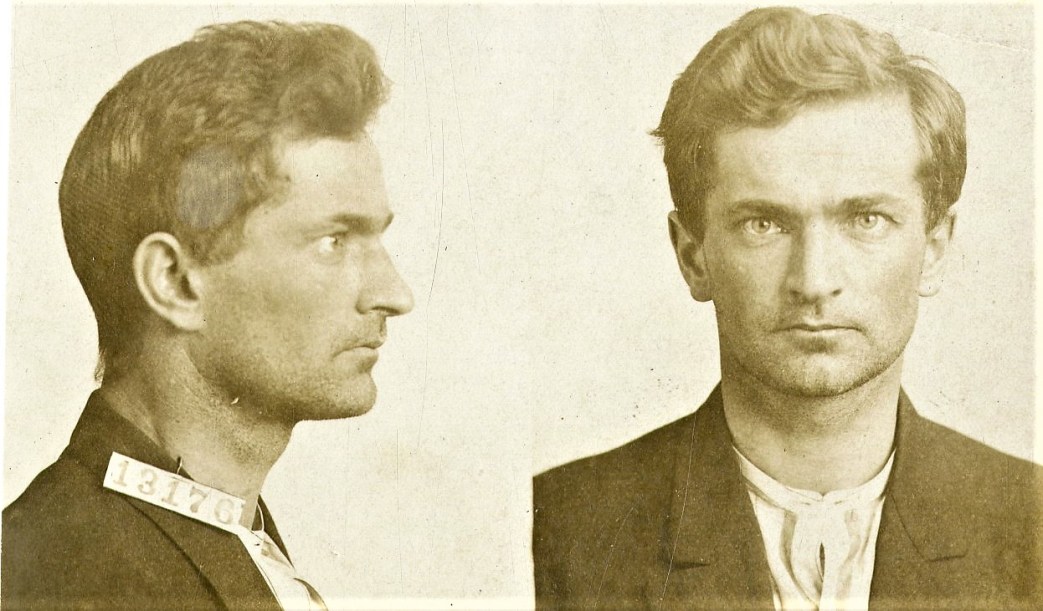

Wobbly Charles Plahn, serving ten years for syndicalist conspiracy, writes to One Big Union describing the brutal ‘isolation’ punishments meted out in Leavenworth to political prisoners in the aftermath a mess hall riot. Punishments that continue to be widespread and routine in the U.S.

‘Isolation at Leavenworth’ by Charles Plahn from One Big Union Monthly. Vol. 1 No. 10. December, 1919.

Much has been said about the treatment of the I.W.W. prisoners at Leavenworth. As I was one of the bunch that was thrown into the black hole on April 14th, 1919, and later placed in permanent “Isolation,” with six others, I will try to explain just what “Isolation” is.

Isolation was established a few years ago in the Federal Prison, according to the old timers, for the purpose of segregating the degenerates from the other inmates, but now it is being used for a punishment place.

