While work in distribution centers has absolutely increased, it is certainly not new. Neither, apparently, are the working conditions and employee handling manuals of the companies engaged, as this article details. With too many parallels to Amazon to list, this gem of an essay on the massive Chicago distribution of Sears Roebuck paints a picture immediately recognizable today. How far we have come, comrades.

‘A Study in Distribution: Sears, Roebuck & Company’ by Phillips Russell from the International Socialist Review. Vol. 12 No. 7. January, 1912.

WE Socialists have a good deal to say about production. We can give figures and facts pertaining to the subject at a rate which frequently reduces an argufying enemy to silence. But what about distribution? Have we not rather neglected the study of this important branch of modern industry in our keenness to inform ourselves on the more prominent science of production?

It must be kept in mind that some day it is going to be up to the working class to take over the industries—the factories, the big workshops, the mines, the railroads, the great stores, etc.—and operate them for ourselves. Consequently we must be prepared. We must know as well as possible beforehand exactly what we are going to be called upon to do and how to do it. When in doubt, see how the big capitalist does it. It is to his interest to bring out the greatest amount of efficiency with the least expenditure of effort. One of the groups of capitalists that are pointing the way to efficiency in distribution is the firm of Sears, Roebuck & Co., of Chicago, that bugaboo of the little merchant and petty business man.

Sears, Roebuck & Co. are the biggest and best known mail-order retail distributers in the United States, if not in the whole world. They have made their name known wherever the postal service can carry a catalogue, and that bulky volume, weighing two or three pounds and carrying the price and description of everything from a paper of pins to a furnished house, has made its insinuating way at some time or other into perhaps every community of the United States. Sears, Roebuck & Co. will handle your order for a buttonhook with the same facility and ease as for an automobile and they will send you the same grateful acknowledgment by post card.

They are also manufacturers on a large scale, but most of the energy and attention of their 9,000 employes is given to distribution.

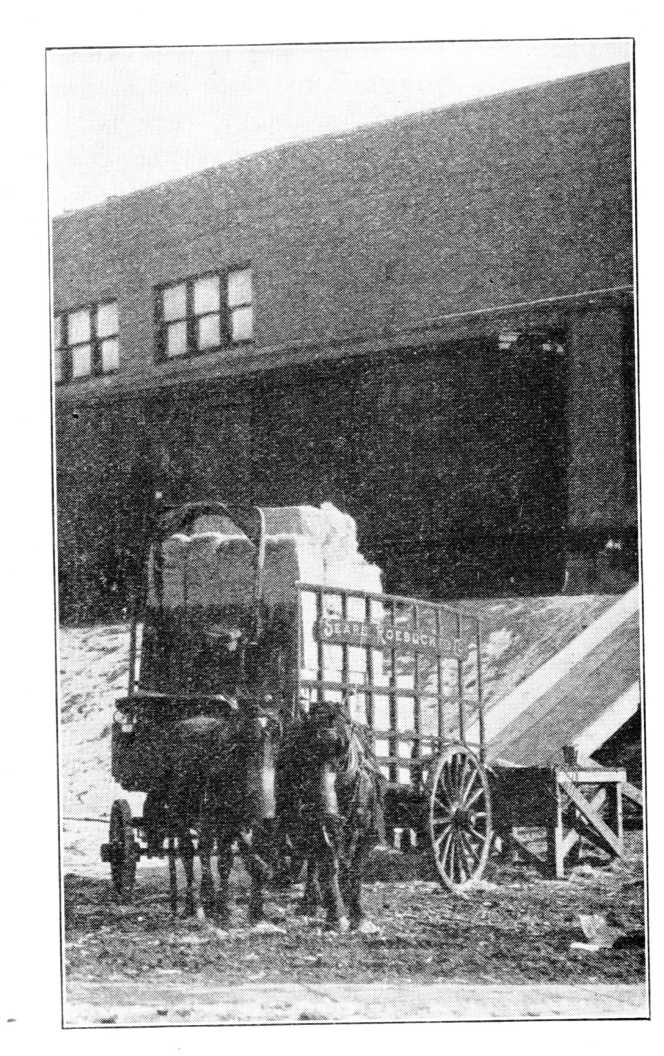

Sears, Roebuck & Co. do a business of more than $60,000,000 a year and at times their sales amount to as high as $250,000 in one day. From 45 to 65 carloads of freight alone are daily hauled away from their doors.

