‘The Green Corn Rebellion’ by Leighton Rigby from New Militant. Vol. 2 No. 7. February 15, 1936.

If American workers are generally unaware that in 1917 three-quarters of a million men were preparing to march on Washington and wrest the reins from the “Big Stick” and his war birds, it is only further proof that the domain of patriotism is a disenlightened realm indeed. Press files yield little concerning the Corn Rebellion; inspired histories make no mention of it; and even the venerable Dr. Beard passes it without a word. But the memory must not be lost in the darkness of the late war. There are two reasons for the failure of the movement: timid and irresponsible leadership, and unsuitable circumstances for success.

The first cause, if recognized as a fact, needs no elaboration. The second is also understandable when we consider that capitalism was firmly in the saddle, by virtue of a wartime “boom,” and was further fortifying its position by deep jabs with the needle of patriotism. Even though it failed to materialize, however, the proposed march on Washington gives us reason to know that the Draft Act of 1917 was not “accepted by the people of every section.”

Opposition to War

Before the press, movies, song writers and spell-binders could build up the maximum of war hysteria, there was much trouble throughout the land. I.W.W. organizers, unsound, perhaps, but ambitious, were busy on the West Coast and in the East. Thirteen hundred objectors were deported from Bisbee, Arizona, and herded into a stockade at Hermanas, New Mexico.

Forest fires and bombings were blamed on those who opposed the war, whether the blame was well placed or not. Lack of organization alone prevented unrest and doubts from assuming real significance.

After the exposed portions of the country became ill with war hysteria, there still remained certain parts of the U.S. where the disease was unknown. One of these included several counties in Oklahoma and parts of neighboring states. That section provided the locale for the Corn Rebellion.

In accounts I have read of the reception of the Draft Act in Oklahoma, too much emphasis has been put upon the backwardness of the people involved. This condition has been offered as the main excuse for the mobilization against war service.

Without a doubt, the fact that newspapers were not generally read and movies were seldom seen did tend to retard the growth of the war spirit among the tenant farmers of Oklahoma. But how backward were they, really?

The Burden of Oppression

It must be remembered that these people were oppressed by urban money lenders who often demanded —and got, if crops were sufficiently good—four or five times the conventional rate of interest. Also, there was little good land at the disposal of poor tenant farmers. Good crops were rare on the shrubby soil that was left after investors had taken the choice land. And there was an important result of this oppression: the poor farmers became daily more class conscious and were convinced that a capitalist war concerned their final interests not at all.

This class consciousness naturally turned the people toward the doctrine of Karl Marx. In several of the counties affected, the Socialist vote in 1914 was over one-third of the total cast. I do not mean to infer that this, in itself, meant a definite revolutionary trend. I merely state that if being “backward” means lacking the quality of cheering the spirit of progress while being oppressed by that same progress, these people were backward. I prefer, however, to think those people backward who are oppressed and see no glimmer of hope for relief.

The Working Class Union

Toward the middle of 1914, the Working Class Union was organized In Arkansas. The original purpose of this organization is not known to me, but as the entrance of the U.S. into the World War came nearer, the W.C.U. began to advocate overthrow of the capitalist government in Washington. Leadership was poor from the start, but by 1917 some 36,000 farmers in Oklahoma and surrounding states alone were able to embrace the broad pattern of the Working Class Union.

The strategy to be used in connection with the march on Washington was briefly this: on a given day, the local chapters would gather and march to a specified point where they would be joined by other groups of the district. This army would set out for Washington.

Along the way, the size of the army would be enlarged manyfold by the addition of new recruits and previously readied groups, e.g., among the I.W.W. Barbecued cattle and roasted green corn would constitute the food supply.

It is true—the leaders, the fiery orators were idealists, unsound in theory. And they were also timid. Their smooth flow of words had won many to the banner of the W.C.U.; but after this was done, they either demonstrated their utter incompetence to lead or ran away.

The Battle and Its Outcome

After several false starts, in August of 1917 the W.C.U. in the Oklahoma district began to mobilize. No great numbers came to one spot, but several small groups were formed. At the behest of civil authorities several posses of less “backward” urban citizens were organized to bring the “draft dodgers” to the bar of “justice.” There were a few skirmishes, but without good leadership, the case of the tenant farmers was a hopeless one. Only at Holdenville, where two members of a posse and one W.C.U. member were killed, were there serious casualties.

