When and why the Pennsylvania State Police were formed. A fine article from Alexander Berkman on the uprising of the ‘hunkies’ in the 1909 McKees Rocks Pressed Steel strike outside of Pittsburgh; one of the most consequential, and violent, strikes in U.S. history.

‘The Pennsylvania Constabulary and the McKees Rocks Strike’ by Alexander Berkman from Mother Earth. Vol. 4 No. 7. September, 1909.

EVEN before the memorable days of the Homestead strike, of 1892, there was a law on the statute books of Pennsylvania forbidding the importation of armed men from other States. Heavy penalties were attached to the offence.

However, when the Carnegie Steel Company was preparing to destroy the Association of Amalgamated Iron, Steel and Tin Workers, the then Chairman of the Company, H. C. Frick, imported armed Pinkertons from Chicago and New York to intimidate and shoot down the locked-out men. The history of that. great struggle is well known. But when the strike was finally settled, public sentiment forced the District Attorney of Allegheny County to bring charges of murder against Frick and other officials of the Carnegie Company, they being legally responsible for the atrocious deeds of their imported myrmidons.

Naturally, the authorities felt too much respect for the Carnegie-Frick millions to press the charge of murder. It was feared that a jury of citizens might possibly send the Carnegie officials to prison. The cases were therefore never permitted to come to trial. But the popular outcry against the importation of armed ruffians became so strong that the Pennsylvania legislature was forced to action. The already existing statute was amended, making the importation of armed men treason against the State, punishable with death.

The industrial Tsars of Pennsylvania were not at all pleased with the situation. The new law expressly forbade the employment of Pinkertons, foreign or local. The people execrated their very name. It would be risky to face a charge of treason. The local Iron & Coal Police were not sufficient to “deal effectively” with great strikes; nor was it financially advisable to keep a large private standing army who would have to be paid even when there were no strikers to be shot.

The coke, coal, and steel interests of Pennsylvania (practically the same concern) faced a difficult problem. They were preparing to wage a bitter war against organized labor, fully determined to annihilate the last vestiges of unionism among their employees. It was to be done effectively, yet economically. A very difficult problem. At last the solution was found. A high-priced steel lawyer struck the right key. It was quite simple. Why risk popular wrath, possible prosecution for treason and murder, by employing Pinkertons? Why even go to the expense of hiring an army of private guards? It would be far cheaper and safer to have the great State of Pennsylvania act as their Pinkerton. What is the State for if not to protect the lords of money and subdue grumbling labor? The good taxpayers will do the paying.

A bill was introduced in the legislature. Just a little bill; On its face it looked quite harmless. Some burglaries had been committed in the outlying western counties; the local police, it was said, could not cover the extensive territory; the smaller towns and villages were too poor to increase their police forces. The State should protect the weak. Let it therefore organize a special force to take care of the more obscure districts. Only that. Their sole duty would be to patrol the unprotected places.

The astute steel and coal lawyer knew how to make the proposed law look inoffensive. It passed without opposition.

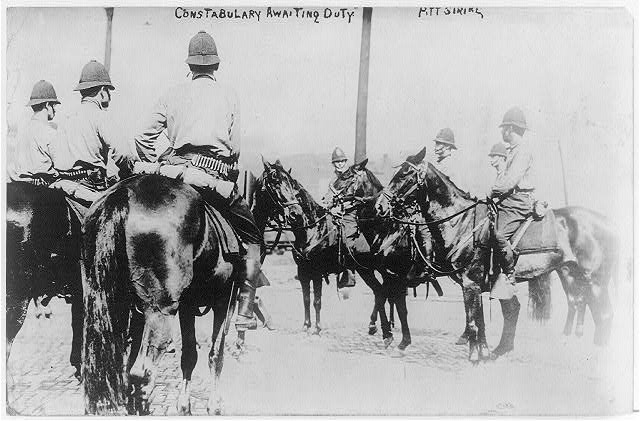

No time was lost in the organization of the newly created State police, called constabulary. But the hasty passage of the law, the unusually large appropriation made for the purpose of organizing a “small patrolling body,” the almost dictatorial powers vested in its commander, and the latter’s militant attitude from the very beginning, soon began to arouse misgivings on the part of organized labor. But their fears were quickly allayed with the assurance “from authoritative sources” that “honest workingmen had nothing to fear” from the constabulary. These were merely to patrol the outlying, unprotected districts; they would not mix in local affairs; they had nothing to do with strikes; they’d be good.

