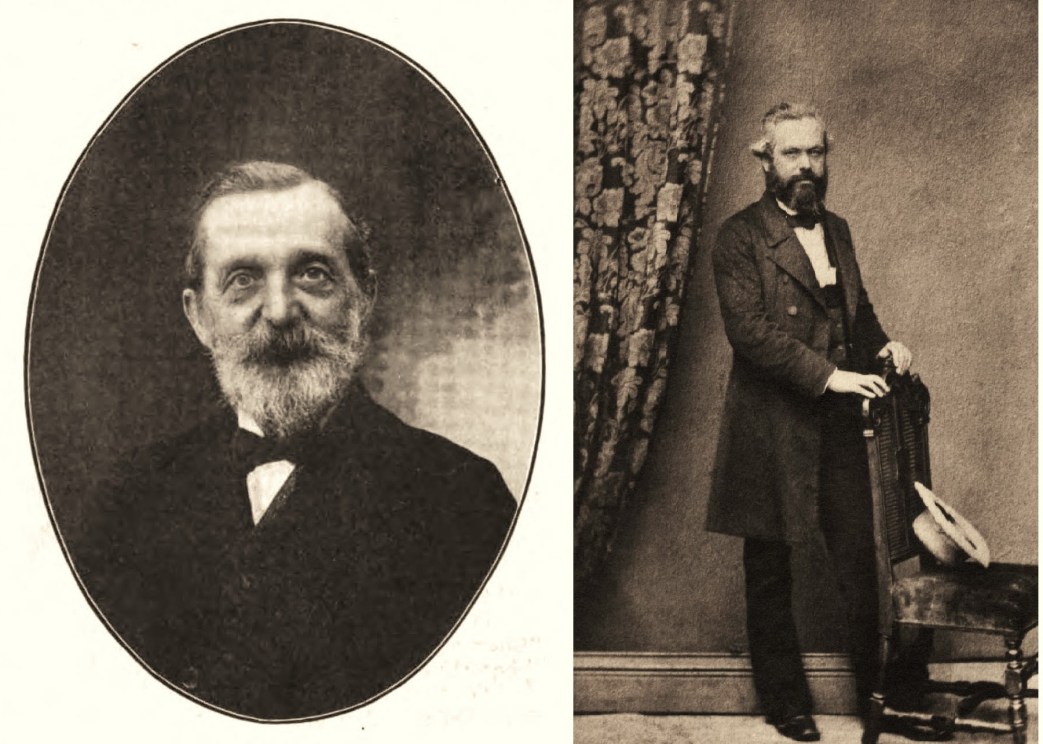

William Harrison Riley (1835-1907) was born in Manchester to a Methodist preacher and textile mill manager, became an early socialist and offers these delightful living memories as a comrade to Marx and Engels in the First International. Riley edited the IMWA’s British paper, ‘The International Herald,’ in the 1870s. A writer, farmer, and later Ruskin Colony member who moved to Massachusetts where he continued to write, was active in socialist circles, discoursed on Walt Whitman, and worked the land.

‘Reminiscences of Karl Marx’ by William Harrison Riley from The Comrade. Vol. 3 No. 1. October, 1903.

THE first time that I saw Marx was on the platform. He was the principal speaker at a meeting held to celebrate the noble work of the Commune of Paris. His speech was logical, powerful and effective, but not “fiery.” His manner of delivery was that of a deep thinker, and he used no orator’s tricks.

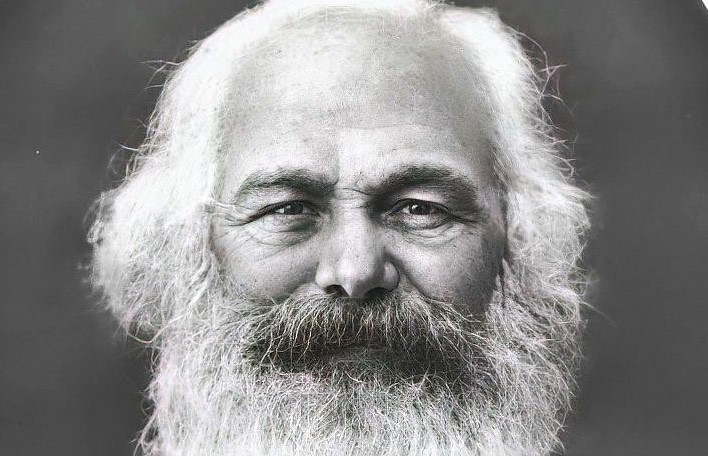

Marx was as good to look at as to listen to. Albert Brisbane, who saw him in 1848, said he was “short, built, solidly with a fine face and bushy black hair.” I am quite sure that Marx was at least four inches taller than the average height of Londoners. He was well built and remarkably good looking.

