‘Churchill’s Bandit Career’ by Ralph Fox from the Daily Worker. Vol. 6 No. 24. April 3, 1929.

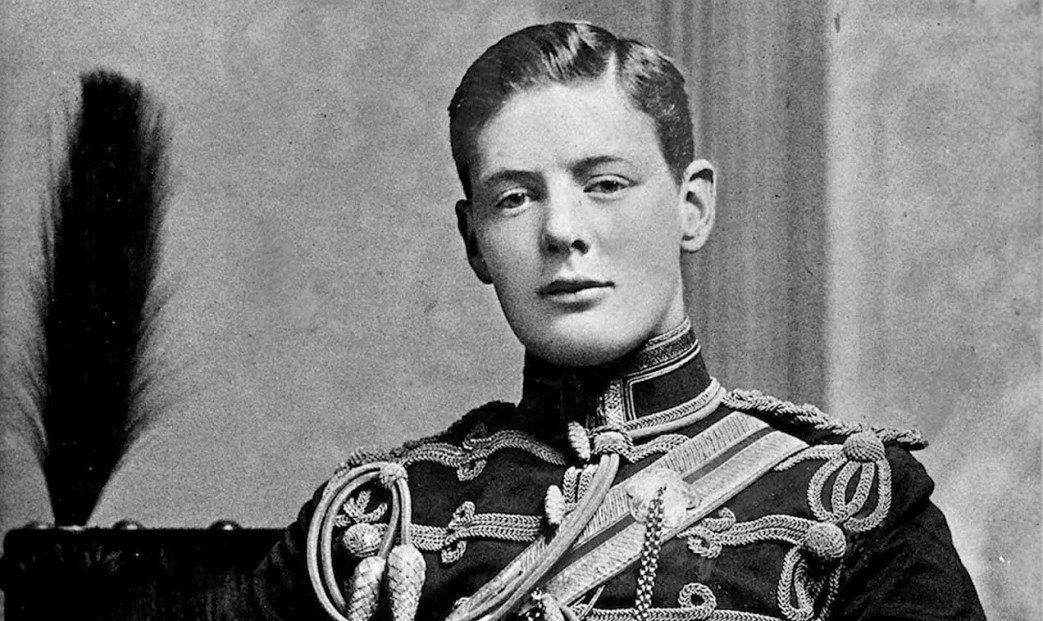

IN Winston Churchill, chancellor of the exchequer in the present government, we have a real bandit of power, the professional politician of capitalist democracy in its highest development. Churchill began his political life as a conservative. In 1901, speaking at a Tory meeting in Oxford, we find him describing the liberals in that exaggerated style of rhodomontade which has pervaded his speeches and “literary” works ever since.

“The Radical Party,” he informed a world that should have been horrified at the exposure, “is not dead…It is hiding from the public view like the toad in a block of coal. But when it stands forth in its hideousness the tories will have to hew the filthy object limb from limb.”

Alas, five years later the filthy object was the government, its limbs all sound, and the tories were dead. They remained dead for sixteen years, but Winston, having his own career at heart, was not with them. He joined the filthy object, and became home secretary in the Liberal government.

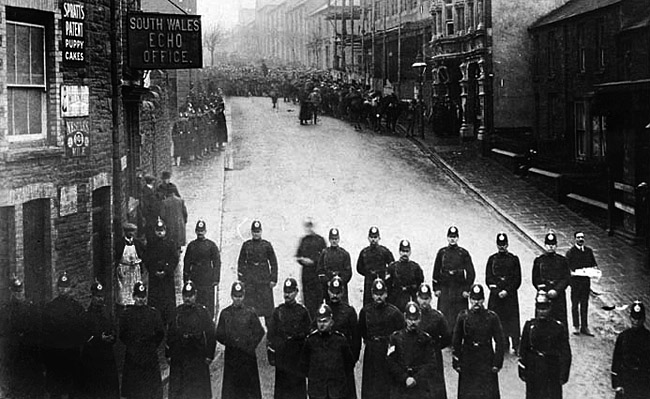

Troops Against Miners.

