A leader in the Proletcult movement, later director of the Institute of Russian Literature, Pavel Lebedev-Polyanskii richly surveys the new literacy and early publishing efforts of the Soviets as well as the reaction of writers to the Revolution.

‘Literature and Revolution in Russia’ by Pavel Lebedev-Polyanskii from Soviet Russia (New York). Vol. 4 No. 16. April 16, 1921.

When the October revolution broke out in Russia the bourgeoisie of the whole world raised a cry that the Bolsheviks were barbarians, that they would destroy the old culture, the old scientific institutions, publishing houses, schools, etc.

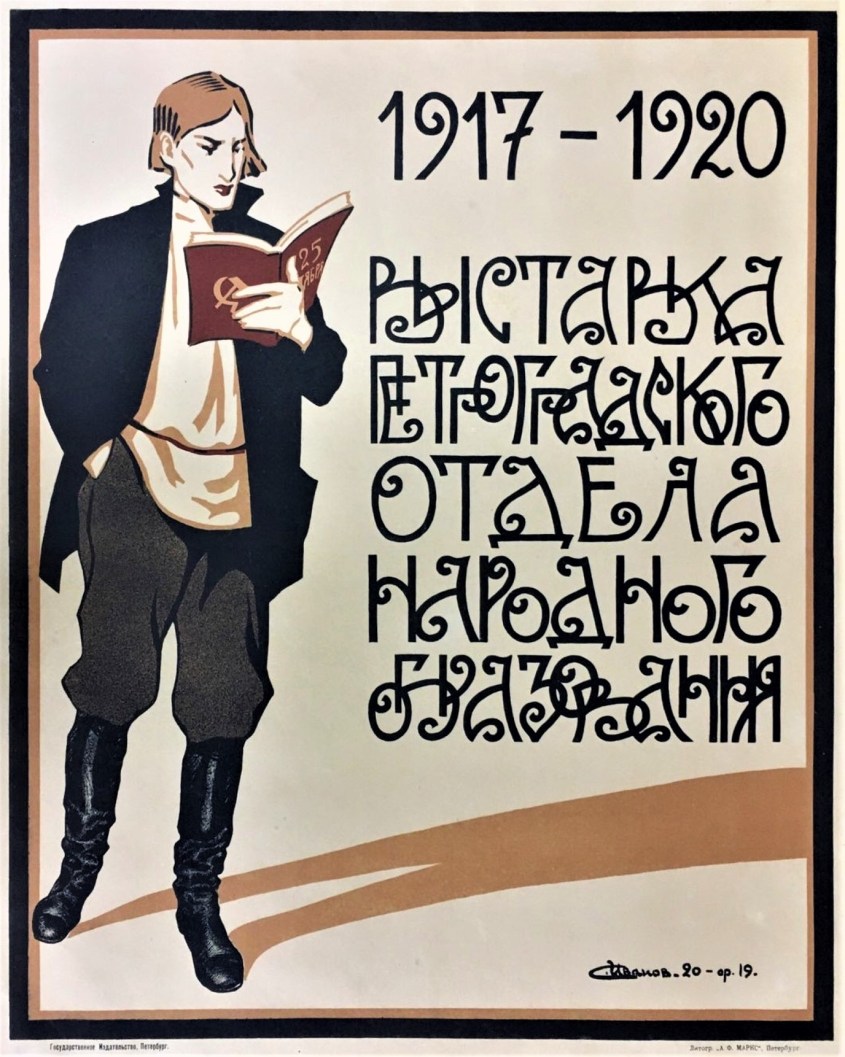

Even a superficial acquaintance with the actual situation of literary work in Russia will show how much conscious lying and class hatred there was in all such assertions. Two or three weeks after the revolution and immediately after the establishment of the People’s Commissariat of Education steps were taken towards the organization of a literature publishing department, which within a very short time, and in spite of all the difficulties due to the civil war, developed very broad activities.