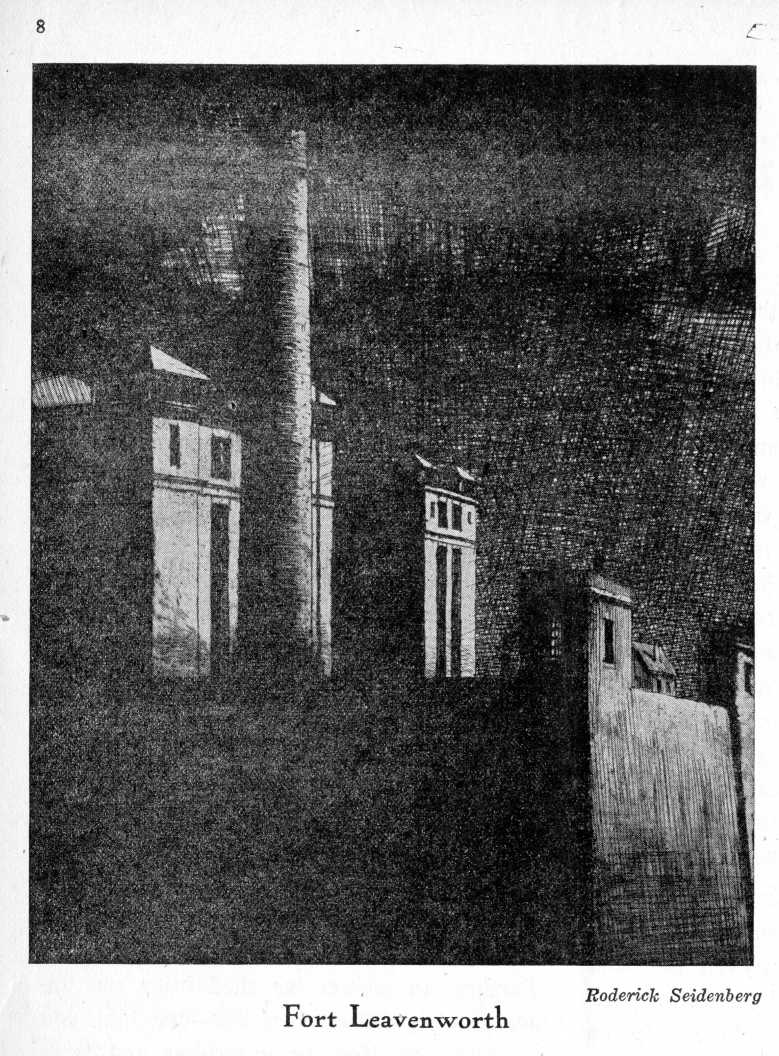

The building in which the isolation prisoners are kept is about 60×100 feet, the front being the office of the Deputy Warden, and the package room, where all packages are searched, before distribution among the prisoners. The rear of this building downstairs is the hole into which men are thrown for violating rules. There are 14 cells for this purpose, seven on each side of an eight-foot hallway. At the time of writing this article, six of these cells are occupied by men permanently isolated. The rest are commonly known to the inmates as “dry cells,” or the hole.

In this hole men are kept from three days up to ten or twelve days on bread and water. In each cell there is a very small window thru which the fresh air enters. This window is covered with a very heavy screen to prevent anyone on the outside from passing anything in to the prisoners. These cells are 8×22 and about 12 feet high. The bars of the door of the cells are also covered with heavy screens except on three of these cells. These three cells are used when men are “strung up”, as we call it, that is, chained to the bars during working hours and in some cases longer.

According to some of the old timers, men have been chained to the bars for days, being let down just long enough to answer nature’s calls. When a prisoner is “put on dry”, it means that his diet will consist of bread and water, about eight ounces of bread every twenty-four hours. There is no bed in these cells. There is nothing in the cell but a toilet and a wash bowl, a cup and a towel. In the evening there is a board, 3×6 ft. handed in with two thin blankets. This is the bed while “on dry.”

When a prisoner is reported by a guard, or a stool Pigeon, the deputy sends what is known as a “court call.” This court is held every morning at 8:30, regularly and also during the day when guards take a prisoner from his work direct to the deputy.

The deputy reads the charge, whatever it may be, and then usually says, “Well, what have you to say?” and if one is innocent, he usually denies the charge. In my experience with “courts calls,” the deputy always expressed himself in this manner.

“Well, I don’t want to do you any injustice. I will investigate this case. Put him in isolation,” meaning “on dry” from five to eight days. Before going on dry the guard in charge and his slugger, McNeal, a colored trustee in isolation, make the prisoner take off all his clothes. The clothes are then carefully searched for tobacco, as no tobacco is permitted while “on dry.” Then the prisoner is given a pair of overalls and jumper with the buttons cut off, so that when there are two or more men in one cell, they cannot cut off the buttons and use them to play checkers.

One is never told upon entering these dry cells how long he will be kept there, but the deputy comes around almost every day and looks in and asks, “Well, are you ready to do the right thing?” This meaning to become a stool or a snitch, for him. This is one way the deputy has of “getting” the men on dry; for if one refuses to do the “right thing,” as he calls it, he usually gets from five to eight days for minor offences.

In the spring of 1919 the food became so bad that there was a strong resentment shown by all inmates, The food was so bad and there was so little of it that many nights after a hard day’s work, one could not sleep for hunger. So, early in April there were two food riots. The last one, on Sunday April 13th, at supper time. That night all there was to eat ‘was sandy raisins and two slices of dry bread.