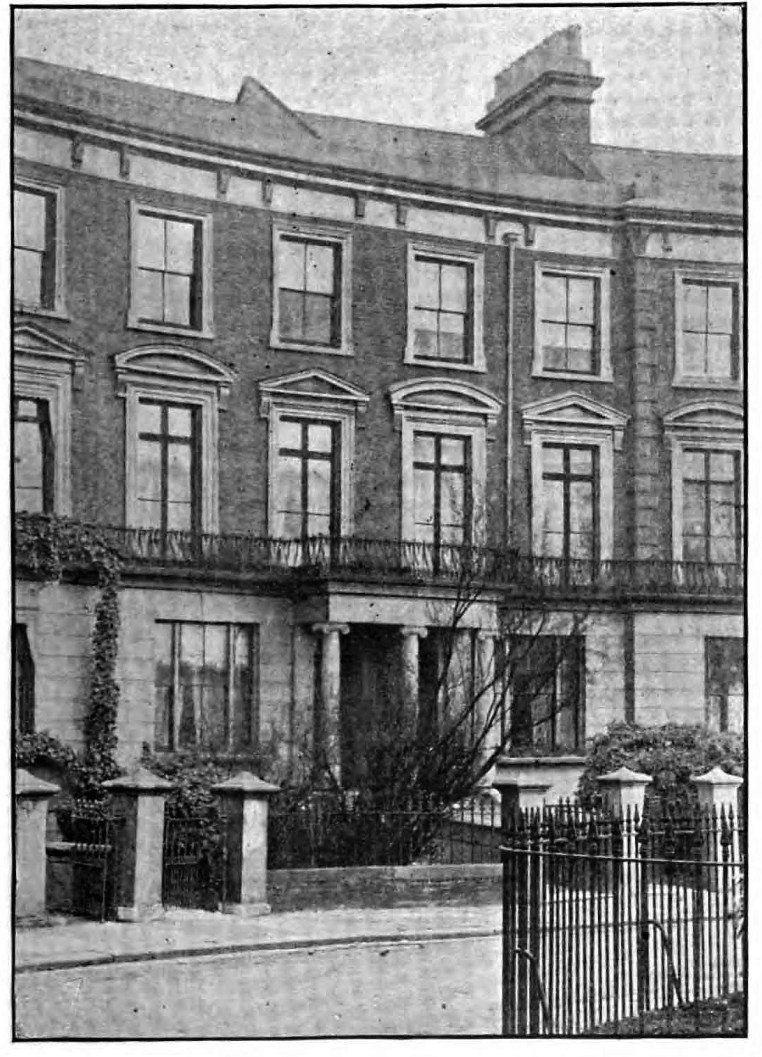

The next time that I saw Marx was at his house. No. 1 Maitland Park Road. He wore an old dressing gown, his bushy hair no longer black— was wildly pompadour. His den was profusely littered with books and papers. After asking me if I smoked, he invited me to try his tobacco. When our pipes were going satisfactorily he called my attention to a’ Spanish paper in which there was a translation of one of my editorials. I told him that I could not read Spanish and then he translated the introduction to the editorial.

Up to the time of my first visit to Marx, the reports of the meetings of the General Council of the International had been sent to the “Eastern Post,” a very common place newspaper. Marx told me that he wished to have the reports sent to my paper, the “International Herald,” and that he proposed to supply an official weekly supplement to the paper. He also informed me that he was writing an article on the land question, which would be at my disposal.

