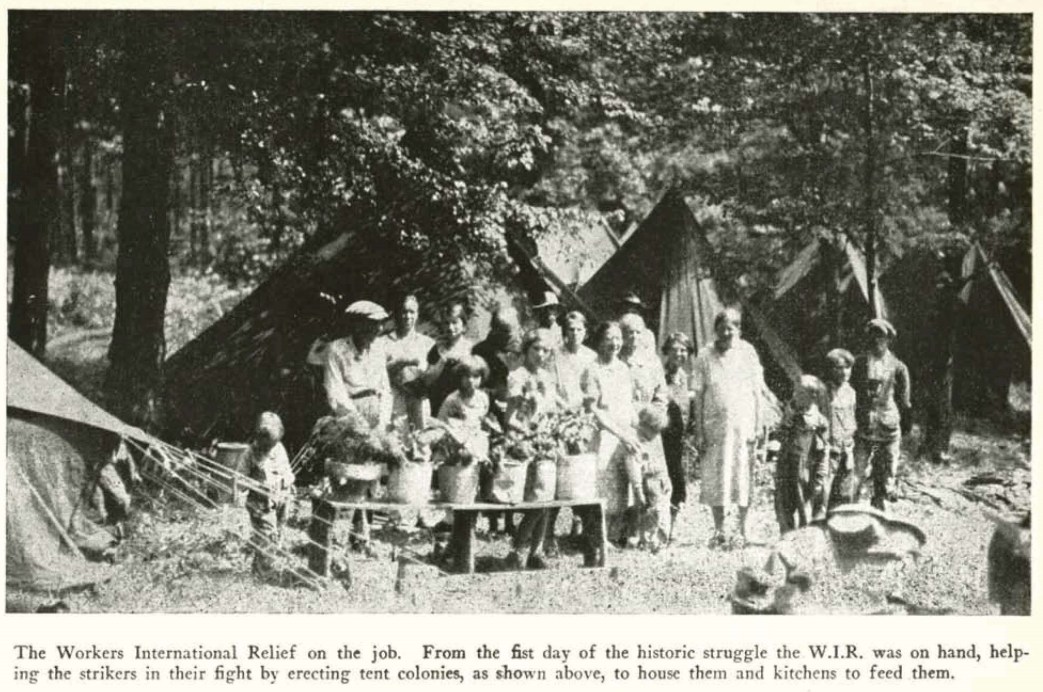

While unique in its particulars, in many ways the 1929 Communist-inspired textile strike in Gastonia, North Carolina was a harbinger of the C.I.O. unionization drive of later 1930s as it reached into previously unorganized territory and workers. The first substantial strike of the new ‘Third Period’ T.U.U.L. unions, the National Textile Workers Union led the struggle with the Workers International Relief setting up a tent colony, and the International Labor Defense providing legal support. An intense and dramatic struggle, death, jail, exile, and death penalty trials followed with Communist Party activists, notably women, playing central roles. William F. Dunne writes on the beginnings of ‘a beginning.’

‘Gastonia: A Beginning’ by William F. Dunne from New Masses. Vol. 5 No. 2. June, 1929.

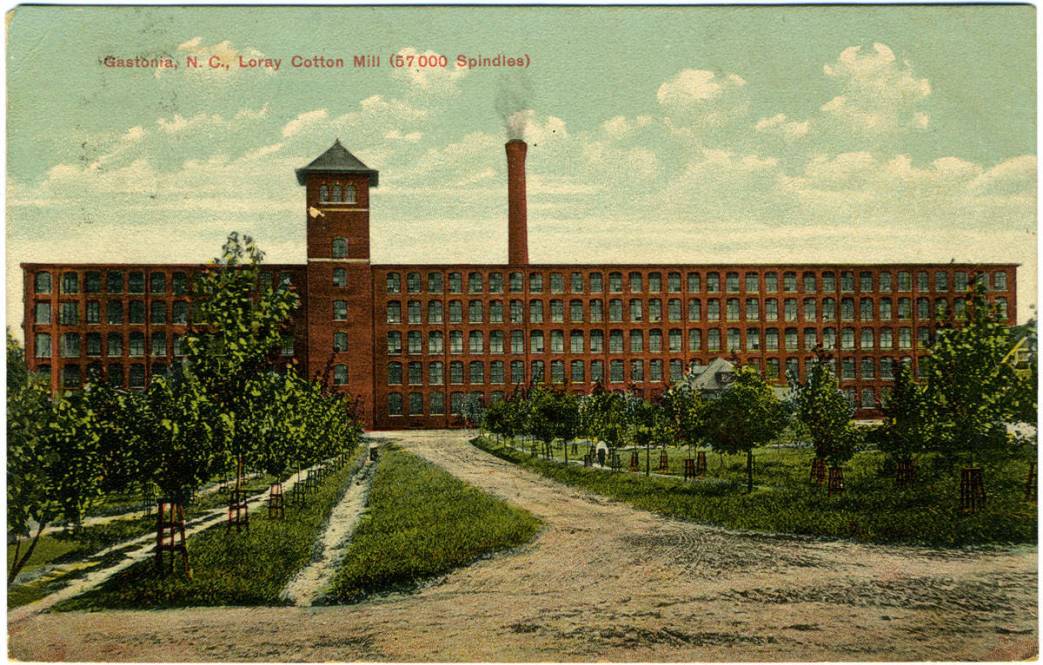

Gastonia is to the textile industry of the south what Pittsburgh and Gary are to the steel industry, Centralia and Everett to the lumber industry, Butte to the metal mining industry.

