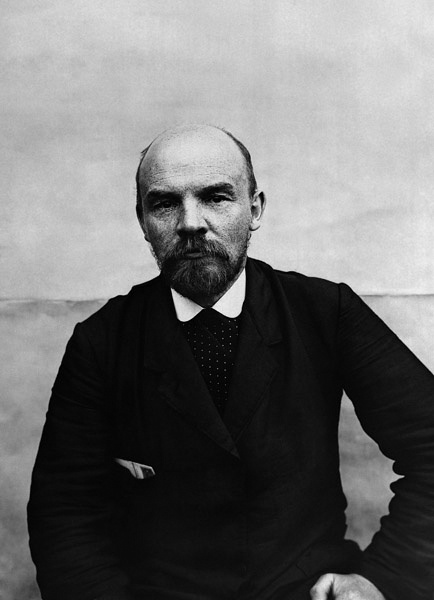

‘Lenin on War’ by Karl Radek from The Daily Worker (Magazine Supplement). Vol. 2 No. 98. July 12, 1924.

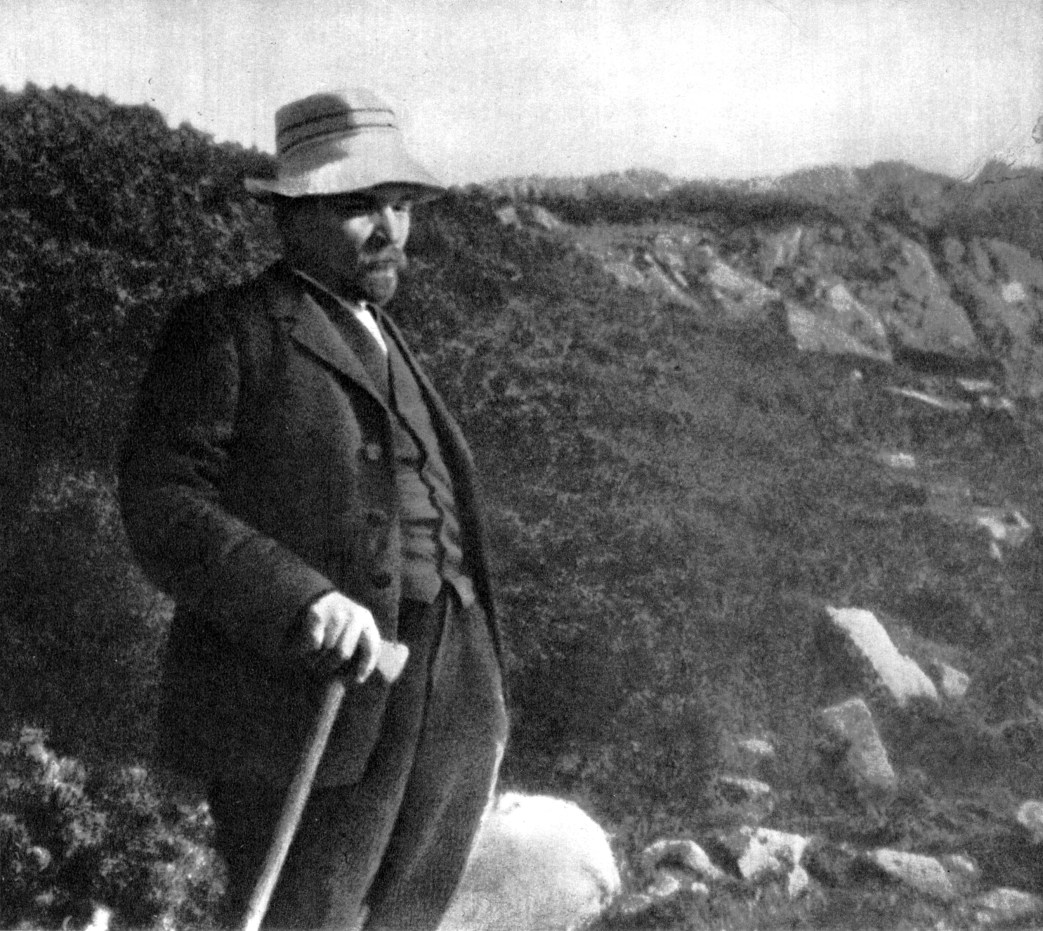

The war breaks out. The dark day comes, the 4th August Lenin, sojourning in the Carpathian district receives the news of the complete betrayal by German and international Social Democracy. In the first moment he doubts the tidings, and hopes that it is merely a war manoeuvre of the international bourgeoisie; but he is speedily convinced of its tragic truth, goes to Switzerland, and takes up his fighting position at once. As early as the end of 1914, I had the opportunity of speaking with him, after his attitude had been firmly established in the historic manifesto issued by the Central Committee of the party, and in various issues of the “Social Democrat.” I still remember very well the profound impression made on me by the conversation with Lenin. I came from Germany for the purpose of establishing connections with the revolutionary groups of other countries. In Germany we unconditionally rejected the attitude of the social democratic majority from the very first day onwards. We rejected the idea of the defense of native country in an imperialist war. We were in conflict with Haase and Kautsky, who went no further than diffident opposition to the social patriotic leadership of the party, and only differed from this in sighing for peace. In our propaganda, carried on in the censored press and in hectographed papers, we agitated for revolutionary war against war. But for me—and thru my intermediation also for many German comrades—my conversation with Lenin signified a sharp turn to the left. The first question which Lenin put to me was the question of the prospect of a split in the German Social Democracy.

