A wobbly on the road with he circus tells of the workers, their conditions, and the everyday swindle in this delight piece for ISR.

‘Under the Big Tops’ by A Ballahoo Wobbly from The International Socialist Review. Vol. 17 No. 8. February, 1917.

It was in a southwestern town where one of the biggest circuses in America winters that I first felt the call of the Big Top and got a job with the show, just starting out to make the first towns in the spring. “Happy” Holmes, treasurer of the company, hired me, and I remember that his wife prophesied that ever after would I feel the call of the saw dust whenever I heard a band go up the street.

And there was some truth in what she said. It is funny how a man will return to the kind of work he has pursued, year after year. Doing the same thing, traveling with the same people, acquiring the wanderlust and being in debt to the Big Boss, all have a tendency to tie you to circus life, just as other job-ties drag you back to the shop, the mine or the mill until you get the habit.

I suppose every boy sometime feels that life could hold no greater joy than to call him to earn his living under a circus tent. There is a sort of a romantic glamour about the clown, the elephants and the animal cages, the calliope that some of us never quite outgrow. This glamour is what gathers in the boys who have left home and gone out “on their own.” Working in a circus seems to them to be an ideal way to earn a living. But the wise youngsters soon find some more attractive job on one of our stops and drift away.

Most workingmen are on the tramp when they join a show. A tramp makes the most desirable worker for the circus boss. He will usually suffer more hardships, complain less and stick till his wanderlust takes him to another show. And when he quits, it is possible for the boss to keep his two weeks’ pay, which is always held back in the show business.

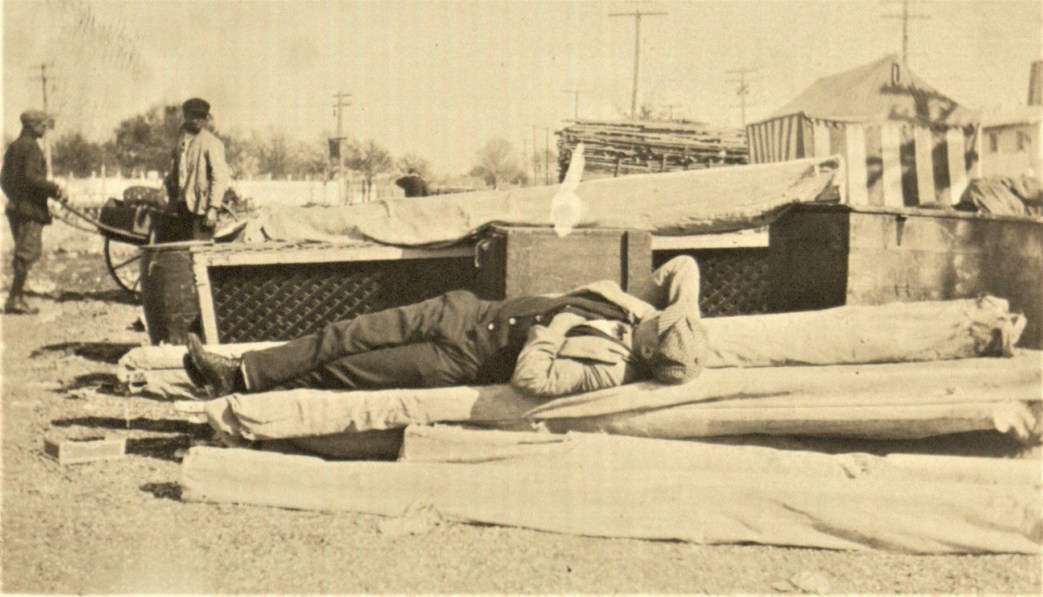

The boys looking for adventure, travel, etc., who get work with a circus, wake up soon. They find they have to work a long time before breakfast in order to unload the cars, start putting up the canvas and think about the street parade, and that supper is served (?) at 4:00 p. m. while the work of pulling up stakes and loading on the cars may go on nearly all night.