His record as a Liberal minister was an extraordinary one. In November, 1910, he filled the mining valleys of Rhondda, and Aberdare with police who violently broke up meetings of the striking miners, and when the miners protested sent in troops, who fired on the workers at Tonypandy. The following year he used troops as strikebreakers in the railway strike, and also against the dockers of Liverpool. His exploits with the guards in Sydney Street, when three anarchists defied the whole London garrison for a day, made him the laughing stock of the world.

The Tory government is at present claiming virtue for granting the franchise to women of 21. The mothers of these girls will remember Winston’s black record in the suffrage agitation before the war. In 1907 at Manchester, he declared he would never vote for a bill to enfranchise women on the same terms as men. Next year he was in favor of the franchise. By 1910 he was once more against it and voted against the Conciliation bill, having previously pledged himself to assist it.

But every woman remembers him most for the atrocity of Black Friday, November 18, 1910, when 300 women in groups of twelve tried to approach parliament. As the crowd were sympathetic, plain-clothes men mingled with them and acted as provocateurs, assaulting the women to give the impression of a hostile crowd. The home secretary’s orders were, “No arrests, but break up the demonstration.”

Plain-clothes men and uniformed police carried them out to the letter and the 300 women were shamefully beaten, stripped and tortured. Over one hundred were summoned for obstruction, but the police dared not call evidence, lest their savage attack be exposed, and the prosecution fell through. Lord Robert Cecil, challenging Churchill, said of this incident: “It is the duty of the police to arrest, not to beat the citizens of this country.”

This “Liberal,” on his “conversion” to the faith, declared at Glasgow in 1903, “War is fatal to Liberalism.” It proved to be almost the one true remark of his life. Yet, in 1914, he was the leader in the cabinet, as Lord Morley’s reminiscences revealed, of the “War at any price” party.

Churchill had always been a bold warrior. He was a soldier in the Soudan campaign and in the Malakand Expedition, a war correspondent in South Africa, who, the Boers alleged, broke his parole as a prisoner of war. In the “Great War,” as a full-fledged colonel of yeomanry, spurs and all, he went to France, but was swiftly “returned with thanks” by the soldiers on the spot. The battle of Sydney Street remained his high-water mark of active service under fire.

But as an arm-chair strategist he was more deadly. Antwerp and Gallipoli cost many thousand precious lives of British workers. Murmansk. Siberia, and the Caucasus accounted for thousands more in 1918-20.

Perhaps the revolution by which the Russian workers and peasants in November, 1917, gave their professional politicians “notice to quit” gave him his greatest chance. His hatred of the workers and their aspirations found full vent. His was the chief responsibility for sending British troops to Murmansk and the Caucasus.

In May, 1919, he told Kolchak’s envoy, General Golovin, when promising to strengthen the front with 10,000 men, “I am myself carrying out Admiral Kolchak’s orders.” Yet in March of the same year this man of no faith had declared that all British troops should be withdrawn from Archangel and Murmansk as soon as weather permitted.

Exposed by V. C.

In September he was exposed by one of his own class, Colonel Sherwood Kelly, V.C., who was sent home for refusing to command men any longer in a wicked, civil war. Colonel Kelly revealed that Churchill and General Ironside, G.O.C. at Murmansk, were even then planning operations on a 1,000 mile front. Kelly was court-martialed, but the troops had to be withdrawn nevertheless, partly because they were refusing to fight the Russian workers, partly because of the demand of the British workers that the war must stop and Soviet Russia be recognized.

But this was not his only plot against workers’ Russia. The same year found him plotting with the ex-terrorist Savinkov to set up a chain of “independent” states in South-East Russia and the Caucasus. These republics were referred to significantly enough as “oil states.” The plan has never been abandoned.

Churchill was forced to abandon military intervention, but never ceased his hatred of Russia. In 1920, during the Polish War, he wrote in the “Evening News,” “Peace with Russia is only another kind of war.” This has ever since been his policy, and he was one of those who must bear responsibility for the Arcos act of banditry and the breaking off of relations in 1927.

