‘Economics of a Transition Period’ by N. Lenin from Soviet Russia (New York). Vol. 3 No. 5. July 31, 1920.

At the occasion of the second anniversary of the Soviet power I had proposed to write a short brochure devoted to the study of the problem formulated by this title. But in the pressure of daily work I have up to the present succeeded only in sketching the first draft of certain chapter. I have therefore decided to attempt a brief systematic resume of what I consider to be the essential ideas bearing on the question. Doubtless the systematic character of my resume will involve a number of inconveniences and gaps. Nevertheless perhaps I shall succeed in achieving, as far as a concise statement for a review will allow me, the modest aim which I have put before myself.

Theoretically it is beyond doubt that Capitalism and Communism are separated by a certain period of transition, which must of necessity combine the characteristic traits or properties of these two forms of public economy. This period of transition cannot but be a period of struggle between dying Capitalism and growing Communism, or, in other words, between Capitalism already defeated but not destroyed, and Communism, already born, but still extremely weak. Not only for a Marxist, but also for any educated man, however little acquainted with the theory of evolution, the necessity for a whole historical epoch, recognizable by these general characteristics of a transition period, must be self-evident. And nevertheless all the recriminations relative to the transition to Socialism which we are hearing from the mouths of the contemporary representatives of petty bourgeois democracy (and in spite of their self-assumed Socialist label, all the representatives of the Second Internationale, comprising men like Macdonald and Jean Longuet, Kautsky, and Friedrich Adler, are representative of petit-bourgeois democracy) are characterized by a total ignoring of this self evident truth.

The distinguishing feature of petit-bourgeois democrats is to cherish a disgust for the class struggle, to dream of a means of avoiding that struggle, to seek always to “come to an arrangement,” to conciliate, to round off angles. That is why such democrats either refuse to recognize the whole historical period covering the transition from Capitalism to Communism, or else set before themselves the task of working out plans for the conciliation of the two forces at grips with each other, or of assuming control of the struggle in one of the two camps.

II.

In Russia the dictatorship of the proletariat must necessarily present certain features peculiar to themselves in comparison with the advanced countries, in consequence of the very backward state and the petit bourgeois spirit of our country.

But at bottom we find in Russia the same forces and the same forms of political economy as in any capitalist country whatsoever: in such measure that those features cannot in any way affect the essential points. The forms which are at the root of public economy are capitalism, small production, and Communism. The fundamental forces are the bourgeoisie, the petite bourgeoisie above all, the peasant class, and the proletariat.

The economic activity of Russia in the period of the dictatorship of the proletariat consists in the struggle, during its first stages, of labor, unified on the basis of Communism with a single framework of giant production, against small production, and against the capitalism which has been preserved and which is being born again on its basis.

Labor is unified in Russia on the basis of Communism in such measure as, first of all, private property in the means of production is abolished, and, secondly, the Government of the proletarian state organizes large scale production on a national scale of the state land and in the state enterprises, distributes labor-power amongst the various branches of the economic structure, distributes the accumulated stocks of products for consumption belonging to the state amongst the workers.

We speak of the “first steps” of Communism in Russia (to borrow the expression used by our party program adopted in March, 1919), in view of the fact that all these conditions have been only partially realized by us, or, in other words, in view of the fact that the realization of these conditions is with us only in a primitive stage.

Immediately, in one revolutionary sweep we did all that in the long run could be done in the first days. For example, on the first day of the dictatorship of the proletariat, October 26 (November 8), 1917, private property in land was abolished without indemnification of the great landowners; that is to say, the great landed proprietors were expropriated. In the course of a few months we expropriated, also, without compensation, all the large capitalists, proprietors of factories, workshops, limited liability companies, banks, railways, etc.; the state organization of large production in industry and the transition to “workers’ control,” to “workers’ management,” in factories, workshops, railways, etc., are already realized, while in the sphere of agriculture they are only just begun (Soviet estates, large agricultural enterprises organized by the workers’ state on the state lands). Similarly, the organization of different forms of association amongst the small farmers as a form of transition from small exploitation of the land for profit, to Communist exploitation, is also only as yet taking shape. One might say the same of the organization by the state of the distribution of products instead and in place of private commerce: that is to say, of the preparation and of the transport by the state of the cereals necessary for the towns and of the manufactured products necessary for the country. Farther on will be found the statistical data so far accumulated on this subject.

Small production for profit remains the form of rural economy.