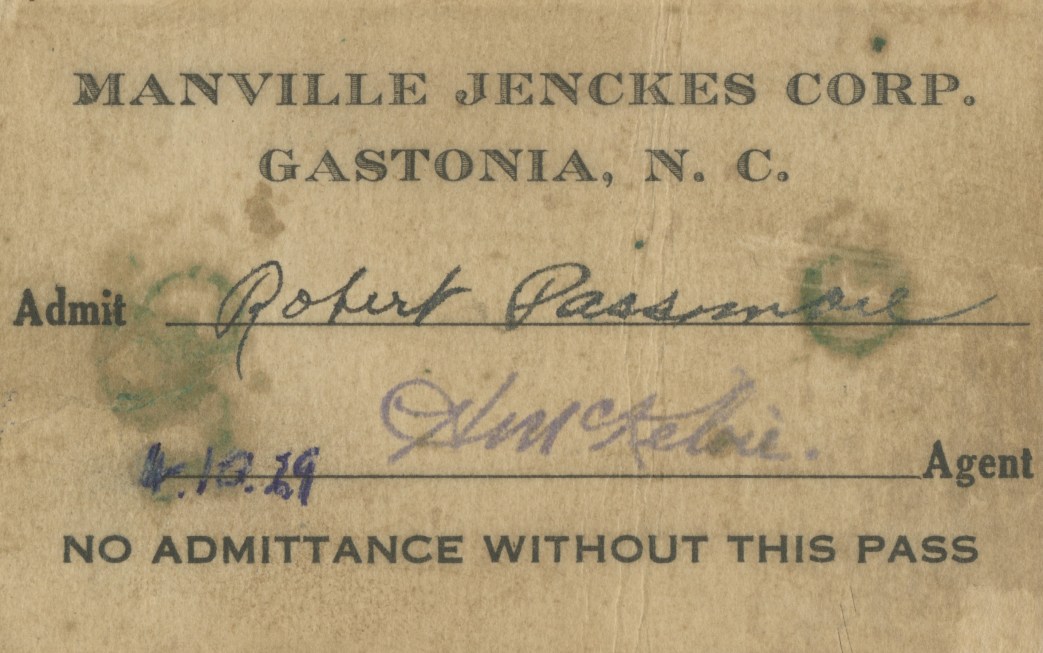

Under the domination of the Manville-Jenckes company Gastonia has come to symbolize the economic and political hegemony of the textile barons in the south— particularly in state of North Carolina. Gastonia is a “company union.” The city and county officials are as much a part of the machinery of the Manville Jenckes company as are their looms and spindles. The middle class has no independent existence. Merchants, doctors, lawyers, teachers, preachers worship at the shrine of Manville-Jenckes. They are the most ardent defenders of the company and its whole system of robbery and oppression down to its last detail.

The shibboleths of the old south have been refurbished and adjusted to the service of the new ruling class — the textile capitalists who have replaced or are rapidly replacing the old landed aristocracy. Southern patriotism, god, heaven, home, fundamentalism and the fireside, white supremacy — these old catch words are worked overtime in behalf of the new exploiters whose policy and deeds duplicate in many respects the horrors of the early English factory system.

Economic domination expresses itself in complete control of the political machinery in Gaston county. Those fair-minded persons who chatter about the majesty of the law and the necessity for reverence for and obedience to it, should live for a while in Gaston county.

If one carries out the commands of the Manville-Jenckes company and its agents, if one accepts the wages and working conditions the company imposes and makes no complaint, if one takes no issue with the flood of obscene company propaganda poured out on the community through the columns of the Gastonia Gazette , through the Rotary, Kiwanis and Lions clubs — in all of which Major A. L. Bulwinkle, chief counsel and agent- provocateur-in-chief for Manville-Jenckes is the high cockalorum — if one simply works and absorbs enough nourishment to work again and says nothing, one is a law-abiding and loyal American.

The National Textile Workers Union profaned the shrine. It led a strike in the Loray mill — the holy of holies. Thousands and thousands of dollars have been spent by Manville-Jenckes in preserving this inner temple of the cotton textile industry. To the southern textile barons the Loray mill represented the goal for which they all strive — a slave-pen impregnable to assault by union organizers, where no worker dared breathe discontent.

