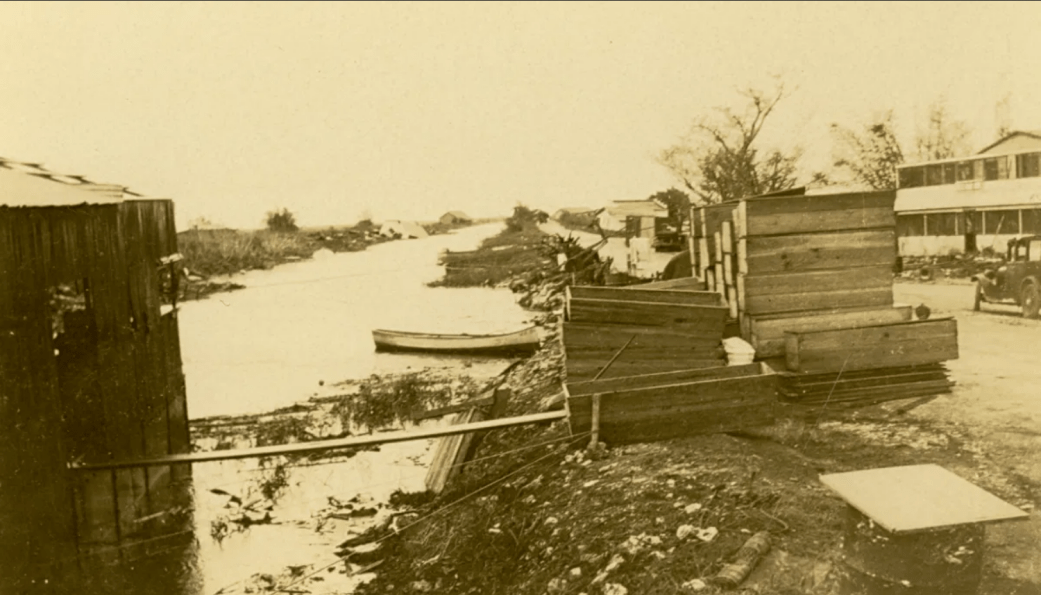

The Okeechobee hurricane that hit Florida in September, 1928 was one of the deadliest in U.S. history, killing over 2,500 people, many of them Black farm workers. Many of those who died were gathered and buried in mass graves by Black victims of the storm conscripted into labor by the Red Cross and state militia as Cyril Briggs tells.

‘Storm and Red Cross Terror’ by Cyril V. Briggs from the Daily Worker. Vol. 5 No. 331. January 24, 1929.

White “Samaritans” Use Murder and Starvation to Keep Negro Workers Under Yoke

FOR thousands of Negro workers in the Florida area visited by the recent West Indian hurricane, the two nights of storm terror were followed by a Red Cross terror far worse than anything in their experience during those two awful nights. To the horrors of a storm which snuffed out the lives of hundreds of relatives and friends and contemptuously crumpled up the miserable, match-box shacks in which most of the Southern Negro workers are forced to live, by low pay and intensive exploitation, there was added a brutal terrorism against Negro workers and a cynical discrimination in the distribution of food and other relief by the Red Cross and its local agents.

Negro workers were taken from the sides of their sick wives, terror stricken children and unburied dead and conscripted for forced labor, without pay, at the most arduous and unpleasant tasks. Negro crews were sent out to “fish” for dead bodies; others were forced to work in the kitchens in the white tent colonies. The state militia was used to round up conscript labor from among the Negro refugees, and functioned with the utmost brutality. Many Negro heads of families in a desperate hunt for work of some kind to help their starving families ran afoul of the state militia.

Edward Tolliver, one of these, was on his way to Belle Glade to hunt for work in order to relieve the tragic plight of his family, when he was conscripted and forced to work picking up dead bodies for two weeks without pay. Coot Simpson, a 35-year-old Negro worker, was shot down by a white guardsman at 8th and Division Sts., West Palm Beach, because he did not obey the order to “climb on that truck, nigger!” but insisted on explaining to the guardsman that he was working for a white man across the street and would have to “get the permission of my boss.” Simpson started to walk across the street to his place of employment and was shot down by the guardsman, the bullet piercing his back and causing instant death. The guardsman was subsequently exonerated by a jury of white men. Simpson leaves a wife, too sick to work, and two little children, a girl of nine and a boy of ten. Conscription of labor Was confined to Negro workers.

