‘The Anti-Labor Courts’ by Clarissa S. Ware from Labor Herald. Vol. 2 No. 5. July, 1923.

NAPOLEON one said: “God is on the side of the strongest battalions.” Whether this be so or not, it can certainly be said with truth that Justice is on the side of the class which controls the state. We may place a statue of Liberty with a flaming torch at the entrance to New York harbor to flash forth its greeting of hypocricy, but the new-comers soon learn what the native workers now know, that the law of the land is against them. The scales of Justice are not equally balanced.

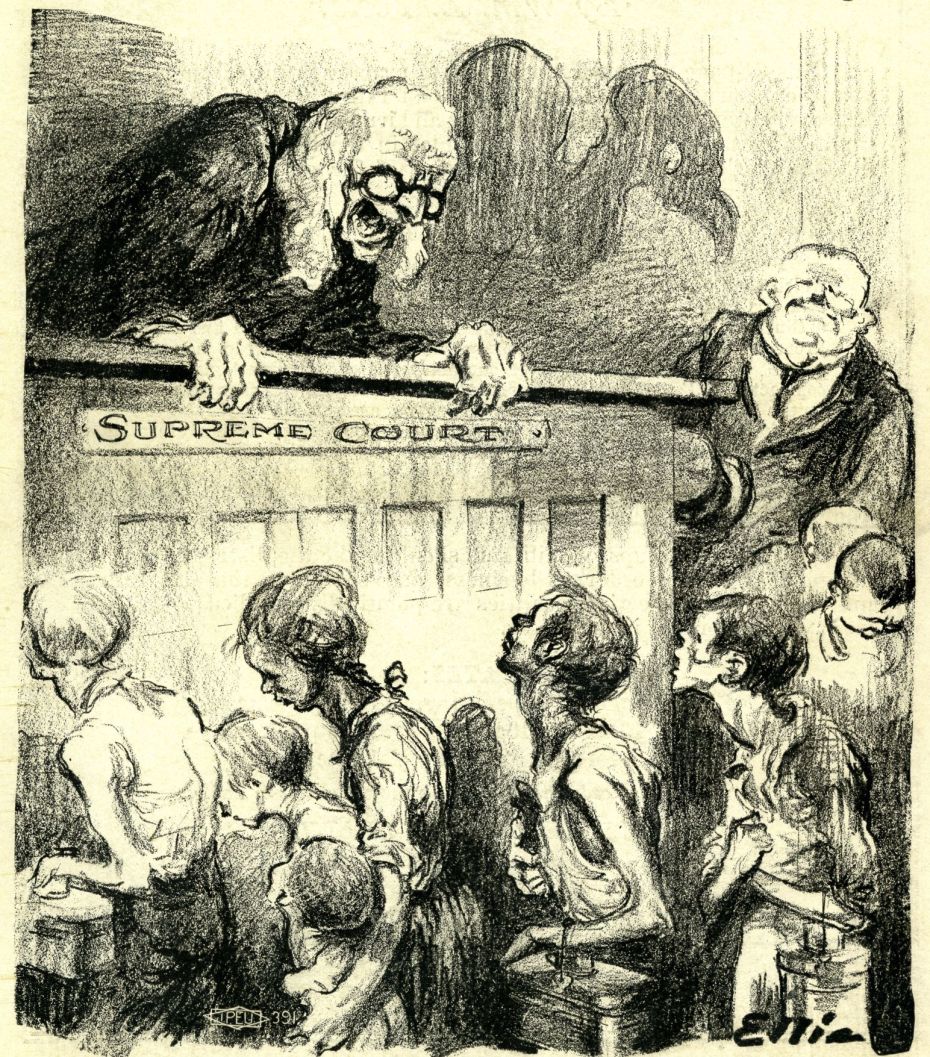

In 1916 the effort to regulate and ameliorate the crying abuses of child labor resulted in the passage by Congress of an act forbidding the movement in interstate commerce of the products of a child under 16 years of age. This law was bitterly opposed by the employers of child labor. Early in 1918, the “impartial” courts declared it unconstitutional.

“Justice” Prevents Child Protection

A year later, in a further effort to limit the exploitation of children which had been sanctioned by the Supreme Court, the Child Labor Tax Law was passed as part of the revenue act of February 24, 1919. This placed a tax of 10% on the net profits of any employer using the labor of children otherwise than according to certain standards, similar to those of the act of 1916. But the wisdom of the blind justices was again called upon. The scales dipped again in favor of the exploiters and against the children. “A court must be blind,” said the decision, “not to see that the so-called tax is imposed to stop the employment of children.” Such encroachment upon the privileges of profit-making is not within the power of the law-making body, the court decided, and in 1922, the act was declared unconstitutional.

