‘Uncle Sam – Buccaneer’ by Scott Nearing from New Masses. Vol. 2 No. 4. February, 1927.

DARING EXPLOITS OF STAR-SPANGLED PIRATE IN THE CARIBBEAN

UNCLE SAM needs another canal across the Isthmus. The Panama Canal is getting crowded and, besides, in time of war its locks and slides are indefensible against an attack from the air.

Nicaragua has the only alternative route, — through the San Juan River and Lake Nicaragua. To be sure, Costa Rico claims a voice in the matter as the San Juan River borders that country. But Costa Rico will be dealt with later.

Uncle Sam is now busy taking the canal site away from the people of Nicaragua to the accompaniment of “red propaganda” charges from Secretary Kellogg, pious utterances from President Coolidge, and a barrage of press lies involving Mexico with Nicaragua in a plot to destroy the supremacy of the United States in the Caribbean area.

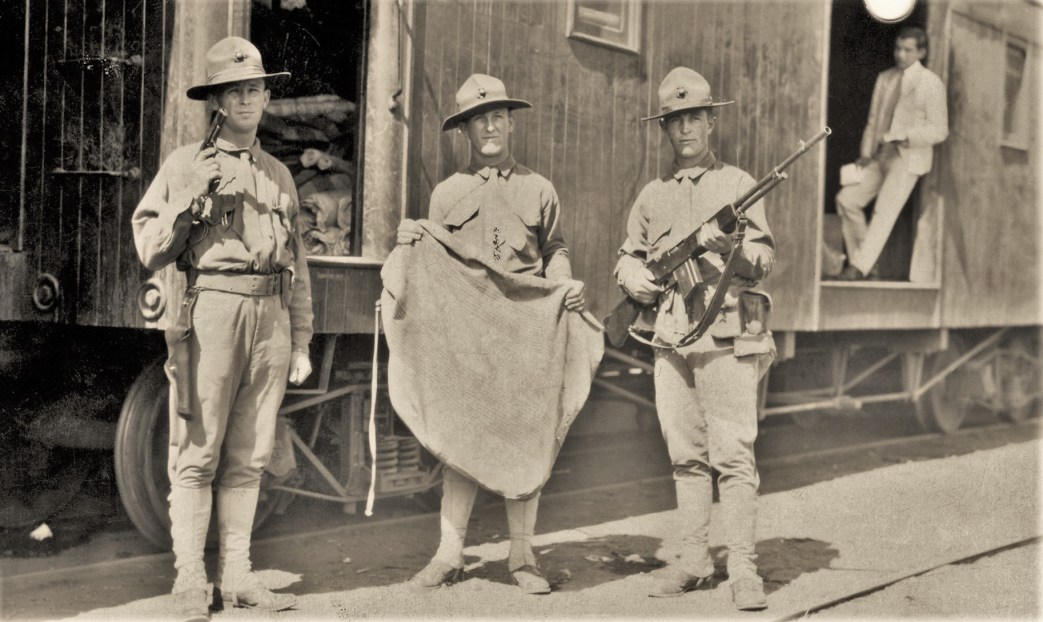

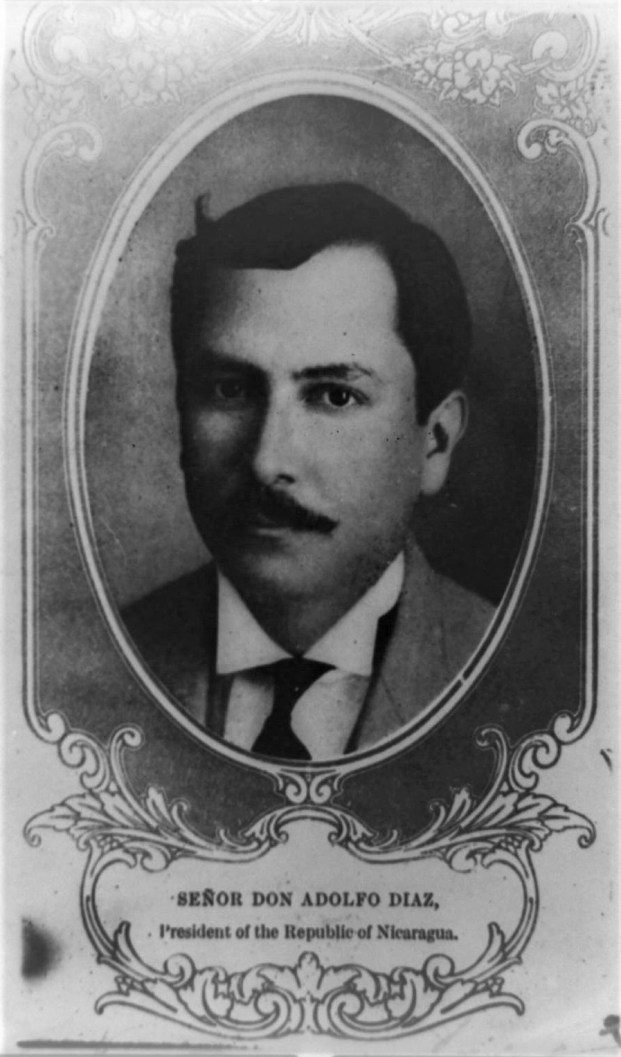

Fifteen United States war vessels are in Nicaraguan waters. Admiral Latimer, in charge of United States forces, has landed marines at various points such as Porto Cabezas, where the Liberals’ showed strength, established “neutral zones,” and ordered the Liberals either to disarm or leave. By such tactics the United States has thrown its diplomatic and naval authority around the government of Adolfo Diaz, Conservative, despite the fact that Diaz is so unpopular in his own country as to be quite unable to maintain himself without the United States marines.

Adolpho Diaz has been prominent in Nicaragua politics since 1909, when as a clerk in the office of an American corporation operating in Nicaragua, he advanced $600,000 to finance a revolution that was supported, recognized and defended by the U.S. State Department. Then the issue involved a loan by American bankers and a treaty giving the United States the right to dig a canal across Nicaragua. Diaz was for the U.S.A. then and he is for the United States now.

Diaz stated his case very frankly in a radio message to the New York Times, on January 8, 1927: “We do not look to Mexico, now in a state of chaos, but to the United States, the foremost nation in the world.” “We are convinced,” Diaz asserts, “that in the hands of the United States the national sovereignty and best interests of small Latin-American countries are secure, whenever any one of them finds it necessary, in a difficult moment, to seek the friendly aid of the United States.” “Will you walk into my parlor?” said the spider. “There you will see these confiding little Latin-American republics listed as ‘protectorates’ in all of the latest school histories.”