All the time the Red Cross did little or nothing for the Negro sufferers. The families of the conscripted men were left to starve or beg a few crumbs at the back door of the more fortunate white refugees. Scores of Negro refugees were driven away from Red Cross stations. Many more were deterred from making application for aid after learning how others had been driven away.

Even Levi Brown, the hero of the storm, was ill-treated at a Red Cross station. This Negro worker, who saved the lives of scores of people, white and black, while the storm was at its worst, dared to go into a Red Cross mess hall in Belle Glade one day following his return from a hazardous “fishing” expedition. One of the workers in the mess hall, who knew of Brown’s heroic life saving exploits, gave him some food, including a piece of ham. The Red Cross director, catching sight of Brown, uttering the vilest oaths, and telling him that “ham was not for n***s,” grabbed an 18-inch axe and made a ferocious assault on him. This Red Cross director was in charge at Belle Glade from September 17th to October 28th. In many cases colored families with children were allowed only two to three dollars worth of groceries a week, while white families without children would be given six and seven dollars worth.

This statement is based not only upon the complaints of the Negro refugees, but upon the findings of a trained investigator. A.L. Isbell, field organizer of the Negro Workers’ Relief Committee, which has national headquarters at 169 West 133 St., New York City, reported to his organization:

“From my observation the Red Cross simply didn’t function in many places when it came to colored people. The food distributed seems to be mostly milk and bread. Colored people who were working for whites or had white ‘patrons’ to intercede for them got a little consideration. Those lacking such ‘patrons’ had to get thru in the best way they could…In all these sections the persons handling relief distribution are the very ones whose attitudes are most marked by prejudice.

“I have met every Red Cross director in Florida and patiently listened to their cant about the broad policies and principles of the Red Cross relative to distribution of relief to all persons alike in this time of disaster. And I have gone from them into hundreds of Negro homes and seen first hand evidence of rank discrimination against Negro workers. I have listened to bitter complaints of discrimination on every hand. I have visited the Red Cross tent colonies for Negro refugees and I have been through their colonies for white refugees. The difference is marked. In the white colonies the tents have floors, and the sanitary arrangements are perfect. In the Negro tent colonies, most of the tents are without floors and ten and twelve persons are often crowded into one small tent.”

That the Red Cross functioned in Florida in its historic role of an instrument of prejudice and oppression against the Negro workers; no one who reads the reports of the Negro Workers’ Relief Committee can doubt. This committee has not only undertaken an important and essential task in attempting to organize the workers, black and white, for solidarity with the Florida Negro storm sufferers to relieve their present needs for food and clothing and home rehabilitation, but has done a splendid service in exposing the Red Cross among the Negro masses. It has clearly shown the Red Cross as having functioned in two recent disasters, the Mississippi flood and the more recent Florida hurricane, to strengthen the present vicious social conditions in the South.

It is the goal of the Negro Workers’ Relief Committee to organize as a permanent Negro relief body which, after having won the confidence of the Negro masses, could mobilize large sections of Negro workers to the support of other workers in strikes and natural catastrophes. The committee is still engaged in Florida relief work and is making an appeal to all organizations of workers, labor unions, fraternities, etc., for funds to carry on its relief work among the Florida Negro storm sufferers. The committee points out that while relief work among the white storm sufferers has reached the secondary stage of home and farm rehabilitation, among the Negro sufferers, the first, stage, that of supplying the bare necessities of life, has not yet been passed.

The Daily Worker began in 1924 and was published in New York City by the Communist Party US and its predecessor organizations. Among the most long-lasting and important left publications in US history, it had a circulation of 35,000 at its peak. The Daily Worker came from The Ohio Socialist, published by the Left Wing-dominated Socialist Party of Ohio in Cleveland from 1917 to November 1919, when it became became The Toiler, paper of the Communist Labor Party. In December 1921 the above-ground Workers Party of America merged the Toiler with the paper Workers Council to found The Worker, which became The Daily Worker beginning January 13, 1924. National and City (New York and environs) editions exist

PDF of full issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/usa/pubs/dailyworker/1929/1929-ny/v05-n331-NY-jan-24-1929-DW-LOC.pdf