Capitalism made Thomas Kennedy, and his many skills, obsolete as machines removed workers from the metal mills. And so it goes.

‘Banishing Skill from the Foundry’ by Thomas F. Kennedy from the International Socialist Review. Vol. 11 No. 8. February, 1911.

METAL founding is one of the old mechanic arts. Indeed in some of its branches it may lay claim to being something more than a mechanic art.

Castings may be made of any metal that can be reduced to a liquid state without vaporizing. About 150 years ago it was discovered that iron could be cast. Up till that time the chief object of the founder’s art was copper in its various combinations with tin and zinc, forming brass and bronzes. And these metals still furnish the raw material for an important branch of the foundry business. Where lightness combined with strength is required, steel castings are displacing iron, but iron still remains by far the most important foundry metal.

The molder capable of doing the finest work has in him the makings of an artist. He must have eye as true, touch as sure and light and hand as supple and sensitive as any wielder of brush or pencil. He must have imagination, the parent of invention, because every difficult, intricate job requires, if not invention, at least ingenuity. The gradation in the character of the product from a grate bar to the statue of a Greek God are as marked as the gradations from painting a fence to painting a landscape.

The manner in which the foundry resisted the efforts of inventors bears witness to the difficulties encountered, and is corroborative of my’ contention that in some of its branches, it is more than a mechanic art. It withstood so long the assaults of the inventors that molders had come to feel like some other craftsmen that, “You can’t put brains into a machine.”

Long before I went into a foundry, twenty-seven years ago, efforts had been made to substitute mechanical contrivances for the hand and hand tools of the molder. Up until that time, and for long after, these attempts merely furnished amusement and a little mild excitement for the molders. In nearly every specialty foundry there was a tradition of the trial and failure of machines, and often they could be seen rusting in the yard. In one case a molder challenged, raced with and beat a machine making molds. Nevertheless the machine won—for’ its owner— because in beating it, the molder had established a new and more rapid pace.

Out of all this effort and experiment the “match plate,” the “stripping plate and the “squeezer” were evolved years ago. They were all old when I went to work in the foundry. All modern molding machines are merely adaptations of these old inventions.

