An essay by David Ivon Jones on the history of Lenin’s ‘Isrka’ project.

‘’Iskra,’ the Spark that Grew Into a Flame’ by David Ivon Jones from the Daily Worker (Saturday Supplement). Vol. 2 No. 98. July 12, 1924.

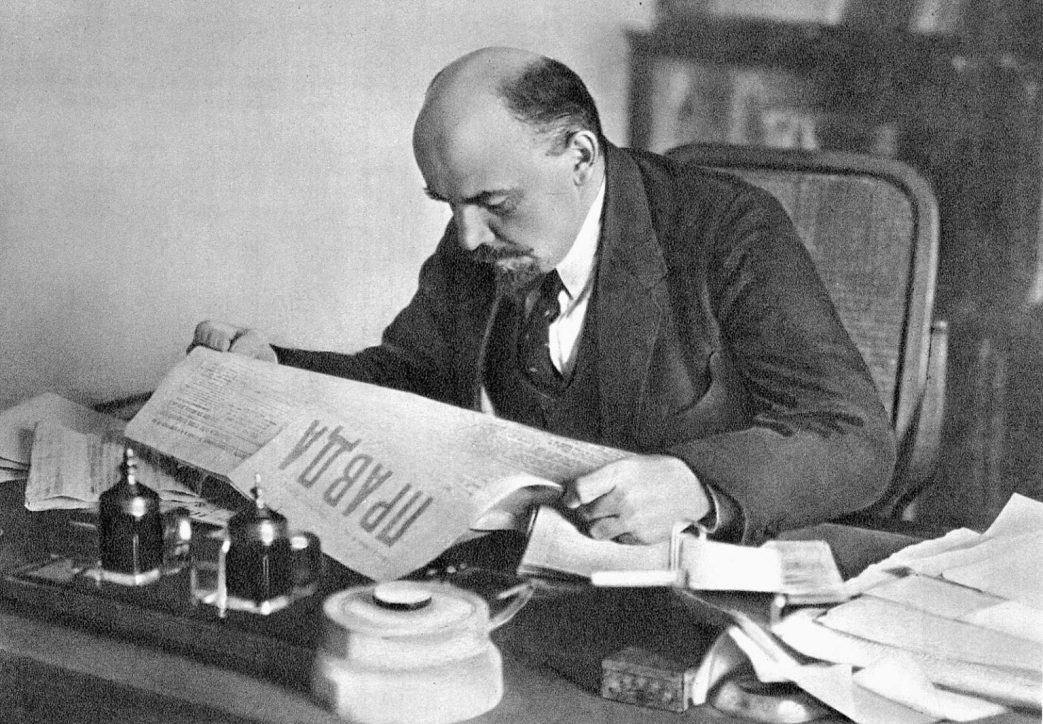

LENIN’S newspaper, Iskra, (“The Spark”) formed the starting point for the formation of an organised party of the proletariat in Russia, when the words Menshevik and Bolshevik had not yet been coined. In order to understand the character and purpose of the journal, it is necessary to go back a few years.

When Lenin appeared in Petrograd in 1894, and began to form Social-Democratic groups of workers and intellectuals, the Social-Democratic idea,* which then synonymous with revolutionary Marxism, had always been disseminated in Russia for about ten years, but only among isolated individuals here and there. A number of Russian Marxists, prominent among whom were Plekhanov and Axelrod, had formed the “group for the emancipation of Labour,” in Switzerland. They worked, as it were, in the absence of a workers’ movement, when it was still a question of theory, as far as Russia was concerned. They perforce confined themselves to the literary task of popularising the Marxian principles among the Russian revolutionaries, who were in a state of disillusionment and disappointment at the failure of the “Narodvoltzi” (Populist) creed, which based its hopes upon the peasant.

Lenin started the period of action in Russian Social- Democracy. But, as we saw in our previous article, the also, most effectively of all, incarnated Marxism in the flesh of actual Russian economic conditions. This he did in his controversy with the “narodniki.” He left a monument to this controversy in his masterly work, “The Development of Capitalism in Russia.”