Yearly their business grows and daily their sales climb higher and higher. Steadily they are making it harder and harder for the keeper of the general store at Cross Corners, as well as the small merchant of Kankakee, to make a living. This is the day of Things on a Big Scale and it is up to the little man either to get in line or get out. For instance, only the other day the newspapers chronicled the. fact that Marshall Field & Co., the great department store distributers of Chicago, had just bought the controlling interest in several of the biggest textile mills of North Carolina. What chance will the little retailer now have against Marshall Field & Co. in dealing in these textiles? No wonder that statistics kept by the commercial agencies show that only 5 per cent of the persons who start a business eventually succeed!

In other words, 95 out of every 100 men who in these days put all their money, brains and energy into the founding of a new concern are foredoomed to failure! They can’t succeed. The cards are stacked against them.

Now, Sears, Roebuck & Co. belong to the 5 per cent that have won. Hence it is worth our while to discover the reasons why, to learn how they do things, to discover upon what basis they have achieved their supremacy.

Sears, Roebuck & Co. occupy a group of big buildings situated on several acres of ground on the west side of Chicago—where land is cheaper than in the business center of the city and where workers can be had in abundance. These buildings are, in effect, merely huge warehouses where products are stored until called for.

By inspecting the Sears, Roebuck plant we can get a very good idea of what the distributing centers of the new society will be like in the coming era in which production will be for use, not for profit making, and in which distribution will be carried out for the comfort and convenience of all, not for the enrichment of the few who at present control it.

It is a commonplace to describe a great store or factory as a beehive. The Sears, Roebuck plant really resembles one very closely. Each floor is partitioned off into so many rooms or cells, rising tier upon tier, These cells are divided into so many groups, each group being a department devoted to the handling of one particular product.

For instance, there is the clothing department. In one cell are great tables piled high with overcoats. Six hundred overcoats shipped make a fair day’s business In another cell are endless racks of ready-to-wear suits. Ina third is a regiment of tailors busy making these suits. They cut up one bolt of cloth at a time, do you think? Not by a considerable sight. From 50 to 100 layers of cloth are spread upon a giant table at one time and an electric machine cuts out the different parts of 50 to 100 garments at once like a hot knife through a pad of butter.

One group of workers does the basting, another does the sewing, a third puts in the lining and so on. Fifty men can do the work of 300 by the old way. Less and less labor power is wrapped up in a suit of clothes every year. That’s the reason you and I can get a hand-me-down for $9.75 that looks almost like the merchant tailor’s $25 suit and wears just about as long.

Suppose Sears, Roebuck & Co. receive an order for one of these suits from James P. Jones, of Jonestown, Ark. The order is duly recorded by one of a thousand clerks and a requisition is sent to the ready-made clothing cell. Here a young man—there are very few old ones with Sears, Roebuck —this young man selects the proper suit from the huge stock and deposits it in a basket. A boy seizes this basket. Does he walk down seven flights of stairs and tell the people there to send it off -to James Jones? He does not. He drops the basket into a chute and down it shoots into the wrapping department, where another young man seizes it, places it in a neat pasteboard box and turns it over to a third young man who swiftly wraps it up. Another boy comes along and dumps the package into a chute again. Down it drops into the shipping department, sliding out on the floor, where one of a line of men reads the tag it bears. If it is to go by express, he shoves it over to one side; if by freight, to another side. Again it is seized and properly addressed and labeled. If it is an express package, down it drops again into the express office—every company in the United States has an office in the Sears, Roebuck main building—whence it is immediately dispatched.