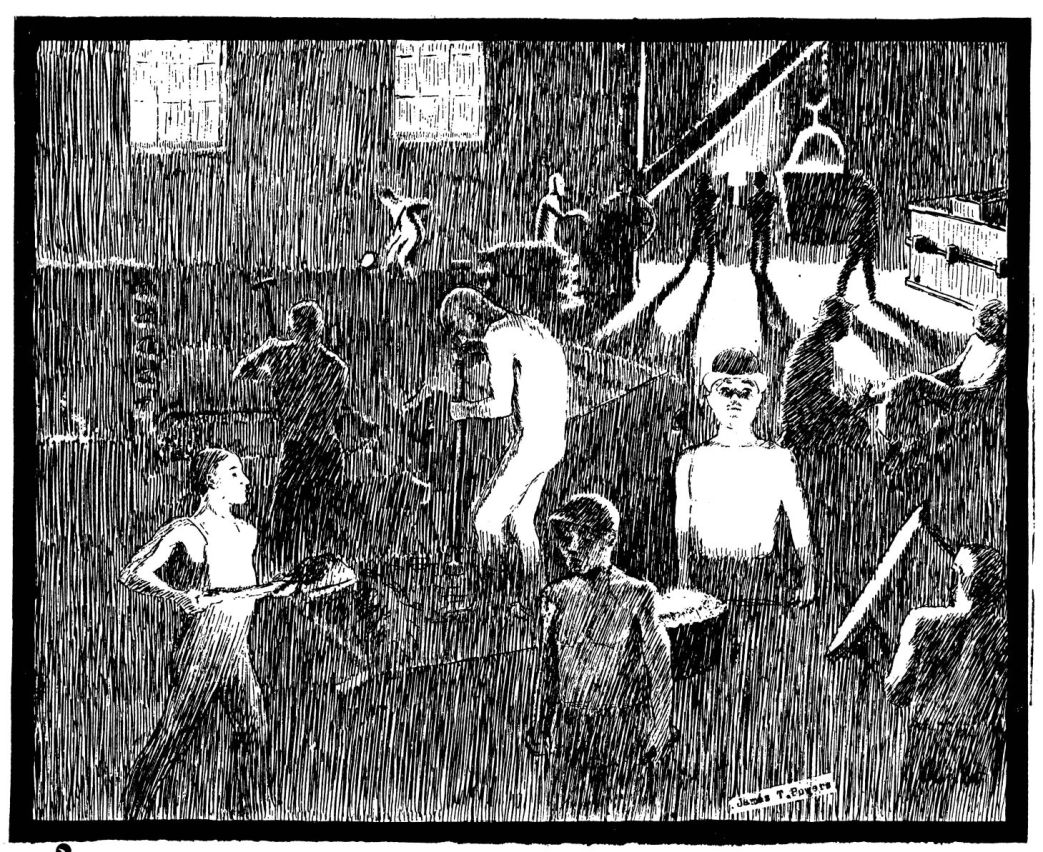

Machines introduced in other industries, while they did not lighten the work, at least did not make it harder. No occupation has connected with it more hard work requiring great muscular exertion than metal founding. The early machines never aimed at this work. They were designed to eliminate skill and were not labor saving machines. They not only left all of the hard slavish drudgery to be done as before but increased it. To this very hour most of the machines added to foundry equipment while increasing enormously the output per “hand” have done so only by forcing the “hands” to greater exertions. In addition to forcing them to greater exertions the machines have reduced the relative and actual earnings and lowered. the economic status of the foundry “hand.”

It is not therefore surprising that foundry workers, collectively and individually, organized and unorganized were a unit in opposition to “improvements” that did them such irreparable injury, injured them by decreasing their earnings, lowered their status and increased their burden of toil.

This perfectly justifiable hostility on the part of the molders was a factor in retarding the development and adoption of the machines. But powerful economic forces beyond the control of either molders or foundry owners were creating conditions which made it ever more profitable to add molding machines to foundry equipment. So in they went and in they are still going in increasing numbers despite the feeble resistance of the molders.

Some six or seven years ago a national convention of the Molders’ Union went on record declaring that the union was not opposed to molding machines. At the same convention they let down the bars so that machine operators can now become members of the Molders’ Union. But this official action in nowise altered the feeling and attitude of the workers in the shops who had to compete with the machines. The admission of machine operators—who are not molders—to the union is an illustration of the solidifying power of the machine which I will deal with in another article.

The old “stripping plate” and the still older “match plate” provided the mechanical principles out of which grew the modern molding machine. They are in fact only pattern devices, and it is taking a rather unwarranted liberty with the word to call them machines. From a purely mechanical standpoint their application is unlimited, but there are practical considerations which fix their limitations. One consideration is the size of the casting, another is the intricacy. But even though size and other features are favorable, unless there is a large number to make it would not be profitable to rig the job for a machine.

A number of forces have been at work creating this necessary condition. For one thing, the world is growing in population and wealth and there is a greater demand for machines. A great many machines and other commodities have reached such a state of perfection that nothing short of a revolutionary discovery or invention can bring about any general alteration in design or construction. Such articles and the castings required for them, can be standardized. The foundry manager when putting in new patterns of a standard design which are to be made for an indefinite time, need not hesitate at first cost as he would if the castings were to be made for only one or two seasons. The merging of big financial interests controlling hitherto competing concerns by standardizing and in other ways helps to produce the right condition for the development of machines.

“Match plates” and “stripping plates” have been in use on a small scale ever since they were invented, but for the reasons I have pointed out never came into general use. With the great revival of business in 1899 duplicates of each casting were needed in larger numbers than ever before; molders’ wages were advancing; pattern “making and pattern making tools had been almost perfected; and corporations were richer and in better condition to carry on expensive experimenting operations than ever before. All things were favorable to the development of molding machines and this period marks the beginning of a new era in the foundry business.

At first the molders were inclined to scoff. Those engaged upon the more intricate and difficult jobs in particular felt perfectly safe. They felt that while they might do the plain jobs on the machines they could never make the difficult ones until they could put brains into the machine. The scoffing soon turned to mourning as they saw their favorite jobs being made by unskilled laborers on “stripping plate” or “match plate” machines.

As a rule the more difficult the job to mold the greater the profit in rigging it for the machine. Hence it was the jobs made by the very best mechanics that were first attacked. In the case of a plain casting the machine might only enable the unskilled laborer to make as many molds as the skilled molder, while on some of the more difficult jobs it would enable the laborer to make as many as five molders.

One job of which a strong, competent molder made four in a day, two laborers made forty-five when rigged for the “stripping plate.” The molders for years had made seventeen a day of a certain job; now three unskilled laborers made two hundred and twenty-five (225). Only a molder or a person familiar with foundry practice who has seen made the most intricate castings could appreciate the finest points about the “stripping plate.” From amongst all of its features I select cone as an illustration to show its advantages; to show why a laborer, doing all of the hard work formerly done by the molder—the shoveling, riddling and ramming—can still produce so many more castings in the same length of time.

To secure castings against the wash of the metal, in common with every molder, I have spent hours setting small finishing nails in some small “bead” of sand in a mold; then sprayed or brushed it with a mixture of water and molasses and perhaps dried it with a gas flame. Castings with such “beads” are now made on the machine without nails, molasses water or drying.

In one foundry in Pittsburg, where I worked for many years, there was 100 bench molders in 1901. Now, with the output on that class of work nearly doubled, there is less than ten left.

