The T.U.U.L.-affiliated (Cannery) and Agricultural Workers Industrial Union first tried to organize the agricultural workers of the Imperial Valley in early 1930 in a failed strike led to the imprisonment of key militants and a break-up of the organization. Returning in November, 1933 for the lettuce harvest during a wave of other strikes, mostly led by the CAWIU washed through California’s growing regions in 1933 and 34. Here, a report of the beginning of the Bawley lettuce strike, largely by Mexican migratory workers.

‘Blood on the Lettuce’ by Michael Quin from the New Masses. Vol. 10 No. 4. January 23, 1934.

AN INCREASING wave of terror is is rolling down the Imperial Valley as the seven thousand lettuce field workers enter the second week of their strike. At this writing, Jack Henry, representative of the International Labor Defense, has disappeared; communication has been stopped between various towns in the strike area; Grover Johnson, the I.L.D. attorney from San Bernardino, reports that everyone who speaks to him is instantly arrested. The Mexican consul is actively carrying on the role of a strike-breaker.

The press is carrying scare headlines stating that the strikers are arming. Actually, the growers have marshalled every weapon of violence against the strikers, and the picket lines are being maintained at the cost of a constant battle.

The lettuce fields are not the only scene of strike struggle in Southern California. To the seven thousand lettuce workers must be added twelve hundred Los Angeles milk industry workers, and five hundred citrus workers in San Bernardino; there is also a strike on among San Pedro fishermen.

Violent class struggles in California have ripened with every crop during the past year as well as in every major industry. In many cases these struggles have developed into virtual warfare between the owners and the workers. In every case, laws and justice, or any semblance of orderly settlement have been discarded by the owners in efforts to decide matters in their own favor by arbitrary force. Police forces, aided by vigilante committees and the American Legion, have been used in gangster fashion with no regard for their supposed function. The recent lynching in San Jose, condoned by Governor Rolph, was by no means an isolated incident. It typifies and is part of the general abandonment of the law that has been encouraged throughout the State. The Governor’s approval not only related to the lynching, but was a general approval of the vigilantes and gangs of ‘hooligans’ employed by industrialists throughout the State to terrorize striking workers and enforce starvation wages.

The Imperial Valley lettuce fields, harboring some of the worst labor conditions in California, has been the scene of so many struggles during the past eight years, all of increasing violence, that the growers prepare for the picking season by organizing their terror in advance. Organization among the workers prior to any protest or demand must be carried on with the utmost secrecy. Underground tactics must be resorted to which can be compared only to the conditions prevailing in Fascist Germany. Any worker participating in the organization of a union is eligible to arrest. As far back as 1930, seven workers were railroaded to San Quentin and Folsom prisons for no other act than seeking to organize the agricultural workers.

This year the growers set a wage averaging from ten to twenty-two cents an hour for work performed under the most miserable conditions. On Jan. 8, at six o’clock, three thousand workers under the Cannery and Agricultural Workers’ Industrial Union went out on strike. By noon the next day their number had increased to five thousand. At the time of this writing there are seven thousand workers striking and there is every prospect that the seed workers will join them.

The demands are: thirty-five cents an hour for pickers and packers, fifty-five cents an hour for crate makers and shed workers, four cents a crate for shed packers and equal pay for equal work for women and young workers. Also, recognition of the union, all hiring to be done through the union, guarantee of five hours work when a worker is called, free transportation, free clean drinking water and abolition of the contract system.

