Frank Crosswaith details the beginnings of one of Black labor’s greatest struggles, the establishment of the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters led by A. Philip Randolph launched in 1925.

‘Porters Smash a Company Union’ by Frank R. Crosswaith from Labor Age. Vol. 17 No. 1. January, 1928.

Show Down Approaches

ANOTHER year has ended and the two-year-old A Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters still stands defiantly ignoring the dire prediction of its foes, and gradually but surely realizing the hopes of its friends. When the Pullman porters launched their never-to-be-forgotten crusade against the “Company Union” of the Pullman Company many cynics of both races, saw in the attempt “a foolish gamble,” “a waste of time and money;” “just another hopeless effort on the part of the American Negro to enter the field of trade union organization;” “the Pullman Company is too powerful a foe.”

In spite of these voices of skepticism and defeatism ringing in our ears we solemnly resolved that no matter what the cost might be in blood or money we would not become discouraged and surrender, but would fight on in such a fashion as to convince even these skeptics that what other races had done any race could do, and that the Negro worker had a worthwhile contribution to make toward the cause of Labor’s emancipation. Encouraged by the sympathy and support of our numerous friends we have made good; more than that, we have surpassed the rosiest hopes entertained for us by our supporters.

A Necessary Technique

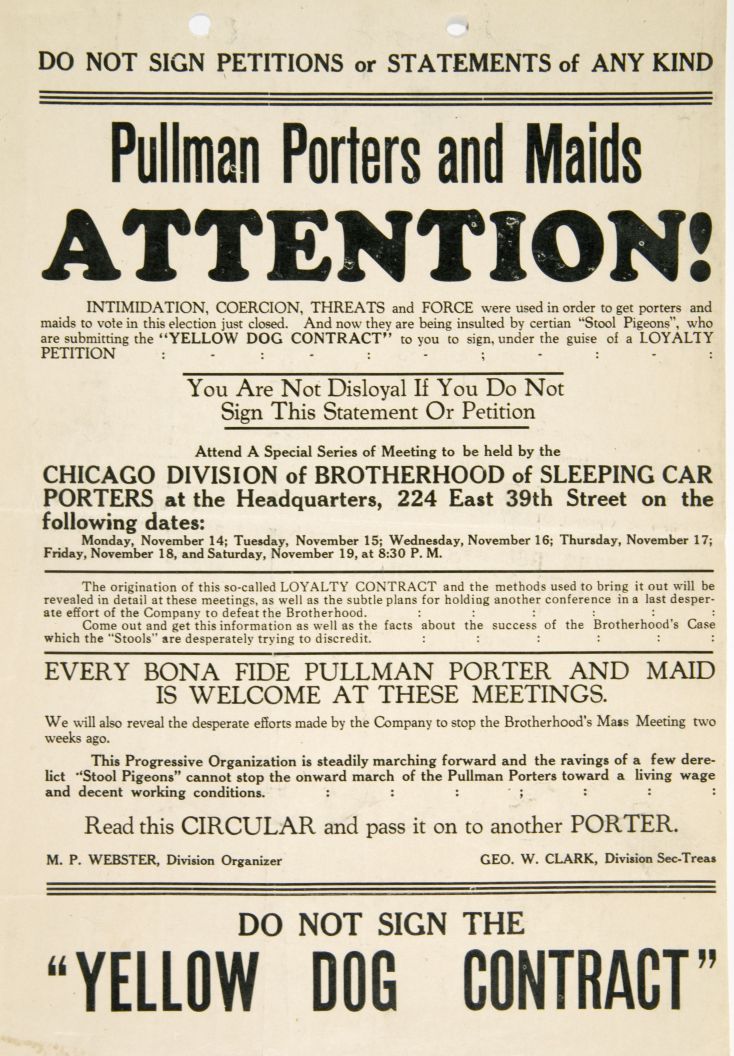

Organized labor can be proud of the fact that at least one of the most powerful Company Unions in the United States has practically been destroyed. In bringing about this result the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters has set a new pace and introduced a new technique in the field of trade union organization. Thirteen months after the bugle call of organization was sounded, a majority of the porters and maids in the employ of the Pullman Company was enrolled in the Brotherhood, to the amazement of all concerned; this feat was accomplished by methods closely akin to the underground railroad of slavery fame. The members of the organization could not be permitted to publicly declare themselves as belonging to the Brotherhood: for, the Company would penalize them, as it actually did to a number whose identity was disclosed because of their own inability to hide the fact and be silent.