Russia in respect to culture is one of the most backward countries in the world. The masses of the peasantry were kept altogether out of touch with and away from literature. Popular libraries contained only such books as were strictly selected by the Tsar’s censors. They were chosen with a view to strengthening the foundations of reaction, autocracy, orthodoxy, and of nationalism. Many scientific works were prohibited, and almost all books were beyond the reach of the common people because of their price. There were the Zemstvos, it is true, which tried to give the people good books, but they always met with all kinds of obstacles on the part of the authorities. It is natural that under these circumstances the People’s Commissariat of Education was compelled to take upon itself the task of acquainting the people with the literary treasures created by the progressive elements of Russian society in its struggle against the Tsar’s regime.

In this sphere Russian literature has some immortally beautiful works which in respect to art as well as in their burning protest against the oppressive tendencies of the old regime can fire the hearts of men with an enthusiasm for a bright and happy future. Russian literature has always been a chronicle of the miseries and struggles of its preeminent men of the people.

At the end of December, 1917, the Russian Central Executive Committee issued a decree monopolizing all Russian classics, and the People’s Commissariat of Education worked out a plan of its publications. The decree stated: “In the election of works editors should be guided, besides other considerations, by the closeness of connection of the respective books with the interests of the working people for whom they are intended. All issues of such books, complete editions or separate volumes, are to be prefaced by explanatory statements by authoritative critics, historians of literature, etc. For the editing of such popular books a special commission is to be created, composed of representatives of pedagogical, literary and scientific organizations, special experts and delegates of labor organizations. The task of this controlling and editing commission consists in ratifying plans and projects of editions and commentaries presented for its approval by the editors.” Having adopted all measures to make the publications of the Commissariat of Education respond to the spirit of the people while keeping in touch with strict scientific requirements the editing commission was confronted with a third problem, that of low prices. The decree stated: “Popular editions of the classics must be issued at cost and be circulated at low prices and even gratis through libraries serving the labor democracy.” At that time of course there could be no question of issuing new literature. On the one hand the painful conditions of war with German Imperialism and the nascent tremendous struggle against the counter revolution made it impossible to write seriously, to think out and analyse the rapid changes of events. On the other hand those who stood aside from the great struggle of the laboring masses against the bourgeoisie produced nothing, and had they done so, they would not have been able to yield anything except malicious libel and abuse of the Russian proletariat and of the great November revolution.

In order to acquaint the people with the great cultural achievements of the past it was decided to issue the works of Pushkin, Lermontov, Gogol, Tolstoy, Turgenyev, Dostoyevsky, Goncharov, Grigoryevich, Ostrovsky, Uspensky, Zlatovratsky, Resnetnikov, Levitov, Saltykov, Chekhov, Nekrasov, Nikitin, Nadson, Pleshchetyev, Fet, Surikov, Ryleyev, and others. These were poets and novelists, and among other works of the critics of literature the following were issued: Belinsky, Chernishevsky and Hertzen. The publication of the works of Lavrov, Mikhailovsky, Dobrolyubov and Piserev were contemplated. The works of Lavrov, the ideologist of the Social Revolutionists, were given over by request of members of the party to the Social Revolutionist publishing office for scientific preparation, which has already published twenty books out of the fifty he has written.

A literary commission was formed of that group of the Russian men of letters who were not swept away by the then prevalent current of sabotage, i.e., Bryusov, Blok, Verassayev and others became members of the committee. Bryusov was asked to prepare a new edition of Pushkin, Zhukovsky and Nekrassov. An art commission was formed including among others Benoit and Grabar, well known historians of art. As a result of these efforts we now have editions of the works of the above mentioned authors not mutilated by the blue pencil of the merciless Russian censor. To what ridiculous extremes that was carried may be seen in one of Nekraasov’s poems, relating the story of a peasant who had hanged himself. The words of the old editions were “he sat,” whereas the original had been written “he hung.” Instead of “ston” (groan) in one poem was the word “son,” meaning dream. Many parts were entirely eliminated, others rewritten. Now the original has been completely restored, and the Russian people may read the real Nekrassov, the real Pushkin, the real uncensored “Resurrection” of Tolstoy, and many other literary works.

But as the preparation of new editions requires much time and more peaceful conditions of work, a part of the classical literature was reprinted from old plates — the commission of course selecting the best.