But Lenin not only wrote. With him theory served to give replies to the problems arising out of the struggle. He formed groups of workers to organise agitation in the various workshops of Petrograd. The agitation among the workers took the form of issuing leaflets in connection with a certain factory, flagellating the abuses and oppressions, the petty fines, etc., to which the workers were subjected. But Lenin’s group not only advanced particular economic demands, but also the struggle for the overthrow of Czarism, thus placing the workers in the forefront of the struggle for political freedom. And the workers readily responded. A wave of strikes dated from this time. The workers finally demonstrated their capacity for political struggle, which was of vast importance in winning over the revolutionary intelligentsia to Marxism.

Needless to say, the agitation had to be carried on under the severest conspirative conditions. The growing working class revolt roused the forces of the Czarist police to action, and, at the end of 1895, practically the whole of Lenin’s group, the Group for the emancipation of the working class,” was arrested, including Lenin himself. In 1897, Lenin was exiled to Siberia. There, however, he managed to continue his literary work, his controversy with the legal “narodniki,” besides writing on the urgent tasks of the Social-Democrats in Russia in the light of the experience gained in the first attempts in Petrograd.

While Lenin was in exile, Social-Democratic groups were being formed in all the large cities of Russia, and an attempt was made to hold the first congress at Minsk, in 1898. But, as Lenin afterwards showed, the young Social Democrats, were as yet inexperienced in conspirative organisation, and the central organisations set up by the Congress were broken up by the police as soon as formed. Nothing remained but the Manifesto of the Congress. So that there was still no organised Party. It remained an idea, a trend. There was no co-ordination among the groups. Each was a law to itself and each had a different interpretation of the Social-Democratic programme, tactics and methods of struggle. This was the period of the groups or circles.

Lenin returned from exile in 1900. In the five years since his arrest, the elemental uprising of the workers had taken a mass character. This disquieted Lenin, even while it filled him with confidence in the working class, as all elemental uprisings without conscious direction disquieted him. He saw the mass movement going ahead of the conscious Social-Democratic movement, and he sounded the alarm. He saw much that was contrary to Marxism in the tactics and teachings of the young groups. A certain vulgarisation of Marxism, a kind of “I.W.W.ism,” had taken hold among the revolutionary youth during these five years.

This trend was known as “economism.” The “economists” declared the economic struggle to be paramount. “Politics follow economics,” they said. “Leave politics to the liberal bourgeoisie; and all this talk about the overthrow of Czarism is not the concern of the workers. Talk to the workers about matters that promise palpable results. Too much ideology, too much theory, etc., etc.” How familiar all this is to any Party worker no matter in what part of the world he may be! Lenin sensed a great danger in this trend. With the air of being ultra-working class, the economists reduced working class politics into a tool of the bourgeoisie. For many at that time wanted the revolution who were not of the working class movement, but saw in the working class a force to be exploited politically. The liberal bourgeoisie desired revolution of a sort. The petty bourgeoisie desired revolution. Whose revolution it was going to be, whether the proletariat should be a tool in the service of the bourgeoisie, or whether it should retain the lead in the revolution, depended on the correct proletarian tactics and the correct methods of organisation in these critical days. The revolutionary intelligentsia were prone to say: “The proletariat is necessary for the revolution.” Plekhanov corrected them from his Geneva study: “No, on the contrary, the revolution is necessary for the proletariat.” Such were the “economists,” consciously or unconsciously reducing the role of the proletariat to an appendage of the liberal bourgeoisie.

Lenin now saw himself obliged to carry forward the theoretical struggle from the domain of programme (controversy with the narodniki) to the domain of tactics and methods of organisation, namely, the fight with the “economists” within the Social- Democratic movement. On his return from exile Lenin, and a few others who held similar views, met at Pskov to consider the needs of the movement. It was decided to start an all-Russian Social-Democratic newspaper. There had been several previous attempts made to start a paper. Some had had a short-lived existence before being discovered and suppressed; others, like the “Rabochi Dyelo (“Workers’ Cause”), the first paper printed by Lenin’s group in 1895, had been seized by the police before leaving the press. The only hope of success was to establish what Lenin called a base of operations beyond the reach of the Czarist police, that is, abroad, and thereto establish a news- paper which would be an ideological guide for the movement, gathering the various groups together round the true Marxist tactics and methods of organisation. For this purpose, Lenin was selected to go abroad and establish contact with the Plekhanov group, enlisting their aid in the work.

