Transcribed online for the first here, the sixth and final chapter of the 1925 International Publishers edition Kautsky’s 1908 ‘Foundations of Christianity’ in which he looks at Engels’ late thoughts on the subject and Christianity’s fate under modern Socialism.

‘Christianity and Socialism’ (1908) by Karl Kautsky from Foundations of Christianity. International Publishers, New York. 1925.

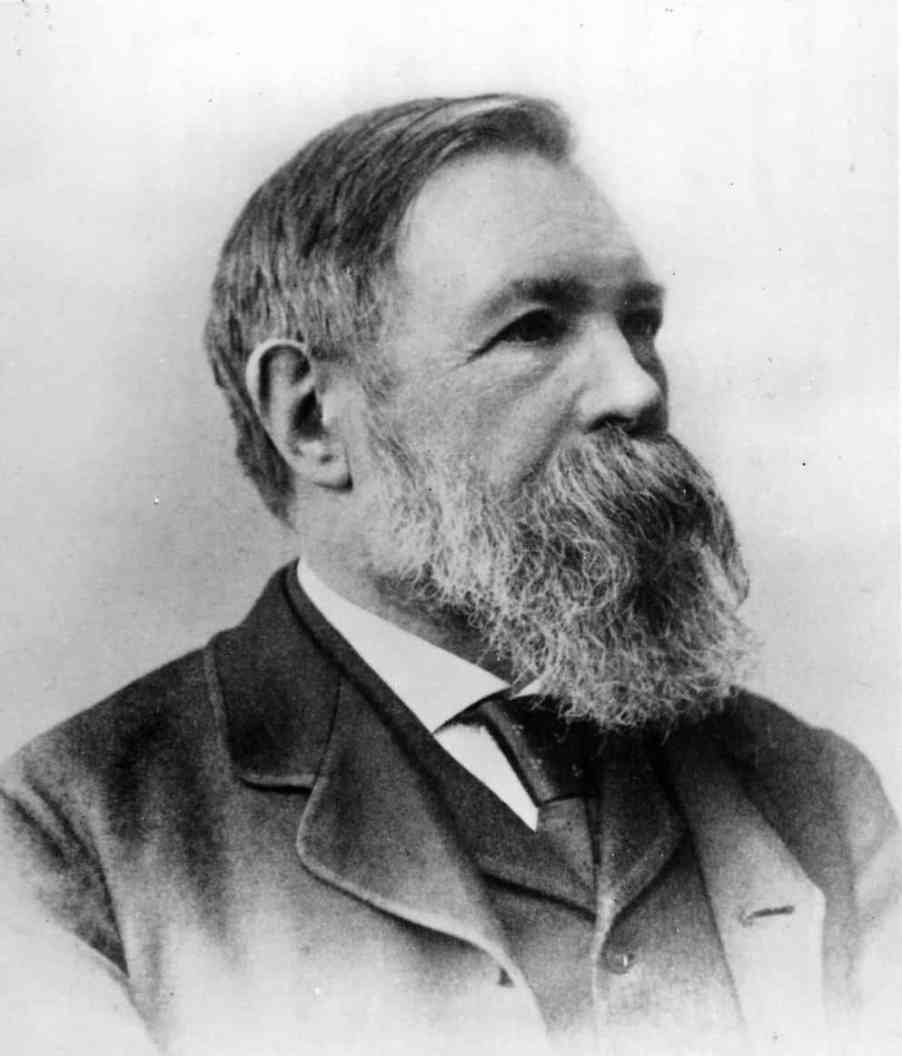

THE famous introduction written by Engels in March, 1895, for the new edition of Marx’s Class Struggles in France from 1848 to 1850 closes with the following words:

“Now almost sixteen hundred years ago, there was at work in the Roman Empire a dangerous revolutionary party. It undermined religion and all the foundations of the State; it denied pointblank that the emperor’s will was the highest law; it was without a fatherland, international; it spread out over the entire realm from Gaul to Asia, and even beyond the borders of the Empire. It had long worked underground and in secrecy, but had, for some time, felt strong enough to come out openly in the light of day. This revolutionary party, known under the name of Christians, also had a strong representation in the army; entire legions were composed of Christians. When they were commanded to attend the sacrificial ceremonies of the Pagan established church, there to serve as a guard of honor, the revolutionary soldiers went so far in their insolence as to fasten special symbols—crosses—on their helmets. The customary disciplinary barrack measures of their officers proved fruitless. The emperor, Diocletian, could no longer quietly look on and see how order, obedience and discipline were undermined in his army. He promulgated an anti-Socialist—beg pardon—an anti-Christian law. The meetings of the revolutionaries were prohibited, their meeting places were closed or even demolished, the Christian symbols, crosses, etc., were forbidden as in Saxony they forbid red pocket handkerchiefs. The Christians were declared unfit to hold office in the State, they could not even become corporals. Inasmuch as at that time they did not have judges well drilled as to the ‘reputation of a person’, such as Herr Koller’s anti-Socialist law presupposes, the Christians were simply forbidden to seek their rights in a court of law. But this exceptional law, too, remained ineffective. In defiance, the Christians tore it from the walls, yea, it is said that at Nicomedia they fired the emperor’s palace over his head. Then the latter revenged himself by means of a great persecution of Christians in 303 A.D. This was the last persecution of its kind. It was so effective that, seventeen years later, the army was composed largely of Christians, and that the next autocratic ruler of the entire Roman Empire, Constantine, called ‘the Great’ by the clericals, proclaimed Christianity as the religion of the State.” *1

He who knows his Engels and compares these last lines of Engels’s “political testament” with the views Engels expressed throughout his life, cannot have any doubts as to the intentions behind this humorous comparison. Engels wanted to point out the irresistible and elemental nature of the progress of our movement, which he said owed its inevitability particularly to the increase of its adherents in the army, so that it would soon be able to force even the most powerful autocrat to yield.

This narration is interesting chiefly as an expression of the healthy optimism which Engels retained up to his death.

But the passage also has been interpreted differently, since it is preceded by statements to the effect that the party at present flourishes best when pursuing legal methods. Certain persons have maintained that Engels in his “political testament” denies his entire life-work and finally represents the revolutionary standpoint, which he has defended for two generations, as an error. These persons inferred that Engels had now recognized Marx’s doctrine—to the effect that force is the midwife of every new form of society—as no longer tenable. In drawing a comparison between Christianity and Socialism, interpreters of this stamp did not place the emphasis on the irresistible and elemental nature of the advance, but on Constantine’s voluntary proclamation of Christianity as the state religion; the latter was brought to victory without any violent convulsions in the state, by peaceful means alone, through the friendly assistance of the government.

These persons imagine that Socialism will also conquer thus Immediately after the death of Engels this hope indeed seemed about to be fulfilled, as M. Waldeck-Rousseau came out as a new Constantine in France and appointed a Bishop of the new Christians, M. Millerand, as his Minister.

He who knows Engels and judges him without bias, will know that it never even entered Engels’s mind to abjure his revolutionary ideas, that the final passage of his introduction cannot therefore be interpreted in the sense indicated above. But it must be admitted that the passage is not very clear. Persons who do not know Engels, who imagine that he was assailed immediately before his death by sudden doubts as to the utility of his entire life-work, may interpret this passage, standing alone, as indicating that Christianity’s path to victory is a pattern for the journey that Socialism has still to make.

If this had really been Engels’s opinion, no worse judgment could have been spoken on Socialism; it would have been equivalent to a prophecy not of approaching triumph, but of a complete defeat of the great goal proposed by Socialism.

It is characteristic that the persons who thus utilize this passage overlook all the great and profound elements in Engels, but greet with enthusiasm such sentences as—1if they really contained what is alleged to be in them—would be entirely erroneous.