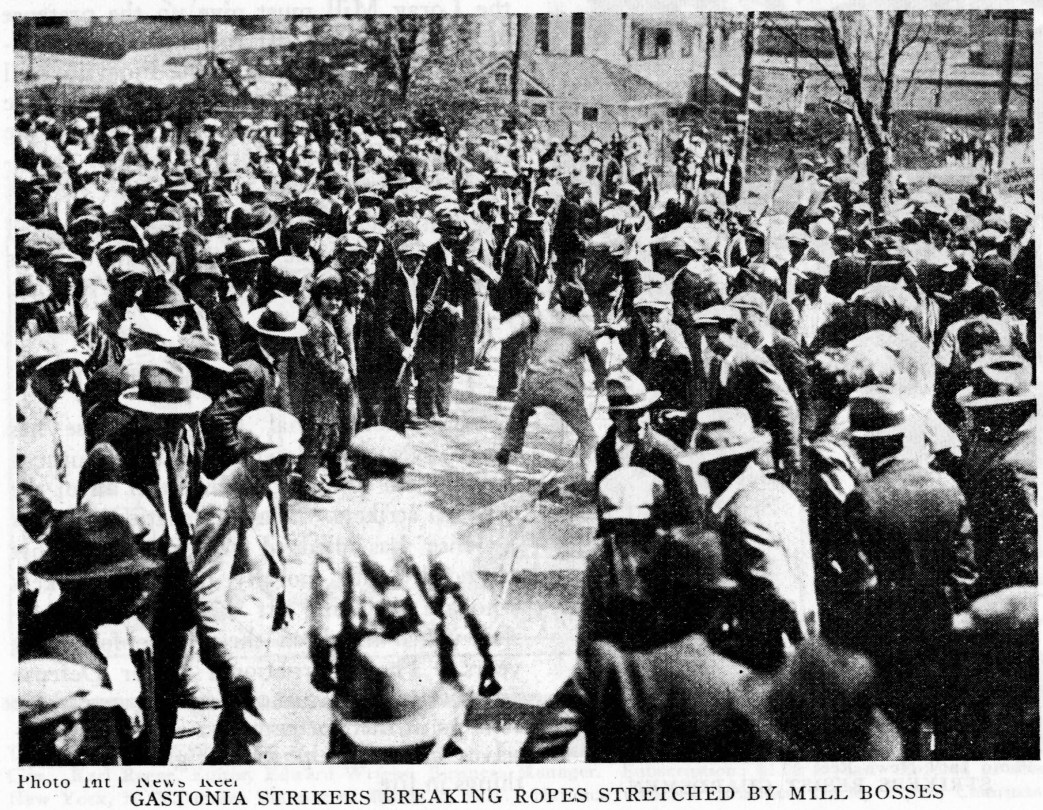

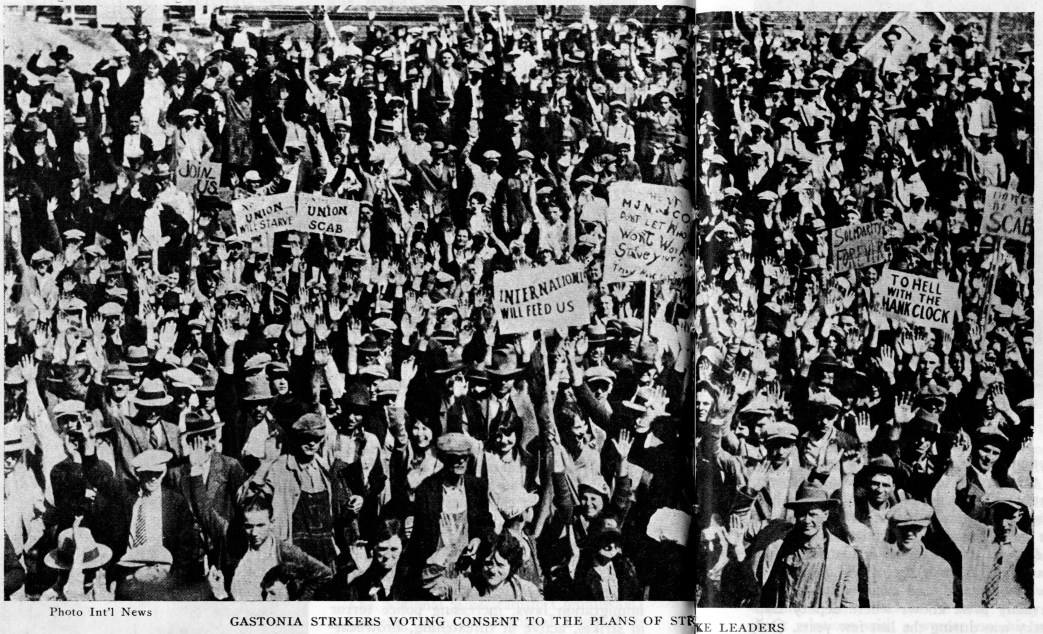

The strike with its mass picketing, its well-organized relief and its systematic education of the strikers in the fundamentals of the class struggle, its mobilization of the women, the youthful workers and the children into disciplined battalions, the appearance of the Communist Party as a force in the textile industry — all this in the stronghold of the textile barons aroused a sadistic fury expressing itself in a reign of terror that has had few precedents in any country.