At the Alexandra Palace in June, 1926, he declared:— “Personally I hope I shall live to see the day when either there will be a civilized government in Russia, or that we shall have ended the present pretense of friendly relations.”

The second he saw a few months later. The “civilized” government he is still preparing for by war.

Churchill, however, is a man of changing mind. Even on Lenin and the Bolsheviks he has altered his opinion. In 1920 Lenin was “a monster on a pyramid of skulls” (“Evening News,” 14-6-20). In the “Times” of February 18, 1929, he writes of Lenin: “His mind was a remarkable instrument. When its light shone it revealed the whole world, its history, its sorrows, its stupidities, its shams, and, above all, its wrongs…The intellect was capacious and in some phases superb. A good husband, a gentle guest.”

His foul hatred of the Russian workers is only a phase of his general contempt and hatred for all toiling men and women. The man who used the soldiers at Tonypandy in 1910 was preparing to do the same again in 1919. As minister of war he issued a “Secret and Urgent” army circular to commanding officers in Great Britain. The terms of the circular were as follows:

“Will troops in your area assist in strikebreaking? Will they parade for draft to overseas, especially to Russia? Is there any growth of trade unionism among them? The effect outside trade unions have on them?” This circular, he explained, “was intended for use against the threatened railway strike.”

Miners will be interested to recall that on August 22, 1926, he declared in a speech at Westerham: “The government thought a better living could be got for the mining community on a basis of seven-and-a-half or eight hours than under the old seven-hour act.” Evidently the government still thinks so, in spite of semi-starvation in the mining areas and 300,000 unemployed miners.

The General Strike.

In the General Strike, “rushing about like a madman,” as H.G. Wells describes him, he filled the streets of London with soldiers, tanks and armored cars, commandeered the “Morning Post,” and produced from it by blackleg labor “The British Gazette,” which contained the most filthy stream of lies and abuse ever uttered against the British workers by their tear-ridden rulers.

When in 1928 the executive of the Amalgamated Union of Building Trade Workers accepted this man as a member, such a storm arose that the executive hastily met and informed him that he could not join the union.

Winston Churchill, political adventurer, military charlatan, enemy of the working class, His Majesty’s Chancellor of the Exchequer, is no doubt, in view of the immense revulsion against the Baldwin government, already considering whether or not he should join the Labor Party. For power is everything, opposition political death. With his former colleague, Lloyd George, he may yet be in a Labor cabinet, or a Labor-Liberal Coalition. He is not a man to accept political defeat, only extinction.

Ralph Winston Fox (1900–1936) was a British Communist, journalist, and historian. An early supporter of the Communist movement, Fox was a founding member of the British CP and traveled back and forth to the Soviet Union where he worked for the Comintern and wrote for the British Daily Worker. In 1929 he became a librarian at the Marx-Engels Institute in Moscow. Fox returned to England in 1932 and wrote several important works, including biographies of Lenin and Genghis Khan and a two volume-history, ‘The Class Struggle in Britain’. He joined the International Brigades in Spain, the XIV Brigade, as a Commissar. Only weeks later, in one of the Brigade’s first actions, Ralph Winston Fox was killed while fighting fascists at the Battle of Lopera along with fellow British Communist, the poet John Cornford in late December 1936.

The Daily Worker began in 1924 and was published in New York City by the Communist Party US and its predecessor organizations. Among the most long-lasting and important left publications in US history, it had a circulation of 35,000 at its peak. The Daily Worker came from The Ohio Socialist, published by the Left Wing-dominated Socialist Party of Ohio in Cleveland from 1917 to November 1919, when it became became The Toiler, paper of the Communist Labor Party. In December 1921 the above-ground Workers Party of America merged the Toiler with the paper Workers Council to found The Worker, which became The Daily Worker beginning January 13, 1924. National and City (New York and environs) editions exist

PDF of full issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/usa/pubs/dailyworker/1929/1929-ny/v06-n024-NY-apr-03-1929-DW-LOC.pdf