Perhaps James’ suit is part of a regular family order, comprising, say, a mantel clock, a family Bible, a horse bridle, three suits of flannel underwear, a bottle of perfume, a case of canned oysters, a driving buggy, a woman’s hat, a churn, a pair of baby’s shoes, a coal stove, a half dozen shirtwaists and a carpenter’s saw—to give a few items frequently received in one order. In that case all the articles are packed into one box when possible and sent by freight. This is the sort of ‘order that will make half a dozen of the small dealers in Jonestown gnash their teeth when they hear about it. It makes them realize their helplessness.

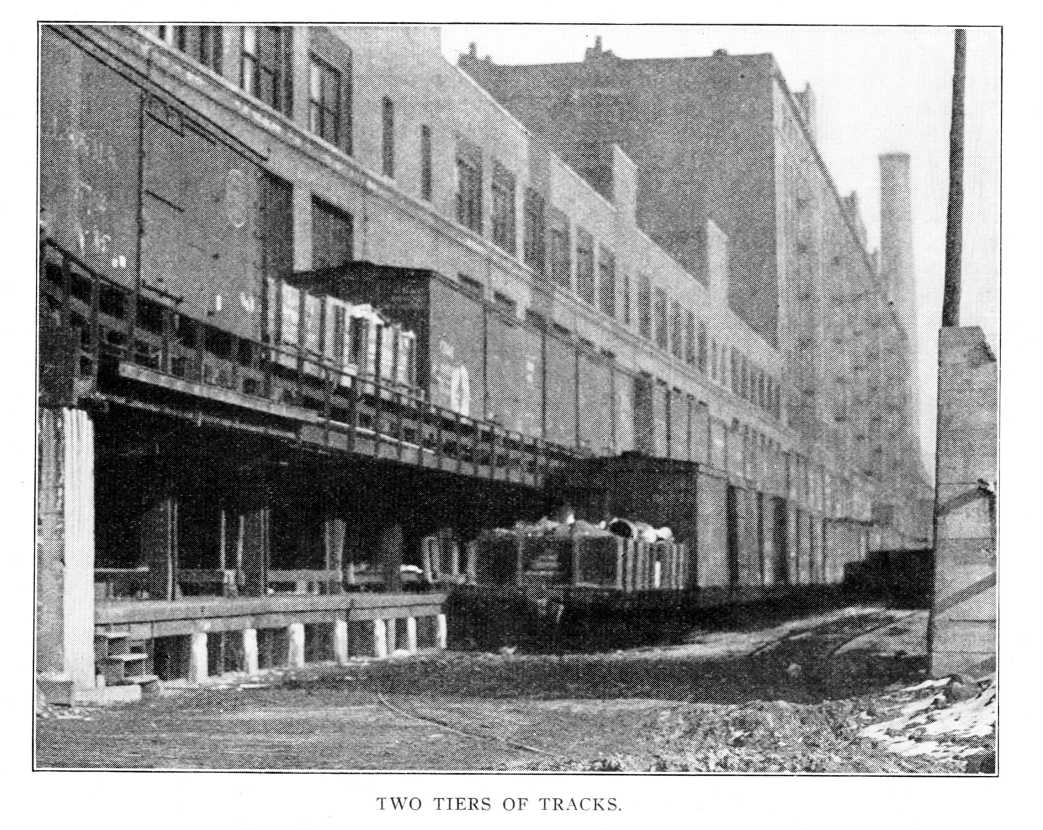

Now, when this box for Jonestown is ready to go out, it is not put on a wagon and hauled to a distant railway depot. The furthest it travels before being loaded into a freight car is about 50 feet. Six railroad tracks run right under the big shed of the main building and the freight cars are backed clear up to the doors of the Sears, Roebuck shipping department.

That is the way Sears, Roebuck & Co. achieved “success”; that is, made money as distributers—they use as little labor power as possible. They employ no human labor where a mechanical device will do as well. They permit no employe to take 50 steps where five steps can be made to do. Their plant is virtually a great machine, and it works almost automatically. Just enough workers are employed as will keep the machine running properly. There are 9,000 employes at present. If we applied the Supreme Court or “unscrambling eggs” process to the Sears, Roebuck plant and compelled it to split up into small and competing shops, we would probably find, say, 5,000 good-sized stores on our hands, employing about ten persons each. In short, 9,000 people are doing work that would have required 50,000 not many years. ago. That is the same as saying that 41,000 persons have lost their jobs—forced out of employment by the machine process.

