A valuable source on the history of the Communist Party in Birmingham, Alabama where the Party had its strongest support in the South. All students of the Party’s work in the South and of Black Communism in the 1930s will find this of interest.

‘The Communist Party in the Birmingham Strikes’ by Nat Ross from The Communist. Vol. 13 No. 7. July, 1934.

FOLLOWING the World War, in the period 1919-1922, a number of big strikes in the coal, steel, and railroad industries took place in the Birmingham region. The strikes were defeated and the unions smashed on the rock of division between the white and Negro strikers. Such were the bitter fruits of the Jim-Crow policy of the A. F. of L. officialdom. For a number of years a feeling of mutual distrust continued in the ranks of labor. There was even a tendency toward pessimism among some sections of the workers. From 1922 until the latter part of 1933, no strikes of importance occurred. Even some of the Communist Party members declared that the Birmingham workers would never fight or stick together because the white workers, they claimed, hated the Negroes and called them scabs and the Negroes disliked and distrusted the white workers. But the Party leadership hammered away against these opportunist explanations of the mood of the masses. The Party explained that the miners and steel workers of the Birmingham area would stand in the forefront in the revolutionary struggle in the South. The basic Birmingham proletariat was restless under the sledge hammer attacks of the capitalist class. The Party made the Birmingham area the main point of concentration in its work in the South.