In this task Lenin had brilliant success. He established the now famous newspaper, “Iskra,” (The Spark), and the “Iskra” organisation for the dissemination of the paper. The paper became not only a theoretical guide, but an organisational centre, to which group after group adhered, to form the basis for an All-Russian Party of the proletariat.

But, needless to say, “Iskra” met with considerable opposition from the economists within the movement. For, was it not formed to wage uncompromising war on Economism, which exalted the immaturity of the movement into a considered policy? In its first announcement, the paper declared: “Before we unite, and in order that we unite, it is necessary first of all resolutely and definitely to divide.” Here, however, there was no question of splitting any organisation, for a centrally organised party did not yet exist. It was “Iskra’s” task to form it. But, first of all, it was necessary to delimit, fix boundaries, define the Social- Democratic method and those who belonged to it, and label those who departed from it; separating the tares from the wheat. And the tares at this time were the “economists.”

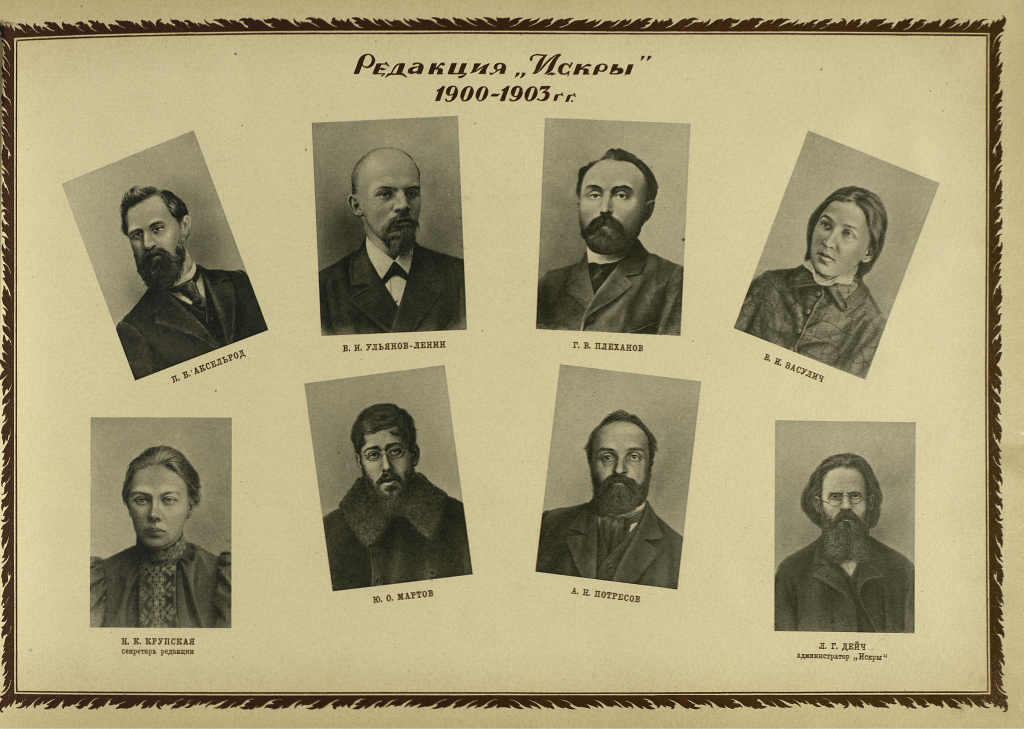

Plekhanov, Martov, Axelrod and others were on the “Iskra” editorial committee. But “Iskra” was essentially Lenin’s paper. “Of all these, Lenin alone had clear, impelling ideas as to what the movement needed. He put forward the celebrated idea of an organisation of professional revolutionaries.” He had seen group after group broken up by the police, every forward movement thwarted by wholesale arrests because of what Lenin called a “tinkering” view of the incredibly difficult task of counter-acting the political police. A broken up group, having no link with a central organisation, left no trace whereby its activities could be speedily revived. Lenin demanded a centrally directed organisation of comrades as scientifically equipped as the police in the art of conspiracy— “professional revolutionaries” the ironsides of an All-Russian Party, of the Proletariat. “Iskra” also elaborated in detail the plan of such a Party, and not only proposed this, but proceeded to carry its ideas into practice, gathering round itself group after group of adherents in the various industrial centres of Russia.

