A fantastic on-the-scene account from Phillips Russell on the battles following from the Bread and Roses strike of 1912, a fight which would help define labor radicalism before the war.

‘The Second Battle of Lawrence’ by Phillips Russell from The International Socialist Review. Vol. 13 No. 5. November, 1912.

THE proletariat, the lowest stratum of society, cannot stir, cannot raise itself up, without the whole of official society being sprung into the air.”

When Marx put that in the Communist Manifesto he certainly knew what he was talking about. It’s the truth; for the proletariat around historic Lawrence has been stirring again, feeling its muscle and testing its power, and the result is that the upper strata have not only been sprung into the air but have hit the ceiling with a loud bang.

This article has to be written here in Lawrence on the eve of the Columbus Day “parade of patriotic citizens, which has been gotten up and arranged by Mayor Scanlon, the Catholic priesthood, and the American Woolen Company. None knows what the morrow may bring forth. There have been ten days of tension and everyone who is alive to the situation is aware that Lawrence is sitting on a volcano whose repressed forces may break out at any moment. The suspense will last until Monday morning when the Ettor-Giovanniti trial is resumed. Before that time there may be violent scenes in the streets; or the whole affair may blow off in the cheers, music and speeches of tomorrow. There is no veil over the class struggle here tonight. The chasm between the bourgeois and the working class is wide and deep and there is no disposition on either side to bridge it or to smooth it over.

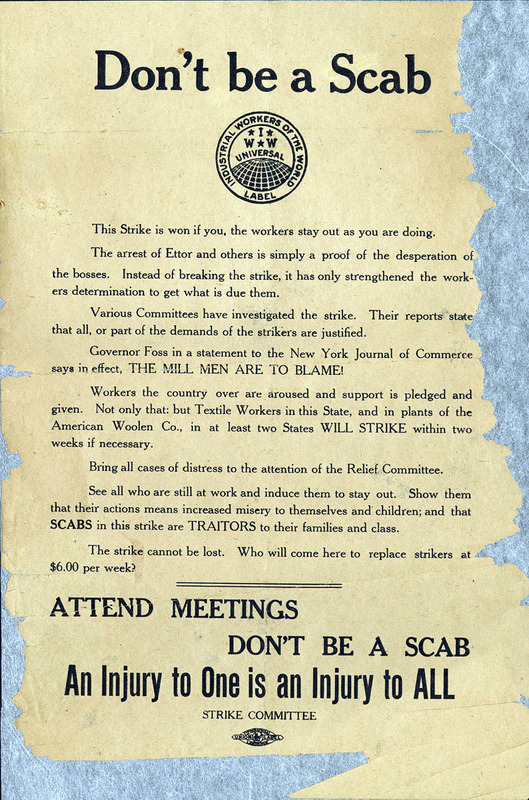

No one who has not seen a situation of the kind before can imagine into what a frenzy the highly respectable business and professional element in their hatred of the I.W.W. have worked themselves into.

All this murderous hatred has been aroused because trade has fallen off, because business has been interrupted, because profits have been cut into; in short, because the capitalist system of this locality, the whole profit-grinding machinery, has been seriously upset, disarranged, and for a time put out of order. There is no blacker crime in the eyes of the capitalist class, from the petty tradesman to the head of a great corporation. Consequently war to the death has been declared against the Industrial Workers of the World, and there are threats of tar and feathers, of forced departures from town, of torture and assassination.

A strike for improved conditions is not new in this country. It is comparatively easy to enlist a host of workers in a war for bread, but a strike for an immaterial thing, a cause, an ideal, is a horse of another color. Is there any considerable body of workers in the United States who will go on strike for a principle? A month ago this question might have been answered skeptically, but not so now.

On the 30th day of September last the mill workers of Lawrence came out in the first mass protest strike we have had in this country, thereby marking the beginning of a new era in American labor history. From now on Revolutionary Unionism is a fact that the capitalist class of this country must consider and deal with.

