A fascinating document for our movement’s history and the debates over the Exclusion Acts that occurred in the labor and left movement and saw the Socialist Party’s right-wing leadership get assailed by the International for their racist, reactionary position against Asian workers. Here, leading wobbly James H. Walsh takes over the editorial page and intervenes with some ‘cold facts’ for workers, urging a position of commonsense proletarian internationalism.

‘Japanese and Chinese Exclusion or Industrial Organization, Which?’ by J. H. Walsh from the Industrial Union Bulletin. Vol. 2 No. 7. April 11, 1908.

The Oriental exclusion question has received so much attention, and caused so much discussion, especially on ‘the Pacific coast, that it is well for us to look for the cause of all this agitation.

So far as is known, the Industrial Workers of the World is the only organization that has ever done any organizing among the Japanese and Chinese in this country. Consequently, a short article from the industrial standpoint of practical experience among these people will be of interest to the readers of THE BULLETIN, as well as educational to a great many so-called American socialists, who claim to be socialists because of a scientific understanding of economics, and yet declare for the exclusion of these people from “our” shores.

Let it be thoroughly understood, to start with, that all this agitation and fight for exclusion of the Orientals is in the “interest of the ‘white’ working men and women,” according to all the agitation of the “Oriental Exclusion League.” composed of a majority of foreigners, who only a short time ago took out their naturalization papers. But do not forget the point to be made in this paragraph, i.e., that all this exclusion fight is in the interest of the “poor working man.” Stick a pin at this point and remember it all the way through.

In fact, there are so many elements now at work (?) to assist the “poor working man” that it will be no surprise if we awake some morning to find that the chains of wage slavery have been unlocked by the master, and the proletariat of the world stands in the midst of the co-operative commonwealth, ushered in by the captains of industry a few days ahead of just when the politician expected to do the same slick trick at the ballot box.

However, let us proceed to the cold facts as to the Japanese exclusion, as that is the question for discussion, and especially is this true when we see men of prominence in the labor movement, who have pledged their word of honor to support the constitution that declares: “No wage earner shall be denied membership because of race, creed or color.” And after swearing to the above, take the platform and advocate exclusion from America to a certain part of the working people of the world, and then conclude the address with: “Workers of the world, unite.”

JAPANESE AND CHINESE ARE PROMPT WITH PAYMENT OF DUES.

In organizing among the Japanese working men, but little difference is found to that among other nationalities, excepting their shrewdness, and honesty to stick with the organization, after having taken the pledge. The first lecture from an industrial working-class standpoint, delivered to them, was before the Japanese Literary Society of Seattle, composed of about six hundred members. This society, of course, is not composed of all working men. It is the Japanese middle class, principally, and it is on this point that the exclusion fight hinges. A few members were secured, and from time to time more were secured, but the old story of lack of finances sufficient to employ a Japanese organizer and place him in the field, is why the work was not carried on successfully.

None of the Japanese or Chinese who become members fail to realize their duty as to paying their dues and keeping in good standing. This cannot be said, truthfully, of all the “whites.” The Japanese and Chinese can be organized as rapidly as any other nationality, and when once pledged to stand with you, no fear or doubt need to be entertained as to them, during labor trouble. But some one will say. Why organize them when we can keep them out of this country? The workers cannot keep them out, because the working class does not compose the organized or dominant part of society. The organized part of society that controls today is the employing class, and it is at their will and desire that exclusion or admittance will be regulated. However, before concluding, I shall grant for argument, that the present agitation will accomplish its purpose and all Orientals will be excluded. This I shall do in order to point out to the worker the proposition that he confronts after the exclusion has been made effective.

EXCLUSION IS IN THE INTEREST OF THE MIDDLE CLASS.

At this point let us see why all this agitation. The greater number of the Orientals that have been coming to this country for some time are small business men. In fact, they are pretty much the “Jew Merchant” of the Orient, and when they enter the business field, their shrewdness, coupled with their keen perception of criminal commercialism, spells ruin to all competitors. The little American cock-roaches sees the handwriting on the wall. I have not the space here to quote the many instances repeatedly published by the capitalist papers as to the closing of a “Jap” restaurant because of its being so filthy, etc., of the “pure food inspector” finding the milk diluted, etc., etc. But the truth of all this is the shifting economic position of the little bourgeois American who secures this persecution in behalf of his own material interest. But the Japanese soon learn this, and then they become equal to the occasion. These people are entering every business of the middle class, and our little American cock-roach merchant sees his finish, unless he can create some disturbance of some kind, and thereby drag the working class into a middle-class fight. This dodge has been worked on the wage slaves many times by the bourgeois, but it remains to be seen whether the dastardly trick can be turned by this dying class in the twentieth century.