The average man has great trust in the word of authority. The workingman especially is trained—at home, in school, shop, and union—to respect the powers that be. Therefore, when the Governor of the great State of Pennsylvania personally assured some protesting labor men that “honest workingmen had nothing to fear from the constabulary,” it was considered complete proof that all was well.

Then the constabulary got into action. It was recruited from the most brutal and savage social elements. Proven recklessness of human life was an indispensable qualification. The reputation of having “killed his man” was the standard of admission. It was the widely-heralded ambition of the constabulary’s commander to make his force a “terror to evildoers.” He openly boasted the motto, “Shoot to kill.” The pay of his men was generous.

It was not long before the real mission of the State troopers became evident. They made no attempt to do mere patrol duty. Instead, the least sign of dissatisfaction among men employed on the highways, track-layers, miners, and coke workers would immediately result in a descent of troopers. They terrorized the foreign workingmen, clubbing and shooting indiscriminately, and even invading peaceful homes in the dead of night to search for alleged weapons and to drag their unfortunate victims to prison, forcing them to run over miles of rough country chained to the saddles of the galloping horses.

The name “trooper” soon grew to be a terror, indeed. They quickly earned the reputation they aspired to, proving themselves more inhumane and cruel than Russian Cossacks.

It gradually became the established custom to employ the constabulary in strikes. Clothed with full power over life and death, absolutely arbitrary and irresponsible, they have terrorized the whole of Western Pennsylvania, participating in every strike since their organization. The brutality with which they have helped the traction company of New Castle to break the street car strike of two years ago is still fresh in the memory of the people. They have acted in similar manner in every recent struggle between capital and labor in the great Keystone State, planting hatred and vengeance in the heart of the populace, and leaving devastation, ruined homes, and orphaned children in their wake. These modern Janisaries superseded by force of arms local administrations, usurped their jurisdiction, and established a veritable red reign of terror. The sovereign authority of Pennsylvania indeed became the Pinkerton of the industrial despots. But the wind that plutocracy and the State sowed is already beginning to bear fruit. The whirlwind is approaching.

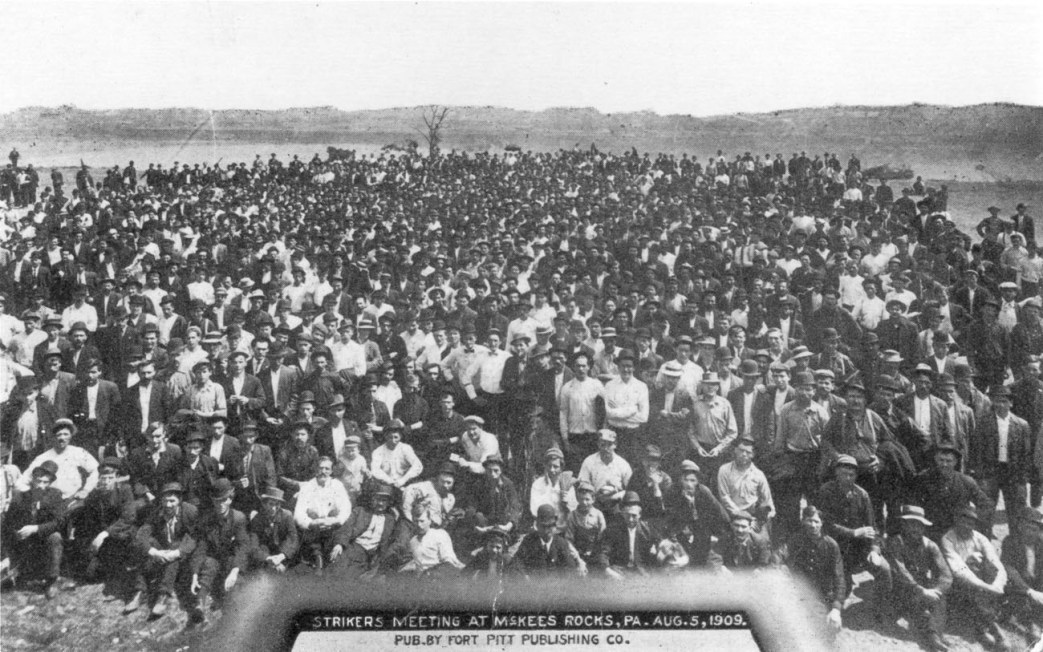

Properly speaking, there can be no such thing as an unjust strike. The exploited are always justified in resisting their despoilers, by every means at hand. But if never a strike was justified, that at McKees Rocks was imperative. It would be impossible to exaggerate the terrible conditions prevalent in the Pressed Steel Car Company’s mills. The oppression of the workingmen became so great that a strike proved the sole alternative. When it is considered that the strikers were not organized and that they were nearly all recent immigrants—Poles, Hungarians, and Greeks—it will be realized that the resort to a strike must have indeed been the only hope left.