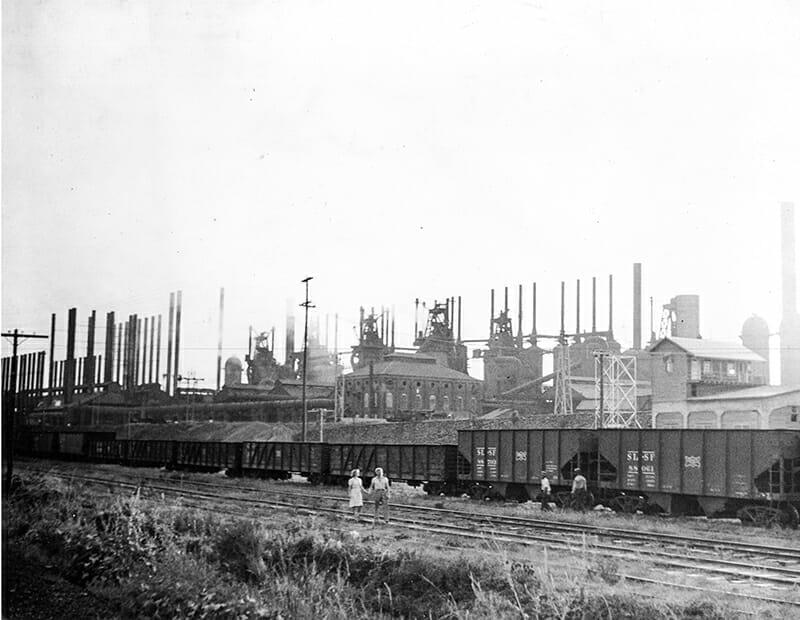

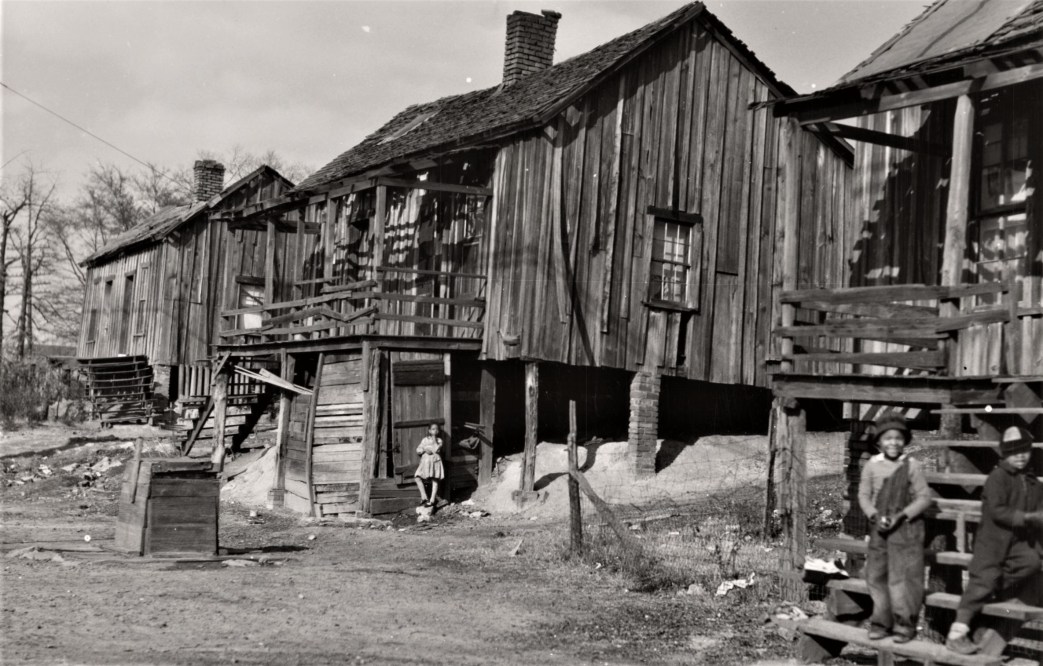

Birmingham was unique since it was the only place in the United States, if not in the whole world, where the main raw materials for steel—coal, iron ore, and limestone—were found side by side. The Tennessee Coal, Iron and Railroad Corporation, known as the T.C.I. (United States Steel subsidiary), along with three other steel corporations, controlled the lives of over forty thousand of their steel] workers and miners. The Party recognized that these so-called backward Southern Negro and white slaves of the steel corporations would some day surge forward in the forefront of the American revolutionary struggle. Their struggle would inevitably carry them into open conflict with the Steel Trust, whose giant power in the Birmingham area was built on a rotting foundation Birmingham lies on the fringe of the Alabama Black Belt. Its industry clearly shows the ear marks, in slightly varying forms, of slave survivals in the share-cropping system of the agrarian Black Belt. Four out of every five workers employed in steel and mining are Negroes brought in from the cotton fields. The white workers in the main also came from the Black Belt fields, while Birmingham industry was being built up during the first two decades of this century. The wages of the Negroes were lower than those of the workers in any other section of the United States. The wages of the main mass of white workers were also at a starvation level. The diet was not much better than the pellagra diet in the cotton fields. The Negroes were given the heaviest and dirtiest work. Convict labor flourished, especially in the coal mines. The Negro masses were Jim-Crowed in back alleys, and forced to live in tumble-down shacks. Company towns were guarded like prisons. Wages were paid in scrip, and the workers were forced to trade at the company stores, where the prices were such that the workers spoke of them as “robbery without a pistol”.

The Steel Trust controlled everybody and everything. The labor union was taboo. Even six months ago when the A. F. of L. tried to hold a union meeting in a public park in the T.C.I.-controlled steel town of Fairfield, the meeting was prohibited on the ground that bringing Negro and white workers together was a violation of the Jim-Crow ordinance. In practice the N.R.A. and the Jim-Crow Bourbons were working hand in glove. The stench of the slave market filled the Birmingham steel towns and mining camps. From the very outset, the Party pointed out that this stench must be wiped out as a step toward progress. Unity instead of Jim Crowism became a rallying slogan. The white workers could improve their own conditions only if they solidly united with the Negroes in the fight for better conditions and equal rights for the Negro masses. The key to unity lay in unionizing the Southern masses on the basis of united struggle.

Yet as late as the end of 1933, our Party in the Birmingham district, although leading the historic struggles of the share-croppers and the struggles for freedom of the Scottsboro boys and for the needs of the unemployed, did not really begin to put into practice the main instructions of the Open Letter. These instructions were made even more specific in the guiding Letter of the Central Committee, addressed in January, 1934, to the Birmingham district, which declares:

“Because there is a large organized mass farm movement (sharecroppers) which looks for guidance to the Party, because the main vital roots for the organized struggle for the right of self-determination are found in the farming mass of Negroes in District 17, precisely for these reasons is it all the more extremely necessary to build the Communist Party in District 17 in the most solid position in the basic industries.”

These instructions were still further amplified and concretized in the resolution adopted at the District Convention in March, which laid down a definite: policy of concentration, the building of the Party in the big industries, and the development of a fighting trade union movement as indispensable pre-conditions for revolutionary leadership of the big strikes which were already in the air.