Therefore, you can easily see why this agitation is carried on in the “interest of the working man.” Before granting for argument that the Orientals can be excluded, let us deal with the fact that thousands are here, and what to do with them.

COLD FACTS FOR CONSIDERATION BY THE WORKING CLASS.

1. They are here.

2. Thousands of them are wage workers.

3. They have the same commodity to sell as other workers, labor power.

4. They are as anxious as you. to get as much as possible. This is proven by the fact that they have come to this country. For what? To better their condition.

Granting that the above four statements are facts, and no one dare deny them—then what is the problem that confronts us? The Industrial Organization of these people. To say that you cant organize them is a misstatement. We have proven that they can be organized. Had our efforts proven futile among them, then there would be a hook to hang the agitation on for their exclusion. But such is not the case. They can be organized as rapidly, if not more so than any other nationality on earth. We of the Industrial Workers of the World have organized Japanese and Chinese, and the United Mine Workers of America have organized Japanese in the coal fields of Wyoming. This is proof that they can be organized.

When the average worker hears the explanation he is thoroughly convinced that we are confronted with the above mentioned facts, but to think of belonging to an organization that takes in “Japs,” “Chinks,” “Dagoes,” and “N***s” he rebels, until shown that he already belongs to their organization by being a member of the working class of which all the above-mentioned nationalities, are members, and the only escape from being a member of that class is to get into the millionaire class. The working man, however, who is so afraid in falling in “social caste” is generally pretty quick to see the light of identity of interest when his job is at stake, as illustrated by the Sailor’s Union, members of the American Federation of Labor, some months ago.

SAILORS’ UNION ASKS I. W. W. TO KEEP JAPANESE FROM SCABBING.

Of course, the Sailors’ Union refuses to organize the Japanese or Chinese, which is in harmony with the dictates of the A. F. of L. However, the day that the Sailors’ Union members went on strike, a representative called at the I.W.W. hall three times to find the organizer. What was his mission? He said: “We learn that you fellows have organized the Japs?” “Yes, some of them,” we remarked, “but not all of them. They are like the American—slow to see their working class interest.” “Well, what I want is this,” remarked the representative from the water front. “We have got a strike on of the sailors, and we understand that you have organized the Japanese, and that the ship owners are going to employ Japs to take our places, and what we want you to do is to keep the Japs from taking our jobs.”

The organizer proceeded to the water-front with the delegate to see the Steamship Umatilla tied up. On the way from the I.W.W. hall to the docks I said: “Your union, I believe, refuses to organize the Japanese and Chinese.” Of course, this put him in an embarrassing position, and he explained the best that he could. We arrived at the docks to see the smoke rolling out of the large stack, when I said: “Why, I thought you told me the Umatilla was tied up,” and he quickly responded, “Yes, it is.” But I said: “How does it come that the smoke rolls out of that stack? they have got a scab fireman on already, eh?” And quickly came his reply: “Oh, no! You see, the engineer must have a certificate from Uncle Sam, and consequently he can’t quit.” “Oh, I see,” I said, “he does not belong to the union.” “Yes, he belongs to the union,” responded the delegate, “but he must stay at his job or he will lose his certificate from the government.”

JAPANESE STAND TRUE WHILE A. F. OF L. ENGINEERS SCAB.

He then proceeded to tell me what they wanted was to keep the Japanese from scabbing and they could win. I assured him that we would keep off all Japanese and Chinese who belong to the I.W.W., but, of course, that there were hundreds of them who do not belong, and while we can do nothing positive with them, we will use our best efforts to prevent them from scabbing. Then I said: “My friend, if you sailors want to win this strike, you should be willing to do as much on your own part as you are coming to ask of the Japanese and Chinese, through the Industrial Workers of the World,” when he quickly responded: “Yes, we want to win, and we’ll do our part.” How little he realized what he was answering to. How little he realized what was coming. How far he was from knowing the power of the bosses’ union was expressed by the look on his face when I said: “To win this strike is no easy task; we must keep all the Japanese off. This the I.W.W. will do. Now, you pull that scab engineer off and the strike is won, otherwise it is lost.” His organization could not pull the engineer off, but the I.W.W. kept every Japanese member from scabbing, even to the extent that Japanese employment offices posted notices warning the Japanese working men not to take the jobs. For the first time, hundreds of working men along the water-front saw the truth of the teachings of the I.W.W.—the identity of interest of the wage workers of the world.