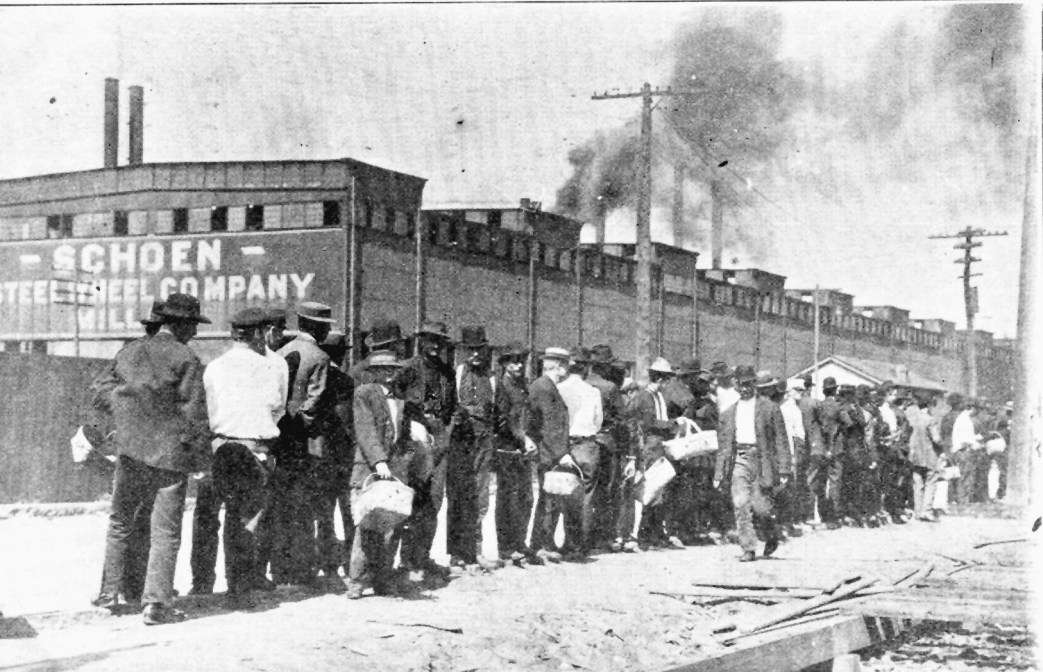

The working conditions in the mills are incredible. The employees were practically the slaves of the company. Peonage was the established system. It is euphoniously called the Baldwin contract or “pooling” method. It consists in parceling out of lots of work to a foreman, who contracts to do it for a certain sum, the amount to be divided pro rata among the men under him. This system is as fatal to the interests of the employees as it is beneficial to the company. The latter determines arbitrarily the price it will pay for a car, and then apportions the same among the gang foremen of the different departments. All spoiled material is charged up to the pool; that is, to the workmen who are lumped together in the group making a given car. All blunders of foremen, all the avoidable and unavoidable accidents of construction, are charged up against the pool. No workman knows, till he gets his pay check, how much he is going to receive; and then it is usually so little as to be hardly worth wondering about. Here is a sworn statement of a series of pay checks received by these men who are being “protected against pauper labor”:

The lowest wages, the worst working conditions, the most brutal treatment designed to deaden every human impulse and instinct, graft, robbery and even worse, the swapping of human souls, the souls of women, for the lives of their babies, have for years marked the Pressed Steel Car Works as the most outrageous of all the outrageous plants in the United States. The “slaughter house” is the most expressive name that could be given to the plant, although it has other claims to rank as a strong side show of Inferno. Workingmen are slaughtered every day; not killed, but slaughtered. Their very deaths are unknown to all save the workers who see their bodies hacked and butchered by the relentless machinery and death traps which fill the big works. Their families, of course, know that the bread stops coming. But the public, and even the coroner, are ignorant of the hundreds of deaths by slaughter which form the unwritten records of the Pressed Steel Car Plant. These deaths are never reported. The men are unknown by name except to their families and their intimates. To others they are known as “No. 999” or some other, furnished on a check by the “slaughter house”? company for the convenience of its paymasters. A human life is worth less than a rivet. Rivets cost money.