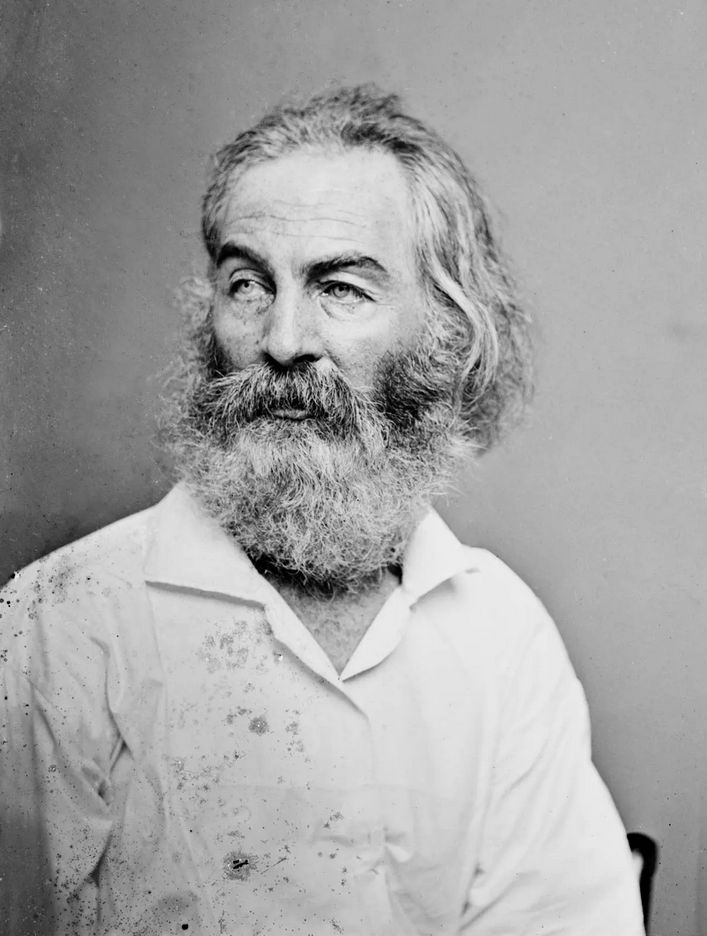

At my subsequent visits to Marx, the chief subject of discussion was about troubles in the Federal Council (entirely caused by the secretary, Hales,) but sometimes he wanted to talk about more agreeable subjects. At one of these meetings, the name of Walt Whitman was brought into the conversation. I think that Marx had not read any of his poems —even if he had ever heard of them— but he was evidently well pleased with some of the lines that I quoted, as, for instance, “Speaking of miracles, a hair on the back of my hand is as great a miracle as any.” Then I quoted a verse from the “Pioneers”:

“All the past we leave behind ; We debouch upon a newer, mightier world, varied world: Fresh and strong the world we seize, world of labor and the march, Pioneers! O, Pioneers!”

I quoted some other things, at the request of Marx, who seemed to be greatly interested, and then he tried to draw me out. He wanted to know something about my depth and breadth before taking me into his confidence, so he tried to make me do most of the talking.

Whitman’s treatment of theology pleased Marx, and he spoke approvingly of it. Then he referred to some of my writings – including “My Creed” – and we had a brief discussion. He asked me to try to prove that it is more reasonable to believe than to disbelieve in a continuation of existence after what is called death, and in the existence of superior intelligence to that of mankind. Marx took the agnostic position, and I do not think I could have found a more able opponent, but after a while he said, “You should know Thomas Alsop. He would like to hear your remarkable arguments, and I should like to hear what he has to say in reply.” When I told him that Alsop was already one of my best friends, he said, “You cannot find a wiser friend in all England.”

It was probably because of unresponsible and influential position as editor of the “Official Organ of the British Federal Council” that Marx occasionally catechized me, wishing to ascertain my qualifications for the position. One of the questions he asked me was, “Which of the Asiatic countries will be the future dominating power?” “Siberia.” I replied, and gave him my reasons, with which he seemed satisfied. At another time he asked me if I thought the United States would be the first country to adopt Socialism, and in reply to my opinion that France and Germany would take the lead, Spain and Italy be in the centre, and the Anglo-Saxons march in the rear, he said (as nearly as I can remember), “I am glad to find that you are not parochial, but that you are a citizen of the world.” The Internationalists addressed each other as “Citizen,” but I disliked the designation and frequently substituted Whitman’s greeting, “Comrade.”