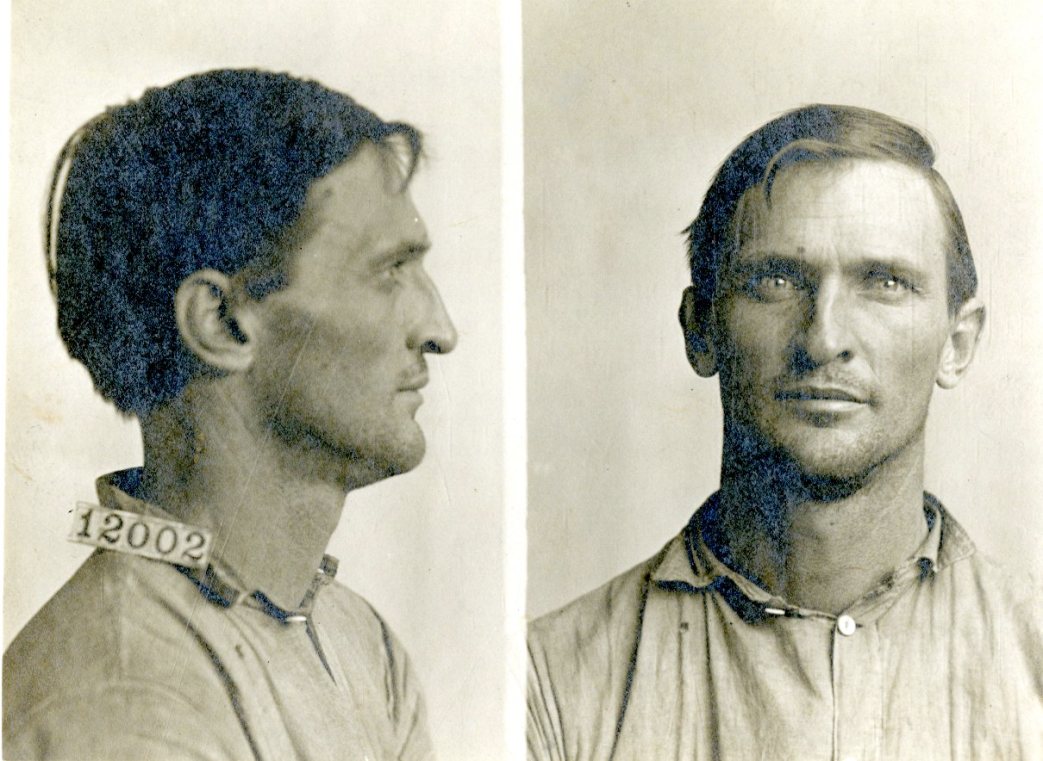

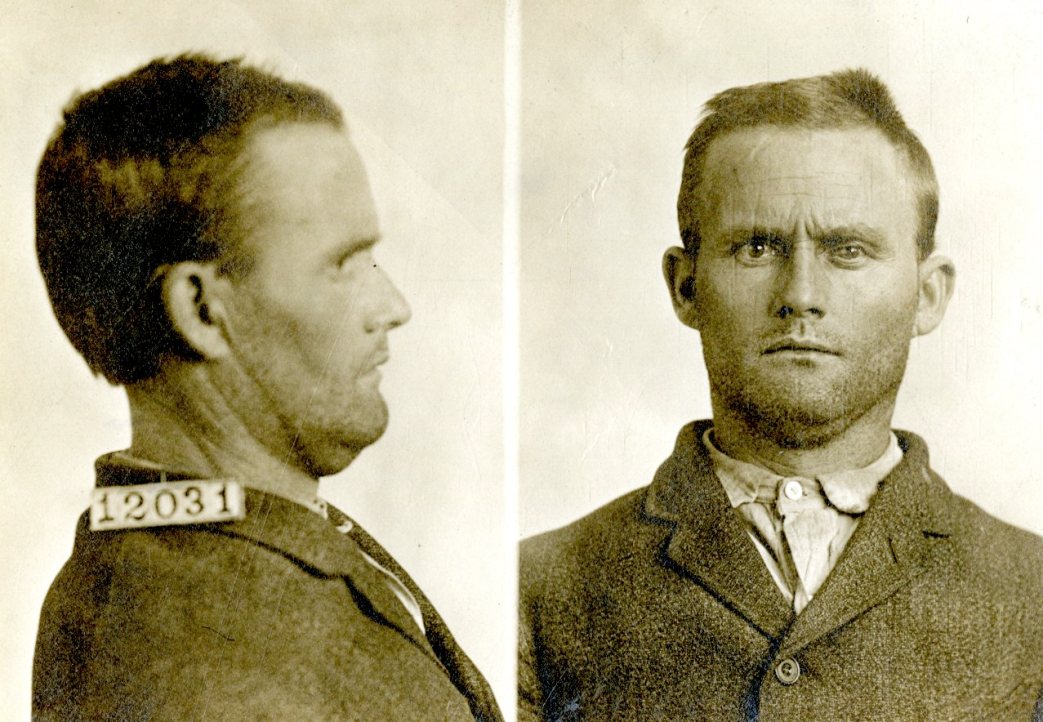

Several hundred members of the W.C.U. were made prisoners, and nearly a hundred were later sentenced to prison, federal or state. Those who were set free received advice in the matter of patriotism from kindly and “enlightened” judges.

The Corn Rebellion was put down. It was bound for failure from the first. But it stands as proof that class conscious American workers will not willingly fight for the interests that oppose them and beat them down.

The New Militant was the weekly paper of the Workers Party of the United States and replaced The Militant in 1934, The Militant was a weekly newspaper begun by supporters of the International Left Opposition recently expelled from the Communist Party in 1928 and published in New York City. Led by James P Cannon, Max Shacthman, Martin Abern, and others, the new organization called itself the Communist League of America (Opposition) and saw itself as an outside faction of both the Communist Party and the Comintern. After 1933, the group dropped ‘Opposition’ and advocated a new party and International. When the CLA fused with AJ Muste’s American Workers Party in late 1934, the paper became the New Militant as the organ of the newly formed Workers Party of the United States.

PDF of full issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/etol/newspape/themilitant/1936/feb-15-1936.pdf