In 1902, a year after starting “Iskra,” Lenin issued his epoch-making brochure, entitled, “What Must We Do?” This he describes as a synopsis of the “Iskra” tactics and methods of organisation. The book became a veritable storm centre in Russian Social Democracy, not only because of its campaign against economism,” but also because it laid down principles of Party organisation which went much further than the fight against economism. “What Must We Do?” cleared economism off the field, but it raised new issues, a new conflict on a higher plane, which a year later crystallized in the division of the movement into Menshevism and Bolshevism.

Meanwhile “economism,” degrading the political role of the proletariat, found its kindred expression in Bernstein’s revisionism. At first glance the latter had little in common with the slogans of economism.” But Lenin branded it as the Russian form of opportunism. The “economists” chafed at the rigours of “orthodox” Marxism, and demanded, like their German confrere, “freedom of criticism.” This brought from Lenin a retort characteristic of the uncompromising revolutionary: “People who are really convinced that they carry science a step forward would demand, not equal freedom for the new theory along with the old one, but the substitution of the old by the new,” and, in the first chapter of “What Must We Do?” he adds: “Oh, yes, messieurs, you are free to invite, and, not only to invite, but to go where you please, even to the morass; we even think that the bog is your proper place, and we are prepared to lend you every support for your migration thereto.” Lenin believed in giving the confirmed opportunist a push to the right!

At this time, using the terminology of the French revolution, “Iskra” declared the existence of the Mountain and the Gironde in the Russian proletarian movement. Indeed, Plekhanov, some time before Lenin’s arrival in the “emigration,” had broken with the “Union for the Emancipation of Labour,” because of its “economism” and had formed the “League of Social Democrats.” But Lenin does not seem to have suspected (or else deemed it unwise to reveal his suspicions), that the final cleavage should take place on a line between him and his “Iskra” colleagues, Plekhanov, Martov, Axelrod, and other But this amazing “right- about-face” to opportunism, constituting one of the most striking studies in the psychology of menshevism, must form the subject of a separate article, devoted to the Menshevik split.

“What Must We Do?” in spite of the familiarizing of Leninism by the Communist International, has till much that is new and startling to the English reader, and it is to be hoped that these early Lenin brochures will soon be published in the English language. It is inevitable that we should become more and more familiar with their historical allusions, as allusions to our classic history. For Lenin was wont to say, “It is an axiom of the Marxian dialectic that there is no abstract truth, truth is always concrete.” And one may say that what the “Communist Manifesto?” is to Marxism in its first phase, so is “What Must We Do?” to Marxism in its second phase, the phase of action, in its Leninist phase. Take the second chapter of this brochure, entitled “The Elemental and the Conscious.” Opportunism, at first taking the form in Russia of “economism,” magnified the role of the elemental or the spontaneous in the workers’ mass movement. The “economists” accused “Iskra” of exaggerating the “factor of consciousness (vide Engels’ definition of the Party as “the conscious expression of an unconscious process.”) The “economists” opposed what they termed their “tactic-process” to the “Iskra’s tactic-plan.” Lenin was filled with profound uneasiness at every spontaneous uprising of the workers in the absence of mature party guidance. The backwardness of the Party disquieted him. He invented a special nickname for the economists’ tactic—” hang-on-the-tailism,” which is used to-day in the Russian movement. He accused the “economists” by their genuflections before the “elemental” of wanting the party to be forever “studying the hindquarters of the proletariat,” of making the principle of the class struggle an excuse for waiting on events, instead of forestalling them, dominating them. exaggeration of the elemental, and depreciation of the conscious, factor in the Labour movement is a strengthening of bourgeois influences among the workers.” He denied the current impression that Socialist consciousness comes to the workers inevitably from their conflicts with individual capitalists. “The workers by their own strength can only achieve Trade Unionist political action.” “The spontaneous workers’ movement of its own accord is capable only of forming (and it inevitably forms) trade unionism; and trade unionist political action of the working class is precisely bourgeois political action.” Lenin roundly accuses the economists” of an “oblique attempt to prepare the ground for transforming the workers’ movement into a tool of bourgeois democracy.” Further on Lenin devotes several pages to “Trade Unionist versus Social Democratic political action,” with copious references to English Trade Unionism. Reading these chapters, one receives a flash of revelation as to why great waves of working class mass action have swept over England and receded again, leaving hardly a trace in the collective experience. For this collective experience can only be garnered by a Communist Party. This responsibility of the individual before history, the role of human initiative of the Party, is the great Leninist corrective to the conception of Marxism hitherto prevailing in the West. If the “great man theory” be regarded as the thesis, and historical materialism (vulgarised) as the antithesis, then Leninism, the restoration of the emphasis on conscious initiative, is the synthesis of it all. In “What Must We Do?” we feel this power, this revolutionary driving force, permeating every phrase. He conceives the role of the revolutionary as the liquidator of outworn historical periods, the refuse of which encumbers the way. He concludes the preface to this book with the words, “For we cannot move forward unless we finally liquidate this period (the period of the groups).”