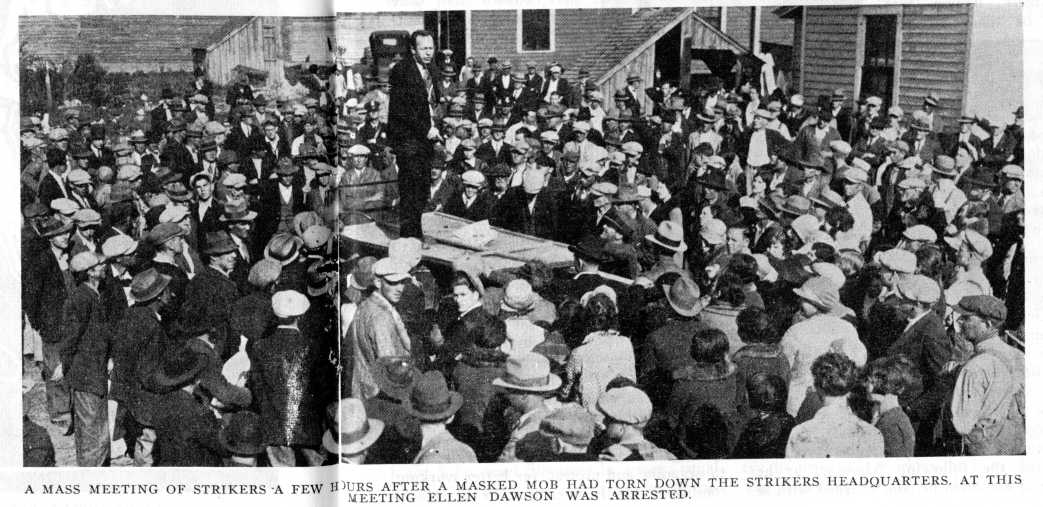

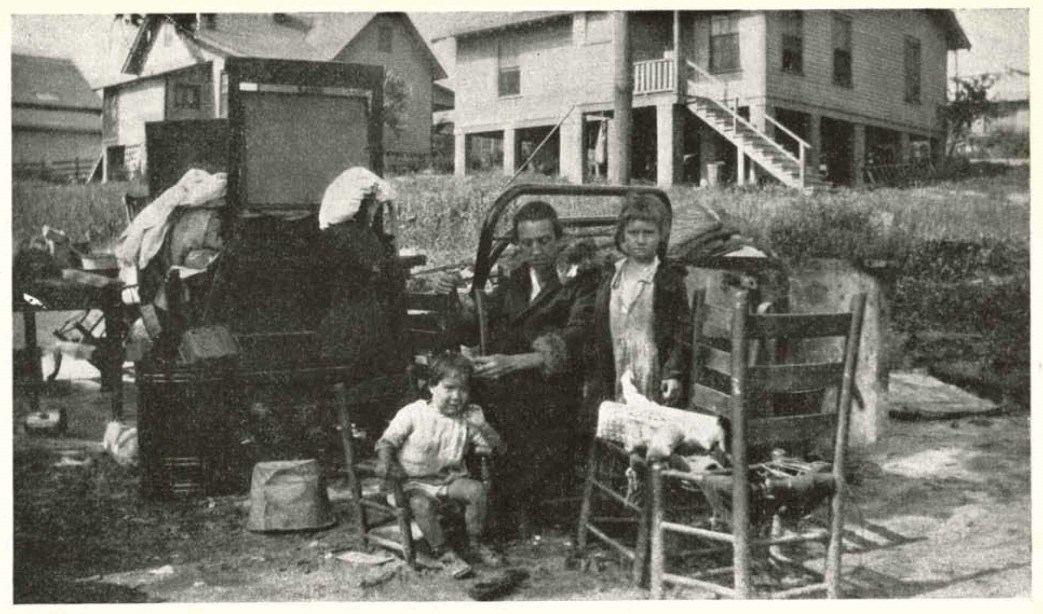

Troops were called in, the strikers’ hall and the Workers International Relief headquarters were destroyed — provisions defiled and thrown into the street — by a masked mob after the police had obligingly arrested and disarmed the workers guarding the hall.

Some vacant property was rented, the relief headquarters housed in tents and a new union hall and office established.

The troops were withdrawn and the task of intimidating, beating and jailing strikers and sympathizers — men and women — placed in the hands of the regular police forces and special deputies.