We have seen that Christianity did not attain victory until it had been transformed into the precise opposite of its original character; that the victory of Christianity was not the victory of the proletariat, but of the clergy which was exploiting and dominating the proletariat; that Christianity was not victorious as a subversive force, but as a conservative force, as a new prop of suppression and exploitation; that it not only did not eliminate the imperial power, slavery, the poverty of the masses, and the concentration of wealth in a few hands, but perpetuated these conditions. The Christian organization, the Church, attained victory by surrendering its original aims and defending their opposite.

Indeed, if the victory of Socialism is to be achieved in the same way as that of Christianity, this would be a good reason for renouncing, not revolution, but the Social-Democracy; no severer accusation could be raised against the Social-Democracy, from the proletarian standpoint, and the attacks made by the anarchists against the Social-Democracy would be only too well justified. Indeed, the attempt by bourgeois and socialistic elements at a socialistic ministerial function in France, which aimed to imitate the Christian method of rendering Christianity a state institution in the old days—and applied, strangely enough, in this instance, to combat the State Church—has had no other effect than to strengthen the semi-anarchistic, anti-socialistic syndicalism.

But fortunately the parallel between Christianity and Socialism is completely out of place in this connection. Christianity, to be sure, is in its origin a movement of the poor, like Socialism, and both therefore have many elements in common, as we have had occasion to point out.

Engels also referred to this similarity in an article entitled “On the History of Primitive Christianity,” in Die Neue Zeit,*2 written shortly before his death, and indicating how profoundly Engels was interested in this subject at that time, how natural it therefore was for him to write the parallel found in his introduction to the Class Struggles in France. This article says:

“The history of primitive Christianity presents remarkable coincidences with the modern workers’ movement. Like the latter, Christianity was originally a movement of the oppressed; it first appeared as a religion of slaves and freedmen, of the poor, the outcasts, of the peoples subjected or dispersed by Rome. Both Christianity and Socialism preach an approaching redemption from servitude and misery; Christianity assigns this redemption to a future life in Heaven after death; Socialism would attain it in this world by a transformation of society. Both are hunted and persecuted, their adherents outlawed, subjected to special legislation, represented, in the one case, as enemies of the human race, in the other, as enemies of the nation, religion, the family, of the social order. And in spite of all persecutions, in some cases even aided to victory by such persecutions, both advance irresistibly. Three centuries after its beginning, Christianity is the recognized state religion of the Roman Empire, and in barely sixty years Socialism has conquered a place that renders its victory absolutely certain.”

This parallel is correct on the whole, with a few limitations of course; Christianity can hardly be called a religion of the slaves; it did nothing for them. On the other hand, the liberation from misery proclaimed by Christianity was at first quite material, to be realized on this earth, not in Heaven. This latter circumstance, however, increases the similarity with the modern workers’ movement. Engels continues:

“The parallel between these two historical phenomena becomes apparent even in the Middle Ages, in the first insurrections of oppressed peasants, and particularly of urban plebeians. .. . The communists of the French Revolution, as well as Weitling and his adherents, make references to primitive Christianity long before Ernest Renan said: ‘If you would form an idea of the first Christian congregations drop in at the local section of the International Workers’ Association.

“The French litterateur who wrote the ecclesiastical novel Les Origines du Christianisme, a plagiarism of German Bible criticism unparalleled for its audacity—was himself not aware how much truth these words contained. I should like to see any old ‘international’ who would read, let us say, the so-called Second Epistle to the Corinthians, without feeling the opening of old wounds at least in a certain sense.”

Engels then goes into greater detail in comparing primitive Christianity and the International, but he does not trace the later development of either Christianity or the workers’ movement. The dialectic collapse of the former does not receive his attention, and yet, if Engels had pursued this subject, he would have discovered traces of similar transformations in the modern workers’ movement. Like Christianity, this movement is obliged to create permanent organs in the course of its growth, a sort of professional bureaucracy in the party, as well as in the unions, without which it cannot function, which are a necessity for it, which must continue to grow, and obtain more and more important duties.