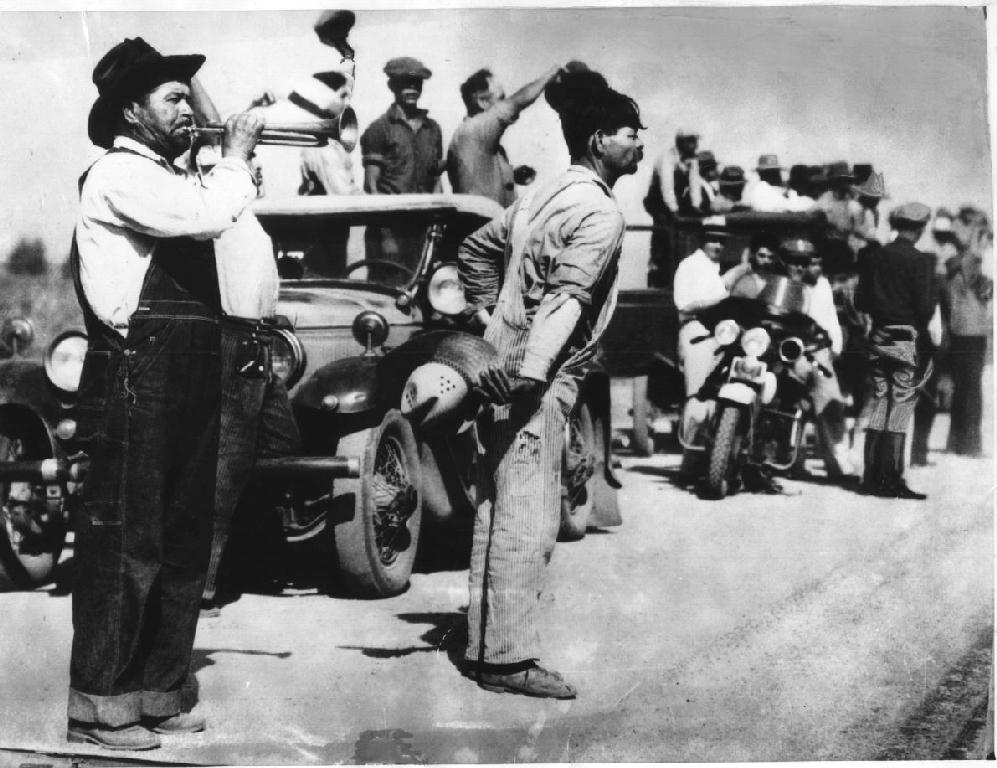

Strong picket lines have been maintained by the workers in the face of vigilante attacks and hundreds of arrests. All towns in the strike region, Holtville, El Centro, Brawley, and Calexico are surrounded by armed guards. Hundreds of legionnaires have been deputized. It is as difficult to approach the valley as to penetrate a war zone. All roads are patrolled by scores of motorcycle cops. The area is approachable by only four roads one from Mexico, one from Arizona, one from San Diego, and one from San Bernardino. The workers are bottled up and patrols keep a rigid watch to prevent any food supplies from being shipped in to them.

A telegram from Brawley reads: “Strikers ready to starve fighting but must have funds for gas.” The workers are at the expense of about $65 a day for gasoline to transport strikers to and from picket lines in over a hundred cars.

On Jan. 9, several hundred workers held a meeting in the public square of Holtville. They voted to march to El Centro in a demonstration. Police and legionnaires attacked them with tear gas and a battle ensued in which bombs were caught in bare hands and hurled back at the deputies.

The headquarters of the C. & A.W.I.U. in Azteca Hall at Brawley has been raided three times, resulting in three pitched battles between the workers and the police and legionnaires. These raids took place on the tenth, eleventh and twelfth of January. The hall was demolished, typewriters smashed, and the building flooded by the fire department. One hundred and fifty arrests were made in the first raids and 350 in the last. All these workers have been held for serious charges. Their only offense has been to ask for a living wage. Tear gas was used in these instances and has been used in numberless smaller clashes in which arrests have been made all over Imperial Valley.

As I write this, a report has come that hundreds of automobiles have been either wrecked or confiscated by the police and legionnaires.

A large percentage of the lettuce pickers are migratory workers who follow the crops. Many of them faced the same struggle in the San Joaquin Valley last year. The majority of them are Mexicans, hundreds of whom have been rounded up for deportation. There is a queer contradiction in this. Growers of Imperial Valley and the Southwest have registered protests in Washington to the effect that if Mexican workers are excluded from the country, their lands will go back to the desert. The entire agricultural development of the Southwest has been accomplished by Mexican labor. The Mexican workers did not force their way into the United States. They were solicited and brought in by American industrialists. During the War they were absorbed into the heavy industries of the North along with the Negroes. Southwestern agriculture is as dependent upon Mexican labor today as it was the day it began. The Mexican worker’s own country has been bought from under his feet by foreign capital. A situation exists in Mexico today which has the same potentialities that led to the Cuban revolution. The Mexican worker knows that the border line is a mockery (like the mockery of Cuban independence) and whether he is in the United States or in Mexico his struggle against starvation is a struggle against American capital. He has poured the best of his strength into American industry; deserts converted into blooming farm lands, bridges, dams and thousands of miles of railroad are monuments to his energy. His case is as just and his rights as valid as the American and Negro workers with whom he has joined hands in struggle.

As in all other States, the Roosevelt recovery program is administered in California with blackjacks, tear gas, guns and fire hose. Wherever the workers face the government they face squads of police, vigilantes and legionnaires ready to slug or to kill in the interests of the private industrial owners. Anything that can possibly be construed as in the interests of the workers is immediately labeled “RED,” and with some justice. Certainly the only support and aid that the workers have received in their struggles has come from the Communist Party and its subsidiary organizations, and through them from the workers in all other industries and from the sympathetic elements among the bourgeoisie. The government offers tear gas. The reformers offer verbal sympathy. The Communist Party joins their struggle, rallies support, def ends their class war prisoners and is not merely for them but of them.

The New Masses was the continuation of Workers Monthly which began publishing in 1924 as a merger of the ‘Liberator’, the Trade Union Educational League magazine ‘Labor Herald’, and Friends of Soviet Russia’s monthly ‘Soviet Russia Pictorial’ as an explicitly Communist Party publication, but drawing in a wide range of contributors and sympathizers. In 1927 Workers Monthly ceased and The New Masses began. A major left cultural magazine of the late 1920s and early 1940s, the early editors of The New Masses included Hugo Gellert, John F. Sloan, Max Eastman, Mike Gold, and Joseph Freeman. Writers included William Carlos Williams, Theodore Dreiser, John Dos Passos, Upton Sinclair, Richard Wright, Ralph Ellison, Dorothy Parker, Dorothy Day, John Breecher, Langston Hughes, Eugene O’Neill, Rex Stout and Ernest Hemingway. Artists included Hugo Gellert, Stuart Davis, Boardman Robinson, Wanda Gag, William Gropper and Otto Soglow. Over time, the New Masses became narrower politically and the articles more commentary than comment. However, particularly in it first years, New Masses was the epitome of the era’s finest revolutionary cultural and artistic traditions.

PDF of full issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/usa/pubs/new-masses/1934/v10n04-jan-23-1934-NM.pdf