As in other company towns, the Manville-Jenckes corporation has any one it wants sworn in as a special deputy. It has organized under the command of Major Bulwinkle its “Committee of One Hundred” — a band of company hangers-on and payroll patriots with a sprinkling of professional thugs and gunmen. Beatings and arrests made by the regular police forces and this fascist gang were regular daily occurrences.

The N.T.W. members organized a guard for their headquarters to prevent a repetition of the raid on and the destruction of their hall. The strike was not called off and the strikers who went back to work did so with the knowledge that another strike had to come — and to prepare for it. Large numbers of porkers were blacklisted and they and their families were — and are still supported by the W.I.R.

2. STRIKE!

On June 5 plans were completed for another walkout from the Loray mill. The workers inside had arranged for a picket line of strikers to march past the mill. This was to be the signal for the walkout, set for the afternoon of June 7. The company spies had learned of this plan. Inside the mill they were busy trying to terrorize the workers. The “Committee of One Hundred” was armed and in readiness. The police forces were ordered to be on hand to give a legal color to what the company intended to be an orgy of brutality in which there would undoubtedly have been many deaths of strikers and organizers. The instructions were to get Fred Beal, southern organizer for the N.T.W. at all costs.

At the meeting which was held at the union headquarters before the picket line started eggs and rocks were thrown at Beal by company agents. One of them raised his gun to fire at Beal but a striker grabbed his arm and the bullet went into the ground.

The picket line was met by police and deputies at what is called the Airline railway tracks. There one of the deputies knocked a grayhaired woman down and told her he would “shoot her brains out.” The old lady got up, stretched out her arms and told him: “Go ahead and shoot, you yellow cur, I’m ready to die.” The police clubbed indiscriminately. They choked Vera Bush and dragged Sophie Melvin by the hair. The picket line turned back and one striker started to walk home down the railway track. Two deputies knocked him down. As he lay with his back across a rail one of them jumped up and down on his stomach. The other said: “Go ahead, let’s kill the son-of-a-.” The deputies were heard to say: “Come on let’s go to the tents and kill them all.”

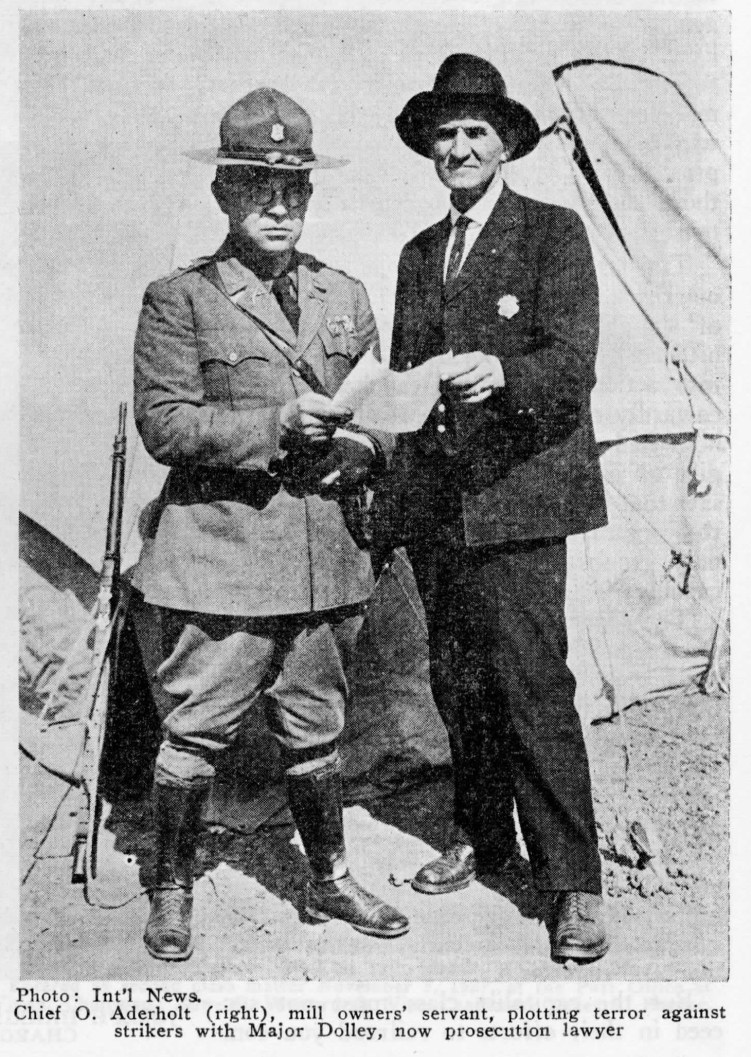

Most of the strikers returned to the union and relief headquarters. Then came Police Chief Aderholt with four officers. They jumped out of their car and as they advanced on to the union property one of the strikers challenged them and asked them if they had a warrant. One of them replied: “We don’t need any god-damned warrant. We got all the warrant we need.” Three of the officers seized the guard, knocked or threw him to the ground and began to beat him with revolver butts and kick him — to “stomp” him as they say in Gastonia. One of the other strikers, standing near the union building, called to the police: “Turn him loose! Turn him loose!” One of the officers turned and fired at him. The general shooting in which Aderholt was fatally shot, and four other officers and Joseph Harrison, a union organizer, wounded, followed.