All this literature was published during 1918. and the first part of 1919. Every classical author was printed in accordance with the degree of his popularity in editions of from twenty-five to one hundred thousand copies, and was sold at a price of two roubles fifty copecks for a book of 600 pages at a time when bread in the open market was sold at four roubles a pound.

Fiction, Political Science, etc.

Much foreign literature was also published, as for instance Anatole France (**The Gods are Athirst”), Romain Rolland (“Jean Christophe”), Merimee, Walter Scott, Giovanni Olai, Zola (“The Sinners”), Upton Sinclair (“The Jungle”), Voynich and others. Simultaneously with the publishing of fiction steps were taken to offer to the people scientific and popular scientific works. N. Ryazanov began to issue a complete edition of Plekhanov’s works under the general heading of “Library of Scientific Socialism.” Among other works of the collection were published some of Bebel’s books and many of Kautsky’s works written when the latter was a revolutionary Marxist; a full collection of Marx’s and Engels’ works was started, of which several parts have already been published. Two large volumes of Bogdanov’s and Stepanov’s Course of Political Economy were also published, as well as a History of Russia by Pokrovsky in five volumes, and an almost complete edition of the works of the well known Russian historian, Kluchevsky. Many books on the history of the Russian revolutionary movement and of the revolutions in Western Europe were also published, among them the works of Jaures, Aulard, Bloss, Louis Blanc, Heritier, and others.

At present several series of popular scientific books are being issued. This work is carried on in collaboration with the following authors: Professor Timiryazev (Botany), Madame Tmiryazev (Physics), Walden (Chemistry), Wolf (Mineralogy), Mikhailov and Blashkov (Astronomy), Berg (Geography), and others.

In this series were republished some of the admirable works of the botanist, Timiryazev, “Charles Darwin and His Teaching,” the famous “Life of Plants,” etc. Some more of his books and pamphlets are ready for publication.

Under the general title “Theory and Practice of a Uniform Industrial School” there appeared the pedagogical works of noted Western European and American pedagogues, in order to give an opportunity to the pedagogical world of breaking away and emancipating itself from the prejudices of the past, and becoming acquainted with the situation of advanced pedagogical ideas. In these groups were included the works of Seidel (Zurich), Kerschensteiner (Munich), Gurditte (Munich), Gerlich (Bremen), Hansberg (Bremen), Perrier (Geneva), Hall (America), Findly (Manchester), Beadley (London), Montessori (Rome), Schultz and Ruble (Germany). To these works should be added contemporary Russian works on the Industrial school by the Russians, Blonsky and Levitin.

Besides the publishing organization of the People’s Commissariat of Education, there existed that of the All-Russian Central Executive Committee of Soviets, which mainly published propagandist and political literature, and of the Central Committee of the Russian Communist Party, which published exclusively scientific Marxist literature.

In the spring of 1919 these three publishing enterprises were united in the State Publishing Offices.

By this time the revolution had deeply permeated our immense Russia, presenting colossal demands for propagandist literature, leaflets, posters, and other material. Naturally owing to these conditions and also because of the scarcity of paper, the publication of classical authors was shifted to a secondary place. But pamphlets were published in two hundred thousand copies each, and such necessary books as the “ABC of Communism,” by Bukharin and Preobrazhensky (a book of 340 pages), was published in a million and a half copies.

The National Publishing House

By this time there began to appear the publications of other People’s Commissariats. Many books, pamphlets, leaflets and posters were published by the People’s Commissariat of Agriculture and People’s Commissariat for Military Affairs.

At the present time the State Publishing Offices have so widely developed their activities that their work can only be judged by catalogues and the “Book Bulletin” published by the Central Book Chamber. From books on swine breeding and horse shoeing to scientific modem works and Utopias of social life thirty to fifty years hence — all have been included in the range of work of the State Publishing Offices.