Lenin’s chief antagonist among the “economists” was Martuinov (not to be confused with Martov). Now Martuinov is in his own person a living symbol of Lenin’s driving power on history. Martuinov started his career with the “narodniki” (the Populists) and left the “narodniki” when their position became untenable from the attacks of Plekhanov and Lenin. He then became an exponent of “economism” economism” in the Social- Democratic movement. Economism in its turn was smashed under Lenin’s sledge-hammer blows, and Martuinov had to move forward to a more consistent position. Later, he took the Menshevik side in the great division, and even became its official theoretician. Last year, after twenty years, Martuinov unconditionally capitulated to his old opponent and signalized the complete downfall of Menshevism by going over to the Communist International. “Thou hast conquered, oh, Galilean!”

Before leaving the subject of “Elemental versus Conscious Action,” let us indulge ourselves in one more quotation: “ Only the most vulgar understanding of Marxism, or the ‘understanding’ of it in the spirit of Strouvism,* could engender the idea that the upsurging of the spontaneous mass movement of the workers relieves us of the duty of forming such an efficient organisation as that of the zemlevolio,* nay, of forming an incomparably more efficient organisation of revolutionaries. On the contrary, this mass movement precisely imposes upon us this duty; for the spontaneous struggle of the proletariat does not become a real class struggle until it is directed by a strong organisation of revolutionaries.”

“What Must We Do?” devotes much space to the question of party democracy; and the recent discussion in the Russian Communist Party can only be fully comprehended in the light of these early works of Lenin. In the days of “Iskra” it was a question of party democracy in a severely conspirative organisation, but the Leninist axioms retain their force. “A revolutionary organisation,” he says, “never could and never can, with the best of intentions, install the broad democratic principle.” Primitive democratic notions, such as the one that a people’s newspaper should be edited directly by the people, were rife among the revolutionary youth, as a revulsion from absolutism. Lenin had to fight against these primitive notions in order to establish his organisation of “ironsides.” “The broad democratic principle is impossible without full publicity.” Lenin was a sworn enemy of the principle expressed in the words “from the bottom up.” He demanded that the Party be organised from the top down. Not on democracy, but on the mutual faith of comrades. Vulgar democratic tendencies in the Party reflect bourgeois democratic party tendencies.”

Lenin published a reprint of “What Must We Do?” in 1907, during the temporary spell of political freedom under the Duma. In the preface to that edition, he refers to the organisation of professional revolutionaries as having well completed its work and planted the party on impregnable foundations. In the same connection, he welcomes the introduction of the elective principle in the party organisation owing to the greater freedom of action. But that freedom was short-lived. The party had to return underground. And it is only now that the Party, emerging from the period of civil war, has been able to apply workers’ democracy to the Party apparatus. Nevertheless, Comrade Kamenev warned the Party against “vulgar democracy,” which is only bourgeois democracy, excluded from all other avenues, knocking at the door of the Party.

Who said that Lenin had no humour? His was a versatile, many-sided genius. What Must We Do?” like all his brochures, teems with humourous asides, a certain pawky Scotch humour which keeps close to the gist of the matter. He refers for example to Soubatov, the Czarist agent, who was known to be in favour of legalising trade unions, and who instigated strikes, Lenin said in effect, “All right, we’ll gain from it in spite of the tares in the wheat, we don’t want to grow wheat in flower pots.”

The spirit that animated Lenin was a pride in the working class, unbounded faith in the proletariat. He denounced any and every attempt to degrade its political role. “The consciousness of the working class cannot be a truly political one unless the workers respond to every case of oppression, violence and abuse, no matter to what class they are applied.” (p. 78). When the Czar’s government drafted 183 students of Kiev University into the army, in punishment for insubordination, “Iskra.” called for workers’ demonstrations of protest. And the workers responded, a fact which Lenin exultantly shows to the economists.