Some of the most trusted men in the Pullman service are affiliated with the Brotherhood while continuing to enjoy the confidence and good graces of Pullman officials. The remarkable agility and ease with which these Brotherhood men can adjust themselves and hoodwink a Pullman official is traceable to the fact that conditions during slavery compelled the Negro to resort to this ordinarily despicable practice of duplicity in order to escape some of the hardships that were inevitable parts of the institution of Chattel slavery. The Negro learned his lesson well and the Pullman porter has forgotten none of it. Recently the Pullman Company gave a banquet to a carefully selected group of “trusted and faithful porters.” At this banquet resolutions were adopted attacking the Brotherhood and repudiating the efforts of the organization to abolish tipping as the method by which porters are rewarded for their labor. Those who selected these men thought surely they had chosen a group antagonistic to the union; nevertheless, of the forty or more who attended, eleven were members in good standing of the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters; and twenty-five minutes after the banquet was over the officers of the Brotherhood had a complete report of what happened, and affidavits were later sworn to by these porters repudiating what they had done at the banquet. This example is typical of a nationwide condition, of which it is safe to say that the Pullman Company cannot call together three Pullman porters in any of its districts without including one er more members of the union. In the recent elections held by the Company under the so-called Employee Representation Plan, members of the union were in several instances functioning on the election Committee so-called.

Songbirds of Cowardice

When the movement to organize the porters was launched, a chorus of Negro voices especially was raised everywhere advising the porters not to organize; “to let well enough alone,” that “the Pullman Company was the Negroes’ best friend,” since it employed more Negroes than any other corporation in the United States, and that to organize would be an indication of ingratitude.

Some of these songbirds of cowardice and defeatism pretended to be a little more intelligent than the others and found what they called “real reasons” why the porters should not organize. “If the porters organized, the Company would retaliate by discharging all its Negro porters and replacing them with white ones,” they harmonized.

If the Pullman Company did replace its Negro porters with white ones, it is safe to say that within a comparatively short period of time these white porters would get together and present the Company with a formidable trade union organization, and since the Company is interested primarily not in the color of those whom it exploits, but in the willingness and extent of its workers to be exploited it can readily be seen that the Company’s best self-interest is the most eloquent and persuasive argument against this alleged “real reason.”

Notwithstanding the many efforts to persuade the porters against organization, the men continued to enroll in the Brotherhood to such an extent that shortly after the first call to organization was issued by A. Philip Randolph, the movement took on the aspect of a genuine crusade; a majority of the porters and maids were enrolled in the organization, and the Brotherhood was thereby duly qualified to present the porters’ grievances before the United States Board of Mediation. After an extensive and complete investigation, the Board recommended arbitration, which the Pullman Company unblushingly declined, but which was accepted by the Brotherhood. This recommendation of the Board was a signal victory, in that it carried with it recognition of the Brotherhood as the legitimate representative of the porters and maids, and by the same token gave to it the same status as enjoyed by the other railroad labor organizations.

Under the law governing disputes between transportation workers and their employers (the Watson-Parker Law), the next step of the Brotherhood is to create an emergency which will warrant the appointment of “an Emergency Board” by the President of the United States. Plans for this phase of the porters’ struggle are now being meticulously laid.

