Austin Lewis was the leading Marxist theorizing industrial unionism in the United States before World War One. Among his most important works, meant to become a book, were a series of articles on on the politics, economy, and psychology of ‘solidarity’ for the New Review. Here he looks at the Wheatland hop workers strike for the ‘basis of solidarity.’

‘The Basis of Solidarity’ by Austin Lewis from New Review. Vol. 3 No. 12. August 15, 1915.

THOSE trades which make alliances for the purpose of united action against an employer are by the very nature of the case shut off from any comprehension of solidarity. The apparently effective stand made by such trades is due to temporary advantage of situation and the victory thus gained is precarious. Such victories, and they are admittedly of diminishing frequency, cause a loss rather than a gain in the direction of solidarity. For the victorious portion of the trades, seeing that their fellow workers have not contributed to their victory, are rendered the more confident of their ability to maintain their position without the assistance of the others.

This rule applies to all those trades which by virtue of the possession of specialized skill and consequently of a greater or less power of gaining a monopoly in the market as regards that skill are able to “control” the job and make a “closed shop” for their particular labor-power commodity.

It also applies to such other trades as, by virtue of the local conditions, find themselves temporarily in “control” of the situation, and, able to keep the distribution of jobs in their own hands. This has happened quite frequently in the far West for the former comparative inaccessibility of that region gave the craftsman a peculiar though, of course, transitory advantage.

To such as these the term “solidarity” naturally conveys no meaning, or one that is essentially idealistic. The ordinary unionist under such conditions, never feeling the need of solidarity, as a matter of fact, does not know the word, and the radical or socialist unionist sees in it only that “ideological” quality already spoken of.

The essence of solidarity is “coherence of interest” (Standard Dictionary). At this point we may apply the Marxian doctrine with advantage. By “interest” we mean economic interest. Where the interests are identical or coherent solidarity follows automatically. On the contrary where the interests are not such as can be called coherent there is no solidarity.

We can predicate almost with certainty, in the absence of limited and local circumstances, how various sections of the community will vote with respect to taxation and other matters directly affecting classes. We know that a threatened raise of taxation which would impose a burden on the small middle class will be met by the united resistance of that class. The solidarity of the class arises at once and automatically. It is not a theory, neither is it an aspiration. It is a fact. Indeed it is the fact upon which the threatened class relies for its protection or salvation.

Solidarity, then, rests upon no sentimental or “ideological” basis but, like every other concept of any value, upon a definite substratum of fact. Where this does not exist the very essential element of solidarity is lacking and the term becomes a mere idle expression of no significance, other than mystical.

The socialists, indeed, base their “solidarity” upon the irreconcilability of the interests of the workers with those of the capitalists and declare that the political solidarity of labor must follow automatically and necessarily from that fact.

But there are actually cases where the interests of certain portions of the laboring class are apparently with certain groups of employers rather than with the laboring masses, as Kautsky and others have admitted in their classification of the revolutionary elements. What becomes of the solidarity of labor under such circumstances?

A”solidarity” results, but it is between the groups whose economic interests are more nearly identical between the particular capitalist group and the labor group whose interests for the present seem to correspond. Hence we have the every day phenomenon of the political support given by the craft labor element to the smaller middle class. The organized craftsman is still, particularly in the West, a potential member of the smaller middle class and all his aspirations are bound up with that class rather than with the unorganized and relatively unskilled portion to which the term proletariat may be more particularly applied.

To make an arbitrary classification of society upon the basis that it consist of the greater capitalists, the smaller middle class and the working class, is not satisfactory, for, were it true, it could have no very clear meaning, unless we can define what is meant by “working class.” Indeed it is just at this point that the criticism of the ordinary man in the street is directed. He always meets this classification with the question “What do you mean by the ‘working class?’ ” If he is a professional man he generally adds rather scornfully “I am a working man myself.”

Unless we can determine what we mean by the working class we are no nearer a solution of the difficulty. The only test is the Marxian economic test. We must analyze the various economic ingredients which go to the making of the “working class.” The result of this analysis does not reveal that homogeneity, that compelling “coherence” which must be regarded as the prime essential quality, without which no solidarity is possible.

At this point the official socialist has refused to proceed further. Only in the recent discussion by Kautsky, Pannekoek and a few others do we find any reminder that the nucleus of skilled workers comprising the unions that has taken to itself the name “working class” does not constitute the whole of that body.

Later examination moreover leads to the conclusion that such a nucleus does not in reality comprise even the really effective fighting portion.

This is by the way, however; the point to which we wish at present to call attention is that such differences are in themselves proof of the absence of solidarity. For solidarity cannot exist between such divergent elements. In reality it does not exist, as experience in the labor movement and its manifestations amply testify.