The second Lawrence strike was called as a protest against the imprisonment and trial of Ettor and Giovanniti and broke out spontaneously in the Washington mill on Thursday afternoon, September 26, despite the letters sent from jail by the two agitators advising the workers against such a strike. It grew in volume until by Saturday 12,000 people were out, crippling the~ Wood, Ayer, Everett, Arlington and Lower Pacific mills.

By a vote taken at a general open-air mass meeting held on the following Saturday afternoon it was decided that all should cease work until Tuesday morning.

Sunday a memorial parade was held in honor of Anna La Pizza and John Rami who lost their lives in the strike of last winter. Sunday morning a special train brought several hundred workers from Boston and nearby towns. A huge throng was at the station to meet them and as banners were unfurled, one of the bands struck up and the great mass of workers moved up the street towards Lexington Hall where the parade was to be formed.

Up to this time there had been no disorder, no disturbances of any kind whatever. Such a state of affairs, of course, could not be permitted to continue. The I.W.W. had the name of being a violent organization, therefore it must be made to appear violent. The police had already made objections to the music and to the banners, but to no avail.

Now it might have been better if no bands had played and if no cheers or yells had been indulged in. It might have been more impressive to proceed in silence through the streets ; but the fact is the bands played, and the respectable New England eye and ear, not knowing that bands of music for funerals are not uncommon among the people most numerous in the throng, was revolted by the spectacle. The police sergeant on duty was shocked. The turning of the marchers from Broadway into Essex street, which the police claim was not permissible, furnished an excuse.

We were all leaning out of the windows of the Central building watching the advancing host when suddenly a big squad of police ran hastily out of a side street, deployed, and spread in a solid line across Essex street squarely in the path of the scattered mass of approaching workers. It was perfectly evident that there was going to be trouble and it was going to occur right beneath our windows.

I never saw a worse scared bunch of cops. Many of them were young fellows and this was probably their first dirty job. Their faces were white, they gripped their clubs nervously. The advancing crowd no doubt looked mighty dangerous, with their red banners flying, and Carlo Tresca, a bull of a man, at the head.

The gap between the line of police and the marchers steadily lessened and then closed. There was a moment’s hesitation as a police sergeant shook his club furiously in Tresca’s face and shouted something at him. Tresca evidently did not understand and threw up one hand as a signal for the crowd to stop. It was useless. The pressure from behind was too great. In another second Tresca was forced through the line of bluecoats and two of them closed with him. Instantly the police line was ripped to pieces like a rope of sand and the old, old, sickening spectacle was presented of burly and well-armed policemen raining vicious blows down upon the unprotected heads of uncomprehending workingmen. Blood was soon flowing, but it was not all confined to one side. Tresca was taken into custody twice but for some mysterious reason was never arrested or taken to the station house, and while all the capitalist papers had him fleeing the city “in terror of the vigilantes” he was walking the streets as if nothing had happened.

Sunday afternoon the memorial parade contained perhaps 15,000 workers. Innumerable flags and banners were carried, one of which was the subject of much controversy. This was a sign in black and white headed: “No God, No Master,” and furnished the theme for violent sermons by the local clergy afterwards.

The next day Ettor, Giovannitti and Caruso were placed on trial for their lives in Salem because their “inflammatory speeches” are alleged to have caused the death of Anna La Pizza in a street disturbance last winter. That day the workers һаd tied up the American Woolen Company’s mills as a protest. Police and hired strong-arm men were on the job as usual and trouble followed, also as usual. Nothing unusual occurred when Ettor, Giovannitti and Caruso were summoned before the judgment seat of High Capitalism, the only feature being the extraordinary number of excuses that the 350 talesmen gave for not serving on the jury. As the weary examination of jurors proceeded, there was but one thing that impressed the spectator and that was the fact that in their courts the capitalists have erected an elaborate and intricate piece of machinery that the working class never can use. Thank whatever gods may be, the time is coming when the rising workers will sweep the whole miserable business out of existence Wednesday afternoon the trial was halted until few talesmen could be summoned and as we came out of the courthouse City Marshal Lehan was showing to the reporters a telegram from Vincent St. John, general secretary of the I.W.W. at Chicago, informing Lehan that he would be held responsible for the safety of Bill Haywood on account of the fact that a gang headed by one William Seid or Seiden had left New York that day for the purpose of doing him injury. Lehan scoffed at the telegram but he was careful to assign a plain clothes man to keep near Hay wood, who had been watching the trial all day. The information that St. John sent was circumstantial and came from a source that ought to be reliable. When’ Haywood returned to Lawrence that night he found a bodyguard waiting for him that insisted upon taking him in charge. It was composed of two Italians, one Portuguese, and one Syrian and they never left him out of their sight until he announced that he thought he had been guarded enough.