RAPID GROWTH OF TRADE UNIONS

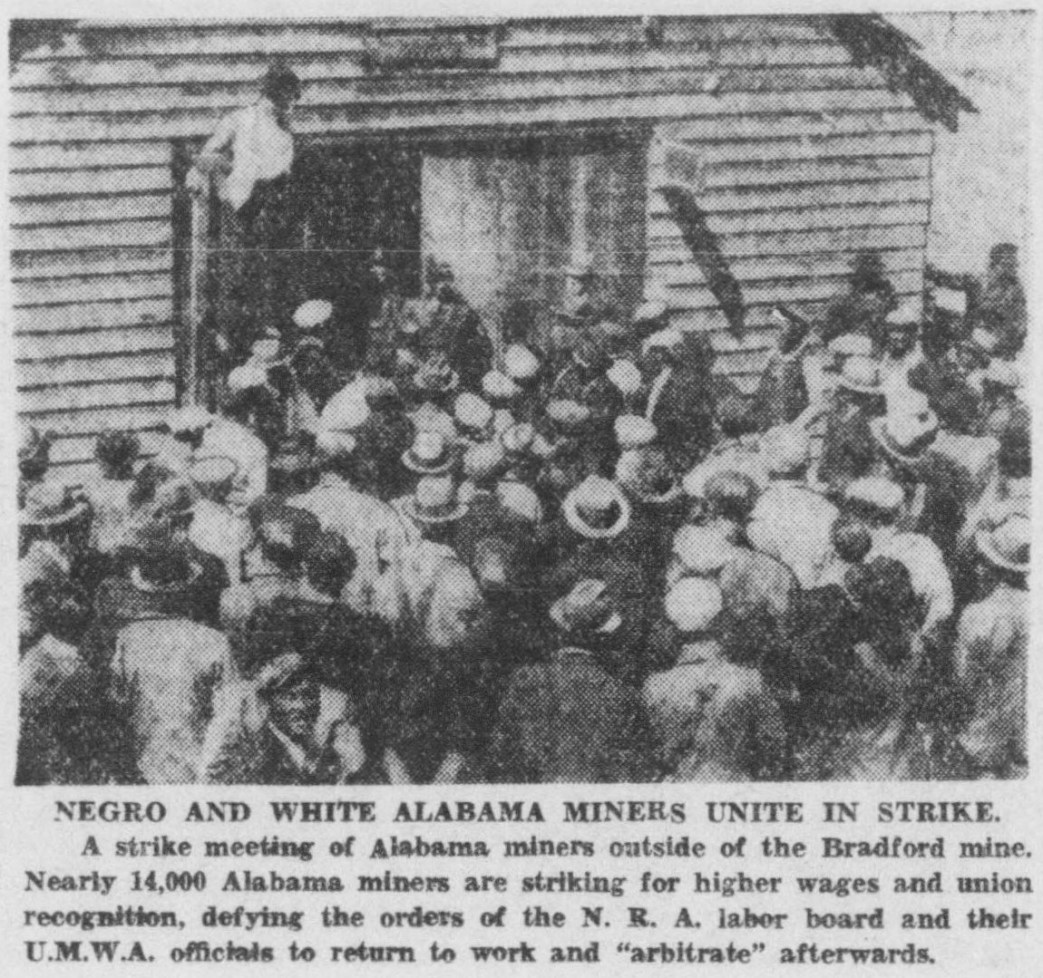

In the past year Birmingham has become unionized. Discontent was growing among the masses of workers and they saw the need for collective action. For a time they took seriously the glib promises of Section 7-a of the N.R.A. But the four years’ campaign and struggles of the Party in the Birmingham area for the unity and unionization of white and Negro workers had not fallen on barren ground. With scores of paid organizers in the field, the A. F. of L. was soon able to organize almost all the 21,000 coal miners, and the 8,000 ore miners in the Alabama field. Progress was made in unionizing some of the steel mills, as well as in other industries in Birmingham. Throughout this period the Party called on the workers not to trust the A. F. of L. bureaucrats, but to take the leadership of their unions into their own hands. The workers joined the unions because they wanted better conditions. White and Negro workers were members of the same union, and they began to feel their power. These workers wanted their union recognized and they wanted higher wages, which meant a fight against the slave wage-differential established by the N.R.A.

