‘The Proletarian Film in America’ by William F. Kruse from International Press Correspondence. Vol. 6 No. 12. February 11, 1926.

The motion picture film is the most potent means of moulding mass opinion to be found in America. Every week more than 50,000,000 people visit the 20,000 regular movie theatres, to say nothing of the attendance in the 100,000 clubs, schools, church halls and other places equipped for showing films. The importance laid by the capitalist class on this means of propaganda is shown on the one hand by the strict censorship regulations, and on the other by the extreme skill with which master class ideology is woven into almost every product of the film trust. Organisational steps are taken to insinuate the film everywhere — for the children there are school showings and special Saturday morning shows in theatres, for the backwoods rural public there are State-operated travelling outfits that show in country school houses or even in open air, — the films are brought, at capitalist expense, into factories, clubs, churches and even into the prisons. The propaganda potency of the film in America outweighs the combined influence of newspapers, public libraries and lecture platforms.

Our movement has been forced to try to meet this new weapon of the master class, to try to turn it to its own service. To some measure we have met with success, as have also the comrades in other countries, but the further development of this work must be organised on a world-wide scale with the film industry of Soviet Russia as a basis. The terrific propaganda force of the bourgeois “Film News Weeklies” must be countered with a “Workers’ Film News Weekly” to give the latest happenings in the world of labour, and especially in Soviet Russia.

The subtle “tendency” films of the capitalists must be countered with those giving the working class ideology. The film in church and school must be countered with those giving the working class ideology. The film in church and school must be countered with the worker’s film in the Labour Temple.

In the United States we were compelled to the use of motion pictures by the actual needs of our campaign for Russian relief in 1921. The American workers at that time were in a generally progressive trend, their sympathies were instinctively with Soviet Russia, but we had to find some means of bridging the gap that separated us from these essentially friendly but inaccessible masses. Our meetings were small and attended mainly by ourselves and our closest sympathisers. The first step, that of lectures illustrated by lantern slides, was soon followed by the second — the motion picture film.

Its success from the very first, was tremendous. The largest theatres in the industrial centres could not hold our crowds, and even where our membership was infinitesimal, even in the smallest hamlets. the message of Soviet Russia was presented with the same uniform perfection to crowds that never before paid the slightest attention to our meetings, newspapers or literature. The first picture was also a distinct financial success, its gross receipts coming to $40,000. Of course as the novelty of workers’ film wore off, as in conformity with the general proletarian trend of that time the wave of revolutionary and humanitarian interest in Russia subsided among the American workers, the financial returns became progressively less, but actual financial less has always been avoided. The financial gains are entirely dwarfed, however, by the tremendous propaganda value of this new medium, each of our five full film programmes has thus far played in 200 cities (in many of which we had no organisation whatever) and before 100,000 to 150,600 people and in addition our films deserve chief credit for the success of many meetings and demonstrations. The newspaper publicity attending the showings, the broad campaigns resulting from numerous cases of attempted suppression must be added to the direct propaganda results. There should be added also the subjective benefit to our movement, just then cautiously emerging into legality: the big halls, theatres, public buildings, that were requisite, the relatively enormous amount of advertising necessary, the whole compulsory mass approach that the film brought with it was of inestimable value in encouraging and strengthening the young movement.