A rather interesting example of this appeared during the Los Angeles strike of 1910. A parade was to be held and it was imperative that as representative a showing as possible should be made of the laboring class in that city. The strike was conducted by the metal trades and was supported generally by organized labor throughout the state. Los Angeles rests fundamentally upon a basis of unskilled labor, foreign unskilled labor, notably Mexicans, Russians and Italians. This foreign unskilled labor had of course no place in the trades organization of Los Angeles. It was not represented in the labor council and, in spite of the fact that numbers of this unskilled labor class were going into the shops and keeping them running, no effort had really been made to awaken their interest and to placate them. The labor unrest had however affected the Los Angeles working population to its depths. After some agitation therefore numbers of the foreign unskilled expressed their willingness to parade with the organized trades. They did so to the number of about two thousand, almost all Mexicans. It was the first time in the history of the Coast that this class of labor had paraded with the organized trades; and it was painfully, almost ludicrously, out of place.

The unions marched in the van with their crafts organization banners and the national flag at the head of each division. But what emblem could the unskilled workers carry? The fact, however, as usual produced its own expression and the Mexican workers paraded under the Marxian adjuration “Workers of the World Unite.” The craft organizations expressed themselves in trade mottoes and national flags; the unskilled with their mass organization could find no other expression than a statement of that solidarity which their condition demanded.

In short solidarity cannot be founded on a philosophical theory nor on political activity and propaganda. To take out a red card does not mean that one is a proletarian or that the same economic influences are not at work with the holder of the red card as effect others of the same economic proposition as himself.

Solidarity is a fact and rests on a fact. That fact produces an unconscious psychological reaction. Stress must be laid on the word unconscious. The reaction is so direct as to be practically automatic. And to say this is to say no more than the Marxian student admits to be a theoretical commonplace which however he frequently ignores in practice.

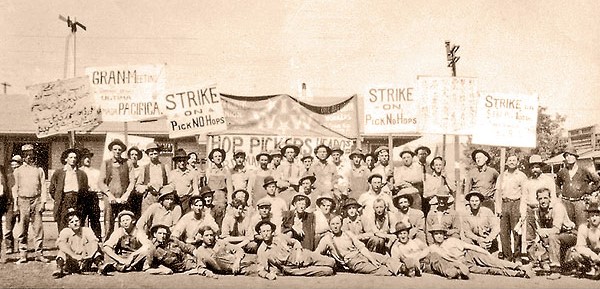

An instance of the working of this unconscious solidarity resting essentially and indeed solely upon the economic fact may be seen in the later developments of the hoppickers’ strike at Wheatland, California.

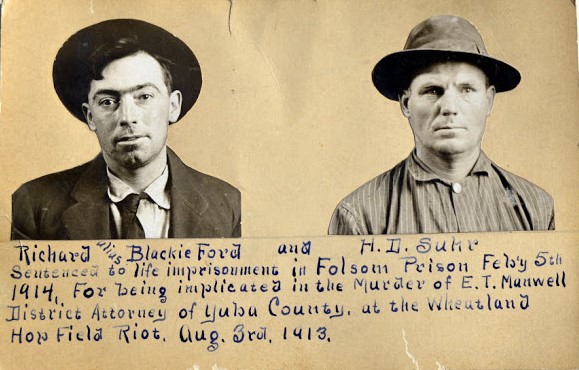

This strike was in itself a pure example of mass action for it was without prior organization and flared up spontaneously under the pressure of certain conditions which were later adjudged by public opinion to be also inhuman. As a result of this spontaneous strike two men were found guilty of murder in the second degree. The Industrial Workers of the World had taken up the matter of the defense of the men, and subsequent to their conviction placed the demands of the hoppickers on the Durst ranch where the trouble had occured as the minimum demands of hoppicking in the State of California. These demands were promptly conceded by the employers, and the State Commission on Housing and Immigration suggested and enforced sanitary measures which it is safe to say had been unheard of in the State prior to the uprising on the Durst ranch.

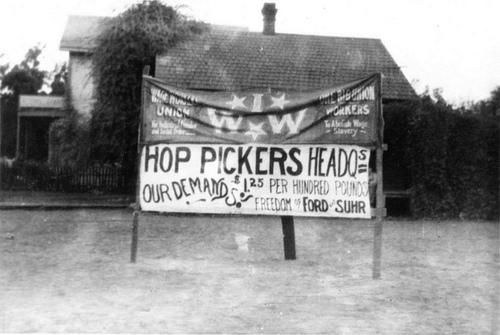

But this victory was not enough. Ford and Suhr were in jail. These were the two men who had been convicted of the murder of the district attorney already mentioned. They were considered by the mass of the laboring people everywhere to have been unfairly convicted and much indignation existed throughout the State on that account. Accordingly the committee of migratory workers who had taken charge of the matter issued broadcast statements that there would be no hops picked unless the two men who had been convicted and whose cases were now pending in the appeal court were released.