It was evident that a change had taken place in Lawrence. Cops stood guard at every corner and plain-clothes men and “bulls” of every description sauntered about the streets. Groups of men stood in the shadows and conversed in low tones. The Lawrence papers, which hitherto had maintained an appearance of impartiality, now carried double-column editorials on their front pages demanding that the “cancer of anarchy” be cut out of their midst, with demands for the formation of vigilantes’ committees. “They did it in San Diego,” said one paper, “and we can do it here in Lawrence.”

The Boston papers which had given many of the actual facts about police brutality during the protest strike were loudly denounced and an official statement by Mayor Scanlon was given great prominence. This was as follows:

“I approve most heartily every action of the police today. They did nothing more than the conditions warranted. They were perfectly justified in using their clubs as they did. Are we going to allow our city to be run by outside thugs? The police did not do half enough. The papers have lied about us and continue to tell false statements about our city. I am proud of the actions of the police.

We who live in this city cannot longer bear the conditions now existing. This thing will be cleared up if we have to get 100 more “clubbers.”

Mayor Scanlon afterward became frightened at the sound of this and tried to pretend that he said “100 more coppers.” But what he said was “clubbers.” There were plenty who heard him.

Thursday night a “citizens’ mass meeting” was held in the city hall, and if I.W.W. speakers had used half the language indulged in by these “foremost” citizens the entire country would have arisen the next day and demanded that these bloody agitators be hanged. Among the orators were a mayor, a Catholic priest, a Protestant preacher, a schoolteacher, a congressman, an assistant municipal judge, a clubwoman, and a prominent business man. More vitriolic, more venomous speeches, more vindicative appeals to class hatred, were never made by the most rabid throng of so-called anarchists. Listen:

Mayor Scanlon said: “We will not countenance this red flag of anarchy in our midst.”

Mr. Bradley, who acted as chairman said: “The war of 1776 began this union. The war of 1861 was to perpetuate this union, and the war of 1912 is to protect the interests of this nation.”

Postmaster Cox said: “Men have come who have filled these people with riot and anarchy. Now that business has got to stop, and it’s going to stop right now.”

Mr. Chandler said: “If the militia cannot put this down, they know where they can get others to help them. And also, I say to you, these people must be ejected, legally, if possible, but ejected from our doors.”

Congressman Knox said: “These conditions remind me of Captain Parker in the Revolutionary War. He said, if they want war, let it commence right now, and that is what I say.

Mr. Chandler is also quoted as saying: “We are ready to assist in the annihilation of these malefactors.”

The Rev. Lovejoy, pastor of the So. Lawrence Congregational Church, said: “There is no room for the red flag in this country, and we will not tolerate it.”

Father O’Reilly, shouted: ‘”Those who do not want to work better take a hint and go. We will drive the demons of anarchism and socialism from our midst.”

Mayor Scanlon then announced that Columbus Day had been selected for a “God and Country” parade in which all patriotic citizens would be expected to join. He issued a further ukase to the effect that all good citizens should wear an American flag on their coat lapels until Thanksgiving Day.