A FEW WAGE COMPARISONS OF JAPANESE AND “WHITE” WORKERS.

The Japanese possess the quality of “stick” that is necessary in a wage worker to make a good industrialist. At Port Blakely. Where “white” men are driven like Mexican peons in a lumber mill, many Japanese are employed. The Japanese decided to ask for a raise of wages of 20 cents per day. One morning they all rolled up their blankets ready to leave camp if their demands were not granted. The 20 cent raise was granted. This gave the Japanese an average of seven cents per day more than the “white” workman.

At the Tidewater mill, Tacoma, the Japanese and many “whites’ were working for $1.75 per day. The Japanese went on strike for $2 per day. They won. The “whites” hung their heads and held their jobs at $1.75. In a few weeks after the Japanese won, they said: “If we can get the American workers to come with us we can win $2.25 per day.” But the “white” workers were satisfied with $1.75 while the Japanese received $2. Their knowledge of the labor field and how to win is illustrated in the labor report issued by the commissioner of labor of the state of California.

WHAT THE LABOR COMMISSIONER OF CALIFORNIA HAS TO SAY.

He says that the Japanese do not strike, but that they work on, whatever the condition may be, until all idle labor is out of the field, and then, just when the crop is the ripest, when the work must be done, they walk out, making a demand for better wages or shorter hours without any mercy for the employer whatsoever. In other words, they eliminate the scab before they strike.

The labor commissioner of California is quite correct, and it is that very qualification in the Japanese that will make one of the best industrialists ever known. While there are many Japanese working for less than Americans are, there are thousands of Americans working for less than Japanese.

I might cite you too many instances similar to the above, but it is not necessary. A few serve as proof. In the above general review of the Japanese, the same holds true of the Chinese workers also. In many places along the coast, Chinese may be found drawing better wages than the “whites,”‘ and repeatedly in the fish canneries are found Chinese foremen with “white” women and girls working under them. All this complicated mess can only be adjusted by industrial organization and administration.

ARGUMENT GRANTED THAT EXCLUSION CAN BE ACCOMPLISHED.

Let us now argue that through the efforts of the bourgeois and the assistance of the American Federation of Labor, the working class can be dragged into a middle class fight, and are successful in excluding all the Orientals, and sending back those who are here. Granting that such a move can be made, then we must be ready to face the new condition that confronts us.

At this point let us call the attention of the reader to the fact that capitalism is international and recognizes no boundary lines or race distinction. The capitalist has only one thing in view—profits. He does not allow international lines or race prejudice to play any detrimental part to those profits, either, if within his power to prevent the same. He buys “labor power”—the only commodity the wage worker has to sell—in the cheapest market in the world. He buys that commodity the same as he buys any other commodity, and for the same purpose—to be utilized in his factory to return more profits.

Realizing the above economic facts, capital—American as well as Japanese—is seeking investment in manufacturing establishments of the Orient.

INTERESTING STATISTICS BY COMMISSIONER OF LABOR.

A late report of Special Agent W. A. Graham Clark of the department of commerce and labor covers one industry pretty much in detail, and shows the industrial advance in the line of cotton manufacturing. While we have no detailed reports of other industries, the fact remains that their advance is keeping step in the Orient with the cotton factories. Let us quote some figures given out by Mr. Clark of the department of commerce and labor.

Cotton manufacturing, he says, is the most important single industry of modern Japan. Some of the brainiest, most enterprising men of the empire, and American capital, control the factories: the largest banks are heavily interested in the business, and back of the young industries it the whole force of the paternal government urging it on.

There are forty-nine cotton spinning companies in Japan operating eighty-five mills. All of the eighty-five mills make yarn, and fourteen also manufacture cloth. On June 30, 1907, there were, according to the reports of the Japanese Spinners’ Association, 1,450, 949 spindles, of which 1,373.709 were ring and 77,340 mule; also 133,052 twister spindles and 9,136 looms. The capital of these forty-nine companies was $21,966,675; the capital paid in $18,675,479; the reserve fund $6,271,323; the fixed capital (permanent investment) $17,746,271, and the amount of fire insurance carried on buildings and machinery was $15,992,900. The total liabilities of the forty nine companies were $6,598,836.