This bureaucracy—which must be taken in the broad sense as including not only the administrative officials, but also editors and parliamentary delegates—will not this bureaucracy in the course of things become a new aristocracy, like the clergy headed by the bishop? Will it not become an aristocracy dominating and exploiting the working masses and finally attaining the power to deal with the state authorities on equal terms, thus being tempted not to overthrow them but join them?

This final outcome would be certain if the parallel were perfect. But fortunately this is not the case. In spite of the numerous similarities between Christianity and the modern workers’ movement, there are also fundamental differences.

Particularly, the proletariat today is quite different from the proletariat of early Christianity. The traditional view of a free proletariat consisting of beggars only is probably exaggerated; the slaves were not the only workers. But it is true that slave labor also corrupted the free working proletarians, most of whom worked in their own homes. A laboring proletarian’s ideal then strove, as did that of the beggar, to realize an existence without labor at the expense of the rich, who were expected to squeeze the necessary quantity of products out of the slaves.

Furthermore, Christianity in the first three centuries was exclusively an urban movement, but the city proletarians at that time had but little significance in the composition of society, whose productive basis was almost entirely that of antiquity, combined with quite important industrial operations.

As a result of all this, the chief bearers of the Christian movement, the free urban proletarians, workers and idlers, did not feel that society was living on them; they all strove to live on society without giving any return. Work played no part in their vision of the future state.

It was therefore of course natural that in spite of all the class hatred against the rich, the effort to gain their favor and their generosity becomes apparent again and again, and the inclination of the ecclesiastical bureaucracy to favor the rich members in the mass of the congregation encountered as little resistance as did the arrogance of this bureaucracy itself.

The economic and moral decay of the proletariat in the Roman Empire was further increased by the general decline of all society, which was becoming poorer and more desperate, while its productive forces were declining more and more. Thus hopelessness and despair seized all classes, crippled their initiative, caused all to expect salvation only at the hands of extraordinary and supernatural powers, made them helpless victims of any clever impostor, or of any energetic, self-confident adventurer, caused them to relinquish as hopeless any independent resistance to any of the dominant powers.

How different is the modern proletariat! It is a proletariat of labor, and it knows that all society rests upon its shoulders. And the capitalistic mode of production is shifting the center of gravity in production more and more from the provinces to the industrial centers, in which mental and political life are most active. The workers of these centers, the most energetic and intelligent of all, now become the elements controlling the destinies of society.

Simultaneously, the dominant mode of production enhances the productive forces enormously and thus increases the claims made on society by the workers, also increasing their power to put through these claims. Hopefulness, confidence, self-consciousness, inspire them, as they once inspired the rising bourgeoisie, giving it the power to break the chains of the feudal, ecclesiastical, bureaucratic domination and exploitation, and drawing the necessary strength from the great growth of capital.

The origin of Christianity coincides with a collapse of democracy. The three centuries of its development previous to its recognition are characterized by a constant decline of all remnants of autonomy, and also by a progressive disintegration of the productive forces.

The modern workers’ movement originates in an immense victory of democracy, namely, the great French Revolution. The century that has elapsed since then, with all its changes and fluctuations, nevertheless presents a steady advance of democracy, a veritably fabulous increase in the productive forces, and not only a greater expansion, but also a greater independence and clarity on the part of the proletariat.

One has only to examine this contrast to become aware that the development of Socialism cannot possibly deviate from its course as did that of Christianity; we need not fear that it will develop a new Class of rulers and exploiters from its ranks, sharing their booty with the old tyrants.