To the ordinary unionist and the business man this demand seemed to be the acme of absurdity as well as of stupidity, for did it not show an entire ignorance of existing social and political conditions? The hopgrowers, that it to say the employers who were organized in the Hopgrowers Association, consulted with the Industrial Workers, an organization which hitherto they had utterly despised and scorned in an endeavor to reach an agreement. They offered to concede everything which the committee demanded. “But how about the release of Ford and Suhr?” they were asked. The hopgrowers answered indignantly with another question, “How can we release Ford and Suhr?” To which the astute committee replied, “By the use of your economic power just as we are going to use ours to prevent your hops being picked.”

Such an undertaking would apparently be doomed to failure from the start. There was no effective organization such as we generally understand. There was no money to do more than advertise more or less widely the fact that a boycott of the hopfields was contemplated. The hoppickers, as we have already pointed out, consisted of the under stratum of workers and were racially and otherwise without any homogeneity. Yet the Japanese and the Indians on the reservations who were accustomed to take part in the hoppicking equally declared their intention of remaining away from the fields and there was a general movement among the Latin people, who furnish the largest quota of pickers, not to undertake the work although times were hard and there was a lack of employment in the cities. To add to the wonder of it all the Building Trades Council of San Francisco as well as the Labor Council each endorsed the boycott to the extent of advising their members to keep away from the hopfields. In the latter case the motion was carried in spite of the objection of two of the most prominent and strongest leaders in the council and was indicative of a sympathy on the part of the masses of union men with the migratory worker. As regards the two labor bodies the action was purely sympathetic and rested in the main on human impulses for their members were not interested in the hoppicking industry and very few of them had ever or probably ever would take part in it. Other labor councils followed this lead.

Where can we look for the main impetus to this solidarity of action? As regards the first spontaneous movement, the answer is ready, for the conditions were such as in themselves to produce the revolt which spontaneously occurred. But as regards the boycott the conditions were so different as to merit notice. All the old grievances had been practically abolished. It was generally conceded that the conditions were beyond expectation better than they had ever been, hoppicking appeared more inviting as an occupation both from a sanitary standpoint and in respect of actual economic returns than ever before, and yet we had the united action of large bodies of men differing widely in speech and modes of life.

This action moreover was directed to a distinctly nonpersonal end, the release of two prisoners, whom the vast majority had never seen and had only heard of as champions of the common cause. It is very doubtful if we have ever had a more complete example of the operation of the solidarity notion than in this instance. The contrast between this spontaneity of expression and the labored alliances of the organized trades is too apparent to require pointing out.

This solidarity involved more than a mere demand for better conditions of employment. It refused to recognize the limitations of legality as expressed in terms of the state and the dominant class in whose interests the state was managed and the laws enforced. It declared itself as an effort to impose the will of a distinct body of men, the migratory workers, on the community and so far was a demand for status. In other words it was a solidarity founded upon an economic basis and embracing all the members of a certain economic category.

The New Review: A Critical Survey of International Socialism was a New York-based, explicitly Marxist, sometimes weekly/sometimes monthly theoretical journal begun in 1913 and was an important vehicle for left discussion in the period before World War One. Bases in New York it declared in its aim the first issue: “The intellectual achievements of Marx and his successors have become the guiding star of the awakened, self-conscious proletariat on the toilsome road that leads to its emancipation. And it will be one of the principal tasks of The NEW REVIEW to make known these achievements,to the Socialists of America, so that we may attain to that fundamental unity of thought without which unity of action is impossible.” In the world of the East Coast Socialist Party, it included Max Eastman, Floyd Dell, Herman Simpson, Louis Boudin, William English Walling, Moses Oppenheimer, Robert Rives La Monte, Walter Lippmann, William Bohn, Frank Bohn, John Spargo, Austin Lewis, WEB DuBois, Arturo Giovannitti, Harry W. Laidler, Austin Lewis, and Isaac Hourwich as editors. Louis Fraina played an increasing role from 1914 and lead the journal in a leftward direction as New Review addressed many of the leading international questions facing Marxists. International writers in New Review included Rosa Luxemburg, James Connolly, Karl Kautsky, Anton Pannekoek, Lajpat Rai, Alexandra Kollontai, Tom Quelch, S.J. Rutgers, Edward Bernstein, and H.M. Hyndman, The journal folded in June, 1916 for financial reasons. Its issues are a formidable and invaluable archive of Marxist and Socialist discussion of the time.

PDF of full issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/usa/pubs/newreview/1915/v3n12-aug-15-1915.pdf