Not only do Sears, Roebuck & Co. employ as little human labor as possible, but they pay for it at lowest rates. That is because most of the labor they need in their business is unskilled, and unskilled labor is always plentiful and therefore cheap. It requires no high degree of training or intelligence to copy off an order, to arrange a row of packages on a shelf or to pack a goods box, and work of that nature is about all that is required of most Sears, Roebuck’s employes.

Pick up the Chicago papers and you will always find standing advertisements from Sears, Roebuck & Co. in the “help wanted” columns. The concern is always shorthanded, principally because comparatively few workers can endure the high speed and the low wages. As soon as they acquire a little experience they go elsewhere.

I once met a man on a train out of Chicago who told me that his sister stayed nine years with Sears, Roebuck & Co., and when she left she was being paid $7 a week.

Sears, Roebuck & Co. have built up a great fortune, then, out of the merciless exploitation of their workers. Not that the latter are ill treated. On the contrary, the firm is most “benevolent” to its employes. It has provided restaurants where workers can obtain meals at a few cents. There are rest rooms for the women and girls and athletic grounds for the men and boys. There is even a beautiful little park, with a lake, gold fish and so on, for tired employes. And, oh, yes—on a corner of the Sears, Roebuck grounds is a Y. M. C. A. building. The firm gave the land for it, also $25,000 towards its erection. The big capitalists discovered some years ago that the Y. M. C. A. is a good thing for the soothing and amusement of their slaves.

Has Big Biz a reason for encouraging the Y. M. C. A.? You bet it has!

Sears, Roebuck & Co. put their money into the Y. M. C. A., into restaurants for their employes, and other “welfare work,” for the same reason they put it into any other investment—because they expect it to pay. Take the matter of cheap restaurants, for instance. Why do big employers go to ‘such pains to furnish low-priced meals to their employes? Let us see.

A big corporation pays a girl worker, say, $4 a week. It provides for her and her sister workers a restaurant in which a fairly wholesome lunch can be obtained’ for eight cents, or 50 cents a week. But suppose this girl had to go outside for her lunches and was forced to pay 20 cents each for them, or $1.20 a week. In that case the firm eventually would have to raise her pay 70 cents a week, or the difference between 50 cents and $1.20.

So with all the “philanthropy” of employers. When analyzed it is always found to be a cold-blooded business proposition.

Here, then, are 9,000 workers toiling faithfully away, nine and ten hours a day, distributing the things that other workers have produced.

And over both armies of producers and distributers stand their employers, doing absolutely nothing, but absorbing the wealth as fast as their slaves pile it up.

Could a crazier scheme of things ever have been invented? Could anything be more wretchedly farcical than the capitalist system under which we live?

Some day the workers in the Sears, Roebuck and similar plants will quit being slaves. All together they will organize and unite with the producers and then goodbye to Sears, Roebuck & Co. and their class. They will have to go to work.

The International Socialist Review (ISR) was published monthly in Chicago from 1900 until 1918 by Charles H. Kerr and critically loyal to the Socialist Party of America. It is one of the essential publications in U.S. left history. During the editorship of A.M. Simons it was largely theoretical and moderate. In 1908, Charles H. Kerr took over as editor with strong influence from Mary E Marcy. The magazine became the foremost proponent of the SP’s left wing growing to tens of thousands of subscribers. It remained revolutionary in outlook and anti-militarist during World War One. It liberally used photographs and images, with news, theory, arts and organizing in its pages. It articles, reports and essays are an invaluable record of the U.S. class struggle and the development of Marxism in the decades before the Soviet experience. It was closed down in government repression in 1918.

PDF of full issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/usa/pubs/isr/v12n07-jan-1912-ISR-riaz-ocr.pdf