It is against these conditions that the workers of McKees Rocks rebelled. Endurance had reached its utmost limit, and yet the company refused to abolish the pool system and turned a deaf ear to the prayer for arbitration. But starving in idleness could be no worse than starving at work. Thus the men were forced to strike. And here let it be noted that the five thousand strikers entirely lacked any organization, while the only men who remained at work were those employed in the “crane and tool department,” a machinist local and member of the American Federation of Labor. These “union” men continued to serve their masters till the tying up of the other departments forced them to join the strikers.

The ever-ready capitalist tool, the State, hastened to the aid of the atrocious Steel Car Company. The rebellious spirit of the workers had to be broken, the men forced back into their slavery, and an object lesson taught to dissatisfied labor at large. The constabulary proceeded to do their bloody work, rivaling the methods of Russian Cossacks. They clubbed to death and shot to kill; they broke up the strikers’ homes, evicting sick women and suckling babes into the cold of the night. The bloodhounds of greed and power left nothing undone to break the strike, perpetrating unspeakable outrages and ruthlessly sacrificing workmen’s lives.

Against these terrible odds the strikers have now withstood almost two months. Perhaps there is not another instance in the whole history of this country’s labor movement of such a wonderful struggle of labor against capital. Unorganized, without friends or money, these despised “foreigners” have single-handed fought the rich and powerful Steel Car Company, with its private police, State constabulary, strike-breakers, and—last, but not least—its subsidized press. Nor did these brave strikers have to battle against their enemies alone. Alleged friends, organized workers, made stupid by their antiquated union tactics, directly aided the cause of the masters. Indeed, good “union” engineers, firemen, brakemen, and telegraph operators brought the murderous Cossacks and the scabs to McKees Rocks, and the National Executive of the American Federation of Labor turned a deaf ear to the cries of their bleeding comrades. Great indeed were the odds against these victims of modern slavery. But yet greater was their courage, their determination and loyalty, and faithful and staunch were their women folk, battling side by side with their husbands, sweethearts, and brothers, encouraging and inspiring.

The world loves a good fighter. The heroism of the striking McKees Rocks slaves has conquered the respect and admiration of the world. They have won a greater victory than the mere recognition of their demands by the Pressed Steel Car Company. They have destroyed the myth of their undesirability as members of a labor union. Their self-sacrifice and endurance, determination and courage, above all the supreme spirit of solidarity, prove them far better, truer union men, unorganized though they are, than the A.F.L. scabs. Nay, more: the spirit of resistance on the part of these “foreigners” will burn with letters of fire the lesson of rebellious manhood into the dull brain of reactionary wage slaves, forever prating of harmony and peace.

Labor pays dearly for every experience. But the precious blood shed by the heroic victims at McKees Rocks will fertilize the soil whence will spring a new, intelligent, revolutionary labor movement in this country. For such events as are now happening in Pennsylvania will tend to awaken American unionism from its capital-and-labor-harmony nightmare. It will learn that capitalism means abject slavery and slaughter for the workingman; that there can be neither harmony nor peace between master and slave; that the struggle is one of life and death, and that any and all means are justified in such a struggle. The masters have long since recognized and applied this self-evident truth. Only stupid labor still stammers, “Peace, peace,” where none is possible.

It has taken untold suffering, tears, and blood to teach the men of toil their first union lesson of organization. McKees Rocks will further teach them that the pillar of our boasted “liberty” is labor’s slavery, supported by bull-pen and rifle diet. McKees Rocks is the nation in miniature. It will require repeated McKees Rocks to drill the wage slave in the second lesson of his emancipation: industrial organization, cooperation, and revolution through Direct Action and the General Strike.

Mother Earth was an anarchist magazine begin in 1906 and first edited by Emma Goldman in New York City. Alexander Berkman, became editor in 1907 after his release from prison until 1915.The journal has a history in the Free Society publication which had moved from San Francisco to New York City. Goldman was again editor in 1915 as the magazine was opposed to US entry into World War One and was closed down as a violator of the Espionage Act in 1917 with Goldman and Berkman, who had begun editing The Blast, being deported in 1919.

PDF of full issue: https://archive.org/download/mother-earth/Mother%20Earth%20v04n07%20%281909-09%29%20%28-covers%20Harvard%20DSR%29.pdf