While the fighting ability and the fighting spirit of the proletariat progressively decreased in the Roman Empire, these qualities are being strengthened in modern society; the class oppositions are becoming perceptibly more acute, and this alone must frustrate all attempts to induce the proletariat to relinquish its struggle because its champions have been favored. Any such attempts have hitherto led to the isolation of the person making them, who has been deserted by the proletariat in spite of his former services to them. But not only the proletariat and the political and social environment in which it moves are entirely different today from the conditions of the primitive Christian era; present-day communism and the conditions of its realization are quite different from the conditions of ancient communism.

The struggle for communism, the need for communism, today originate from the same source, namely poverty, and so long as Socialism is only a Socialism of the feelings, only an expression of this want, it will occasionally express itself even in the modern workers’ movement in tendencies resembling those of the time of primitive Christianity. The slightest understanding of the economic conditions of present-day communism will at once recognize how different it is from the primitive Christian communism.

The concentration of wealth in a few hands, which in the Roman Empire proceeded hand in hand with a constant decrease in the productive forces—for which decrease it was partly responsible—this same concentration has today become the basis for an enormous increase in productive forces. While the distribution of wealth then did not injure the productivity of society in the slightest degree, but rather favored it, it would be equivalent to a complete crippling of production today. Modern communism can no longer think of an equal distribution of wealth; its object is rather to secure the greatest possible increase in the productivity of labor and a more equitable distribution of the annual products of labor by pushing the concentration of wealth to the highest point, transforming it from the private monopoly of a few capitalist groups into a state monopoly.

But modern communism, if it would satisfy the needs of the new man created by modern methods of production, must also fully preserve individualism of consumption. This individualism does not involve an isolation of individuals from each other when consuming; it may even take the form of a social consumption, of social activity; the individualism of enjoyment is not equivalent to an abolition of large enterprises in the production of articles of consumption, nor to a displacement of the machine by hand labor, as many esthetic Socialists may dream. But the individualism of consumption requires liberty in the choice of enjoyments, also liberty in the choice of the society in which the consumer consumes.

But the mass of the urban population in primitive Christian days knew no forms of social production; large enterprises with free workers can hardly be said to have existed in urban industry. But they are well acquainted with social forms of consumption; particularly common meals, often provided by the congregation or the state.

Thus the primitive Christian communism was a communism of distribution of wealth and standardization of consumption; modern communism means concentration of wealth and concentration of production.

The primitive Christian communism did not need to be extended over all of society in order to be brought about. Its execution could begin within a limited area, in fact, it might, within those limits, assume permanent forms; indeed, the latter were of a nature that precluded their becoming a universal form of society.

Therefore primitive Christian communism necessarily became a new form of aristocracy, and it was obliged to accomplish this inner dialectic even within society as it then was. It could not abolish classes, but only add a new form of domination to society.

But modern communism, in view of the immense expansion of the means of production, the social character of the mode of production, the far-reaching concentration of the most important objects of wealth, has not the slightest chance of being brought about on any smaller scale than that of society as a whole. All attempts to realize communism in the petty establishments of socialistic colonies or productive cooperatives within society as it is, have been failures. Communism may not be produced by the formation of little organizations within capitalist society, which would gradually absorb that society as they expand, but only by the attainment of a power sufficient to control and transform the whole of social life. This power is the state power. The conquest of political power by the proletariat is the first condition of the realization of modern communism.

Until the proletariat reaches this stage, there can be no thought of socialistic production, or of the latter’s effecting contradictions in its development that will transform sense into nonsense and benefactions into torments.*3 But even after the modern proletariat has conquered the political power, social production will not come into being at once as a finished whole, but economic development will suddenly take a new turn, no longer in the direction of an accentuation of capitalism but toward the development of a social production. When will the latter have advanced to the point where contradictions and abuses will appear in it, destined to develop the new society in another direction now unknown and absolutely obscure? This condition cannot be outlined at present and need not be dwelt on here.