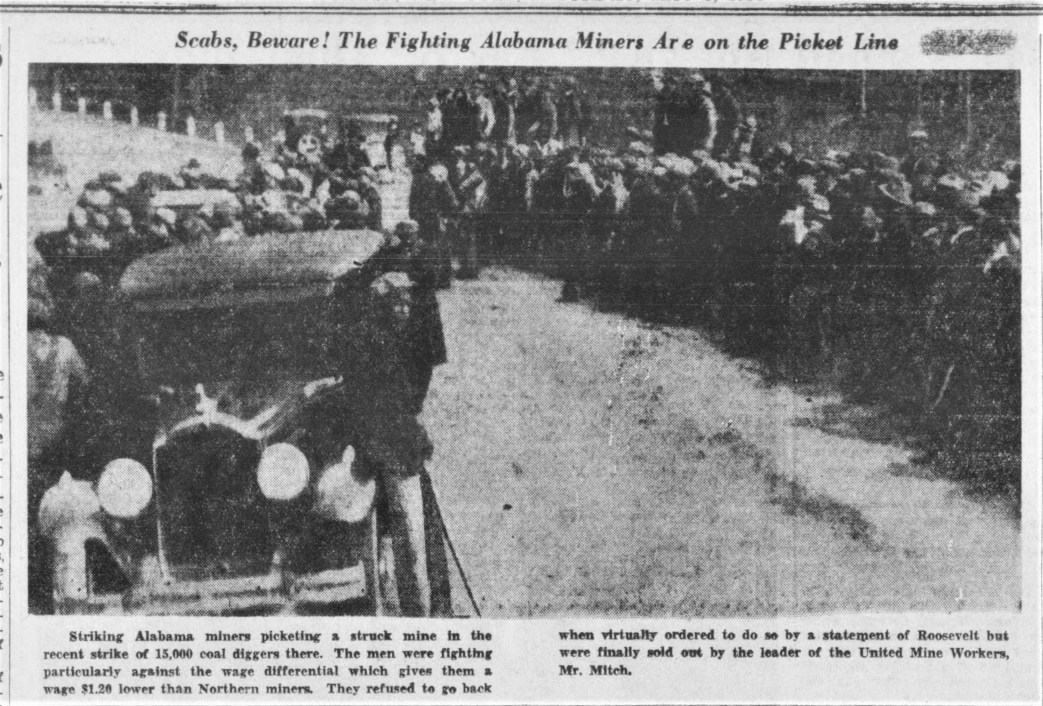

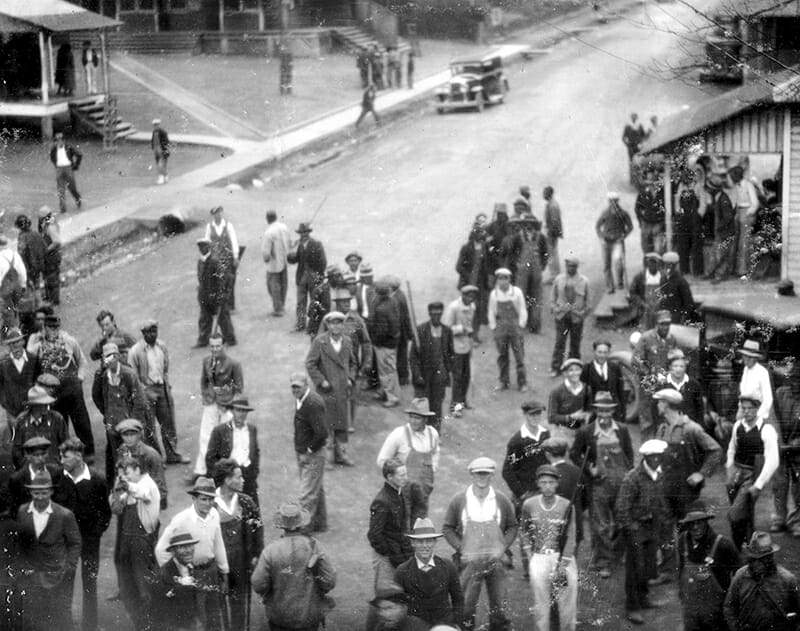

With the beginning of this year, sporadic strikes broke out in the coal fields. Two thousand laundry workers struck, tying up every laundry and cleaning plant in Birmingham. Shirt makers struck; C.W.A. and then relief workers, went on strike. The smouldering resentment of the Birmingham proletariat was bursting into flame. Cafeteria workers, butchers in the chain stores, packing house workers are on strike while this is being written. Workers in the Selma Manufacturing Co. textile mill, preparing for strike, have been locked out. Following the strike in the commercial coal mines in March, came the general coal strike of the commercial mines and captive mines of the Steel Trust in Alabama. Eight thousand ore miners tied up all the ore mines in the Birmingham region. The Republic Steel men struck on April 24, making the first breach in the steel industry in Birmingham in thirteen years. All of these strikes involve the question of the recognition of the A. F. of L. union, and the fight for higher wages. All categories of workers are involved—men and women, youth, white and Negro, skilled and unskilled—and 99 per cent of these strikers are native Americans. Beyond the lynch clouds the dim light of a new day is dawning in the South as white and Negro union brothers stand shoulder to shoulder on the picket lines, facing the machine guns of the National Guards.

THE GREAT GENERAL COAL STRIKE

In this article I want to draw some lessons from all of these strikes, with special emphasis on the coal- strike. As I write, the general ore strike still continues. The Republic Steel men are still out, and the steel situation is at the breaking point. The strike of the coal miners of practically all the commercial mines was ended in the middle of March by 2 an agreement which raised the basic pay of inside skilled workers from $3.20 to $3.40 a day; the main mass of miners were left in the same miserable condition as they were before the strike; they had not even gained recognition of the U.M.W. of A. The miners went back to work, but they were cursing as they entered the pit mouths.

On March 31, General Johnson issued an order raising the basic day rate for skilled inside men in the Alabama mines from $3.40 to $4.60. While this rate still maintained the differential compared with the rate in the Eastern fields, it was, nevertheless, a big increase. This move of Johnson’s was an effort to prevent a nation-wide coal strike, as well as general strikes in other basic industries, which were imminent at the time. It was also a move of the big corporations to put the small independent mines of the Southern fields out of business. It was furthermore a maneuver to pacify the rapidly stirring Negro masses and to cover up the increasing lynch and Jim-Crow character of the New Deal, by appearing to attack the Southern differential whose main victim was the Negro masses. It soon became clear even to the General himself, that he had overstepped himself and that the mounting chaos and confusion in the N.R.A. had got the better of him.

The Alabama coal operators answered the N.R.A. order by taking out an injunction in Federal Court against paying the increased wage. While it was clear from the outset that the N.R.A. officials and the Alabama coal operators would come to an agreement, the reconciliation of the miners was a more difficult task. The miners struck. They demanded the $4.60 rate. They wanted to get rid of the differential. They wanted to know why it was that digging a ton of coal in Alabama was worth less than in Pennsylvania. In the first week of the strike every commercial mine was closed down. But the mines of the steel corporations remained at work.

In the second week in April, the 21,000 miners of the giant captive mines, influenced by the Party and especially its shop and mine bulletin, The Blast, went on strike. Every mine in the Alabama field was shut tight. In this situation the Party pointed out that the miners could win their fight for recognition of the U.M.W. of A. and for increased pay only if the rank and file took over the leadership of the strike, dislodged the union bureaucrats, and prevented by mass picketing the attempt to bring scabs into the mines, with white and Negro miners standing side by side in solid ranks. The strike continued for a whole month. The mines were kept shut as mass picketing went on night and day. The miners were fighting mad—they were out to win. White and Negro miners held together. Such militancy and solidarity of the strikers had never before been seen in Birmingham. The solidarity of the strikers infuriated the bosses and the militancy of the Negro miners drove them into a frenzy.

The Birmingham News declared: “Groups of armed strikers, composed largely of Negroes, remained in virtual command of the T.C.I. mines.”

The Birmingham Age-Herald, the other organ of the T.C.L., declared: “The fact that Negro miners have become conspicuous in clashes with officers is a fresh and be-deviling factor.”

In an editorial the same paper said: “The inescapable truth is that a continuance of strikes amounts to playing into the hands of Communists. The wholesale unionizing which has taken place in recent months has included Negro as well as white miners. As a matter of organizing strategy, that was a sound step, although it does run counter to the practice of the A. F. of L. in the past. [That is to say, if the A. F. of L. doesn’t organize the Negroes, they will flock wholesale to the Communists.] But as things have worked out, Negroes have been conspicuous in demonstrations and other activities. What the arming of people who nurse their own racial grievances could lead to must be left to the imagination.”