The “Committee of One Hundred” led by Bulwinkle came soon afterwards, raided the headquarters, broke into and searched workers homes all night long, beat strikers and dragged them to jail. Patrols were placed on all roads. No one was allowed to leave or enter Gastonia. The records of the N.T.W. were seized. The city proper and the mill district became a hunting ground in which workers were pursued like wild animals.

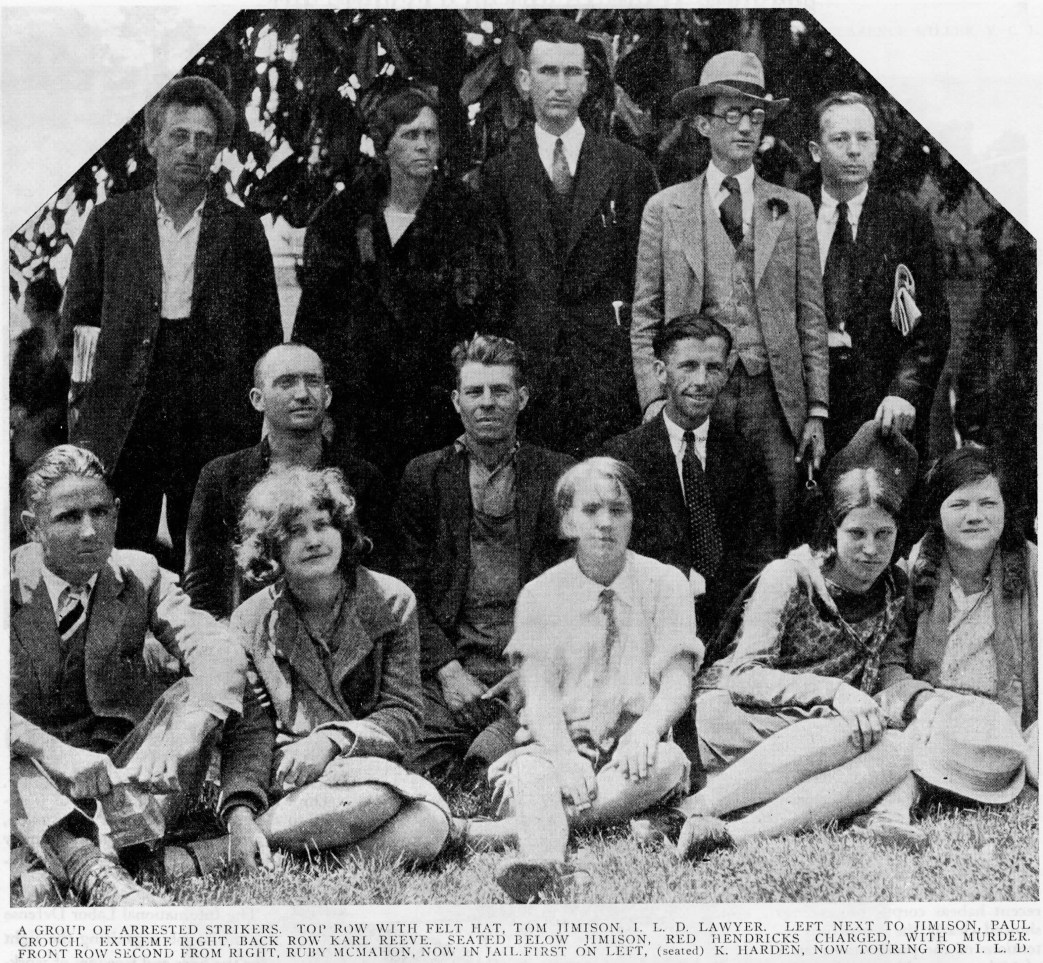

More than one hundred arrests were made. The prisoners were held incommunicado. Tear gas was forced into cells occupied by eight men and six women. Numbers were beaten to make them “confess.”

3. LYNCH THEM!

Lynch talk was everywhere. An attempt was actually made to lynch Fred Beal, arrested in Spartanburg and brought to the Monroe jail through South Gastonia for the convenience of the company thugs. Attorney Jimison, representing all the prisoners, was told by city officials that his life was in danger in Gastonia.

The Gastonia Gazette called openly for the blood of the strikers and organizers. In no American community have more brazen appeals been made for mass murder. The appeal failed because there was no response from the class which makes up the overwhelming majority of the population — the mill workers. It was impossible to give a lynching the requisite appearance of being a popular outburst.

