‘The Story of Labor Day’ by Thurber Lewis from The Daily Worker (Saturday Magazine). Vol. 3 No. 200. September 4, 1926.

THERE is more than one way in which the capitalists have time and again attempted to thwart the ambitions of labor. Wherever it seemed impossible or undesirable to attack labor headlong and directly, the master class would proceed in a roundabout way, but always pursuing the same objective, which is to prevent the crystallization of class consciousness and class organization among the workers.

Labor Day was conceived as labor’s day. It promised to become, like May Day, a symbol of working class solidarity against the capitalist class. But it didn’t. The capitalists together with their henchmen in the labor movement have accepted Labor Day as their own day, and in doing so have killed the soul of what should have become a day of real working class struggle.

Labor Day was made into a perfunctory, official holiday. It has become a legal holiday by act of congress and the legislatures of thirty-two states. The banks observe it. Everything is closed down. Factories stop. The mines are shut. None but the wheels of necessary transportation move. But not because the workers will it. Not because of a show of main strength by the toilers in whose name this hollow tribute is observed. No! The factories close, the working class rests on that day because the masters themselves recognize the day and rest also. However, as the American labor movement becomes more militant and conscious, Labor Day also will become transformed into a day of struggle against capitalism.

How did Labor Day come about?

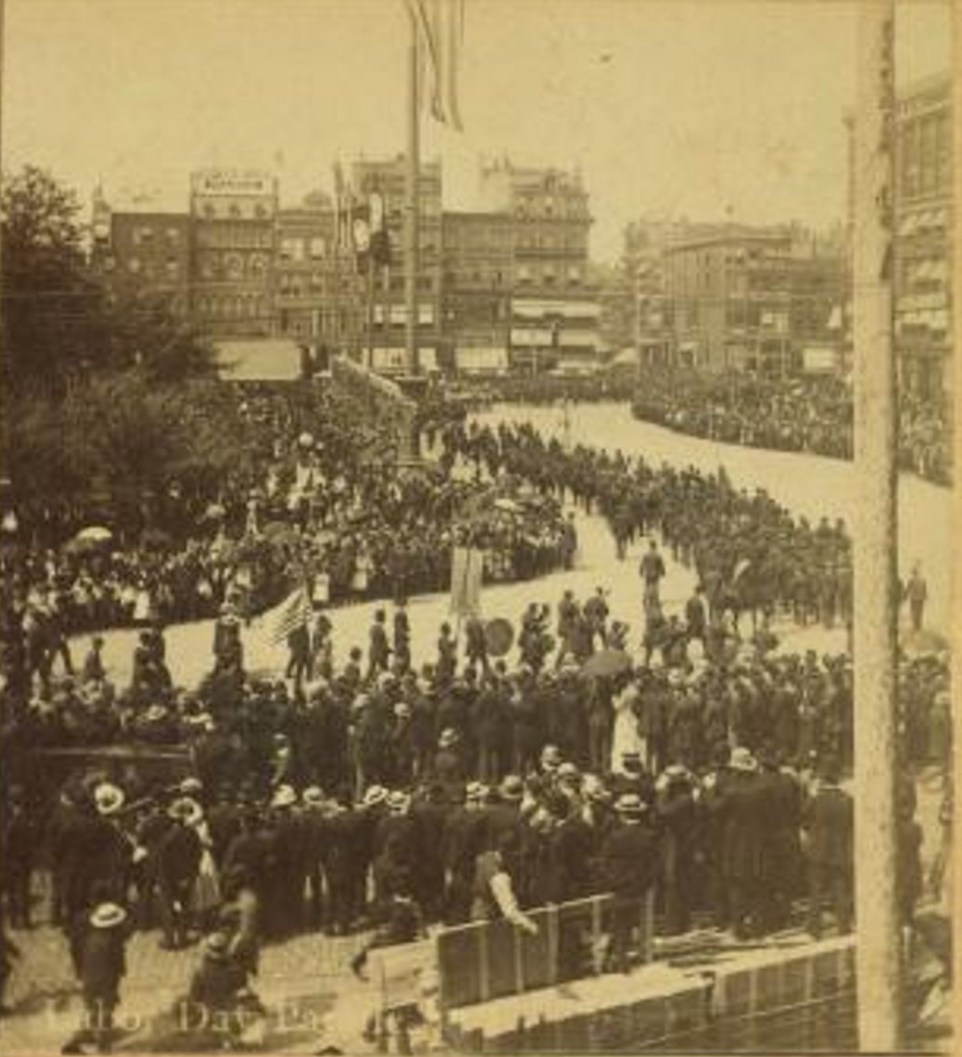

It was first suggested in the New York Central Labor Union in May, 1852. On the first Monday of the following September, a parade was arranged that terminated in a picnic at which speeches were made by labor orators. Two years later, in 1884, the American Federation of Labor, sitting in convention declared the first Monday of every September, Labor Day. In the resolution all wage earners, regardless of sex, race or nationality, were urged to observe the day until it should become as common as July 4th. Various states were persuaded to make the day a legal holiday.