This question was like a dagger stab to the heart to me, and to the comrades standing at the left wing of the party. We had spoken thousands of times of reformism as of a policy pursued by the workers’ aristocracy. But we hoped that the whole German party, after the first patriotic throwback, would develop towards the left. The fact that Karl Liebknecht did not vote openly against the war on August 4, is to be explained precisely by the fact that he still hoped that the persecution carried on by the government would Induce the whole party to break with the government, and with the defense of the imperialist fatherland. Lenin put the direct question; what is the actual policy being pursued by the Second International? Is it an error, or is it treason to the working class? I began to explain to him that we were on the borderland between the period of peaceful development of socialism and the period of storm and stress, that it was not merely a question of treachery on the part of leaders, but of the attitude taken by masses not possessing the power to offer resistence to the war, but subservient to the bourgeoisie; but that the burdens imposed by this policy would force the masses to break with the bourgeoisie and tread the path of revolutionary struggle. Lenin interrupted me by the words: “It is an historicism that everything finds its explanation in the changing epoch. But is it possible for the leaders of reformism, who led the proletariat systematically into the camp of the bourgeoisie even before the war, and who openly went over to this camp at the moment of the outbreak of the war, to be the champions of a revolutionary policy?” I replied that I did not believe this to be possible. “Then,” declared Lenin, “the survivals of an outlived epoch, in the form of reformist leaders, must also be cast aside. If we want to facilitate for the working class its transition to the policy of war against war, of war against reformism, then we must break with the reformist leaders, and with all who are not fighting honorably on the side of the working class. It is only a question of when this rupture is to be accomplished.

The question of the organizatory preparation of this rupture is purely one of tactics, but to strive towards rupture is the fundamental duty of every proletarian revolutionist.” Lenin insisted on the sharpest form of the ideological struggle against the social patriots, insisted on the necessity of openly emphasizing the treachery committed, especially the treachery of these leaders. He frequently repeated these words on later occasions, when we were working together; when drawing up resolutions he invariably adhered to the standpoint of this political definition, and held it to be a measure of revolutionary sincerity and logic, an evidence of the will to break with Social Democracy.

Lenin insisted with equal emphasis upon the slogan of civil war being opposed to the slogan of Burgfrieden (civil peace). Since our polemical discussions with Kautsky, we left radicals- in Germany had become accustomed to formulate the slogan less clearly; our slogan was the slogan of “mass action”. The lack of clearness of this slogan corresponded with the embryonic condition of the revolutionary movement in Germany in the years 1921 and 1912, when we regarded the demonstration made by the workers of Berlin in the Tiergarten, at the time of the struggle for universal suffrage for the Prussian Diet, as the beginning of the revolutionary struggle of the German worker. Lenin showed us that though this slogan e suitable for the purpose of opposing the action of the masses to the parliamentary game played by the social democratic leaders before the war, it is entirely unsuitable in a period of blood and iron, in a period of war. “When discontent with the war has increased” he said “then the Centrists can also organize a mass movement for the purpose of exerting pressure on the government, and for forcing it to end the war with a peaceful understanding. If our goal, the goal of ending the Imperialist war by the revolution, is not to be a mere pious, wish, but a goal for which we really work, then we must issue the slogan of civil war, clearly and determinedly.” He was extraordinarily pleased when Liebknecht, in his letter to the Zimmerwald conference, made use of the words; “Against the civil peace for the civil war”. For Lenin, this was the best proof that Liebknecht was in agreement with us in essentials.

The split in the Second International as a means for the development of the revolutionary movement in the proletariat, civic war as the means of victory over imperialist war these were the two leading ideas which Lenin endeavored to Impress upon the minds of the advanced revolutionary elements of every country with which he was in connection.

The Saturday Supplement, later changed to a Sunday Supplement, of the Daily Worker was a place for longer articles with debate, international focus, literature, and documents presented. The Daily Worker began in 1924 and was published in New York City by the Communist Party US and its predecessor organizations. Among the most long-lasting and important left publications in US history, it had a circulation of 35,000 at its peak. The Daily Worker came from The Ohio Socialist, published by the Left Wing-dominated Socialist Party of Ohio in Cleveland from 1917 to November 1919, when it became became The Toiler, paper of the Communist Labor Party. In December 1921 the above-ground Workers Party of America merged the Toiler with the paper Workers Council to found The Worker, which became The Daily Worker beginning January 13, 1924.

PDF of full issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/usa/pubs/dailyworker/1924/v02a-n098-supplement-jul-12-1924-DW-LOC.pdf