Fourteen strikers and organizers are held without bail on two charges — murder and assault with intent to kill. 57 strikers and organizers are held in $2000 bail on the charge of assault with intent to kill.

The prosecution has engaged 16 attorneys. Every lawyer in Gastonia with one exception has been retained by Manville-Jenckes. Major Bulwinkle, chief counsel for the company, was engaged by the city council as special prosecutor after mill officials invaded the city hall en masse.

In addition to Bulwinkle, Hoey, Wooltz, Dolley, Whitaker and Magnum of the prosecution staff are attorneys for various textile companies. Clyde Hoey is considered the best attorney in the state. He is a brother-in-law of Governor Gardner.

Legally the prosecution has no case. It will try to railroad the defendants by perjured witnesses and pressure on the jury. It will try to make the issue Communism versus Americanism. It will try to split the local strikers from the “outsiders.”

The witnesses who swore to the complaints on which the warrants were issued are of the lowest type of human beings — expolice officers who have been fired for beating a woman with a blackjack, denizens of Gastonia’s little underworld who have just been released after doing a six months sentence, deputies who have been the most brutal towards the strikers, petty thieves and panhandlers — seven in all.

With nationwide interest in the case it is difficult even in Gastonia to railroad workers on such testimony. Consequently the stage is being set to prove a dark conspiracy— -to show that the police were deliberately lured to the headquarters so they could be shot down. With this scheme it is proposed to counter the defense claim that workers have a right to protect their persons and property from armed attacks — especially when they have been the victims of a previous attack.

What actually occurred is about as follows: (The information gathered from dozens of workers, strikers and others working in the Loray mill, can lead to no other conclusion.)

In order to forestall the impending strike the Manville-Jenckes company had issued instructions to destroy the tent colony and scatter the strikers and organizers by any necessary means. The police attack on the picket line was to have been followed by an attack on the headquarters and the strikers there.

Aderholt and his officers were to have used their authority to gain entrance to the headquarters property — they were the “legal 9 shock troops. The “Committee of One Hundred” was to come in then and do its stuff.

The resistance put up by the strikers upset this plan somewhat but the “Committee of One Hundred,” with white bands tied around their sleeves so they could identify one another, came later. They carried out the original plan — wrecked the headquarters, beat and arrested strikers and organizers. The intention was to smash the union, to drive the organizers out of Gaston county.

4. MANVILLE-JENCKES PARADISE

What is the background of this struggle? What are the conditions which the Manville-Jenckes company, its city and county and state officials are trying to maintain?

We quote from testimony given before the Committee on Manufactures of the United States Senate on May 8, 1929. This particular section of the testimony is entitled “Information Received From the Officers of Various Chambers of Commerce in North Carolina, South Carolina and Tennessee.” Joseph S. Wray, secretary of the Gastonia chamber of commerce, writes to the representative of a northern textile manufacturer:

“Wages in Gastonia range from 18 to 20 cents to 30 cents (per hour) for skilled workers…Children from 14 to 18 years of age can only work 11 hours a day” (Emphasis mine).

From another chamber of commerce secretary:

“From the viewpoint of the manufacturer the labor laws in North Carolina are as lenient as any in existence. The law at present allows a 60-hour week and an 11-hour day. There are no further restrictions on either day or night operation except as to the age limit of boys and girls. The age limit on boys and girls is the same and is a minimum of 14 years for daytime operation and 16 years for night operation.”

A worker in the Loray mill runs 38 cards for 11 hours per night, five nights per week. During the night shift 9,120 pounds of cotton are run through these cards.

The worker’s wage is $2.84 for 11 hours or $14.20 for the five shift week. The surplus value is approximately $25.52 per night or $127.60 per week per worker. (9,120 pounds of cotton works up into 56,720 yards of cloth selling wholesale at the plant for 5 cents per yard.) It is sold to mill hands for 60 cents per yard.

These statistics give a picture of the Manville-Jenckes paradise. It is to keep this rich field of exploitation, now invaded by the militant National Textile Workers Union, that the company is trying to send 14 workers to the electric chair and railroad 57 more to prison for long terms.

Not since the battle in Homestead have workers replied with greater determination and courage to the attacks of the armed forces of the capitalist class. The battle in the tent Colony in Gastonia symbolizes the advance of a new contingent of the American proletariat — the working class of the south. They take their place in our ranks as the echo of the gunfire in Gastonia is heard around the world. These new troops come as the class struggle sharpens everywhere and the shadow of imperialist war grows darker. They have been baptized in the fire of open struggle and have learned that the distinction in the south is not, any more than it is in the north, between American and “foreigner”, or between white and black,’ but between class and class — the owning and robbing capitalist class and the dispossessed and propertyless working class.