At another time, Marx asked me if I had read Proudhon. When I replied that I had not, he said something to the following effect: “Some things you have written are peculiarly like some of the things he has written. I don’t suspect that you have copied from him, or from any body, and when you read the book I am now at work on I don’t want you to suspect that I have copied from you.” I suppose that I stared, for he smiled and said: “Well, I may decide to translate it into English, and then you may see some arguments that you have used, and others have used centuries ago. We have only worded them a little differently.”

One day, in 1872, Marx told me he wanted the United States Report of Immigration, and I said I had the latest and would send him a copy, which I afterwards did. He occasionally sent to me marked copies of Continental papers, and I have a copy of the Rules of the House of Commons that he gave to me.

Marx spoke highly of some of the writings in the “Herald,” but said that most of the writers were “patent pill mongers,” which was, unfortunately, only too true. He spoke bitterly of some of the trades union leaders, Potter (of the “Bee Hive”), Howell, Mottershead, and a few other “mercenaries,” and asked me if I was aware that almost all of the trades unionists in Spain were Socialists. He warmly approved my denunciation of the labor misleaders.

There were very few Internationalists in Ireland, but Marx seemed to take more interest in the work in Ireland than he did in our English work, or in the agitation in America.

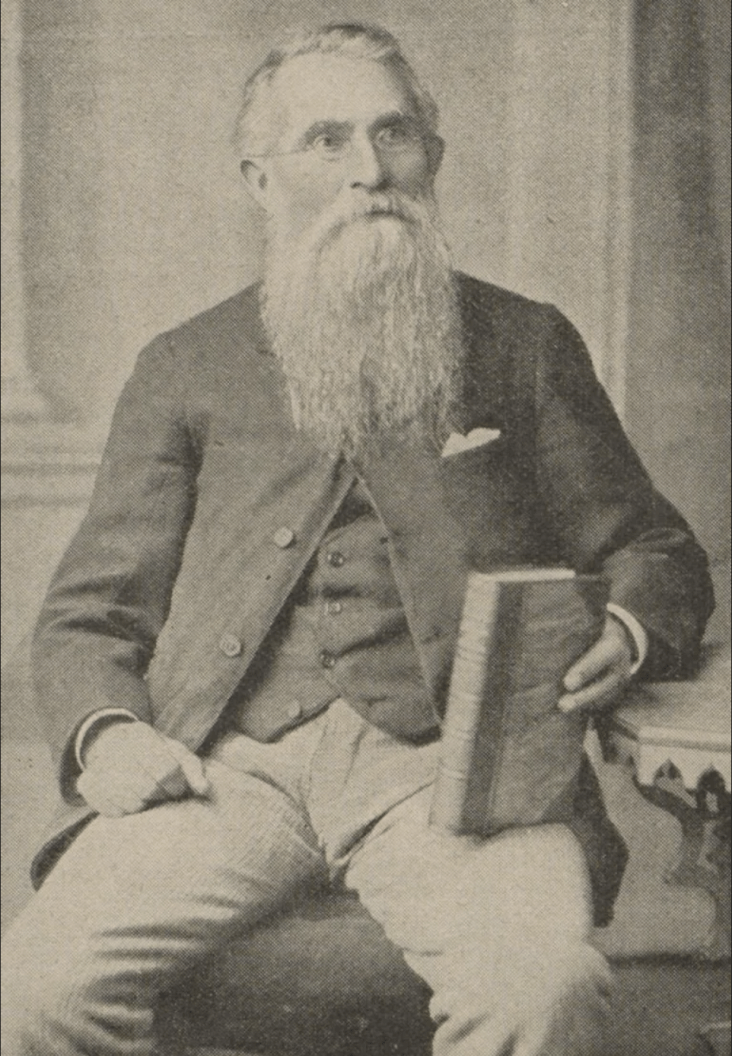

Lessner, a German exile, was one of Marx’s most intimate friends. He is yet living and should be able to supply more interesting information about Marx than I can give. I can only jot down a few disconnected recollections.

The only time that I was in the company of Walt Whitman, he asked me —referring to Ruskin — “How is the good man?” Marx also esteemed Ruskin most for his “goodness.”

