Wonderful vignettes from the strike by Robert W. Dunn, Margaret Larkin, John Dos Passos, Esther Lowell, Grace Lumpkin, Norman Thomas, Arthur Garfield Hays, and Marguerite Tucker.

‘A Passaic Symposium: Snapshots of the Textile Strike’ from the New Masses. Vol. 1 No. 2. Junes, 1926.

INTRODUCING AN EPIC

This Passaic strike that America has been reading about was precipitated when the millionaire employers tried to cut the wages of their workers ten per cent — the wages of family men and women earning only $12 to $20 an overlong working week.

The strike has lasted for nearly three months, and has become one of the heroic epics of American labor history, like Homestead, Ludlow, Cabin Creek, Lawrence and Seattle. It will never be forgotten, nor will the brave workers who have marched on its picket-lines.

The Passaic strike may be settled when this issue of the New Masses reaches its subscribers. But the problems of the million workers in the textile industry will not have been settled. They are still living in foul tenements, eating scant food, raising starved families on pauper wages. They are still at the mercy of boss-owned judges, mayors and police. They are still unorganized and helpless.

The symposium printed here consists of snapshots of the Passaic strike by New York liberals and radicals, who were stirred from their usual occupations by the strike, and went out to Passaic to show their solidarity with the workers.

Some of them were arrested, others were a trifle manhandled, and all of them learned a great deal about the of justice handed out to workers who strike.

The New Masses salutes these public-spirited “agitators” as well as Rabbi Stephen S. Wise, Elizabeth Curley Flynn, Clarina Michelson, Freda Kirchwey, Forrest Bailey, Justine Wise, Mary Heaton Vorse and others who have thrown themselves gallantly into the fight.

From one angle this Passaic strike has been the most heartening event in years. It has dispelled the cloud of pessimism and defeatism that hung over the radical movement since the vast calamity of the war. It has united the different sections of the movement on a vital issue. It has proved that cynicism and Menckenism have not conquered all the free minds in America. Justice still has friends in this country.

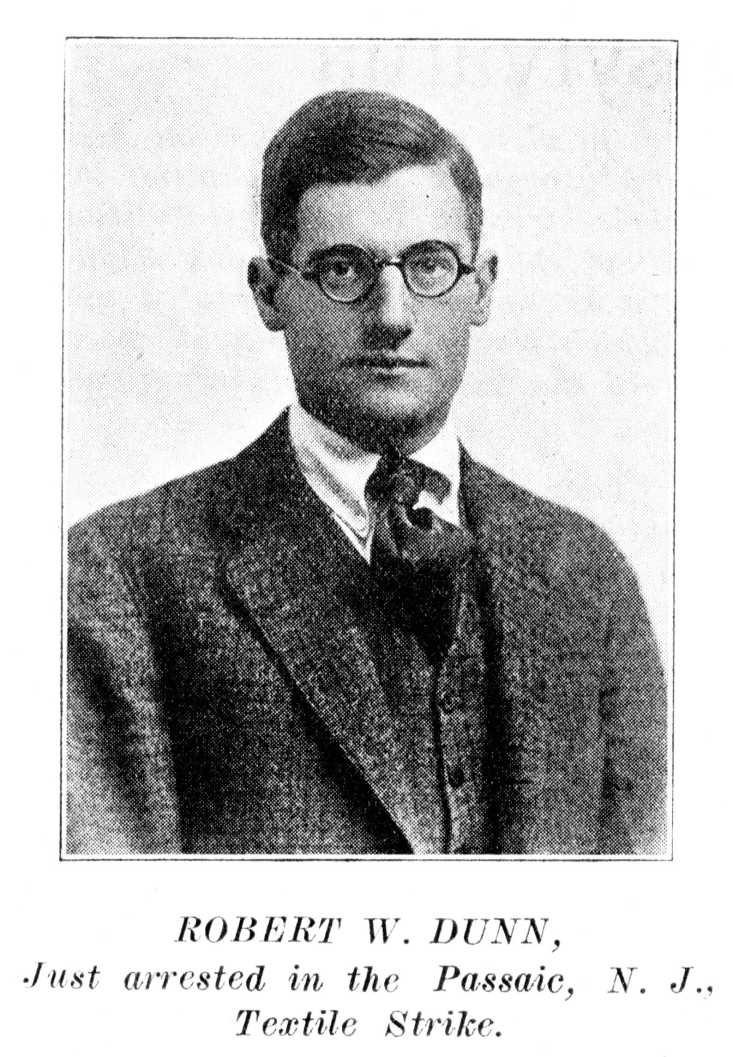

PROFESSIONAL PATRIOTS by Robert Dunn.