When the crowd poured out of city hall late that night it was plain that they needed but a spark, a wave of the hand, or a leader, to turn them into a mob о: murder and riot. They had been cunningly worked up into a fury of excitement and the small knots of people whom one passed on the street talked gloatingly of tar and feathers, of red-hot pokers, and lamp-post lynchings. Evidently the class struggle as it becomes sharper from now on is to be no tea-party affair.

The I.W.W. was not slow in taking note of these threats and issued a statement in reply, saying that if the least of its members was injured or killed, the speakers named above would be held responsible.

At the same time Lawrence entered upon such an orgy of patriotism as few cities have passed through. The American flag was put to all sorts of ridiculous and degraded uses, from being worn as the cover of an umbrella by a grafting politician to being stuck on the tail-board of the city dump carts. American flags, large and small, were imported into the city by the thousands and all that could not be sold were given away. Any man seen without a flag on his person was likely to be stopped and insulted by street hoodlums.

The most alarming and impossible stories were set afloat. Haywood was an especial target. The Boston Journal appeared one day with a picture of Haywood wearing a U.S. flag on his coat lapel. It was a pure fake and so aroused William that when the reporters came round again he told them with considerable vigor that while he was not opposed to the American flag, that he was not going to be forced to wear one at any politician’s dictation, particularly when said politician’s citizenship was in question. This was a back-handed slap at Mayor Scanlon whom common rumor says has never even taken out his naturalization papers. Another local paper announced that Haywood was known to be worth $250,000, which piece of information so pleased his friends that they all gathered round and requested a loan in concert. The flag fever continued unabated but without noteworthy incident until Mayor Scanlon came out with a new statement saying that not only was the I.W.W. not wanted in the parade of patriots, but would not be allowed to take part at all.

The I.W.W. was so hurt by this that they went off in a huff and announced a little affair on their own account, this being a picnic at Pleasant Valley on the day of the patriotic parade.

So if there are any more street clashes it will be up to the respectable citizens of Lawrence to explain.

Later Note—Up till an early hour on Saturday night, October 12, Columbus Day has passed without any disturbance. The patriots paraded gloriously today to the number of 30,000, according to claims, but if it had not been for the army of school children it would have been a sorry showing. Every parader carried an American flag and some a half dozen. No other flag was allowed in the parade, not even an Italian one, though it was Columbus Day. Across Essex street, near the Central building, an arch of banners was spread with the following inscription, written by Father O’Reilley and Attorney Dooley, in big, black letters:

“FOR GOD AND COUNTRY. The Stars and Stripes Forever. The Red Flag Never, A Protest against the I.W.W. Its Principles and Methods.”

This is the greatest compliment ever paid to a labor organization by a municipality in the history of the world. The I.W.W. ought to be proud of itself.

The day was cold and rainy, but early this morning a little band of 200 of the faithful made the long hike, three miles, out to Pleasant Valley and resolved to have a picnic or bust. By noon the crowds began to come and by 2 o’clock there were 4,000 revolutionists present despite the rain, and the muddy roads. Haywood, Fred Heslewood, Gurley Flynn. Archie Adamson, Tresca, Ex-Mayor Cahill, and several speakers in foreign languages addressed the throng and none of them ever made better speeches in their lives. Every nationality was represented and all pledged themselves anew, with a mighty shout, to One Big Union.

The International Socialist Review (ISR) was published monthly in Chicago from 1900 until 1918 by Charles H. Kerr and critically loyal to the Socialist Party of America. It is one of the essential publications in U.S. left history. During the editorship of A.M. Simons it was largely theoretical and moderate. In 1908, Charles H. Kerr took over as editor with strong influence from Mary E Marcy. The magazine became the foremost proponent of the SP’s left wing growing to tens of thousands of subscribers. It remained revolutionary in outlook and anti-militarist during World War One. It liberally used photographs and images, with news, theory, arts and organizing in its pages. It articles, reports and essays are an invaluable record of the U.S. class struggle and the development of Marxism in the decades before the Soviet experience. It was closed down in government repression in 1918.

PDF of full issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/usa/pubs/isr/v13n05-nov-1912-ISR-gog-ocr.pdf