The possibilities of the “stripping plate” and adaptations of the “match plate” are only now becoming generally known to foundry men, and conditions are just ripening for their development. Of the tens of thousands of small and medium. sized castings produced every year which might be made on machines, only a few have as yet been touched.

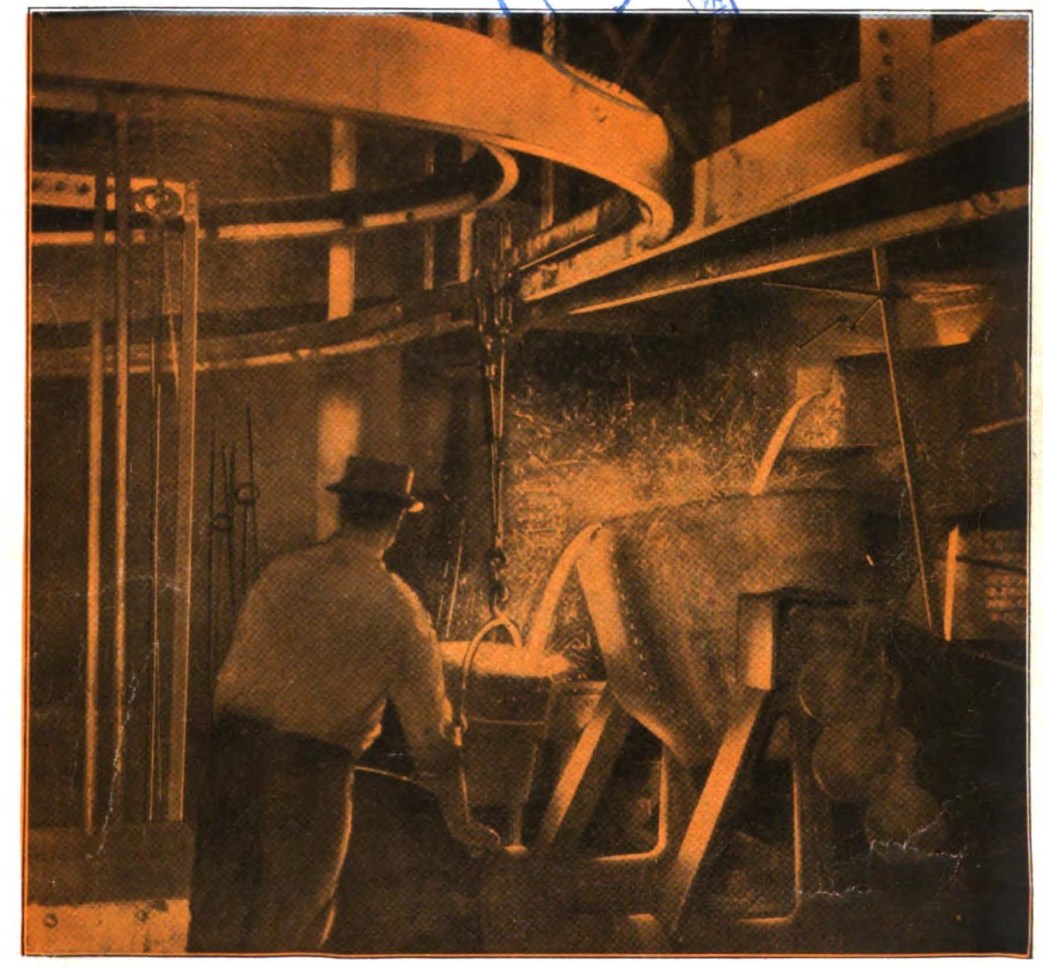

Only by the adoption of the continuous heat can the foundry machines already tested and of proven merit be utilized to the best advantage. Only a few foundries in the world run continuous heats. One of these few and the first to introduce the real labor-saving machinery was the Westinghouse Airbrake at Wilmerding, Pa., about which I shall tell in a later article.

The International Socialist Review (ISR) was published monthly in Chicago from 1900 until 1918 by Charles H. Kerr and critically loyal to the Socialist Party of America. It is one of the essential publications in U.S. left history. During the editorship of A.M. Simons it was largely theoretical and moderate. In 1908, Charles H. Kerr took over as editor with strong influence from Mary E Marcy. The magazine became the foremost proponent of the SP’s left wing growing to tens of thousands of subscribers. It remained revolutionary in outlook and anti-militarist during World War One. It liberally used photographs and images, with news, theory, arts and organizing in its pages. It articles, reports and essays are an invaluable record of the U.S. class struggle and the development of Marxism in the decades before the Soviet experience. It was closed down in government repression in 1918.

PDF of full issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/usa/pubs/isr/v11n08-feb-1911-ISR-gog-Corn-OCR.pdf