PROFESSIONAL “outside agitators” for the RED-WHITE-AND-BLUE also horned in on the Passaic strike. The cops, the magistrates, the German mill owners and other monopolists of Americanism greeted them with loud hosannas and hallelujahs. Rotary, Kiwanis and Chamber of Commerce extended them a warm and a glad mit.

Like the Gideon brethren distributing black-bound Testaments came first the United States Patriotic Society with copies of the CONSTITUTION in Slavonic, Hungarian and Arabic. They came to save the souls of the heathen strikers from red, rank Bolshevism. They came — their expenses paid by their “founder,” Mr. Jacob Cash, — to teach a constitution which omits the Bill of Rights, the clauses about free speech, assemblage, unreasonable search and seizure, excessive bail. An expurgated constitution with the objectionable, indecent and revolutionary passages clipped. This is their remedy for low wages and long hours. They also distribute “Founder” Cash’s little idyll — “What America Means to Me” — which is calculated to make the clubbed, gassed and half-starved workers think well of our INSTITUTIONS and swear allegiance to the government of Zober, Preiskel & Co.

There also came the patriotic and uplifting National Security League with its 100 per cent Wall Street support. It placed articles in the local press glorifying the American Cossacks. Its orators addressed luncheons of business men and painted Weisbord scarlet. They advised the civil and military dictators during the days of the terror. They cooperated with mill stool pigeons and provocateurs in arresting, enjoining and framing up the strike leaders.

One of their business agents, J. Robert O’Brien, tried a little of his fraudulent patriotism on me while I was confined in the Garfield hoosegow. He had me led out to a room where he and a local bull faced me alone. First this professional red smeller pretended to have met me before. I corrected his memory. Then he said, “I wanted to ask you about that article you wrote for the Daily Worker calling me a strike-breaker.”

I replied that I had never mentioned him in any article anywhere at any time.

“Perhaps it was some other paper, or perhaps a speech,” he teased.

At this point I suggested that a “witness for the defense” be permitted in the room if he wished to carry on a debate, or better still he might come to my office later in the week for a full discussion under conditions more conducive to frank expressions.

“This seems to be your office at present,” sneered Mr. O’Brien. “I merely wanted to get your vision of communism and the strike.”

Vision was the word this fascist used.

I suggested that my attorney, if I had any (the police officials had tricked him away from my hearing before the magistrate) be called in as a witness. At this point the patriot decided I was hopeless and the dicks opened the door and escorted me back to my cell.

…. If O’Brien insists on my opinion of him I hereby charge him with being a stalwart upholder of the Bergen County conception of law and order. I also charge him with being a strike-breaker.

200 N.Y. AGITATORS REACH PASSAIC by John Dos Passos.

THE people who had come from New York roamed in a desultory group along the broad pavement. We were talking of outrages and the Bill of Rights. The people who had come from New York wore warm overcoats in the sweeping wind, bits of mufflers, and fluffiness of women’s blouses fluttered silky in the cold April wind. The people who had come from New York filled up a row of taxicabs, shiny sedans of various makes, nicely upholstered; the shiny sedans started off in a procession towards the place where the meeting was going to be forbidden. Inside we talked in a desultory way of outrages and the Bill of Rights, we, descendants of the Pilgrim Fathers, the Bunker Hill Monument, Gettysburg, the Boston Teaparty…Know all men by these presents…On the corners groups of yellowish grey people standing still, square people standing still as chunks of stone, looking nowhere, saying nothing.

At the place where the meeting was going to be forbidden the people from New York got out of the shiny sedans of various makes. The sheriff was a fat man with a badge like a star off a Christmas tree, the little eyes of a suspicious landlady in a sallow face. The cops were waving their clubs about, limbering up their arms. The cops were redfaced, full of food, the cops felt fine. The special deputies had restless eyes, they were stocky young men crammed with pop and ideals, overgrown boy-scouts; they were on the right side and they knew it. Still the shiny new double-barreled riot guns made them nervous. They didn’t know which shoulder to keep their guns on. The people who had come from New York stood first on one foot then on the other.