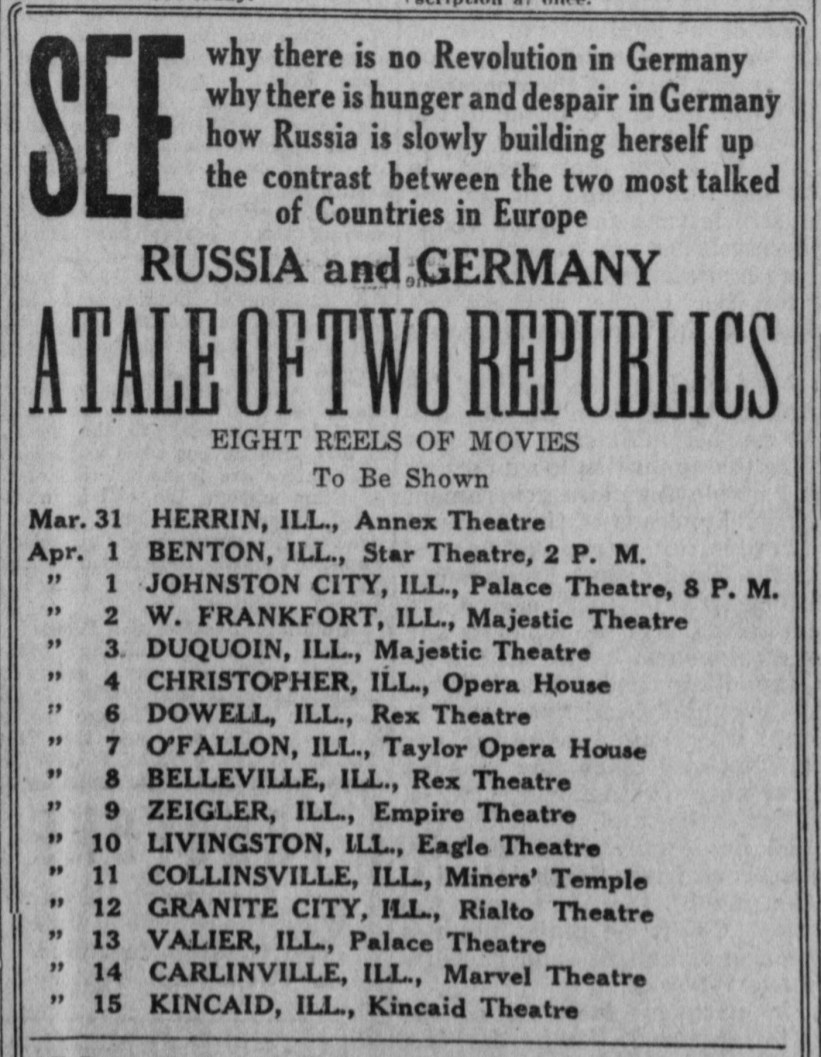

Our first picture. “Russia Through the Shadows”, was made up from a fortuitous purchase of some 1917 revolutionary film, and famine scenes from the Workers’ International Relief, padded out with our own photography of our various relief activities in America and on, our Ural tractor farm. Technically it was infantile, but its interest tremendous. “The Fifth Year”, was made up out of about 40 Russian newsreels, including May Day demonstrations, S. R. trial, army manouevers, sport, industrial reconstruction and the overcoming of the after-effects of famine. Technically it was excellent, colour-photography and animated trick film being employed to dress it up on American technical standards. The propaganda possibilities of trick film — if technically well made — are unlimited. Then followed, among actual subjects, “Russia and Germany”, contrasting the effects of revolutionary and reformist labour politics; “Russia in Overalls” showing industrial revival; “Russia Today”, the social and industrial life of Russian asbestos miners; “Lenin”, scenes from old films added to the funeral pictures; and finally, “Prisoners for Progress”, a Mopr (International Class War Prisoners’ Aid) film of direct propaganda nature. Of story films we had three, “Polikushka”, “Soldier Ivan’s Miracle”, and “Kombrig Ivanov”. We have supplied films to the Canadian movement, and negotiations are now under way to do the same for Mexico and Argentine.

In addition to these chiefly Russian subjects we produced several American labour news-reels on such subjects as the Paterson silk strike, the police brutality in the Chicago stockyards strike, the Herrin battle, meetings of unemployed returned soldiers, Labour Party conventions, Lanzutsky demonstrations before the Polish consulates, our Presidential candidates; most of these we photographed ourselves, a few we bought at very low prices. We now have a sufficient amount of material on war, imperialism, and American labour conditions to make an interesting American labour film but we lack the means to finish it off. These news-reels were issued in the form of “Film Editions of the Daily Worker”, thus giving our organ greater publicity among the working masses as well as the honour of being the first Communist Daily to bring out its stories on celluloid.

This work has of course met with stiff opposition from the capitalist state. In about 8 states (of 48) and about 50 cities there are censorship provisions to be met, but thus far we have very seldom failed. Often it was necessary to roll up a mass protest movement to force the censors to withdraw hostile rulings. in such campaigns trade unions (0n two cases State Federations of Labour) and many liberal organisations were enlisted, and appeals made to the highest instances. Wherever a film is temporarily banned it results in added success when it is finally shown. There were also a few cases of police closure of halls, and arrest of our committees, and some rare instances of extra-legal violence of Fascist type, as well as occasional projectionist sabotage. Opposition generally resulted in greater publicity gains than the loss it entailed.

The showings were mostly held in rented theatres, though in many cases schools and other public buildings were secured through liberal or labour aid. In small towns theatre owners dependent upon labour support rented our pictures as part of their regular programme, often, too, Labour Temples were used. An itinerant projection outfit is now being planned to work in the rural and small isolated mining districts, and consideration is being given to equipment that permits pictures to be shown in daylight.

Our work has now reached a temporary impasse for lack of new film material. Many of our locals demand new pictures lor this season and it is expected to meet it by the Mezhrabpom film “Lenin’s Call”. Unfortunately the season will be practically over before it can be made available, thus a whole Winter has passed minus film propaganda and revenue. The experiences of the American movement, as well as those of other countries where film has been employed with greater or less success. should lay the basis for a proletarian film service and exchange that is truly international in scope.

The Soviet Union must of course be the economic and ideological foundation for this work. By means of the film the truth about Communist Russia can be shown before the very eves of the Western workers — we can show them the revolutionary past and present, as well as the news of our everyday upbuilding of Socialist society. Only a very few can come on the various Workers’ Delegations and see for themselves with their own eyes, but by taking motion pictures of what these delegations see and do in Russia we can bring before the eyes of the masses the same sights that greeted and convinced their delegates.

International Press Correspondence, widely known as”Inprecorr” was published by the Executive Committee of the Communist International (ECCI) regularly in German and English, occasionally in many other languages, beginning in 1921 and lasting in English until 1938. Inprecorr’s role was to supply translated articles to the English-speaking press of the International from the Comintern’s different sections, as well as news and statements from the ECCI. Many ‘Daily Worker’ and ‘Communist’ articles originated in Inprecorr, and it also published articles by American comrades for use in other countries. It was published at least weekly, and often thrice weekly. The ECCI also published the magazine ‘Communist International’ edited by Zinoviev and Karl Radek from 1919 until 1926 monthly in German, French, Russian, and English. Unlike, Inprecorr, CI contained long-form articles by the leading figures of the International as well as proceedings, statements, and notices of the Comintern. No complete run of Communist International is available in English. Both were largely published outside of Soviet territory, with Communist International printed in London, to facilitate distribution and both were major contributors to the Communist press in the U.S. Communist International and Inprecorr are an invaluable English-language source on the history of the Communist International and its sections.

PDF of full issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/international/comintern/inprecor/1926/v06n12-feb-11-1926-Inprecor.pdf