But in the meantime the miners saw in the Party slogans the expression of their needs. Of the influence and prestige that the Party gained among the miners, perhaps the most eloquent testimony during the height of the strike was the statement:

“The T.C.I. officials have laid the responsibility for much of the unrest of the county at the door of Communist agitators.”

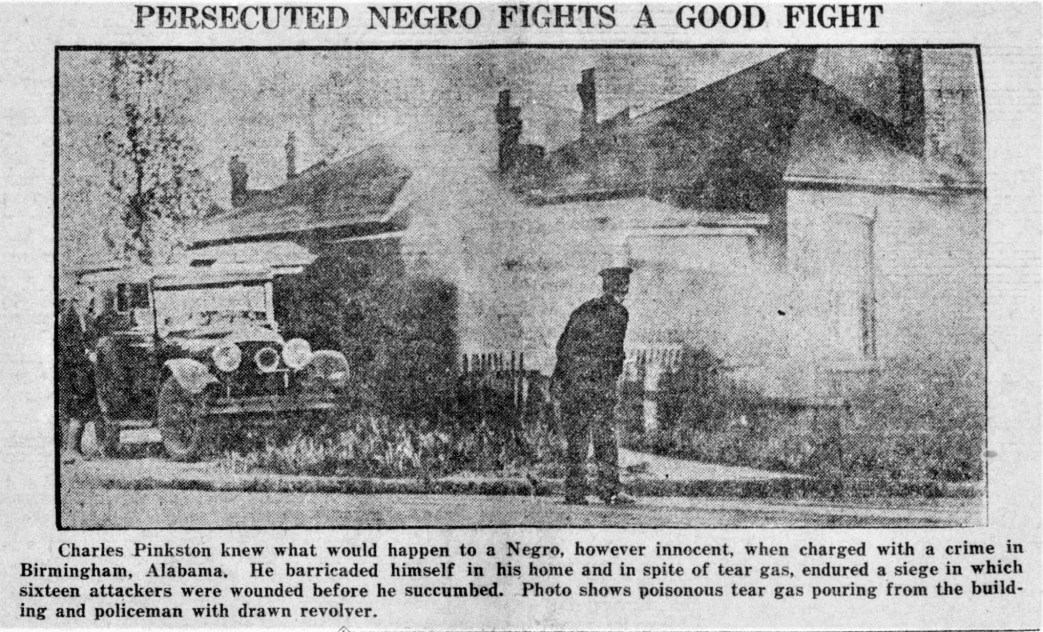

The corporations tried in many ways to break the strike. The T.C.I. was especially active because it was the miners of the T.C.I. who had taken the front rank in the display of revolutionary militancy, in the remarkable unity and solidarity of the miners in their mass picketing and in their refusal to abide by the sell-out instructions of the district bureaucrats of the U.M.W. of A. At this point the press tried to whip up a lynch spirit. It claimed that a Negro had attempted to rape the wife of none other than a T.C.I. deputy. The two police officers at the head of the Birmingham “Red” Squad were placed in charge of the hunt for the imaginary Negro rapist. But, despite all the tactics of the bosses to break the strike in the traditional way by whipping up the lynch spirit and dividing white and Negro, they had no success.

The Birmingham workers were watching the strike. They knew that the miners were fighting for the interests of all the workers. The solidarity of the white and Negro miners affected the other Birmingham workers. The remarkable militancy of the Negro miners led the average white worker to change his tone from “the Negro is a scab”, to “the Negro is a damn good union man and a real fighter”. And the solidarity actions of the white workers with the Negroes on the picket lines were fast dissipating the century-old distrust of the Negro masses toward the white workers.

The spirit of the Birmingham proletariat was high as the miners fought on. There was talk of a general strike. Workers were saying, “Now is the time for all union men to stick together”. In this situation the Party explained again that it was necessary to strike a solid blow at the Steel Trust. The 8,000 ore miners (all the ore mines are captive mines) were stacking up ore for the steel mills, while their brother coal miners were striking against those very same steel mills. The Party, therefore, called on the ore miners and the steel workers to join the strike, and all workers in Birmingham were urged to support this great struggle. In one of its most important leaflets issued during this whole strike period, the Party declared:

“The miners’ strike must be won! They can win the war against the N.R.A. slave differential with the support of the steel workers and the ore miners. Unless the miners win the strike, it means that the bosses will batter down the wage standards of the miners, and open fresh attacks on all Southern workers. Steel workers, ore miners, a victory for the miners is a victory for you! Join the strike for higher wages and to smash the differential.”

While the coal strike was nearing its end, the steel workers of Republic struck. In the meantime the pressure among the rank-and-file ore miners was so great that the officials of the Smelter Union, despite all of their maneuvering, were forced on April 24, to issue a strike call for May 4. On May 4, every ore mine was shut down, and the strike, six weeks later, still continues.

In the meantime, fear of the spreading of the coal strike and the tying up of all of Birmingham by a general strike forced the N.R.A. to act quickly. On April 22, General Johnson withdrew his rash order of March 16. Instead of the increase from $3.40 to $4.60 in the commercial mines, the skilled inside men were to get $3.80 a day. There were nominal increases for other categories of miners. The working day was cut from eight to seven hours, with a five-day week, and despite all the promises, the union was not recognized. The Birmingham Post, in an editorial, put it frankly.