In conjunction with, but independent of this action, the Brotherhood petitioned the Interstate Commerce Commission for an investigation of the finances of the Pullman Company, as they relate to the wages of the porters, to tips and the traveling public. The Pullman Company in answer to this petition, outrightly challenged the right of the I.C.C. to entertain the porters petition on the ground that the questions involved were without the jurisdiction of the I.C.C. The Commission, however, over-ruled the contention of the Company and has set a date (January 11, 1928 at Washington, D.C.) when the attorneys of the Pullman Company and the Brotherhood will appear before it and argue first, the question of jurisdiction then the subject matter of the porters petition.

Tips

It is the contention of the Brotherhood that since Pullman porters are required by the Pullman Company to depend upon tips in order to bring their income within a reasonable distance of what is considered a living wage, and since tips are uncertain, voluntary and inadequate, this custom tends to inculcate and foster discrimination in the kind and degree of service the porters render the traveling public. For instance, two travelers starting from the same point to a common destination must pay the same price for their Pullman tickets and are, therefore, equally entitled to all the services the Pullman Company is capable of rendering through its representative, the Pullman porter. Said porter knows the two travelers, having had them in his car on previous occasions. He knows that “A” will give him 25 cents when the trip is completed, and that “B” will give him only 10 cents. Fore-armed with this knowledge, the porter will without a doubt give to “A” better and more service than he gives to “B,” although they are both entitled to equal service and equal treatment. To expect otherwise from the porter is to indicate a complete lack of understanding of human nature.

A second contention of the Brotherhood is that the Pullman porter is more than a servant of the Pullman Company. He is a public servant, health officer, policeman, etc. And since he must depend upon tips in lieu of wages, he is made an easy victim to bribery from passengers violating or desirous of violating any of the laws which the porter is supposed to uphold.

The wage of a Pullman porter is $72.50 per month; his hours are approximately. 400, calculated upon an 11,000 mileage basis. He has practically no opportunities for advancement. “Once a porter always one,” sums up the destiny of a pullman porter, except those who are selected by the management to serve under the high-sounding title of welfare worker or instructor, but whose title has but little, if anything, to do with the job assigned them. They are chosen among the porters for the same purpose and in the same manner that the master used to select certain slaves from among the gang. He would give them a smile now and then, an old coat once in a while, and, on the whole, a trifle more inconsequential consideration, and in return the “chosen few” snooped, spied and lied to the master about their fellow slaves.

The demands of the Brotherhood include a 240 hour work month, the abolition of tips as reward for the porter’s work and the substitution of $150 per month therefor.

In their struggle to effect organization, the Pullman porters not alone essayed to lock horns with one of the most powerful aggregations of capital in the United States, but also threw down the gauntlet to a well-entrenched “company union,” euphemistically called “The Employee Representation Plan,” under which the porters have been working and chafing for over five years. It is safe to state that the successful struggle waged against the Pullman “Company Union,” is the first instance in the history of the American Labor Movement when such a mighty one of these obnoxious product of “a war to make the world safe for democracy” has been completely overcome and wrecked.

Boycotting A Newspaper One of the most startling achievements of the Brotherhood, however, is not generally known, yet is of singular significance both to the Negro and organized labor.

Among the voices of opposition to the Brotherhood was that of the Chicago Defender, by far the largest and among the most influential Negro newspapers in the world with a circulation of about a quarter of a million copies per week. Early in the struggle the porters recognized it as the mouthpiece of the Pullman Company and their most formidable opponent. Copies of the paper were from time to time given to the porters by the Company. To overcome The Defender was one of the problems confronting the organizers of the Brotherhood. However, the men themselves, uninstructed, organized a boycott of the paper which became so effective and successful that its circulation steadily dropped until it reached an alarmingly low figure.

Negroes other than Pullman porters also joined in the unofficial boycott and the paper, once the journalistic pride of the race, became the most despised. About a year ago, the Chicago Defender saw the error of its ways and came out boldly and unreservedly championing the cause of the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters. This is probably the first time that the Negro has engaged in a boycott and his remarkable success indicative of the potential power of the race along this line, and which may yet be most effectively used to right some of the many wrongs inflicted upon him, particularly in the Southland.

PDF of full issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/usa/pubs/laborage/v17n01-jan-1928-LA.pdf