The laboring men with the circus are nearly always the most hopeless, dejected lot under the sun. I never met but three I.W.W. men on a circus — and they didn’t stay long.

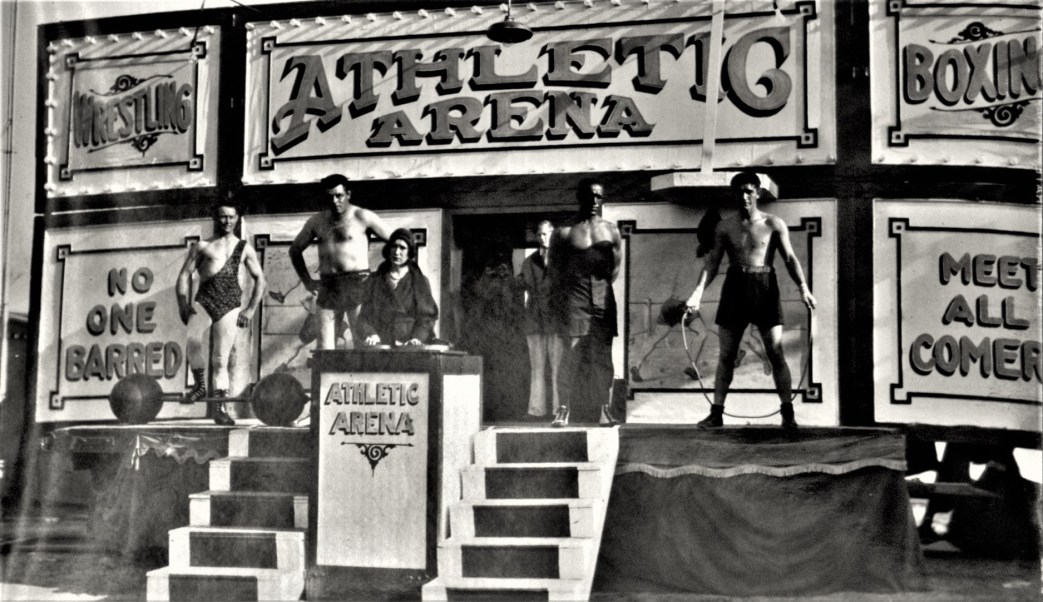

The men who unload the train are called razorbacks, roughnecks and roustabouts. Men who hold the pole of the wagon when wagons are being taken up the runs are called pollers. They have the most dangerous job on the whole show. Leaps, aerial acts and race, or fancy riding, are dangerous, but nothing compared to the unrecognized work of these men, and those who put up and tear down the big tops.

Of course these men are loaded into bunks like cattle to get a little rest before the next town and unless they wear whatever extra clothes they possess, or sleep with their heads on any suit case they may be fortunate enough to own, they will be robbed in their sleep. The bunks are creeping with vermin and it is almost necessary for a new man to drink himself into insensibility to be able to get any real rest.

We performers, etc., etc., have better sleeping conditions, but our cars are a long way from being sanitary.

The men who put up and take down the tops usually get about $5.00 a week. But, of course, this includes meals and bunk. Almost every circus carries a “privilege car” owned by the company, and to enter it is usually a privilege for which you have to pay dearly. There is a lunch counter, a bar, and two or three gambling games going all the time. Here is where the company has a chance to clean up on any left-over a man may have from his wages. Here everybody with money in his pocket is welcome as the flowers in May.

The company holds back two weeks’ pay and it is a company law that anybody quitting must give two weeks’ notice. This is stipulated in all circus contracts. In this way every circus gets a lot of work done for nothing. When a workingman runs up against a good job in some new town he cannot afford to work on two weeks longer with the circus and pay his fare back, even if the job is still open.