“The corporation (T.C.I.) does not recognize the United Mine Workers of America.”

But Bill Mitch, the District President of the U.M.W. of A., was anxious to herd the men back to work. He and the bosses were very much afraid of the May Day demonstration in Birmingham. They were afraid of the impending steel and ore strike. After three weeks of threats and browbeating, Mitch forced the miners back to work. The coal miners are working again, but they are talking strike. They are not satisfied. The union is not recognized. The slave differential of the N.R.A. still continues. The stench of the slave market still exists in the coal camps in many forms. The coal miners of Alabama will be heard from again—soon.

THE N.R.A.——-ENEMY OF THE SOUTHERN MASSES

The injunction against the N.R.A. order by the coal operators was followed by a feverish campaign to maintain the differentials. The independent Southern capitalists were especially active. The steel corporations were not directly involved in the March 31 order, which applied only to commercial mines. They had faith in the N.R.A.—instrument of Wall Street. They became involved only when their miners struck for the $4.60 rate. They knew in advance that things would be adjusted and the differential maintained. But the independent capitalists were fuming. At a meeting of three hundred industrialists from all over the South, which was held in Birmingham, one of their number declared, amidst wild applause:

“Sherman’s march to the sea was no more destructive than the N.R.A. is going to be to the South. Before it is over we may have secession.”

There was no question that there were growing difficulties in the camp of the ruling class. But the more able Southern leaders knew that the differential wage would be maintained by the N.R.A. For a while the Roosevelt Administration remained silent to maintain the illusions it had created in the minds of the miners. The main mass of workers, during the first phase of the strike, thought of the operators on one side, as against the Federal Government and the union on the other. It seemed to many of them a fight of the union and the N.R.A. against the coal operators. But this dilly-dallying of the N.R.A. began to disillusion the miners, and later the cry of the N.R.A. for arbitration on the one side, and its direct support of unparalleled terror and even murder of strikers began to expose the actual role of the N.R.A.

The militant fight for recognition of the unions and against the differentials was a life-and-death question. The Southern rulers were out to smash the unions and maintain starvation wages. And they received Roosevelt’s support because maintaining the differential was the N.R.A. method of slashing the wages throughout the country. A campaign of terror was let loose against the strikers. Hundreds of armed deputies were sent into the strike zone. Unarmed Negro pickets and union men were murdered in cold blood. Strikers were arrested. In one day fifty warrants were issued against strikers after two Negro miners in the strike had been murdered and a dozen wounded by deputies’ gunfire. The National Guard was placed on twenty-four hour duty in the strike zone. In the meantime, a series of bombings and dynamitings of homes, commissaries, bridges, etc., took place almost daily for a whole month, and still continues. While these terroristic actions were mainly the doings of company agents and provocateurs in collaboration with the police and the A. F. of L. officialdom, the blame was placed directly on the strikers and the Communists.

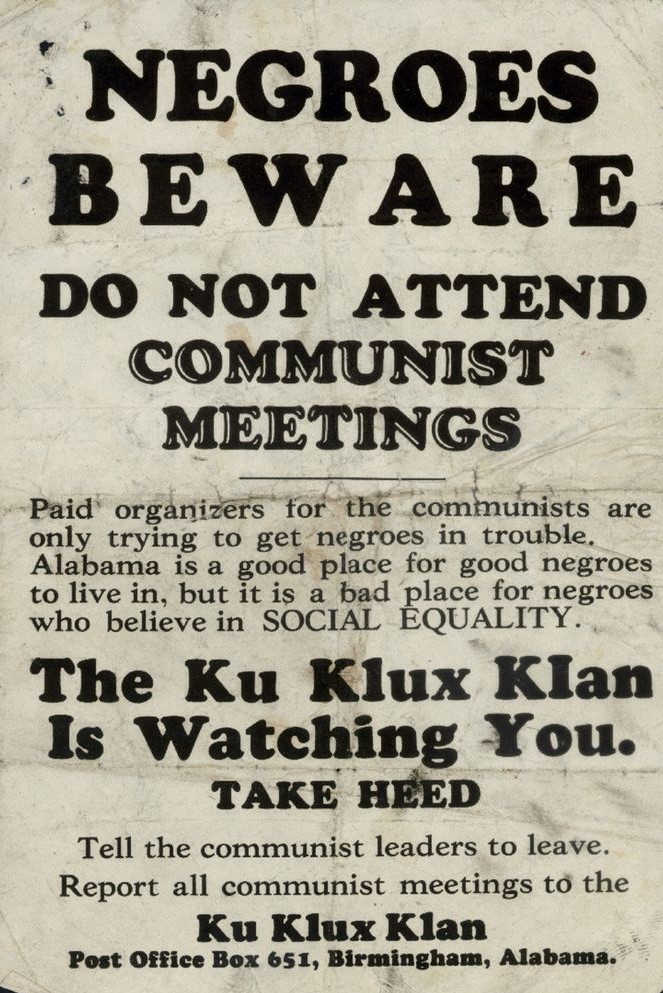

Every possible scheme was used to try to break the strikes. The police declared war against the Communist Party. Party leaders were arrested. Homes were raided daily for a week. The White Legion (a K.K.K. outfit with a new name), threatened Communists and strikers with their lives. They tried to mobilize the most backward elements of the white population for fascist violence. These fascists dictated policy to City Commissioner Downs. They worked together with the police. They directed the prosecution of the Communists in court. A tremendous development of fascist terror was apparent. And these very leaders of the terror drive were the main officials of the Roosevelt gang in Birmingham. In this way and by its tacit support the New Deal showed itself especially in later stages of the strike, as a Jim-Crow, lynch, and fascist deal against the Southern masses. The arrest of the Communists was meant to break the strike because the influence of the Party among the strikers was mounting. But it had no such effect. The militant self defense of the Communists in the barred court room rang out on the picket lines, and the slogan, “No settlement of the strike until all strikers and Communist leaders are released”, actually forced the release of the Communists, and the postponement of the strikers’ cases.