Its publications have a large circulation from five thousand to hundreds of thousands of copies according to the respective subjects and the reader for whom they are intended. Technical scientific books are published in five thousand copies, scientific ones in ten thousand, popular books in fifty to hundred thousand and more. But even with such a circulation Soviet Russia experiences a lack of books, and for a private individual it is most difficult to obtain these. We have now about fifty thousand libraries, and to every one of them the Central Printing Offices (the distributive organ) has to present one copy or more of each publication according to the library and the book in question. And how many more books ought to be distributed among the army and out of the way places where printed works have not yet penetrated in sufficient quantities. (Petrograd branch of the State Publishing Offices, according to its report up to January 1, 1921, has published altogether 1,107 books amounting to a total of 49.649,600 copies of fiction, 18 magazines, in 1,435,000 copies and 20 miscellaneous books, in 417,000 copies. The Moscow branch baa published a no less number and variety.)

Only now with the termination of the war, when we can set to work to reorganize our paper industry and re-establish the efficiency of our printing offices, and when our comrades have the possibility of doing literary work, shall we be able to satisfy this great need of ours to its full extent. And our people so revere books and so thirst for them.

Three committees have been created and are at work: (1) For the investigation of the imperialistic war, (2) for the history of the Communist Party, and (3) for the history of the Russian Revolution. And in the future we shall know much of the truth that has as yet remained concealed from us.

Proletarian Books and Papers

Having enumerated, as far as space permitted, the different publications and specified their numbers, we should like to call the attention of our readers to another side of the question, namely, to the work done by the working class — especially to the proletariat and to the writers it has produced.

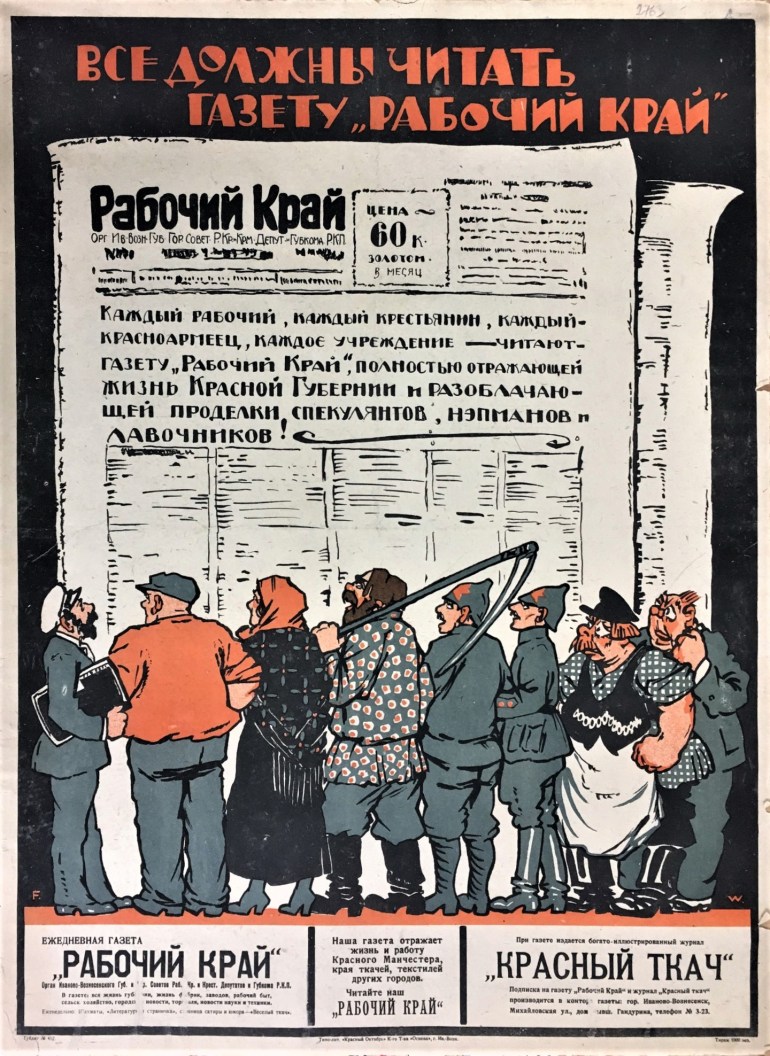

It goes without saying that the revolution has not been able to bring forward worker-scholars, and that it is not scientific work we shall have to deal with. The worker of Western Europe gains some stray crumb of knowledge — just enough to enable him to manage his machine and do his work — but the Russian proletariat has lived outside the pale of enlightenment and only a few individuals — party workers, have been heretofore enabled to obtain connected information, and that almost exclusively in the domain of politics. Now all — in a greater or lesser means — participate in the Soviet papers published in almost every town. The entire paper, sometimes without any help on the part of the committee and intellectuals, is conducted by them alone — leading article and news, feuilleton and literary department. In many places the papers are conducted entirely by the new fresh elements born of the storm and stren of our proletarian revolution.