There were employed 14,369 men at an average wage of 36.17 sen, or 18.08 cents a day, and 61,462 women at an average wage per day of 22.42 sen, or 11.21 cents a day. Figuring this out gives six months’ total wages of operatives as $948,832, or the yearly wages as about $2,000,000.

The mills report a total of $5,370,931 as operating cost of producing 485,577 bales of yarn, and about 71,168,497 yards of cloth. To produce this there was consumed 221,994,790 pounds of cotton.

There was reported a total net profit of $3,980,984 for the first six months of the year; $1,200,014 was charged off to depreciation of buildings and machinery, and after paying about 10 per cent, of an average semi-annual dividend, $940,276 was carried forward.

From these figures it will be noticed that the net profit is entirely above the American proportion to the cost of production. The average worker may say, we care nothing about the profits the capitalist may make in Japan. But this important point must be given consideration from the exclusion point of view. It is this greater profit that lures the American capitalist to invest in the Orient.

With a total cost of $5,370,931 they report a profit of $3,980,984. This is accomplished by men working at an average wage of 18.08 cents per day, and women, of whom there were about four times as many as men, working at an average wage of 11.21 cents a day. Examining the wage account closer shows that the prices paid weavers is about 7 cents per 40 yards, and production is about 50 yards in a day of 12 hours.

LOW WAGES PAID IN JAPAN BUT LIVING IS VERY CHEAP.

The reader should remember, however, that while the wages may appear very small, living is very cheap in Japan. It must be understood also, that the wages in this twentieth century, the world over, means only an existence for the wage slaves, whether in America, Europe or Japan.

The Japanese mills work long hours, and many of them are operated almost continuously. The forty-nine cloth mills average 28.2 days out of 31 per month, and averaged 22 hours to the day, a total of 620 hours as an average for each mill for the month. In the operation of the mills Sunday is not regarded and the mills do not stop for the day. The majority of the mills have two Fridays, the 1st and 15th. In many mills the engine starts at 6 o’clock the morning of the 2d, and runs continuously until 6 o’clock the morning of the 15th; then starts at 6 o’clock of the morning of the 16th and runs continuously until 6 o’clock of the morning of the 1st. This is as near perpetual motion as machines can stand. No stop is made for dinner, the hands taking 30 minutes for dinner in rotation, and a “swing shift” taking the places of those who are eating. Each operative works from 6 to 6 with 30 minutes for dinner, and the night shift comes on at 6 p.m.

There is no child labor law, and some very young children are worked. The mills do not want to work any under 12, as they are not profitable, but in order to get help the factories very often have to take the whole family.

The mills are straining every nerve to develop their export business, and have organized the “Cotton Cloth Export Association,” the object of which is to get control of the foreign trade in the cotton piece goods business, and the mills have agreed to ship 1,000 bales per month, even if they have to sell at a loss in order to compete with America.

Therefore, granting that you exclude them from our shores, they are found creating wealth just across the pond, and this wealth created is in competition in the world’s market.

One other instance will assist in clinching the facts in the above industry. The Union Iron Works of San Francisco laid off many hundred men in the summer of 1907, during commercial prosperity, closing down the shipbuilding industry in that city to a great extent. The Schwab interests which control the above mentioned industry gave out the report that they could not build ships in this country and make any profits. Immediately on this close down we learned of the opening of a great shipbuilding yard at Tokio, Japan. Of course, we all know that the Japanese government will not allow foreign investors to run industries in Japan, but we learn by actual fact that the commercial criminals dodge the laws as easily in Japan as in the United States. Therefore. American capital is investing in the different industries of the Orient.

FAILING TO EXCLUDE, WHAT IS THE PROBLEM BEFORE US?

What is the problem, then, that confronts the worker?

1. The working people, disorganized as they are, cannot force the exclusion of any foreigner from American shores, against the material interest of the employing or capitalist class.

2. If the Japanese be excluded from this country, it will be because of a middle class commercial demand, and the ignorance of the working class will serve only as a dragnet to pull the wage slave, once more, into the cob-webs of middle class interests.

3. Granting that the Japanese are excluded, the American worker still stands in the world’s market to sell his labor power at a price that his employer may manufacture and sell goods at a profit, and compete in the world’s market.

