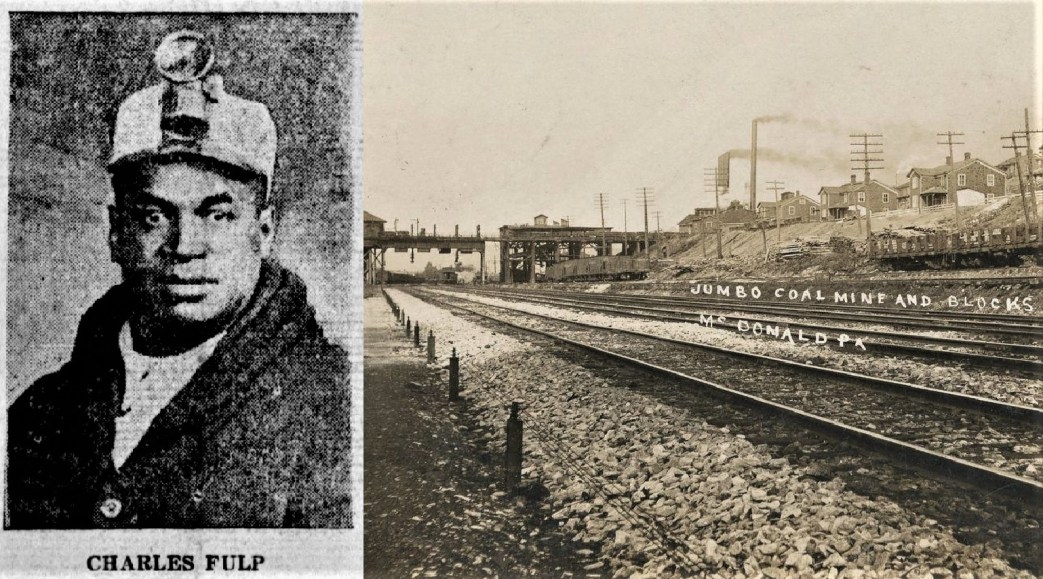

Meet working class hero Charles Fulp, progressive miner from Washington County, Pennsylvania. How many names and stories of stalwarts of our class and our struggle are now lost us?

‘Charles Fulp, Negro Miner Tell of Struggle’ from the Daily Worker. Vol. 5 No. 9. January 12, 1928.

Strikers Stand Solid in Coal Fields, Says Charles Fulp

The Negro miners in the coal fields of Pennsylvania have shown themselves to be made of the stem stuff of militant trade unionists. This is the message brought to New York by Charles Fulp, Negro organizer from the Washington County, Pa. coal field.

Tall, brawny, soft spoken but with a fearless eye, fresh from the coal mines, Fulp is now in New York with several of his fellow workers to aid the work of the Pennsylvania-Ohio-Colorado Relief Committee 799 Broadway.

Tells Miners’ Story.

Here several weeks, they have daily appeared before enthusiastic working class audiences, and by their simple recital of the tragic situation of the miners and their families succeeded in raising many thousands of dollars and great quantities of clothing for their comrades in the cold and foodless barracks back home.

Fuld, a real fighter, told a DAILY WORKER reporter of conditions in the Carnegie-dominated Washington County coal region; of the miners’ courage and solidarity despite great hardships, and of the failure of the bosses and their allies, the reactionary Lewis machine, to drive a wedge into the solidarity of the white and Negro workers by scurrilous attacks on the Negro race.

Was Secretary of Local.

Hailing from McDonald. Pa., 22 miles west of Pittsburgh, this coal digger has long been active as member of the United Mine Workers. He was for three years secretary of Local 2012 of the Primrose Mine, and its president for two years. In these positions he earned a reputation among miners thruout the Allegheny Valley as a hard-fighting progressive, never sparing himself to defend the miners’, rights. The workers, white and black, expressed their trust in him by making him head of their pit committee, picked by the men to voice their grievances to the mine superintendents.

The Primrose Mine, where Pulp worked, is owned by the Carnegie Coal Co., and employs about 375 men. The Carnegie Company in its 40 mines around Pittsburgh employs over 6,000 men. 2,600 of them Negroes. The fact that nearly every pit committee head is a Negro proves that the miners have realized the futility of racial quarrels in the face of their fight against the common enemies.

Attacked for Loyalty.