Food that goes to the performers, ticket sellers, ballahoo boys, musicians, side show people, bosses and candy-butchers is a little better than that served to the hardest workers. The grafters, fixers, proprietors, managers, etc., eat at tables removed from the common herd, who merely put up the tents and give the performances and these folks get about as good as is going.

You might think you would like to see dinner or supper in process of preparation in the big cook tent, but you would not care to witness a sacred rite profaned more than once — for the sake of your appetite and your stomach.

During long runs the roustabouts (who do the heaviest work) often have to go twenty-four hours without eating, unless they have the wherewithal that gives them access to the Privilege Car and the lunch table. It is common to have breakfast at 11 .00 a.m. after a supper at 4:00 p.m. the previous day.

Of course there are always a few sluggers or stool pigeons for the show. Often when a workingman gives his two weeks’ notice, these sluggers will run him away. Sometimes when there are extra men looking for a job, these sluggers will tell the regular men not “to ride the train,” and prevent them from riding to the next show town, thus saving their back pay for the company.

I have seen the train stopped and a bunch of workingmen forced off or thrown off only half dressed when the show was more than “full-handed.” But not many circuses still practice this thieving trick against the workers. The performers put up a big kick when they see a worker “redlighted” nowadays.

A show now often offers a bonus of $5.00 a month to the men who will stick out the season, and sometimes they pay the bonus and sometimes they don’t. They often put up a claim of losing money and refuse to pay anybody anything. And then what are you going to do about it?

Some men go to a Justice of the Peace, but you can’t help thinking that these men have usually been “fixed” and fixed right — for the company. You will find that the old fellow has gone to bed — at seven o’clock! and refuses to be disturbed. There are always reasons why nothing can be done while the circus is in town, and what can a workingman do when the circus leaves town?

A circus keeps a lot of workingmen and performers around winter quarters, the workers to build new scenery, new trick trapeze or other things and to repair the show, and the performers to learn new high dives, aerial acts, dare-devil stunts, to train new animals, etc., etc. The workers get 50 cents a week on Saturday nights for tobacco, and board and bed — such as they are. Talk about pauper labor! Surely the Big Top in America has the world skinned!

And speaking of winter quarters, I recall a young lad who was ambitious to do daredevil stuff. There are always youth like this who are drawn to a circus like flies around honey pots. One company boarded this youth half a winter and taught him to become, according to the bill posters:

“Jack Dare-All, The Human Arrow, Beyond the Limit!” by having him ride down a steep incline on a bicycle, leap from his wheel fifty feet in the air and take a somersault dive into a tank of water — all for a four-year contract at $15.00 a week, while the circus was on the road!

The “property boys,” or men whom you have seen around the ring arranging rigging for performers, etc., etc., get $3.50 a week. It is customary for the performers to “tip” these boys or men and the company takes this into account when paying them. They get less than the “roustabouts.”

Circuses have a number of ways of “grafting” on the performers, but I will not take up these. I have only tried to give you an idea of what life for the workingman means in the circus.

This life fairly screams for an I.W.W. organizer. If we had a bunch of industrial unionists on the job for one season we would have a revolution in the circus business. Everything here depends upon the roustabouts — almost, just as it does in every branch of industry. The workers could control their jobs here if they were only organized — right.

An interesting thing happened when we showed at Hibbing, Minn., last summer, when the miners were out on strike. The graft on the “sucker” public had been going good in a lot of towns, we heard. The side-shows had been full of games of “chance” (?) wherever it was “safe” for the circus graft crews, where there was no such thing as a percentage in favor of “The House.” The men in charge of the games determined just when a player was to win or lose. And the fellows who sold tickets returned small bills for large ones in making change — to their own profit.

But in Hibbing, I am assured, the sheriff told our graft crews to go as far as they liked; that anything was O.K. so long as they helped clean the pockets of the strikers. So the lid flew off on the gambling games and short-changing was worked as it never had been worked before.

PDF of full issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/usa/pubs/isr/v17n08-feb-1917-ISR-riaz-ocr.pdf