The mess hall seats about 1200 men and they all started shouting, “I’m hungry,” or “Give us some thing to eat,” to which there was no response. Plates were then thrown on the floor and a general rough house prevailed for at least 15 or 20 minutes when finally we were marched to our cells, without anything to eat.

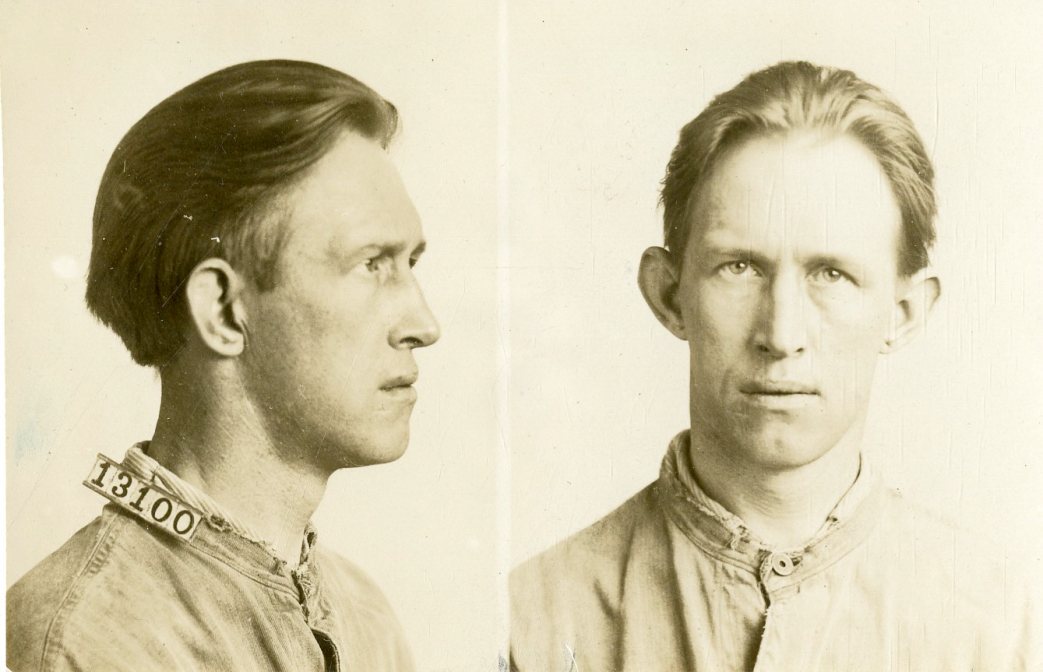

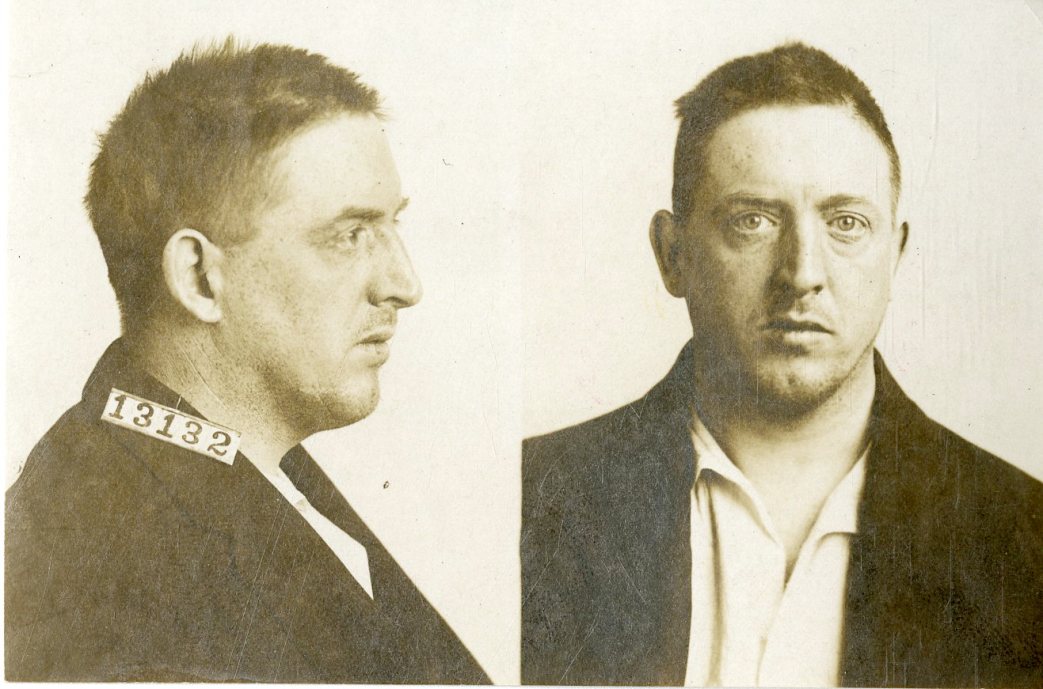

The next morning the deputy sent his runner for Jack Walsh, Bert Lorton, Edward Hamilton, Jack Jarvis, George Yager, Carl Ahlteen, William Weyh and myself, all members of the I.W.W. and one soldier, Robert McCurry, who by the way was an I.W.W. at heart and a mighty fine fellow. We were all charged by the deputy with inciting to riot in the mess hall the previous evening. I was also charged with throwing cups at the deputy for which he took one hundred days of my good time. We also were reduced to third grade, which takes away all privileges, such as writing, with the exception of one letter a month, library privileges, in fact all the minor comforts that first grade men have. We were all thrown in the “hole” as previously described, and were held for six days on bread and water.

Ahlteen and Weyh were released at this time, simply because there was not room for them in isolation and were permitted to go back to the big yard, but the rest of us were taken upstairs to permanent isolation, where we were given regular diet again and put to work, breaking rock about three hours per day.

There were about 12 other prisoners up-stairs who had been segregated as degenerates or for refusing to work. Among these were two white slavers who were the principal witnesses against Pete Pieri who was recently convicted on the frame-up charge by these two, in order that they might get a parole on the strength of their testimony.

Now we were kept here away from all the rest of the boys and all obstacles possible were placed in our way so as to keep us continually “in bad” to justify the action of the deputy. McNeal, the chief stool and slugger kept very busy, and many times we were forced into the hole for practically nothing. The guard in charge in the daytime is about eighty