Here we have to deal with a vast and very deep-rooted groundwork of capitalism. On this groundwork capitalism maintains itself and is reborn, fighting against Communism with the most ferocious energy. The weapons of its fight are smuggling and speculation, directed against preparation by the state of stocks and cereals (and also of other products), and, speaking generally, against the distribution of products by the state.

III.

To illustrate these abstract theoretical assertions, let us take some concrete data.

The total quantity of cereals prepared by the state in Russia, according to the figures of the Commissariat for Food, amounted from August 1, 1917, to August 1, 1918, to thirty millions of poods. The following year the amount rose to 110 millions of poods. During the first period of the following year (1919-1920) the stocks prepared amount, it appears, to about forty-five millions of poods, in place of the thirty-seven millions prepared during the same months (August-September) in 1918.

These figures eloquently attest the slow but constant improvement of the situation, from the point of view of the victory of Communism over capitalism. And this improvement has taken place in spite of difficulties unheard of hitherto, consequent upon the civil war, and organized by Russian and foreign capitalists, who had at their disposal the whole forces of the most powerful states in the world.

That is why, in spite of all the lies, in spite of all the calumnies of the bourgeois of all countries, and of all their direct or secret agents (the “Socialists” of the Second Internationale,) it remains beyond dispute that, from the fundamental economic point of view, victory is assured in Russia for the dictatorship of the proletariat: that is to say, for Communism over capitalism. And, if the bourgeoisie of the whole world, consumed with such an excess of rage against Bolshevism, organizes military expeditions, hatches plots against us, it is precisely because it realizes perfectly the permanent nature of our victory in the sphere of economic reconstruction, provided we are not overwhelmed by force of arms — which it does not succeed in achieving.

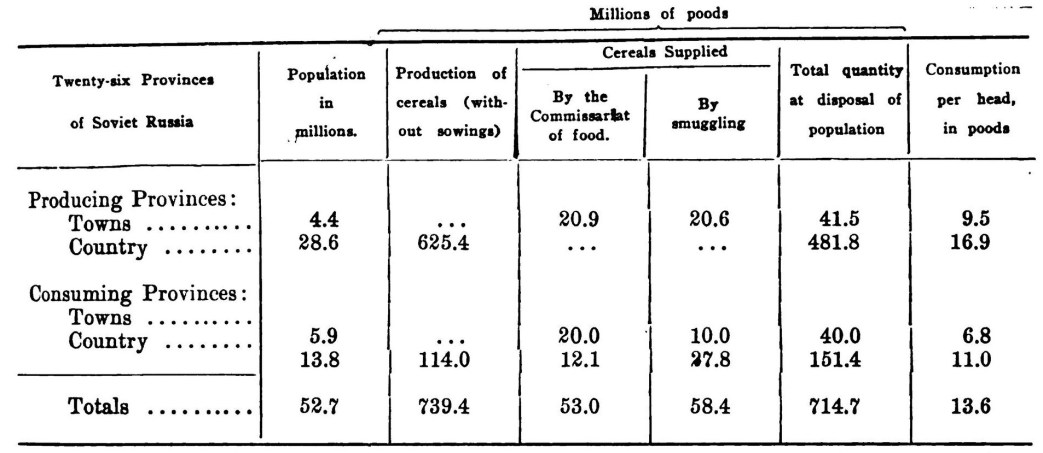

The following statistical material, furnished by the Central Department of Statistics, and which has only just been compiled in order to be given publicity, relates to the production and consumption of cereals, not throughout the whole of Soviet Russia, but only in twenty-six of its provinces (governments). It demonstrates to what degree we have already conquered capitalism during the short space of time which we have had at our disposal, and, in spite of the difficulties unprecedented in the history of the world, amidst which we had to work.

We see that about half the cereals were furnished to the towns by the Commissariat for Food and the other half by smuggling.

An exact inquiry into the feeding of the town workers in 1918 established precisely this proportion. And the bread supplied by the state comes to the workers ten times cheaper than the bread supplied by the speculators. The price of bread fixed by the latter is ten times higher than the price fixed by the state. That is what becomes apparent from an exhaustive study of workers’ budgets.

These are the statistics:

The statistics I have just reproduced, if they are studied as they merit, furnish an exact picture which throws into relief all the essential features of the present economic situation in Russia.

The workers are emancipated from their exploiters, and their age-long oppressors: the great landed proprietors and the capitalists.