THE TREACHERY OF THE A. F. OF L. BUREAUCRATS

During all these strikes, the A. F. of L. bureaucrats betrayed themselves as capitalist agents in the ranks of labor. The plain fact is that against their will they were swept into the wave of strikes. They were at all times against spreading the strikes. An illuminating example is the following: On April 24, the steel men of Republic struck. On this same day Mitch called a hasty meeting of the Sayreton coal mine local of Republic and forced the men back to work on the basis of General Johnson’s April 22 order. The Party unit in the steel mill issued a leaflet calling on the coal and ore miners of Republic to strike with their brothers. The steel strikers marched on the Republic coal mine, and on April 27, after being at work only two days since the last strike, the Republic coal miners struck again. Mitch immediately issued a long statement to the press attacking the rank and file, especially the Communists, and further said:

“Unfortunately in some mines which are under joint agreement with the U. M. W. of A., efforts have been made to stop the operations of some mines in what might be termed a sympathy strike. No good union man would stop an operation that is working under agreement, and I am warning the members of U. M. W. of A. that they are under obligation to keep the mines in operation.”

In this way he once again forced the Republic coal miners back to work. Another brazen example was the action of President Webster of the Brighton Local of the Smelter Union, (Woodward Iron Company). All the ore miners had struck on May 4, and the Republic Steel men of the Smelter Local had already struck on April 24. This was the only local of the Smelters not on strike, and this reactionary company man at the head of the local declared that the steel workers at Woodward were well satisfied and would not join the strike of their 8,000 union brothers. It is interesting to note that only the other day this same Webster forced a resolution through his local which said:

“We are opposed to Communism, and will not accept the application of any man for membership who is tainted with its poison. We are convinced that anarchy in the so-called ‘higher social strata’ is the most prolific breeder of Communism among the ignorant, under-privileged class.”

Obviously Mr. Webster does not consider himself a member of the under-privileged class. So brazen was the treachery of the bureaucracy that in the Washington Coal Code hearings, Forney Johnson, attorney for the operators, reminded Mitch that he had confidentially promised not to ask for a wage increase for the miners for one year at the time the coal strike had been settled in March. So much so that The Birmingham Post editorially declared:

“In some cases it appears even where Mr. Mitch has sided with the operators in a disputed point, the miners have refused to listen to his orders.”

In the laundry strike the Birmingham Trades Council issued a leaflet in which it stated:

“The inside white workers are asking for a minimum wage of $12.50 per week. The colored inside workers are asking from 16% to 35 cents an hour. Over 80 per cent of these colored employees come in the 16% class.”

Certainly this impudent piece of lying and treachery which says that the Negroes wanted half the wage of the white workers, is not easy to surpass. The A. F. of L. officialdom stood by the N.R.A. and its slave differential wage for the South. However, at the recent State convention, they were forced to adopt a resolution condemning the differential, particularly because the Party had raised the question of the fight against the differential as one of the most pressing struggles of the day. And broad masses were translating this slogan into life.

In their attitude toward the Negro masses the bureaucrats showed their ugly Jim-Crow role. They stood for lower wages for Negroes at all times during the strike period. When Ed England, Negro coal miner, was murdered in cold blood, Bill Mitch issued a statement placing the blame on the heroic miner, and whitewashing the chief of police. After the I.L.D. spread leaflets in the mine fields demanding the conviction of the chief of police for murder and cash indemnity for England’s family, Mitch issued another statement calling for a federal investigation. He praised the National Guard. At all times the A. F. of L. officialdom tried to hold back mass picketing. International Representative Huey even went so far as to tell the T.C.I. coal pickets, the second day of the strike, to go home, throw away their sticks and clubs, “because the strike is won”. In some cases they even tried to set up Jim Crow picket lines; but the white and Negro miners smashed this damnable plan. Wherever possible the bureaucrats kept Negroes from leadership in the union and the strike. The A. F. of L. officialdom went so far as to endorse Bibb Graves, Democratic candidate for Governor, known as one of the outstanding leaders of the K.K.K. in its hey-day, which he is now reviving in his present campaign. While the A. F. of L. officialdom used every effort to keep the white workers from solidarity with the Negroes, the Negro misleaders played the role of sowing distrust among the Negro masses against the white workers. The Negro preachers talked the strike down at all times. Negro reformist leaders of the Civic League and N.A.A.C.P. issued anonymous leaflets calling on the Negroes to leave the unions. While their obvious attempt was to smash the unions, they claimed that this was the way to fight Jim-Crowism. In the present steel situation the T.C.I. has already handed out a large sum of money to the Negro preachers who are doing all they can to prevent the coming steel strike.

