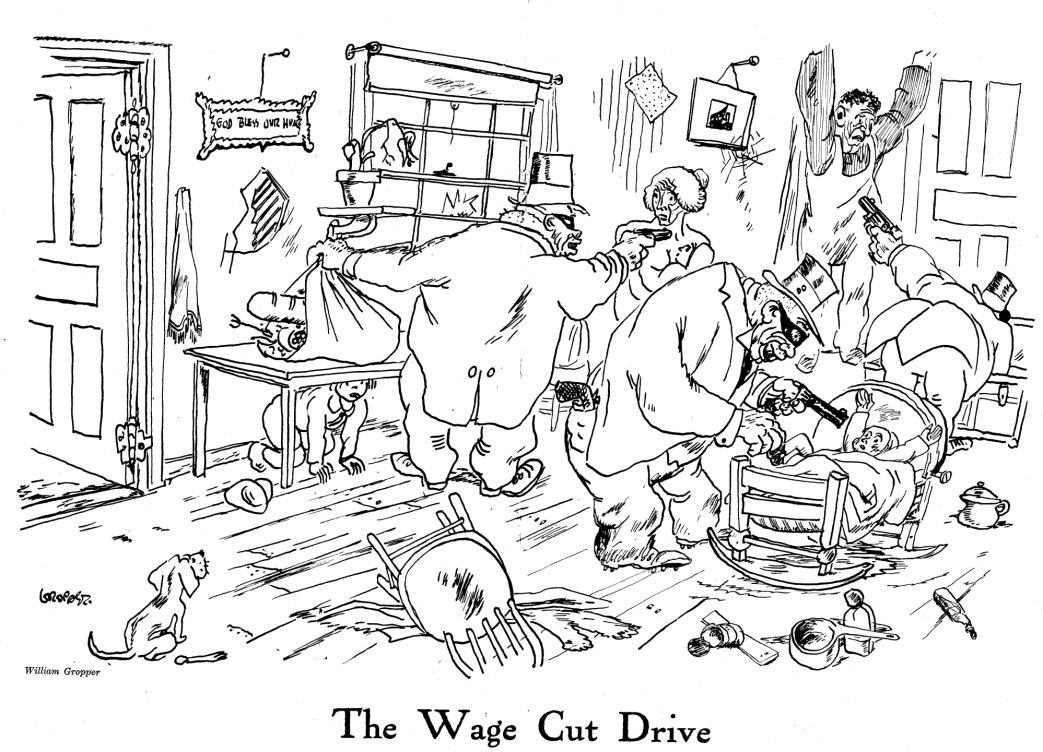

‘Marxian Economics: The Division of Surplus Value’ by Mary E. Marcy from the International Socialist Review. Vol. 17 No. 8. February, 1917.

IN the first lessons on economics we learned that profits come from the surplus value produced by the working class, that is, from value created by the productive workers for which they receive no equivalent. We saw that these workers receive a portion of the value of their products, but only a small portion of that value. We saw how the workers receive the value of the one commodity they have to sell — their labor power, but the value of their labor power is only a small part of the value of their products.

We did not discover what becomes of this surplus value. We saw that it was appropriated by the employer of the productive workers, but we did not learn what ultimately became of it.

Let us consider the capitalist who uses his capital in putting up a furniture plant and who employs men and women to make furniture. We see that these employees may receive only two dollars for making commodities that may retail to the final purchaser at something over twelve dollars. What we want to know is what has been done with the difference between what the furniture makers receive and what the furniture sells for on the retail market. Suppose the employer pays $2 for the lumber, or raw material, including transportation to his factory, or the value. of the raw material and that transportation. Transportation to the ultimate buyer is also represented in the price ‘he, the consumer, pays; but there probably remains something like $8 which has been appropriated by the factory owner or owners. What becomes of this? The Massachusetts factory owners proved satisfactorily to the United States Government experts that the salaries and wages they paid for one year amounted to just about the same as the profits of these corporations. Of course their wage lists included presidents and vice-presidents and other high officers whose duties were merely nominal. As a matter of fact, however, they proved and almost every other manufacturer could likewise show that they do not keep the $8 appropriated out of the value created by their employees.

If you will look closely into the matter you will see that almost the entire superstructure of society, at least that portion which does not in itself produce any value, does not add any necessary labor or service— is supported out of this value taken from the original producers; out of surplus value, as Marx calls it.

We have taken for granted all along that all commodities exchange at their values. And this is largely true when we consider the final purchaser — the actual consumer. On the average, he buys things at their value. The manufacturer buys raw material, on the average, at its value. The working class sells its labor power at its value, generally; sometimes a little above, sometimes a little below, but on the average, at its value (that is, at the social labor power necessary to produce it).

Part of this surplus value goes to the banker, who permits the industrial capitalist the use of the bank deposits. And out of this interest the banker, in turn, pays his clerks the value of their labor power — or two or three hours of labor value — and receives from them eight hours of labor or of service. The banker draws his actual profits, or interest, and the bank clerks are all paid out of the surplus value originally appropriated from the productive worker.