This step forward in the path of true liberty and real equality which, in its scope, its extent, and its rapidity, is without precedent in history, is not taken into consideration by the partisans of the bourgeois (including the petit-bourgeois democrats), who understand liberty and equality in a sense of bourgeois parliamentary democracy, which they grandiloquently call “Democracy” in general, or “Pure Democracy” (Kautsky). But the workers have in view real equality, real liberty (emancipation from the yoke of the great landed proprietors and the capitalists); and that is why they come out so firmly for the Soviet power.

In an agricultural country it is the peasants who have gained first of all, who have gained more than anyone, who have reaped the first fruits of the dictatorship of the proletariat.

The peasant suffered from hunger in Russia under the rule of the great landed proprietors and the capitalists. The peasant had never yet had, in the course of the long centuries of our history, the possibility of working for himself; he died of hunger while supplying hundreds of millions of poods of cereals to the capitalists in the towns and abroad. For the first time, under the regime of the dictatorship of the proletariat, the peasant can work for himself, and feed himself better than the town dwellers. For the first time, the peasant has made the acquaintance in practice of liberty; the liberty of eating his own bread, liberation from famine. It is in the redistribution of the land that equality reaches, as is known, its highest point; in the enormous majority of cases, in fact, the peasants have divided the land equally amongst the “consumers.”

Socialism is the suppression of classes. In order to suppress classes, it was necessary first of all to overthrow the power of the great landed proprietors and the capitalists. We have accomplished this part of the task; but that part was not the most difficult. In order to suppress classes it is necessary, secondly, to bring about the disappearance of the differences at present existing between the peasants, and this is a problem which is necessarily more protracted. It is a problem which cannot be solved simply by the overthrow of a class, whatever that class may be.

It is a problem which can only be solved by the organized reconstruction of economic life, by passing from small private, scattered production for profit, to large Communist production. Such a transition is of necessity of very long duration, and would only be retarded and hindered by recourse to hasty and insufficiently considered administrative and legislative measures. It can only be hastened by assisting the peasant in such a way that he is given the possibility of improving, on a vast scale, the whole of the technical side of agriculture, and, indeed, radically to transform it.

To solve this second most difficult part of the problem, the proletariat, after having overcome the bourgeoisie, had speedily to carry out the following line of policy towards the peasant class; it had to wipe out the distinction between the working peasant and the peasant proprietor, the laboring peasant and the trading peasant, the toiling peasant and the speculating peasant.

This difference constitutes the very essence of Socialism. And it is not surprising that the Socialists in words, who are in fact only petit bourgeois democrats (the Martovs, the Chernovs, the Kautskys and Co.) do not understand the essence of Socialism.

This distinction is very difficult, in addition, because in practice all forms of private property, in spite of their differences and their mutual opposition, are confounded in one whole by the peasant. Nevertheless, the distinction is possible, and not only possible, but flows irresistibly from the conditions of rural economy and of peasant life. The working peasant for centuries has been oppressed by the great landed proprietors, the capitalists, the brokers, the speculators, and their states, including the most democratic bourgeois republics. The working peasant has learnt, through his own experience in the course of centuries, to hate and combat these oppressors and exploiters; and this “education,” which life has given him, forced him in Russia to seek an alliance with the worker against the capitalist, against the speculator, against the broker.

But at the same time, the economic conditions under the system of production for profit infallibly transform the peasant (not always, but in the immense majority of cases) into a broker and a speculator himself.

The statistics reproduced above show clearly the difference between the toiling peasant and the speculating peasant.

The peasant who, in 1918-1919, gave to the famished workers of the towns forty million poods of cereals at a price fixed by the state, through the machinery set up by the state, in spite of all the gaps which that machinery reveals — gaps of which the workers’ government is perfectly aware, but which cannot be avoided during the first phase of the transition to Socialism — that peasant is the toiling peasant, the comrade, equal in rights, of the Socialist workman, the best ally of the latter, his true brother in the struggle against the yoke of capital. And the peasant who sold in contraband forty million poods of cereals at a price ten times higher than that fixed by the state, taking advantage of the necessity and of the famine with which the town worker was struggling, thwarting the state, increasing and engendering everywhere lies, theft, chicanery — that peasant is the speculator, the ally of the capitalist, the class-enemy of the worker, the exploiter. The surplus cereals which he possesses indeed were gathered in from the common land with the aid of instruments the manufacture of which entailed the labor not only of the peasants, but also of the workman; and it is perfectly clear that to possess a surplus of cereals and to use part of it to launch into speculation is to become the exploiter of the starving workmen.