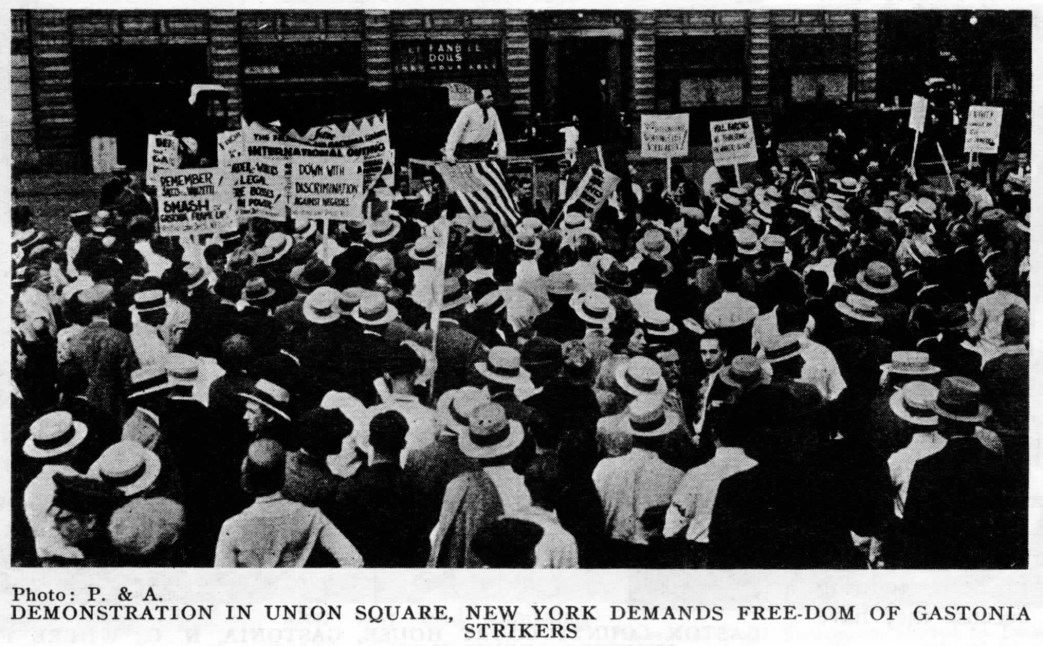

Only the swift rallying of the working class of the nation to the defense of these workers can tear them from the grip of the textile lords and their government. Around the International Labor Defense must be built the most powerful movement that has arisen in this country. The issue is clear: Must workers, men, women and children on strike, against who are mobilized all the black forces of capital, submit indefinitely to being driven, clubbed and slaughtered like sheep?

There is no doubt as to what the answer of the American masses will be. It will be in the same spirit in which the answer of the workers in the Gastonia district is being made. More requests for application cards of the National Textile Workers Union are coming than ever before. Around Gastonia is being welded a powerful chain of mill committees. The union is here to stay. It has survived the worst attack the textile barons could organize. The defense of its members and organizers is a sacred duty of the working class.

Let the bosses make Communism the issue in the trial. Communists are in the front ranks of the struggle here and it is against the Communist members of the union that the main fire of the prosecution is leveled. The southern textile workers will judge — by deeds.

The textile workers in North Carolina were betrayed by the bureaucrats of the United Textile Workers in 1920-21. No murder charges were preferred against these traitors. They retreated without a battle and left the workers to the mercy of the bosses. The Communist trade union organizers face the electric chair side by side with the local leaders.

For workers this is decisive. Fred Beal and Louis McLaughlin, New Bedford and Gastonia, north and south, communist organizer and southern textile worker, both charged with the same crime of rebellion against the mill barons and their armed forces — this is “the new south,” the new south where the working class Is forming its battalions for the great struggles to which the Gastonia conflict was a preliminary skirmish.

The New Masses was the continuation of Workers Monthly which began publishing in 1924 as a merger of the ‘Liberator’, the Trade Union Educational League magazine ‘Labor Herald’, and Friends of Soviet Russia’s monthly ‘Soviet Russia Pictorial’ as an explicitly Communist Party publication, but drawing in a wide range of contributors and sympathizers. In 1927 Workers Monthly ceased and The New Masses began. A major left cultural magazine of the late 1920s and early 1940s, the early editors of The New Masses included Hugo Gellert, John F. Sloan, Max Eastman, Mike Gold, and Joseph Freeman. Writers included William Carlos Williams, Theodore Dreiser, John Dos Passos, Upton Sinclair, Richard Wright, Ralph Ellison, Dorothy Parker, Dorothy Day, John Breecher, Langston Hughes, Eugene O’Neill, Rex Stout and Ernest Hemingway. Artists included Hugo Gellert, Stuart Davis, Boardman Robinson, Wanda Gag, William Gropper and Otto Soglow. Over time, the New Masses became narrower politically and the articles more commentary than comment. However, particularly in it first years, New Masses was the epitome of the era’s finest revolutionary cultural and artistic traditions.

PDF of full issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/usa/pubs/new-masses/1929/v05n02-jul-1929-New-Masses.pdf