The industrial capitalist also divides the surplus value extracted from the factory producers with the advertisers. Millions and millions of dollars are annually paid to the different advertising agencies, the newspapers, the illustrators, the printers, the magazines, the clerks, the $50,000-ayear advertising specialists, etc. The magazines and newspapers are supported by such advertising.

Again, the industrial capitalist, the furniture manufacturer, divides with the governments. He pays property taxes, income taxes and duties. He pays something to the land owner — rent for necessary land. And then he sells the commodities produced by the furniture makers to the wholesalers below their value. In other words, he divides what he has taken from the productive workers with the wholesale merchants.

The wholesale companies produce no value. They are almost wholly unnecessary, perform no useful service. And again the wholesale company divides with the banks which lend them capital, and with the big advertisers, and contributes also to the governments by paying taxes, etc.

The wholesale merchant is much in the same position as the broker who sits in his office and writes to prospective buyers. This broker creates no value. He is nearly always wholly unnecessary, useless, to society. He finds customers and buys from the factory owner or from the farmer, who sell him their commodities below their value. He may even never see the wheat or furniture or corn that he buys. He rarely does see them. The broker merely writes the factory or the farmers to ship the grain or the furniture to his customer. He sells commodities to his customers at their value. He buys commodities below their value.

The wholesale merchant invests his own capital, and capital borrowed from the banks, in large stocks of goods; he employs thousands of clerks, shipping clerks, office employes, advertising men. And all this, all these men and women, and the profits of the wholesalers, the bankers, the advertisers, are paid out of the surplus value appropriated from the industrial workers.

In “Value, Price and Profit” (Kerr edition, pages 89-91), Marx says:

“The surplus value, or that part of the total value of the commodity in which the surplus value or unpaid labor of the working man is realized, I call Profit. The whole of that profit is not pocketed by the employing capitalist. The monopoly of land enables the landlord to take one part of that surplus value, under the name of rent, whether the land is used for agriculture, buildings or railways, or for any other productive purpose. On the other hand, the very fact that the possession of the instruments of labor enables the employing capitalist to produce a surplus value, or what comes to the same, to appropriate to himself a certain amount of unpaid labor, enables the owner of the means of labor, which he lends wholly or partly to the employing capitalist — enables, in one word, the moneylending capitalist to claim for himself under the name of interest another part of that surplus value, so that there remains to the employing capitalist as such only what is called industrial or commercial profit.

“By what laws this division of the total amount of surplus value amongst the three categories of people is regulated is a question quite foreign to our subject. This much, however, results from what has been stated.

“Rent, Interest and Industrial Profit are only different names for different parts of the surplus value of the commodity, or the unpaid labor enclosed in it, and they are equally derived from this source, and from this source alone. They are not derived from land as such or from capital as such, but land and capital enable their owners to get their respective shares out of the surplus value extracted by the employing capitalist from the laborer. For the laborer himself it is a matter of subordinate importance whether that surplus value, the result of his surplus labor, or unpaid labor, is altogether pocketed by the employing capitalist, or whether the latter is obliged to pay portions of it, under the name of rent and interest, away to third parties. Suppose the employing capitalist to use only his own capital, to be his own landlord, then the whole surplus value would go into his pocket.

“It is the employing capitalist who immediately extracts from the laborer this surplus value, whatever part of it he may ultimately be able to keep for himself. Upon this relation, therefore, between the employing capitalist and the wage laborer the whole wages system and the whole present system of production hinge.”

All this is as true of the retail merchant as it is of the wholesale companies. Neither produces any value? nor do their employes produce any value. In almost every small town we see, for example, half a dozen struggling dry goods stores, two or three shoe stores, five or six groceries.

