‘Working-Women on Battle-Front Against Ignorance: A Moscow Experiment’ by Elkin from Soviet Russia (New York). Vol. 4 No. 15. April 9, 1921.

(The following is a translation from the December, 1920, issue of “Die Russische Korrespondenz” Berlin.)

When we approached the task of eradicating illiteracy, we found ourselves facing the fundamental question: what must be our goal in this matter? Shall we attempt to have all illiterates who are laborers learn only to read and to write, or must we simultaneously awaken class-consciousness in them, an understanding for the tasks of the hour, and arouse in them the spirit that battles for the new life—in a word, is not our most important task that of carrying on political propaganda by the side of elementary instruction? We had the latter point of view.

As a matter of fact, are reading and writing of predominating importance, when all is considered? The intelligentsia in all its parts has very much greater accomplishments than reading and writing. It can not only read and write, it is even learned, and yet its entire learning does not enable it to grasp the tremendous transformation that is at present in progress, and it is only little by little that the intelligentsia is taking its place by the side of the labor population. Writing and reading may be of service to the Red as well as to the White. For us it is important that reading and writing shall aid in placing the laboring population in the r of the pioneers for a new life. It is in this sense that we took up our task.

The first question that confronted us was: whom shall we give to the illiterates as teachers and organizers? The teachers who came from the ranks of the intellectuals can only teach reading and writing. They will very rarely go beyond this. We were quite clear that it would be necessary for us to make use in this work of the champions of Communism, the workers themselves. The war and the repeated mobilizations deprived us of the male workers, however, and therefore only one source remained from which we could draw our recruits —namely the working women. We began to draw them into this work. The sections of workingwomen at first responded rather weakly to the steps undertaken by us. They approved the plan with great misgivings. They were ready to make use of working-women as representatives in the commission in which they, almost always together with the men representatives, were to embody the “voice of the people.” But that was not what was wanted. We had to have the working-women themselves go about this work, themselves become organizers, propagandists, teachers.