With unfailing regularity, constitutional provisions are applied one way for the employing class and another way for the workers. Regulations established by law, prohibiting the employment of aliens on public works, have been upheld; while regulations prohibiting the employment of non-union labor is found unconstitutional. The difference between the two cases is, that the first breaks up the solidarity of the workers, and is therefore permitted; the second assists in organizing the workers, and is therefore not permitted. The Supreme Court writes the law, through its interpretations, and writes it in the interests of the capitalist class, the masters of the State.

The law is very severe with workers who are guilty of misrepresentation or false pretences against the employers. But when an act was passed in Illinois, which declared it unlawful for an employer to transport workmen from another State or locality under misrepresentation or false pretenses as to kind and character of the work, failure to give notice of a labor dispute being declared to be misrepresentation, it was shortlived. The employers’ interests were threatened. The Supreme Court of the State wiped it off the books by declaring it unconstitutional.

Railroad Labor and Court-Made Law

The history of unionism on the railroads is replete with instances of the use of the courts against the workers. In connection with the Pullman strike in 1895, Eugene V. Debs and others were enjoined from doing anything calculated to interfere with the carrying of the mails or with the movement of interstate commerce. Under this sweeping injunction all labor union activity was prohibited. Because Debs and his associates would not abandon their struggle for the workers, the Court ordered them to jail for “contempt.” The Supreme Court was called upon to rule on the right to issue such an order. The ruling was in favor of the employers. The American Federationist said of it (Vol. II, p. 68): “The decision of the United States Supreme Court in the Debs case is the worst ever made by such a court, so far as the interests of Labor are concerned.”

The Debs case, which set the pace in the application of injunction law to the workers, has been followed by a long series of similar ones. Today the subject of the injunctions in labor disputes is a specialized branch of law, with a whole library of books about it. In the Erdman Act, for example, passed in 1898, a section prohibited the discharge of an employee on account of union membership. The case of one Coppage, discharged by the L. & N. Railway, was taken to the Supreme Court, which ruled the law unconstitutional. The Railroad Trainman, March, 1908, said of this decision:

“Another stunning decision has been given by the Supreme Court…Just what law intended to take care of the people against the unfairness of their employers that is not ‘repugnant to the constitution’ remains to be discovered…The employee must abandon his only way of protecting him-self against his employer. The decision against membership of a man in his labor union is ample evidence of that.”

The Supreme Court is able to stretch its constitutional law in a most remarkable manner. The Adamson 8-Hour Law was found to be constitutional—a thing surprising only if one forgets that it came at a moment when the railroad unions held tremendous power and threatened a strike. A further factor assisting the Adamson Law to pass the constitutional barriers was the fact that it was considered an entering wedge for a compulsory arbitration law to follow.

Why does the cause of the workers weigh so lightly in the scales of “Justice”? Because the capitalists, the employing class, control the entire Government. They control it and they use it and all its branches, including the courts, as weapons of attack against the organizations of labor. The only way to change this condition is to change the control of the Government. The American Labor movement must learn to use its political power. It must take into its own hands the making and enforcing of the law.

The Labor Herald was the monthly publication of the Trade Union Educational League (TUEL), in immensely important link between the IWW of the 1910s and the CIO of the 1930s. It was begun by veteran labor organizer and Communist leader William Z. Foster in 1920 as an attempt to unite militants within various unions while continuing the industrial unionism tradition of the IWW, though it was opposed to “dual unionism” and favored the formation of a Labor Party. Although it would become financially supported by the Communist International and Communist Party of America, it remained autonomous, was a network and not a membership organization, and included many radicals outside the Communist Party. In 1924 Labor Herald was folded into Workers Monthly, an explicitly Party organ and in 1927 ‘Labor Unity’ became the organ of a now CP dominated TUEL. In 1929 and the turn towards Red Unions in the Third Period, TUEL was wound up and replaced by the Trade Union Unity League, a section of the Red International of Labor Unions (Profitern) and continued to publish Labor Unity until 1935. Labor Herald remains an important labor-orientated journal by revolutionaries in US left history and would be referenced by activists, along with TUEL, along after it’s heyday.

PDF of full issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/usa/pubs/laborherald/v2n05-jul-1923.pdf