So far so good. Labor Day celebrations were held in all the large cities. Some of them were impressive. The movement was young and virile. In the early eighties it was picking up steam for the battles to be fought at the end of that decade. In 1886, a huge parade was held on Labor Day in New York, which was made part of the campaign to elect Henry George mayor of New York City. Sam Gompers was there and aided in the campaign. Injunctions were being used on a wide scale and with impunity in a number of strikes that year in New York. “Down with Injunctions” was one of the slogans of the day. Gompers spoke from the same platform with Henry George and told the workers to violate the injunctions.

Then came the eight-hour movement. The American Federation of Labor was the initiator and the moving spirit of this memorable campaign. The Knights of Labor, grown to great power by this time, made a fatal error in refusing to participate officially in the movement for the eight hour day. But the A. F. of L. went forward with the preparations for the calling of a nation-wide eight-hour strike on May 1, 1886. May 1 was the logical time, with summer in the offing to fight the battle rather Labor Day with winter around the corner. That is how May Day came to be. And that is how May Day superseded Labor Day—why May Day is part of the flesh and blood of the movement. But Labor Day was continued. Yes. But that is another story.

The strike was called. The response was enthusiastic. Great gains were won for the workers. But on the 3rd of May came the Haymarket—the bloody conspiracy against again a handful of virile, revolutionary leaders of the workers that was in fact aimed at the growing militancy of the workers’ movement in general and the eight-hour campaign in particular. The reaction to this violent reprisal was terrific, and there followed several years of inaction.

Nevertheless, at the convention of the A. F. of L., in 1889, the lull was broken and it was decided to proceed with the eight hour campaign. One union at a time was to make the attempt until eight hours had become the universal work day. The Brotherhood of Carpenters and Joiners was chosen to call an eight-hour strike on May 1, 1890. Samuel Gompers addressed a request to the International Labor Congress, meeting in Paris, to Aid the movement by calling mass meetings and demonstrations throughout Europe. The congress granted the request. The eight-hour strike was declared. More gains were made for eight hours in the building trades and great demonstrations of solidarity and support were staged throughout Europe. From then on May Day has been kept sacred by the militant European workers.

But what happened in the United States? After one more unsuccessful attempt, with the miners in the leading role in 1891, the eight hour movement was abandoned. The militancy of the American Federation of Labor was dead. May Day was forgotten. In 1894, the United States congress enacted a law declaring Labor Day a holiday in the District of Columbia and the Territories. Perhaps the memory of May Day, 1888 and the fear that that day would come to be a tradition in this country as it had already become in Europe had something to do with this decision. The A. F. of L. was satisfied. This gift of the bosses fitted with the slogan, “A fair day’s work for a fair day’s pay.” The perfunctory annual observation of an official holiday began, and May Day was left to the revolutionary section of the American labor movement to keep alive.

From time to time, in various localities, Labor Day parades and celebrations have taken on a militant hue. They have occasionally been genuine workers’ demonstrations, occurring in the midst of struggle, and serving as a means to unite masses of workers for a single purpose. But these occasions have been rare, For the most part, Labor Day parades are routine affairs conducted in each city by the central labor body which appoints a committee to arrange a parade and usually a picnic for it to wind up in. The speeches are the flat, colorless and highly eulogistic type of oratory, that slightly altered and spoken by different (but not always) persons, are heard on the Fourth of July or Decoration Day.

During the war, notably in the year 1918, Labor Day was used by officials of the American Federation of Labor as an occasion to rally the to “help win the war.” The day was made over into a militaristic demonstration on behalf of the “War for Democracy.” The American Federation of Labor officialdom and all the little petty officials were hand in glove with J. P. Morgan trying to win an imperialist war. Since that time, Labor Days have been hardly less servile in spirit, although they of course lack the blood and thunder of that disgraceful spectacle.

In recent years many local labor bodies have lost even the incentive to arrange parades on the day. In Chicago, for example, the question of a parade has been a disputed question. There has been no parade for five years. In several more years Labor Day promises to be nothing more than a mere bank holiday.

Such, in brief, is the record of Labor Day. Indeed, Labor Day has traced from year to year, a veritable picture, of the A. F. of L. Today the effete Labor Day of 1926 epitomizes the effete A. F. of L. of 1926. It is not our present job to go into the why of it. It is enough to say that the end of the militancy of the official labor movement approximates the beginning of the United States on its career as an imperialist capitalist power.

New blood is needed. The present officialdom of the American Federation of Labor is a dead and bloodless hand guiding a movement grown sluggish thru too much patronage from the master class.

And that new blood, when it cuts off the dead band and revitalizes the American Federation of Labor with the fighting traditions of its youth and the fire of struggle, will transform even Labor Day into a day of demonstration against capitalism, and will also observe in a real militant way the day of international working class solidarity—May Day.

The Daily Worker began in 1924 and was published in New York City by the Communist Party US and its predecessor organizations. Among the most long-lasting and important left publications in US history, it had a circulation of 35,000 at its peak. The Daily Worker came from The Ohio Socialist, published by the Left Wing-dominated Socialist Party of Ohio in Cleveland from 1917 to November 1919, when it became became The Toiler, paper of the Communist Labor Party. In December 1921 the above-ground Workers Party of America merged the Toiler with the paper Workers Council to found The Worker, which became The Daily Worker beginning January 13, 1924. National and City (New York and environs) editions exist

PDF of full issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/usa/pubs/dailyworker/1926/1926-ny/v03-n200-supplement-sep-04-1926-DW-LOC.pdf