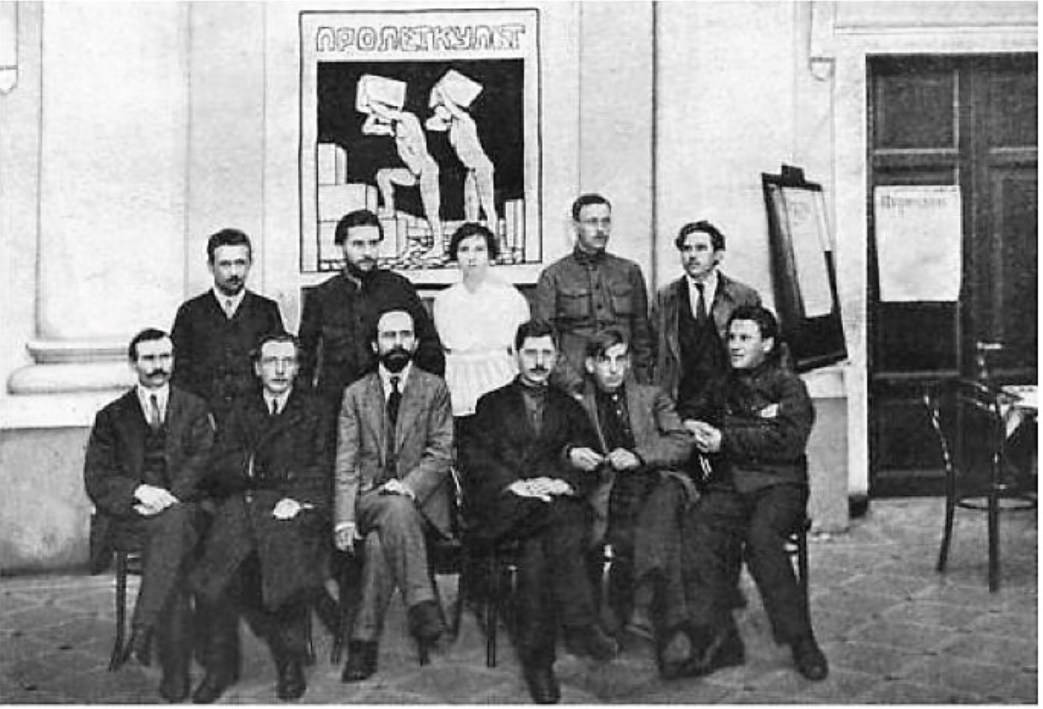

On the other hand the worker sections have done some considerable work in the sphere of fiction and poetry. With the aid of “Proletcult” (Proletarian Culture) and independently of it a number of proletarian writers have arisen, among whom must be mentioned: Caster, author of a collection of poems and stories entitled The Poetry of the Laborer’s Effort”; Bessalko, author of the novels “Unconsciously,” ‘The Catastrophe,” and the stories “Ufe,” “The Childhood of Kouska,” of the “Stone Cutter,” a drama; Samotitnik, “Under the Red Flag”; Sadoffiev, “Dynamic Verses”; Pomorsy, “Flowers of Revolt”; Kirilov, “The Dawn of the Future”; Berdnicov, Arski, Tikhomirov, Kaj, Tarasov, Omtsoli, Kusnetzov, Gerasimov, Alexandrovsky, Lokhtin, Malashkin, Stepnoi, Belotzerkovsky, KKasin, Rodov, Filipchenko, Kotomki, Eroshin, Loginov, and several others.

Poets of Town and Country

The peasantry has also produced poets from its midst: Oryeshin, Klonev, Yessenin, Klitcbkov — men of great talent, and several secondary poets. There exist editions of Poets of the People named after Nikitin and Surikov, the peasant poets.