In 1924 Fulp was summoned to the pit bosses’ office and found himself before an assemblage of mins officials and district officials of the United Mine Workers. Present were the organizer of Sub-district 1 of Dist. 5 of the U. M. W. A., Busaarello, James T. Flood, president of the sub-district, and Pat Fagen, president of District 5. all cogs in the Lewis machine, smoking cigars with Superintendent Lindon and other mine officials.

“You’re fired for helping those God-damned Hunkies,” Lindon shouted at Fulp. Shortly afterwards right wing officials conspired in the same way with mine officials to get rid of Tom Ray.

For two years Fulp set quietly about instilling progressive ideas into the minds of the Washington County miners. In the meantime the operators, in open violation of their Jacksonville agreement with the United Mine Workers, began discharging progressive miners and putting nonunion men in their places. The reactionary district officials of the United Mine Workers made no protest against this, even encouraging members of Local 3533, at Midway, composed solidly of native born whites, many of them being kukluxers, to work with the scabs.

Strike Betrayed.

Finally, on April 1, 1927, the Jacksonville agreement for a $7.50 basic daily wage expired, and the operators refused to renew it, offering instead the 1917 scale of $4 a day for outside work and $5 for inside work. Only then did the International officials take action, ordering all the men out.

Then in the very conduct of a strike which they themselves had ordered, the reactionary Lewis machine lose the faith of the rank and file miners. The strikers found themselves in serious financial straights, for the officials of the union were withholding all strike benefits. In July, 1927, fourteen locals in the Allegheny met at Hawick and elected Steve Kurepa. Tony Minerich, Vincent Kamenovich and Fulp as a relief committee to present the miners’ case to the International officials of the U. M. W.

Form Relief Committee.

The officials were invited to a second conference in Pittsburgh, but refused to attend. Fagen, president of District 5, and Thomas Kennedy, International secretary and treasurer, met their pleas for funds with “Go to Hell,” and when the miners told them their families were starving, Kennedy said, “Eat grease.”

The five progressives thereupon organized the Pennsylvania and Ohio Miners’ Relief Committee with headquarters at Cloakmakers Union Hall, Pittsburgh, later removing to present quarters, 611 Penn Ave. Tony Kamenovich was chosen secretary, Minerich chairman, and Fulp field Organizer.

Meanwhile scabs were being imported from outside, while the United Mine Worker officials were doing their best to break the strike.

Among the scabs less than a third were negroes, yet Lewis officials tried to foment discord among the strikers by telling them the negroes were going back to work and scabbing on them. They told the workers that Fulp was receiving money from the mine owners to feed the men, and that Fulp would later betray them into signing a bad agreement. These silly tales were laughed at by the men, who knew Fulp s sterling honesty.

The negro strikebreakers, Fulp revealed, were trapped into scabbing, labor agents coming down to the southern farms and telling them about “wonderful farm jobs” up north. Once the negroes reached the mines they were placed under guard and held as prisoners. But Fulp got to many of them and many joined the strikers after eluding the guards.

In Constant Danger.

Fulp’s life is constantly in danger in Washington county. Both the bosses and the Lewis machine are out to get him. He is always followed by stoolpigeons; at night a guard of strikers watches his house ever since an attempt was made on him by two unknown assailants while he was asleep early in the strike.

Fulp stressed the point that the struggle is a rank and file drive against dishonest Lewis machine officials in the union as well as a fight against the operators for a decent living wage.

Fulp asks that all militant workers and their sympathizers send aid in the form of money and clothing directly to the Pennsylvania and Ohio Miners’ Relief Committee. 611 Penn Ave. Room 307, Pittsburgh, Pa.

The Daily Worker began in 1924 and was published in New York City by the Communist Party US and its predecessor organizations. Among the most long-lasting and important left publications in US history, it had a circulation of 35,000 at its peak. The Daily Worker came from The Ohio Socialist, published by the Left Wing-dominated Socialist Party of Ohio in Cleveland from 1917 to November 1919, when it became became The Toiler, paper of the Communist Labor Party. In December 1921 the above-ground Workers Party of America merged the Toiler with the paper Workers Council to found The Worker, which became The Daily Worker beginning January 13, 1924. National and City (New York and environs) editions exist

PDF of full issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/usa/pubs/dailyworker/1928/1928-ny/v05-n009-NY-jan-12-1928-DW-LOC.pdf