As far as we can trace the modern socialistic movement, it is impossible for it to produce phenomena that will show any similarity with those of Christianity as a state religion. But it is also true that the manner in which Christianity attained its victory cannot in any way serve as a pattern for the modern movement of proletarian ambitions.

The victory of the leaders of the proletariat will surely not be as easy as that of the good bishops of the Fourth Century.

But we may maintain not only that Socialism will not develop any internal contradictions in the period preceding this victory, that will be comparable with those attending the last phases of Christianity, but also that no such contradictions will materialize in the period in which the predictable consequences of this victory are developed.

For capitalism has developed the conditions for placing society on an entirely new basis, completely different from all of the bases on which society has stood since class distinctions first arose. While no new revolutionary class or party—even those that went much further than Christianity in the form recognized by Constantine, even when they actually would abolish existing class distinctions—has ever been able to abolish all classes, but has always substituted new class distinctions for the old ones, we now have the material conditions for an elimination of all class distinctions. The modern proletariat is moved by its class interest to utilize these conditions in the direction of this abolition, for it is now the lowest class, while in the days of Christianity the slaves were lower than the proletariat.

Class differences and class oppositions ought by no means to be confused with the distinctions brought about between the various callings, by a division of labor. The contrast between classes is the result of three causes: private property in the means of production, in the manipulation of weapons, in science. Certain technical and social conditions produce the differentiation between those who possess the means of production and those who do not; later, they produce the distinction between those who are trained in the use of arms and those who are defenseless; finally comes the distinction between those well versed in science and those who are ignorant.

The capitalistic mode of production creates the necessary conditions for abolishing all these oppositions. It not only works toward an abolition of private property in the means of production, but by its wealth of productive forces it also abolishes the necessity of limiting military training and knowledge to certain strata. This necessity had been created as soon as military training and science had attained a rather high stage, enabling those who had free time and material means exceeding the needs of life, to acquire weapons and knowledge and to apply both successfully.

While the productivity of labor remained small and yielded but a slight surplus, not everyone was able to gain sufficient time and means to keep abreast of the military knowledge or the general science of his day. In fact, the surplus of many individuals was required to enable a single individual to make a perfect performance in the military or learned field.

This could not be obtained except by the exploitation of many by a few. The increased intelligence and military ability of the few enabled them to oppress and exploit the defenseless ignorant mass. On the other hand, precisely the oppression and exploitation of the mass became the means of increasing the military skill and the knowledge of the ruling classes.

Nations that were able to remain free from exploitation and oppression remained ignorant and often defenseless, as opposed to better armed and better informed neighbors. In the struggle for existence, the nations of exploiters and oppressors therefore defeated those who retained their aboriginal communism and their aboriginal democracy.

The capitalistic mode of production has so infinitely perfected the productivity of labor, that this cause for class differences no longer exists. The latter are no longer maintained as a social necessity, but merely as a result of a traditional alignment of forces, with the result that they will cease when this alignment is no longer effective.

The capitalistic mode of production itself, owing to the great surpluses created by it, has enabled the various nations to resort to a universal military service, thus eliminating the aristocracy of warriors. But capitalism is itself bringing all the nations of the world market into such close and permanent relations with each other that world peace becomes more and more an urgent necessity, war of any kind a piece of ruthless folly. If the capitalistic mode of production and the economic hostility between the various nations can be overcome, the state of eternal peace now desired by the great masses of humanity will become a reality. The universal peace realized by imperial despotism for the nations around the Mediterranean in the Second Century of the Christian era—the only advantage which that despotism conferred on these nations—will be realized in the Twentieth Century for the nations of the world by Socialism.

The entire basis of the opposition between the classes of warriors and non-warriors will then disappear.

But the bases of the contrast between educated and uneducated will also disappear. Only, now, the capitalistic mode of production has immensely cheapened the tools of knowledge by cheap printing, making them accessible to the masses. Simultaneously it produces an increasing demand for intellectuals, which it trains in its schools in great numbers, pushing them back into the proletariat, however, when they become more numerous. Capitalism has thus created the technical possibility for an immense shortening of the working day, and a number of classes of workers have already gained certain advantages in this direction, with more time for educational activities.