An ideological struggle is waging between the proletarian and peasant poets. The former are striving to depict the communistic outlook, while the latter are still cherishing the old petty bourgeois ideology, although of course somewhat revolutionized.

Before the November revolution the poets wrote principally of the hardships of life and exploitation, cursing their slavery, dreaming of the struggle for a happy future; sometimes their dreams were of the country and of the smug bourgeois ideal. Reflecting the ideas of their own class the worker poets revealed not so much their own communistic ideal but the ideas of a democratic-revolutionary outburst; but after the November revolution their poetry from being purely revolutionary changed into revolutionary communistic poetry.

The worker no longer curses the town as a vampire that sucks his blood. The town is a great bridge to the triumph and emancipation of man-— a gigantic forge where a new and happy life is forged. In the town the worker poet sees the dawn of a new and superbly beautiful era. The factory is no longer a place of exploitation. In the factory “every man has become an enthusiastic poet of the sounds of the forge and harp strings; a titan with strong wings, a titan of the dawning future.”

Labor does not kill the thought and feeling of the worker. No, on the contrary it will vanquish everything and create new laws. The machine is no longer a tool of subordination, its din and noise are songs, a mighty call to life, sunshine and struggle, and the poet-worker identifies himself and merges with his machine. “We are made of iron,” says the proletarian poet.

Without abandoning its militant propagandist features, full of the certainty of its triumph, the thought of the worker is beginning to bring forth ideas of the creation of a new life, to realize the power of the proletarian collectivity, to draw deeply for its themes, giving them a social philosophical tendency, in order to organize more thoroughly and firmly the feelings and thoughts of the proletariat in its victorious path towards the communistic ideal.

The peasant poets are still singing of their fathers, but not as dumb slaves cursing life, but as free eagles. They still love to sing of peasant life and nature, but among them too the thought is banning to take root of transforming the tilling of the soil, and new ideas are forming of changes in their mode of life, relations among men and general outlook.

And lastly we should like to speak of our new reader. In former times only “intellectuals” were to be seen about book shops or with books in hand, and only rarely, very rarely, a worker or provincial happening to be in town. Now, however, every delegate from the provinces to the Soviet Congress or any other gathering, unfailingly will be seen rummaging among shops and stores in search of literature. He obtains permits and vouchers, abuses red-tape, if he does not get enough and finally, laden with books, takes up his seat in the railway car tranquillized, with the idea that you can get the books you want in the end, even if it is a hard job. He gets books on agriculture, horticulture, glancing with a sigh at the scientific books and muttering to himself, “Cursed bourgeois, it is your fault that I don’t understand what is written here.” He keeps guard over his books, keeping a look out on the luggage shelf, afraid that some one should take his treasure by mistake. After carefully perusing the pamphlet on the breeding of cattle, he turns over the pages of the “Communist International,” fearing to soil them, and remarks, turning to his neighbor, “What a head that Lenin has.”

Laboring Russia is reading, thinking, and building up a new life — re-measuring, comparing, and loving the book — its friend.

There was a time when Nekrassov asked in his famous poem: “Will the time ever come when our peasants will buy on the market not the foolish stories about Blucher and Milord, but the works of Bielinsky and Gogol?”

Yes, we have crossed the bar. The people are buying and reading the “Communist International.”

Soviet Russia began in the summer of 1919, published by the Bureau of Information of Soviet Russia and replaced The Weekly Bulletin of the Bureau of Information of Soviet Russia. In lieu of an Embassy the Russian Soviet Government Bureau was the official voice of the Soviets in the US. Soviet Russia was published as the official organ of the RSGB until February 1922 when Soviet Russia became to the official organ of The Friends of Soviet Russia, becoming Soviet Russia Pictorial in 1923. There is no better US-published source for information on the Soviet state at this time, and includes official statements, articles by prominent Bolsheviks, data on the Soviet economy, weekly reports on the wars for survival the Soviets were engaged in, as well as efforts to in the US to lift the blockade and begin trade with the emerging Soviet Union.

PDF of full issue: (large file): https://www.marxists.org/history/usa/pubs/srp/v3n09-aug-28-1920-soviet-russia.pdf