Two days later, January 10, Diaz coyly added, “I admit that in the re-establishment of peace I should be most happy to see a large loan contracted by my government in the United States.”

Chamorro and Diaz gained their control of the Nicaraguan government in 1925 by a military coup. Between 1912 and 1925, United States marines remained in Nicaragua. But in 1924, Diaz, despite the presence of the marines, was badly beaten in an election supervised by an “American expert.” Then the marines were removed long enough to permit of the Diaz coup. Now a year later, the marines are back in Nicaragua.

Diaz began his duties as president of Nicaragua on November 14, 1926. Within a week he was recognized by the United States State Department. On November 19th, the State Department announced that the co-operation of the United States had been offered toward establishing peace in Nicaragua. Immediately thereafter, Diaz requested and received the armed support of the United States Government. In his appeals for this support he admitted his government could not survive without it.

Diaz says quite openly that Nicaragua wants another United States loan. President Coolidge insisted quite as openly in his message of January 10th, that the United States is in Nicaragua to protect American business interests. Coolidge began by calling attention to “the present disturbances and conditions, which seriously threatened American lives and property, endangered the stability of all Central America, and put in jeopardy the rights granted by Nicaragua to the United States for the construction of a canal.”

There is no evidence cited to support this contention insofar as it refers to American lives and property. On the matter of the canal and of future loans, however, Nicaraguan opinion is anti-U.S.A., and Sacasa, Diaz’s rival, evidently represents that opinion.

Later in the same message Coolidge made himself even clearer: “If the revolution continues, American investments and business interests in Nicaragua will be very seriously affected, if not destroyed…The proprietary rights of the United States in the Nicaragua Canal…place us in a position of peculiar responsibility.”