This exalted view of the role of the proletariat is balanced by a sense of tremendous responsibility.

“Our backwardness,” he says, “will be inevitably taken advantage of by more agile, more energetic ‘revolutionaries’ outside Social Democracy; and the workers, no matter how boldly, and energetically they may fight the police and the soldiers, no matter how revolutionarily they may act, will be only a force in support of these ‘revolutionaries’; they will be just the rear-guard of bourgeois democracy, instead of being the Social-Democratic [read Communist] advance guard.”

He hurls the word “tinkers” again at the “economist defenders of party backwardness. And then, all at once, we have another Lenin, the master, unsparing above all towards himself.

“Don’t be aggrieved with me for this harsh word,” he says. “For, in so far as it is a question of unpreparedness, I apply it to myself. I worked in a group which set before itself a very broad, all-embracing task, and to all of us members of that group came the torturing feeling that we were nothing but tinkers, at an historic moment when it was possible to say, adapting a well-known phrase: ‘Give us an organisation of revolutionaries, and we will conquer Russia.’ And, since then, the more I recall that bitter feeling of shame, which I then experienced, the more does my choler rise against those false Social-Democrats who, by their preachings, debase the revolutionary name; against those who do not understand that our task is not to condone the debasement of a revolutionist into a tinker, but to raise the tinker to be a revolutionist.”

These lines were written many years before the October revolution, but, in reading “What Must We Do?” one feels that the critical days of the October revolution were not the days of October. It would have been too late in 1917 to form that ironclad Party-steeled in two revolutions, and in innumerable contests with the Czar’s police-capable of leading the proletariat along the inconceivably difficult paths of the proletarian dictatorship. And this titanic struggle of the Russian proletariat, a struggle which has also cleared the path of the Western revolution, was only possible as the fruits of an equally titanic theoretical struggle waged by Lenin in the first years of the century. And Lenin, in “What Must We Do?” pierces into this future, as. is his wont. Marvelous prophet—in the power of his revolutionary logic the future blends with the present in one iron inevitability. He has just been quoting Engels on the leading role of the German proletariat in the international movement, and says:

“Before the Russian workers now stand immeasurably heavier trials, now stands a struggle with monsters, compared with which the exceptional laws in a constitutional country are a mere bagatelle. History has placed before us the immediate task, which is the most revolutionary of all the immediate tasks of the proletariat of any country. The realisation of this. task, the destruction of the most powerful buttress, not only of European, but also (we may now say) of Asiatic reaction, would make the Russian proletariat the advance guard of the international revolutionary proletariat. And we have a right to expect that we shall achieve this honourable role, already earned by our predecessors of the seventies, if we can inspire our movement which is a thousand times deeper and wider than theirs, with the same unsparing devotion and energy.”

And so it came to pass. Whatever Lenin set himself to do he achieved. And his deathless name shall still lead us on from strength to strength; and revolution after revolution shall be monuments to his memory.

* The word “Social-Democratic is retained throughout the present article because it then stood for revolutionary Communism, and was so used by Lenin.

* See reference to Strouve in previous article (March) on Lenin’s First Book.”

* Zemlevolio (Land and Freedom) preceded the “narodvoltzi” (Peoples Freedom Party) in the revolutionary seventies.

The Saturday Supplement, later changed to a Sunday Supplement, of the Daily Worker was a place for longer articles with debate, international focus, literature, and documents presented. The Daily Worker began in 1924 and was published in New York City by the Communist Party US and its predecessor organizations. Among the most long-lasting and important left publications in US history, it had a circulation of 35,000 at its peak. The Daily Worker came from The Ohio Socialist, published by the Left Wing-dominated Socialist Party of Ohio in Cleveland from 1917 to November 1919, when it became became The Toiler, paper of the Communist Labor Party. In December 1921 the above-ground Workers Party of America merged the Toiler with the paper Workers Council to found The Worker, which became The Daily Worker beginning January 13, 1924.

PDF of full issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/usa/pubs/dailyworker/1924/v02a-n098-supplement-jul-12-1924-DW-LOC.pdf