You desire “Liberty, Equality, Democracy,” we are told on all sides, and you perpetuate the inequality of the workman and the peasant by your Constitution, by the dispersion of the Constituent Assembly, by the violent requisition of surplus stocks of cereals, etc.

We reply: there has never been a state in the history of the world which has done as much to abolish the de facto inequality, the real absence of liberty, under which the toiling peasant has suffered for centuries.

But we shall never admit equality for the speculating peasant, just as we do not admit “equality” of the exploiter and the exploited, of the well-fed and the hungry, or the “liberty” of the first to plunder the second. And we shall deal with the erudite gentlemen who will not understand this difference as we deal with White Guards, even if these gentlemen give themselves the title of democrats, socialists, internationalists (Kautsky, Chernov, Martov).

IV.

Socialism is the abolition of classes. The dictatorship of the proletariat has done all that it could to achieve that abolition.

But it is impossible to abolish classes at one blow.

And those classes have remained, and will remain, during the period of the proletarian dictatorship; the dictatorship will have played its part when classes disappear, and they cannot disappear without it.

Classes remain, but each of them has changed in aspect during the period of the dictatorship of the proletariat, and the mutual relations of classes amongst themselves have similarly changed. The class-struggle does not disappear with the dictatorship of the proletariat; it only assumes new forms.

The proletariat was, under class capitalism, the oppressed class, the class deprived of all property in the means of production, the class which alone was directly and wholly the antithesis of the bourgeoisie; and that is why it alone was capable of remaining revolutionary to the bitter end.

After overthrowing the bourgeoisie and conquering political power, the proletariat has become the ruling class; it holds the reins of power in the state; it disposes of those means of production which have already been socialized, it directs the hesitating and intermediate elements and classes; it crushes the reviving resistance of the exploiters. These are special problems of the class struggle which the proletariat did not and could not have to face previously.

The class of exploiters, of great landed proprietors and of capitalists, has not disappeared, and it cannot disappear straightway upon the coming of the proletarian dictatorship. The exploiters are defeated but not annihilated. There remains to them an international base, the international capitalism of which they are a branch. They partially retain some of the means of production, they still have money, they still have considerable social influence. The energy of their resistance has increased, just because of their defeat, a hundred and a thousand-fold.

Their “experience” in the spheres of state administration, of the army, of political economy, gives them a very considerable advantage, with the result that their importance is incomparably greater than the numerical proportion they bear to the rest of the population. The class-struggle carried on by the defeated exploiters against the victorious advance guard of the exploited — in other words, against the proletariat — has become infinitely more violent. And it cannot be otherwise, if one is really considering a revolution, and if one does not comprehend under that term (as do all the heroes of the Second Internationale) mere reformist illusions.

Finally, the peasant class, like all the petite bourgeoisie generally, also occupies under the dictatorship of the proletariat a middle, intermediate, position. On the one hand, it represents a very considerable (and, in backward Russia, an enormous) mass of the workers united by the interests, common to all workers, of emancipating themselves from the great landed proprietor and the capitalist; on the other hand, it comprises small farmers, peasant-proprietors and traders. Such an economic situation inevitably provokes a tendency to oscillate between the proletariat and the bourgeoisie. And in the intensified struggle between the latter classes, in the extraordinarily violent subversion of all social relations, when we take into consideration the strength of the habits acquired during the previous epoch of class society — a routine which is particularly noticeable precisely amongst the peasants and the lower middle class generally — it is quite natural that we should witness amongst the latter desertions from one camp to the other; hesitations, waverings, incertitude, etc.

As far as this class, as far as these social elements are concerned, the task of the proletariat consists in guiding them and in struggling for a position of leadership over them. To rally behind it the hesitating and the uncertain: such has had to be the role of the proletariat.

Soviet Russia began in the summer of 1919, published by the Bureau of Information of Soviet Russia and replaced The Weekly Bulletin of the Bureau of Information of Soviet Russia. In lieu of an Embassy the Russian Soviet Government Bureau was the official voice of the Soviets in the US. Soviet Russia was published as the official organ of the RSGB until February 1922 when Soviet Russia became to the official organ of The Friends of Soviet Russia, becoming Soviet Russia Pictorial in 1923. There is no better US-published source for information on the Soviet state at this time, and includes official statements, articles by prominent Bolsheviks, data on the Soviet economy, weekly reports on the wars for survival the Soviets were engaged in, as well as efforts to in the US to lift the blockade and begin trade with the emerging Soviet Union.

PDF of original issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/usa/pubs/srp/v3n05-jul-31-1920-soviet-russia.pdf