Certainly any worker should see the problem that he is confronted with, and to set up or to continue an agitation of exclusion is only to blur the facts to be dealt with, from the proletarian standpoint. Another point that the American worker has yet to learn is the new competition in the Japanese workmen. In the past the American has found little competition in the European workman in “speeding at the machine.” The European employer has not been able to drive the wage slave at the speed of the machine, as has his American brother employer, and as a result of this drive of the American worker, although his wages have been higher, the American manufacturer has been able to compete in the world’s market because of the greater proportional output. Now comes the Japanese worker—men and women—who can be “speeded” the same as the American, and the race from now on is not a handicap, but a neck and neck race, as is illustrated by the above figures given out by Special Labor Commissioner Clark. The Chinese workers, like the Europeans, can not be “speeded.”

In conclusion, let us say that the Industrial Workers of the World will follow this brief review of the Oriental problem with a pamphlet, as soon as sufficient statistics and data can be secured, to show conclusively that there is only one correct and scientific position to be taken on this question, and that is the Industrial Organization of the wage slaves of the world, regardless of race, creed or color. Understanding this, the speaker may appear before an audience and truthfully and scientifically conclude his address with the words: “Workers of the world, unite” without placing his foot in his mouth.

The Industrial Union Bulletin, and the Industrial Worker were newspapers published by the Industrial Workers of the World (IWW) from 1907 until 1913. First printed in Joliet, Illinois, IUB incorporated The Voice of Labor, the newspaper of the American Labor Union which had joined the IWW, and another IWW affiliate, International Metal Worker.The Trautmann-DeLeon faction issued its weekly from March 1907. Soon after, De Leon would be expelled and Trautmann would continue IUB until March 1909. It was edited by A. S. Edwards. 1909, production moved to Spokane, Washington and became The Industrial Worker, “the voice of revolutionary industrial unionism.”

PDF of issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/usa/pubs/industrialworker/iub/v2n07-apr-11-1908-iub.pdf

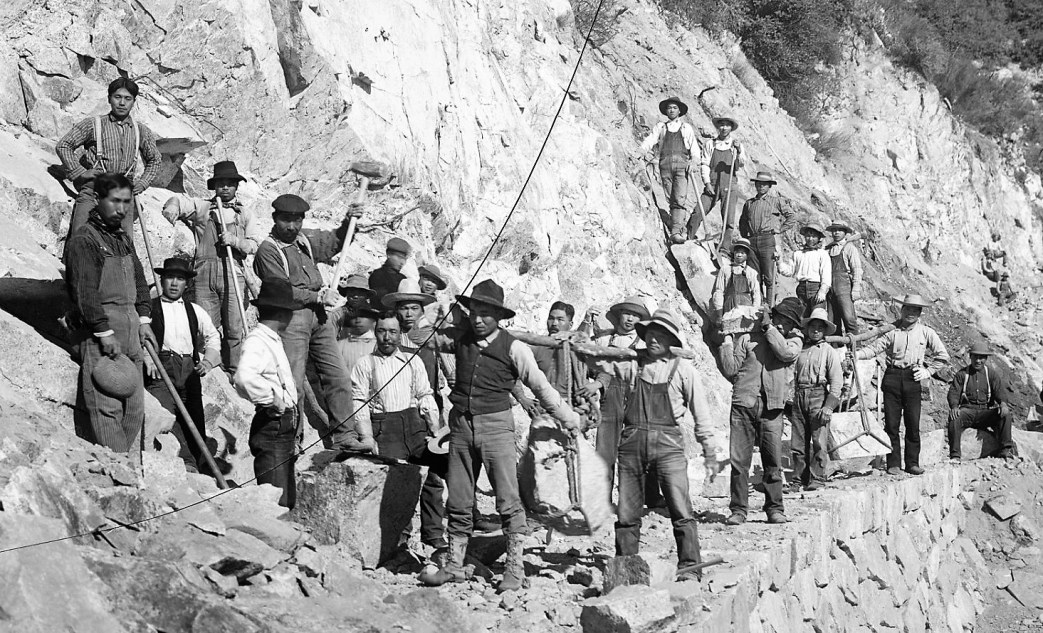

So fun thing with the first photo from Idaho Springs, They’re all Collage Students from The Colorado School of Mines and are studying to become Mining Engineers! It was taken at the Edgar Experimental Mine wich is a classroom mine for the School Of Mines, the man in the middle blinking is Professor James Underhill whom they affectionately called ‘Doc’. A copy of this picture in on display at The Underhill House Museum in Idaho Springs and we have that saw in the basement.

LikeLike