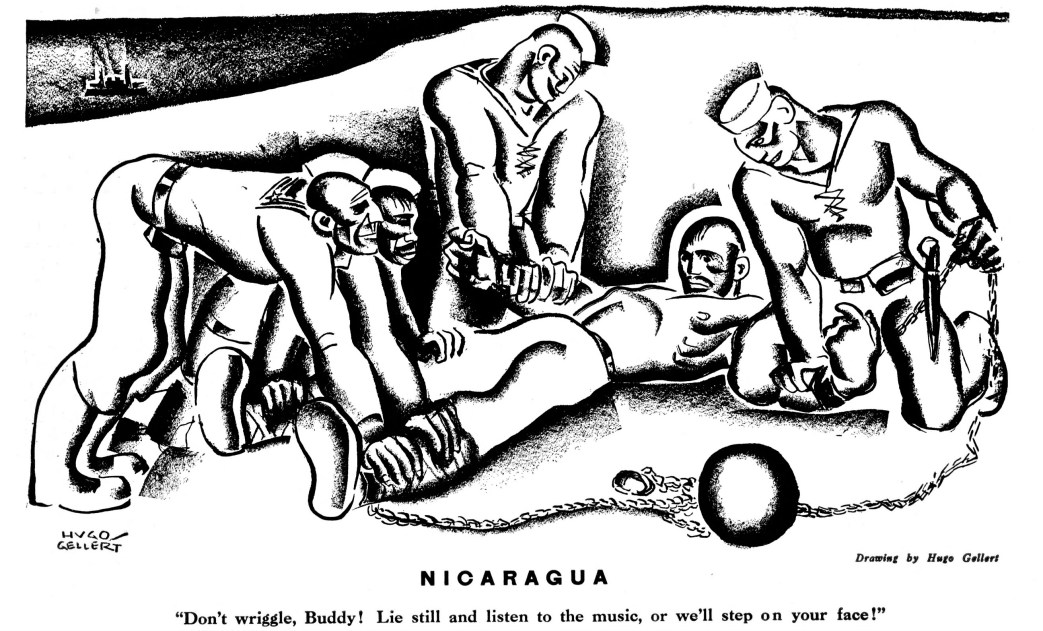

That is the story — “Investments,” “Business Interests,” “Foreign Bond Holders,” “Proprietary Rights.” Uncle Sam is in Nicaragua looking after hard cash, or its equivalent. He wants a piece of property and he has gone with a gun to get it. A humble citizen of New York City, who did the same thing in his private capacity, would get life under the Baumes law. As for Uncle Sam — he will get a new canal site.

A word about the contestants in this latest effort of the United States to establish its chain of protectorates around the Caribbean. Nicaragua is a country with an area less than that of New York State, and a population one-tenth as great as New York City. It is a poor country, without a navy and with an army about big enough to confront the police reserves from one New York precinct.

Lined up against this tiny atom of statehood is the U.S.A., richest nation in the world, with its vast resources and its overwhelmingly enormous military machine.

This is no fight. It is murder. And the United States will get away with it just as it got away with the revolution which Roosevelt engineered in Panama in 1903 when a stubborn Colombian Congress refused to turn over the Panama Canal Zone to the United States.

The New Masses was the continuation of Workers Monthly which began publishing in 1924 as a merger of the ‘Liberator’, the Trade Union Educational League magazine ‘Labor Herald’, and Friends of Soviet Russia’s monthly ‘Soviet Russia Pictorial’ as an explicitly Communist Party publication, but drawing in a wide range of contributors and sympathizers. In 1927 Workers Monthly ceased and The New Masses began. A major left cultural magazine of the late 1920s and early 1940s, the early editors of The New Masses included Hugo Gellert, John F. Sloan, Max Eastman, Mike Gold, and Joseph Freeman. Writers included William Carlos Williams, Theodore Dreiser, John Dos Passos, Upton Sinclair, Richard Wright, Ralph Ellison, Dorothy Parker, Dorothy Day, John Breecher, Langston Hughes, Eugene O’Neill, Rex Stout and Ernest Hemingway. Artists included Hugo Gellert, Stuart Davis, Boardman Robinson, Wanda Gag, William Gropper and Otto Soglow. Over time, the New Masses became narrower politically and the articles more commentary than comment. However, particularly in it first years, New Masses was the epitome of the era’s finest revolutionary cultural and artistic traditions.

PDF of full issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/usa/pubs/new-masses/1927/v02n04-feb-1927-New-Masses.pdf