However, the A. F. of L. officials outdid themselves in one more way, and that was their unprincipled and vicious attack on the Communist Party. One of the central points on the agenda at the State convention was how to fight Communism which was “rampant in Alabama.” The Birmingham Post said editorially:

“There are evidences that Communism is spreading its subversive doctrines in the ranks of our laboring people, despite the warning of labor leaders that Communist ideas are furthest removed from the principles of trade unionism.”

The A. F. of L. officials even joined with the White Legion fascists in helping the authorities in their attempt to frame up Communist leaders on murder charges, in order to whitewash the murderous attack on the strikers by the Steel Trust deputies.

THE ROLE OF THE PARTY

It is very clear that the Party enjoys deep-going and wide sympathy, influence, and prestige among the masses of strikers. This was one reason for the frenzied attack against the Party by the ruling class and its sundry agents and agencies. The Party issued the slogans which came from the hearts of the masses. It explained the historic importance of the fight for union recognition and against the N.R.A. wage differential. It presented the urgent need for revolutionary strike leadership. It explained the need for rank-and-file control and leadership through elected strike committees. It called on the rank and file to go over the heads of their big officials. It urged the need for unity and solidarity among the white and Negro strikers, and called upon all workers to support the strikers. It urged the unemployed to join the picket lines and not to scab. It called on the strikers to demand the withdrawal of the National Guards. Many Communists were active in the strike leadership and on the picket lines. Only recently a rank-and-file delegation called on Governor Miller, demanding the withdrawal of the National Guards. Of course, the Governor refused. During every moment of the whole strike period which has lasted over three months, the Party has hammered away at the need for a solid fight on all fronts and for equal rights for Negroes. Dozens of examples testify that this crucial slogan found a sympathetic response also among the white strikers.

Despite all of the activity of the Party and its tremendous influence, we cannot be satisfied with our work. We must be frankly self critical, especially since the opportunities were so great. What were the main shortcomings in our work? First, while we issued correct slogans on the whole, without, however, sufficiently exposing the role of the reformists and especially the role of the N.R.A., we failed to prepare the organizational machinery to put our slogans into unified motion so as actually to consolidate rank-and-file groups in the locals. Our concentration policy was not concentrated enough. Instead of picking one or two key points, we picked nine mines and mills. It proved to be more than we could handle. At times our Party units and Sections did not recognize their role as leaders and fighters in the strike situation. We have about 75 Party members in the ore strike. Most of these are active, but not collectively, and not sufficiently through their mine units, and not at all through fraction work in the locals. Before the strike wave and even during the strike we did not sufficiently stress the development of local leaders as one of the pivotal questions. In the present ore strike, in one mining camp where we have 25 Party members, some of whom are local union leaders, we have temporarily lost contact with them because of the terror.

The amount of time and energy our leading comrades spend in developing these militant comrades will determine the role these comrades play in the strike. It is necessary to develop in advance conspirative methods of work, which our Party leadership failed to do. With the onrush of fascist development under the New Deal, failure to grapple with conspirative methods of work so that the Party can function during the most intense period of terror, is a crime against the Party and the instructions given us by the Thirteenth Plenum of the E.C.C.I. and the Eighth National Convention.

Most important of all, we failed to show simply and clearly the connection of the immediate struggle with our ultimate goal. That is why we did not recruit enough of the best strikers into the Party. What happened was that for a while the whole Party found itself swamped in the strike whirlpool, and we could not see beyond it. It is true that May Day came right in the midst of the strike struggles, and there was talk among the masses that May Day was the strikers’ day. Ore miners came in trucks even from distances of twelve miles, to the May Day demonstration. Yet we did not sufficiently explain the connection between the struggle against the differential wage and the struggle of the share-croppers, and between the struggle for the freedom of the Scottsboro boys and the whole fight for the right to self-determination in the Black Belt. This, despite the fact that the share-croppers themselves were being moved into struggle by the great Birmingham strikes. To put it more precisely, we did not show how only the revolutionary struggle which is leading toward a Soviet America can win higher wages and union recognition now.

This problem was clearly put before the whole Party in the simplest and fullest fashion by the Eighth National Convention, and all of us must solve this problem in our work, because it is the key to building a mass Party of revolutionary fighters, forged in the present and impending strike struggles in the United States.

There are a number of journals with this name in the history of the movement. This ‘Communist’ was the main theoretical journal of the Communist Party from 1927 until 1944. Its origins lie with the folding of The Liberator, Soviet Russia Pictorial, and Labor Herald together into Workers Monthly as the new unified Communist Party’s official cultural and discussion magazine in November, 1924. Workers Monthly became The Communist in March, 1927 and was also published monthly. The Communist contains the most thorough archive of the Communist Party’s positions and thinking during its run. The New Masses became the main cultural vehicle for the CP and the Communist, though it began with with more vibrancy and discussion, became increasingly an organ of Comintern and CP program. Over its run the tagline went from “A Theoretical Magazine for the Discussion of Revolutionary Problems” to “A Magazine of the Theory and Practice of Marxism-Leninism” to “A Marxist Magazine Devoted to Advancement of Democratic Thought and Action.” The aesthetic of the journal also changed dramatically over its years. Editors included Earl Browder, Alex Bittelman, Max Bedacht, and Bertram D. Wolfe.

PDF of full issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/usa/pubs/communist/v13n07-jul-1934-communist.pdf