years old and has followed this work, according to his own statement, for twenty-five years and he seemed to delight in riding the wobblies whether on orders or otherwise, but he managed to keep some of us “on dry” all the time. Hamilton, being sickly, was thrown into the hole on several occasions for trying to get medical attention, the guard refusing to call up the hospital, thus forcing Hamilton to use the only means available, namely starting a “battleship,” or making noise enough to draw the attention of the captain or someone else outside.

Now I could go on and write about the various cases indefinitely, but I think this much will give the reader some idea of just what it means to be “isolated.” There are many isolated prisoners who go insane and are removed to Washington, D.C. to a government sanitarium.

Now I wish to call the readers attention to the fact that Bert Lorton, Jack Walsh, Edward Hamilton, of the Chicago case, and Caesar Tabib and Pete De Bernardi of the Sacramento case, and George Yager, a conscientious objector, are all still in permanent isolation. The first three mentioned are all serving ten years each and were sentenced to isolation by the Deputy Warden, L.J. Fletcher, for the rest of their time. All of these boys can receive letters, books, fruits, etc., but their writing privileges are limited.

Write these boys and tell your friends what they are going through. Try to raise bonds for them as well as for the rest of the boys. Imagine yourself in their places. They fought for you. Will you do the same for them? On with the drive for the release. of all Class War Prisoners.

One Big Union Monthly was a magazine published in Chicago by the General Executive Board of the Industrial Workers of the World from 1919 until 1938, with a break from February, 1921 until September, 1926 when Industrial Pioneer was produced. OBU was a large format, magazine publication with heavy use of images, cartoons and photos. OBU carried news, analysis, poetry, and art as well as I.W.W. local and national reports.

PDF of full issue: https://archive.org/download/sim_one-big-union-monthly_1919-12_1_10/sim_one-big-union-monthly_1919-12_1_10.pdf