I never heard Marx talk about pictures, sculpture, or poetry (except Whitman’s). He was not what is called a “Sentimental Socialist.” He was rigidly mathematical.

After the secession of the Bakounine insurgents, and the removal of the General Council to New York, I seldom saw Marx, and the few letters I received from him related only to the lamentable disruption of the association in England.

It has been said, “A prophet hath honor, except in his own country.” In 1872, there were not many people in England who knew anything of Marx, although a million knew of Odger and Bradlaugh. But the London “Times” editor was well aware of his great ability and his influential position, and Marx told me, on several occasions, “The ‘Times’ has sent a man to me again for special information.”

There are many unwise proverbs, and one of the unwisest is, “The voice of the people is the voice of God.” Carlyle said, “The population of England is twenty millions —mostly fools.” Few of the men we now consider heroes were esteemed by the populace, in their own time and country, and many of the noblest men that ever lived have been martyrs.

EDITOR’S NOTE: William H. Riley, who contributes the foregoing reminiscences of Karl Marx, played an important part in the old International Workingmen’s Association in England and saw much of Marx and his associates. In 1871 he was editor of the Leeds “Critic” and issued several pamphlets, including one on “Strikes.” In that year he joined the “International,” and in the year following went to London and became editor of the “Republican.” Later he became editor of the “International Herald,” the official organ of the British Federal Council, and, afterwards, of the “Herald and Helpmate” (Bristol) and the “Socialist” (Sheffield).

Strange to say. Mr. Riley attributes his “conversion” to Socialism to Whitman’s “Leaves of Grass,” a copy of the first edition of which he came across in Boston in 1857. Years afterward it was his good fortune to be the means of interesting Ruskin in Whitman. In response to a letter from Mr. Riley inclosing some quotations from “Leaves of Grass,” Ruskin wrote: “These are glorious things you have sent me. Who is Walt Whitman, and is much of him like this?” Ruskin’s interest in Whitman later was, as is well known, very great and sincere.

Mr. Riley returned to this country in 1880, and is now sixty-eight years young, as enthusiastic as ever in the Socialist faith.

His description of Marx as being “rigidly mathematical” must not be interpreted too literally as meaning that Marx had no taste or liking for poetry.

Far from that being the case, his familiarity with, and appreciation of, the great poets, ancient and modern, was remarkable. In his youth Marx himself wrote a number of poems, but seems to have grown out of that not uncommon habit of youth. Marx was indeed “rigidly mathematical” when the occasion required, but his literary tastes were surprisingly catholic and broad. He inclined to the romantic school and “Don Quixote”‘ seems to have been one of his great literary favorites. Of the poetry of his friend and countryman, Heinrich Heine, he was particularly fond as he was also of the work of that other great poet of his native land, Goethe. “Faust” and Dante’s “Divina Commedia” he knew almost entirely by heart and, it is said, I think by Lafargue, that he made it a rule for several successive years to read Shakespeare from cover to cover Homer was another of his favorite authors. His love for committing poetry to memory was inherited by at least one of his children, Eleanor, who used to pride herself that she could recite every line of the poetry of Robert Burns!

It would be a most interesting piece of work if someone would compile from Marx’s works all his many quotations from, and reference to, the great poets. Even the most casual reader of “Capital” must have noticed, and marveled at, their range no less than their appropriateness.

It is well that all such “Reminiscences” as the foregoing should be recorded and so preserved for the generations of the future, but is it not strange that there is as yet no adequate and reliable biography of Marx in any language? Surely the time for that has come!

The Comrade began in 1900 in the run-up to the launch of the Socialist Party, and was published monthly until 1905 in New York City and edited by John Spargo, Otto Wegener, and Algernon Lee amongst others. Along with Socialist politics, it featured radical art and literature. The Comrade was known for publishing Utopian Socialist literature and included a serialization of ‘News from Nowhere’ by William Morris along work from with Heinrich Heine, Thomas Nast, Ella Wheeler Wilcox, Edward Markham, Jack London, Maxim Gorky, Clarence Darrow, Upton Sinclair, Eugene Debs, and Mother Jones. It would be absorbed into the International Socialist Review in 1905.

PDF of full issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/usa/pubs/comrade/v03n01-oct-1903-The-Comrade.pdf