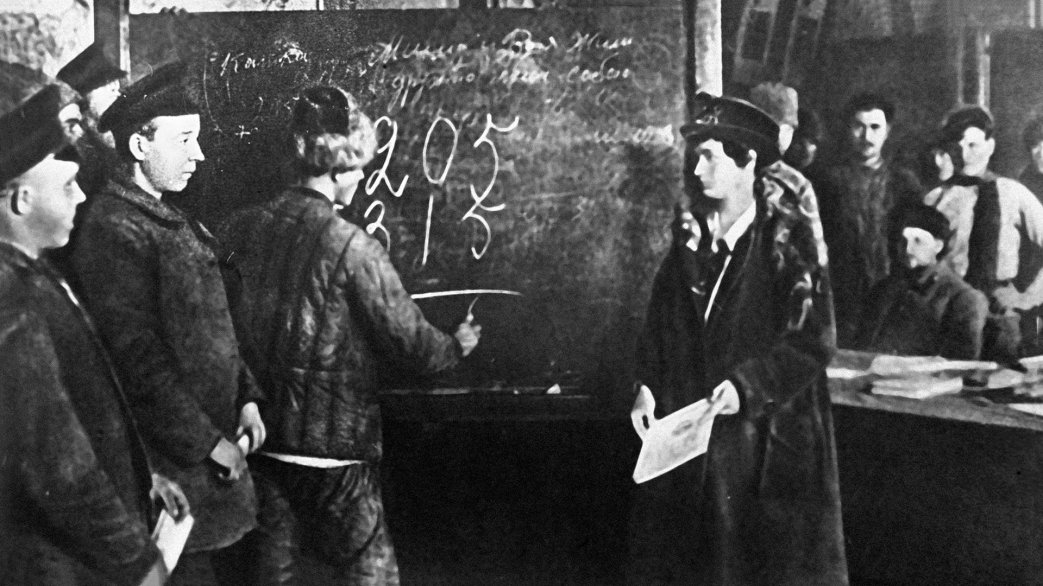

The working-women still felt themselves quite unfit for the work, and declined. They believed it would exceed their powers to work in the field of education. Many of them, furthermore, did not have a very good preliminary instruction, and thought that the women pupils, who were probably accustomed to the authority of the learned intellectuals, would laugh at their own teachers, if a woman with comparatively slight education, and one of their own comrade workers, should suddenly appear in place of the accustomed teacher. But these doubts were of short duration. The example given by the strong willed and courageous working-women carried all doubters along with it. Almost all the districts began to draw their teacher recruits from the sections of working-women and to open up weekly courses. After stopping work for the day, often still in their working aprons, the working-women hastened to their classes, attentively listened to the lectures, put questions, of course at first for the most part in a form, unlike that of the intelligentsia. They were interested in the question of how a woman with a young baby could be persuaded to attend school, of how a female speculator should be approached, of whether irregular attendance of the classes should be punished in any way, etc. It was easy to discern in these questions a profound understanding for their tasks, a grasp of the work on its practical side, a familiarity with the circles in question, and an ability to move them in the desired direction.

The work went on at great pressure. Workingwomen were active as organizers in 32 out of all the 52 district organizations of Moscow. In each district at least ten working-women were active teachers. Have they been able to discharge their tasks? This question may be answered in a decided affirmative. To be sure, the specialists who. work together with them frequently expressed themselves unfavorably on this question, but if this view of the specialists is checked up, it is possible to arrive at a different conclusion. The working-women have not the practised skill of a teacher from the spheres of the intelligentsia. Occasionally they are actually not able to answer this question or that. But they have something more valuable at their disposal than such universal knowledge. Their answer appears clearer and more homelike to the illiterate. They transmit to their pupils, the thirst for knowledge, the respect for education, the habit of approaching everything from the proletarian standpoint.

Has the fear that the illiterates would not accept them as their teachers been realized? No. The laboring masses are already accustomed to beholding workers at the head of the state, and this is becoming quite a customary experience with them. For more than half-a-year we have been working at Moscow, and certain conclusions can already be drawn. The expectations that we would be able, in a very short time, to teach tens of thousands of illiterates how to read and write in our schools have not been realized, for we did not take all the difficulties into consideration. It is possible that our forces were weaker than we at first believed. But we have been successful in another sense: we have won new forces and new champions, and now no one can still say that the attempt to make use of working-women for this task has proved a failure. The schools in which the working-women are active, are almost always full and completely adapted to the public life. We have new organizations recruited from the ranks of the workers, who have passed through our elementary schools, and who entered the schools as opponents of the Soviets and left them as devoted adherents of the Soviet idea and the cause of the workers.

When we were struggling in this manner to impart to the working men and women the necessary elementary knowledge, we were met with the objection that this was equivalent to a struggle against the intelligentsia. But this was not the case; it was a struggle for a new intelligentsia, and now we have this new intelligentsia, at least its vanguard, in the ranks of the working-women.

Soviet Russia began in the summer of 1919, published by the Bureau of Information of Soviet Russia and replaced The Weekly Bulletin of the Bureau of Information of Soviet Russia. In lieu of an Embassy the Russian Soviet Government Bureau was the official voice of the Soviets in the US. Soviet Russia was published as the official organ of the RSGB until February 1922 when Soviet Russia became to the official organ of The Friends of Soviet Russia, becoming Soviet Russia Pictorial in 1923. There is no better US-published source for information on the Soviet state at this time, and includes official statements, articles by prominent Bolsheviks, data on the Soviet economy, weekly reports on the wars for survival the Soviets were engaged in, as well as efforts to in the US to lift the blockade and begin trade with the emerging Soviet Union.

PDF of full issue: (large file): https://www.marxists.org/history/usa/pubs/srp/v3n09-aug-28-1920-soviet-russia.pdf