results, are both noisily and noiselessly proceeding on their course towards a kissing point, raising Russia ever nearer to the American standard, and lowering America ever nearer to the Russian level- in short, while this evolution is taking place Plechanoff is fatedly, and that unbeknown to himself, becoming more and more an alien in Russia, and at the same time, as to America, he probably has of the country no clearer idea than that it is a quarter from some quarter of which considerable funds flow towards the propaganda that he carries.

Unless untimely death deprive the Revolutionary Movement of Europe of the services of this valiant paladin, the career of George Plechanoff promises to furnish an intensely interesting sociologic specimen to which the historian of the future will turn his eyes for direction, for example and for scrutiny.

The Radical Review was a Marxist theoretical journal published in New York City between 1917 and 1919. Edited by Karl Dannenberg and largely dominated by the perspective and writers of the Socialist Labor Party, it was, however, an independent journal. The Review engaged the Socialist Party and other activists as a vehicle to promote ‘socialist unity’ and ‘ideological clarity’ when the SLP was looking to remain relevant in the the post-War world. With only seven issues produced, the Review hosted several important Marxist thinkers, particularly Harry Waton, international translations, and gave space to long-form articles and serials, and unlike the SLP press, actively engaged its pages in debate.

PDF of whole series (large file): https://books.google.com/books/download/The_Radical_Review.pdf?id=s1feregmhJ8C&output=pdf