Don’t shoot till you see the whites of their eyes…

All right move ’em along, said the sheriff. The cops advanced, the special deputies politely held open the doors of the shiny sedans. The people who had come from New York climbed back into the shiny sedans of various makes and drove away except for one man who got picked up. The procession of taxis started back the way it had come. The procession of taxis, shiny sedans of various makes, went back the way it had come, down empty streets protected by deputies with shiny new riot guns, past endless facades of deserted mills, past brick tenements with ill-painted stoops, past groups of squat square women with yellow grey faces, groups of men and boys standing still, saying nothing, looking nowhere, square hands hanging at their sides, people square and still, chunks of yellowgrey stone at the edge of a quarry, idle, waiting, on strike.

READ THE RIOT ACT! by Marguerite Tucker.

“FELLOW-WORKERS, they tell us we can’t picket the mills. Well, we’ll show them. There are some hard-hearted young women over from New York and they want to lead the picket line. They don’t care how long it is — from here to hell if necessary. How about it? Shall they lead it?”

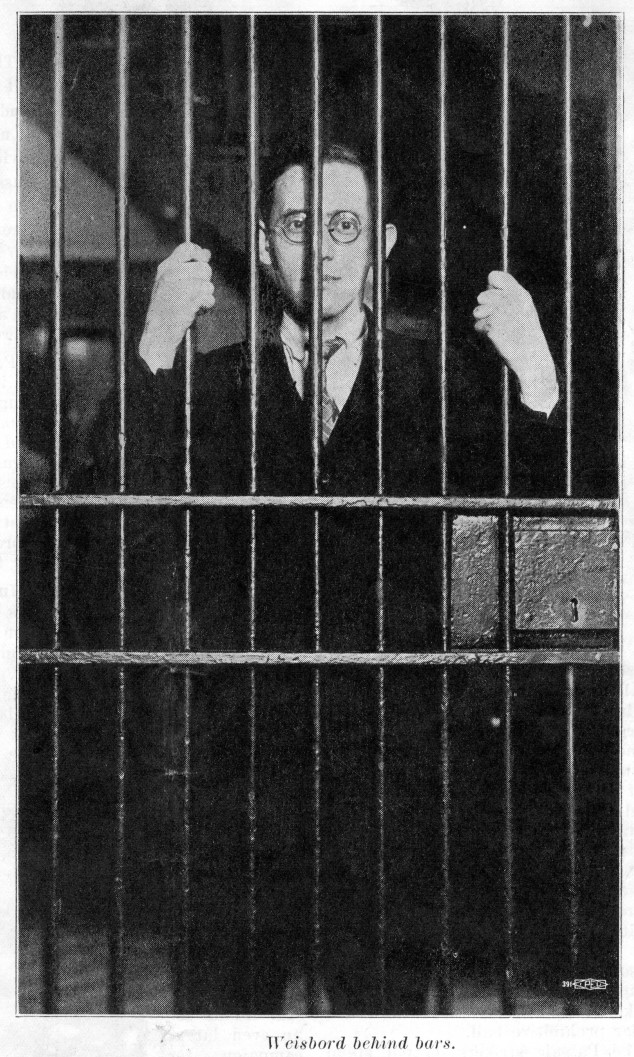

A roar of assent boomed over the tree-tops. Robert Dunn, tall, lanky, with a kind of Yankee charm, reminiscent of Connecticut patriots, stood on the open air platform. Five thousand striking textile workers gathered round, listening intently to every word. This was the twelfth week of the strike. Albert Weisbord, their leader, arrested a few days before, was expected any moment.

The authorities had tightened up. “No picket line today,” were the orders. Well-fed detectives, in smart spring coats, mingled with the crowd…Hazy, little clouds swayed across the pale spring sky.

Five minutes later, the picket line streamed along the Passaic river. The Botany Mills on the opposite side looked like an arsenal. Thousands of empty cans and refuse littered the river bank.