With the victory of the proletariat these germs will at once be fully developed, making a splendid reality of the possibilities of a general education of the masses that are afforded by the capitalistic mode of production.

The period of the rise of Christianity is a period of the saddest intellectual decline, of the flourishing of an absurd ignorance, of the most stupid superstition; the period of the rise of Socialism is a period of the most striking progress in the natural sciences and a speedy acquisition of knowledge by the classes under the influence of the Social-Democracy.

The class opposition arising from military training has already lost its basis; the class contrast arising from private property in the means of production will also lose its basis as soon as the political rule of the proletariat produces its effects, and the consequences of this rule will soon become evident in a decrease in the distinction between educated and uneducated, which may disappear within a single generation.

The last causes for class distinctions and class oppositions will then have ceased.

Socialism must therefore not only attain power by entirely different means than did Christianity, but it must produce entirely different effects. It must forever eliminate all class rule.

1. Karl Marx, Class Struggles in France, 1848-1850, with an Introduction by Frederick Engels, translated by Henry Kuhn, New York: 1924, pp. 29, 30.

2. Vol. xiii, No. 1, p. 4ff., September, 1894 (Zur Geschichte des Urchristentums)

3. Vernunft wird Unsinn, Wohltat Plage; Weh dir, dass du ein Enkel bist!—Goethe’s Faust.

Foundations of Christianity; a Study in Christian Origins by Karl Kautsky. International Publishers, New York. 1925.

Contents: Introduction, The Personality of Jesus, The Pagan Sources, The Christian Sources, The Struggle for the Image of Jesus, Roman Society in the Slave-holding Period, The Slave-Holding System, a. Property in Land; b. Domestic Slavery; c. Slavery in the Production of Commodities; d. The Technical Inferiority of the Slave-Holding System; e. The Economic Decline, The Life of the State, a. The State and Trade; b. Patricians and Plebeians; c. The Roman State; d. Usury; e. Absolutism, Currents of Thought in the Roman Imperial Period, a. Weakening of Social Ties; b. Credulity; c. The Resort to Lying; d. Humanitarianism ; e. Internationalism; f. The Tendency to Religion; g. Monotheism. The Jews, The People of Israel, a. Semitic Tribal Migrations; b. Palestine; c. The Conception of God in Ancient Israel; d. Trade and Philosophy; e. Trade and Nationality; f. Canaan a Thoroughfare of Nations; g. Class Struggles in Israel; h. The Downfall of Israel; i. The First Destruction of Jerusalem, The Jews After the Exile, a. Banishment; b. The Jewish Diaspora; c. The Jewish Propaganda; d. Hatred of the Jews; e. Jerusalem; f. The Sadducees; g. The Pharisees; h. The Zealots; i. The Essenes, The Beginnings of Christianity, The Primitive Christian Congregation a. The Proletarian Character of the Congregation; b. Class Hatred; c. Communism; d. The Objections to Communism; e. Contempt for Labor; f. The Destruction of the Family, The Christian Idea of the Messiah, a. The Coming of the Kingdom of God; b. The Ancestry of Jesus; c. Jesus as a Rebel; d. The Resurrection of the Crucified; e. The International Redeemer, Jewish Christians and Pagan Christians a. The Agitation among the Pagans; b. The Opposition between Jews and Christians, The Story of Christ’s Passion, The Evolution of the Organization of the Congregation a. Proletarians and Slaves; b. The Decline of Communism; c. Apostles, Prophets and Teachers; d. The Bishop; e. The Monastery. Christianity and Socialism, Index. 480 pages.

PDF of full book: https://hdl.handle.net/2027/uiuo.ark:/13960/t8vc0dv54