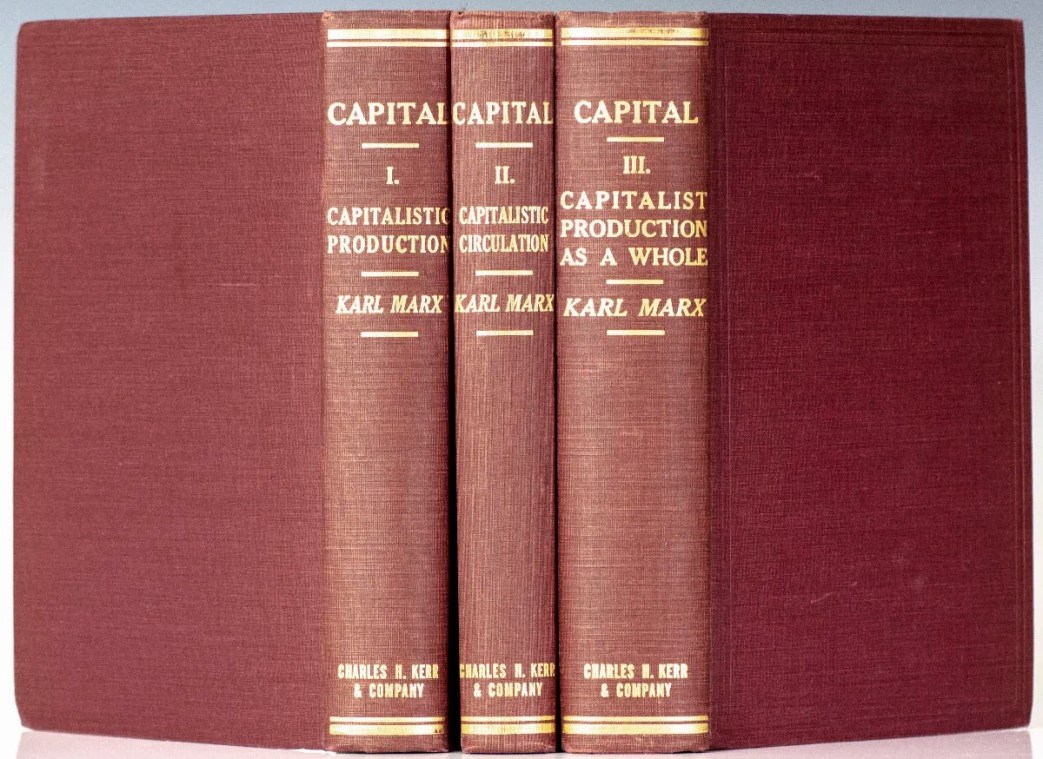

On the foot of page 329 of Kerr edition of “Capital” Vol. Ill, Marx says:

“Merchant’s capital does not create any value, or surplus value.”

And again at the foot of page 331:

“Seeing that merchant’s capital itself does not produce any surplus value, it is evident that surplus value appropriated by it in the shape of average profit, must be a portion of the surplus value produced by the total productive capital. But the question is now: How does the merchant’s capital manage to appropriate its share of the surplus value or profit produced by the productive capital?”

On page 345 he explains:

“The merchant’s capital appropriates a portion of the surplus value by having this portion transferred from the industrial capital to itself.”

And again on page 346 Marx says:

“Just as the unpaid labor of the laborer of the productive capital (in this case of the furniture manufacturer) creates surplus value for it in a direct way, so the unpaid labor of the commercial wage workers (clerks, salesmen, etc., etc.), secures a share of this surplus value for the merchant’s capital.”

(Read the chapter on Commercial-Profit, beginning on page 330, Vol. Ill, “Capital.”)

Now, going back to the furniture manufacturer again, or taking the example of a shoe or hat or clothing manufacturer: it is often necessary to show the wares, to fit the shoes or match the cloth. This is what the employes of some retail merchants actually do. They are merely selling agents for the shoe, or cloth, or furniture manufacturer. They produce no value, or surplus value. Some of these perform a necessary function. Marx calls this a part of the necessary expenses of circulation, paid for out of the surplus value produced by the workers in the industry.

(Read the chapter on The Expenses of Circulation, Vol II, Marx’s “Capital,” Kerr edition, which starts on page 147.)

Questions

1. What is surplus value?

2. Who produces surplus value? What class of workers?

3. Suppose one manufacturer sells his commodities right at his factory, and another manufacturer sells his from retail stores at Oshkosh and Indianapolis and many other retail stores, would the clerks in the Oshkosh or Indianapolis stores perform the same function as the sales clerks who sold goods at the factory?

4. Outside of necessary transportation, would these commodities be any more valuable in Indianapolis than at the factory?

5. Would these clerks perform a necessary function?

6. Would they add any actual value to the commodities?

7. What happens when a manufacturer makes double the average rate of profits?

8. Are other capitalists attracted to the same industry?

9. What causes an average rate of profits?

10. From where does the money come which is made by a broker in hoops and staves and barrels, who buys from the manufacturers and has these commodities shipped direct to his customers? Does he add any value to them? If he sells them at their value to the consumer, where does he get his profit?

The International Socialist Review (ISR) was published monthly in Chicago from 1900 until 1918 by Charles H. Kerr and critically loyal to the Socialist Party of America. It is one of the essential publications in U.S. left history. During the editorship of A.M. Simons it was largely theoretical and moderate. In 1908, Charles H. Kerr took over as editor with strong influence from Mary E Marcy. The magazine became the foremost proponent of the SP’s left wing growing to tens of thousands of subscribers. It remained revolutionary in outlook and anti-militarist during World War One. It liberally used photographs and images, with news, theory, arts and organizing in its pages. It articles, reports and essays are an invaluable record of the U.S. class struggle and the development of Marxism in the decades before the Soviet experience. It was closed down in government repression in 1918.

PDF of full issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/usa/pubs/isr/v17n08-feb-1917-ISR-riaz-ocr.pdf