The line strung out a mile behind us. We walked quietly two by two. Children darted in and out like dusty little butterflies, faces full of cheerful anxiety; young girls with glittering eyes and strong white teeth, burst into revolutionary songs. At one moment, the entire line took up the transport workers’ song, “Hold the Fort,” and sang to the beat of rhythmic feet. We turned the corner leading past the Forstmann & Huffmann mills. A quiver, like the ripple down a snake’s back, ran through the line.

Ahead of us, in rows awaiting our coming, stood armed policemen. Officers, with clubs, on motorcycles suddenly dashed out of a side street and rushed up and down the picket line. No disorder on our part. But we were picketing the Forstmann & Huffmann mills against orders…thousands of us. A young striker headed the line. A figure stepped out of the line of policemen and walked up to the young striker. It was Sheriff Nimmo of Bergen County. A few words between our leader and the sheriff. Then, Nimmo, with fingers fumbling with fury, plucked a document from his pocket and taking a stand apart from us of the silent picket line, who were watching him curiously, he shrieked:

“I am going to read the Riot Act.”

It would be cruelty to animals to compare his face, at this moment, to an animal’s. He looked like a hideous mask; venom and hate flowed over his countenance. He finished “God save the state Sweep ’em up.” He emphasized the command with a furious gesture to the policemen.

Like automatons, they swept into the line with ready clubs. Blows right and left, on heads and shoulders. Women fell to the ground. Esther Lowell stooped to pick up a woman and was arrested on the spot. The sheriff spied pretty Nancy Sandowsky, girl picket leader, who had already been arrested several times. He yelled, “Arrest that girl.” Nancy, speechless, was forcibly led away.

Robert Dunn was walking beside me. A man in front got a blow on the head that should have killed him. The policeman turned savagely and faced us. He scanned us hastily and rushed by us. We looked respectable, I suppose. I looked round. He was striking a man who was trying to rise to his feet. Dunn left me for a few minutes. I saw Dunn being led up the street by a policeman.

The line was broken. Armed deputies with sawed-off riot guns were driving the workers to a vacant lot. Policemen with clubs pushed threateningly. The patrol wagon stood at a corner. One by one our friends mounted the steps, arrested for God knows what. The whole thing was over in a flash.

Unarmed strikers singing songs…with nothing in their pockets but their hands, marching cheerfully, and Heaven knows they had nothing to be cheerful about. The crescendo: infuriated policemen with heavy clubs plowing into them, savagely striking every head they saw. The finale: a big black wagon carrying off strikers to the jail.

If there is one thing that has impressed me in this Passaic strike, it is the viciousness and brutality of the law on one side and the sturdy, disciplined spirit of the strikers on the other. The sight of thousands of faces looking up as you stand on the platform is deeply appealing. Their trust almost hurts. Chunky peasant faces, old women with black handkerchiefs tied round their chins; young girls, fresh and beautiful despite what the mills have done to them; mothers with babies in their arms; men standing at the back of the hall, muscled, solid, quietly attentive. They follow every word of the speakers and friendly applause shakes the building at irregular intervals. They love their leader, Albert Weisbord. He is young, rather small of stature, with a sensitive face and a modest manner.

This strike has power and not only power: for it has dignity and seriousness of purpose…and beauty.

JERSEY JUSTICE by Margaret Larkin.

TEDDY TIMOCHKO and Chester Grabinsky were pals in Botany mill before they went on strike. They have been friends ever since Teddy went into the mill three years ago when he was fourteen and Chester, two years older, showed him the ropes.

They went on strike together the first day of the strike and every day since they have gone to the picket line. One morning they were stopped by five cops. The cops grabbed Teddy and began to search him. Chester knew that in America cops can’t search people on the streets unless they have a search warrant, so he edged in to “give ’em an argument.” “You can’t do that,” he said. “Oh, can’t we!” said the cops. “You’re under arrest.”

“What for? I didn’t do nutten,” said Chester.

“Yeh didn’t, hey?” cried another cop, and swung his club down, “blunkblunk” on Chester’s head.

Chester was carried to the patrol wagon. When he regained consciousness the police took him to the hospital to have stitches taken. When he was nicely bandaged up he was solemnly charged in open court, in the face of all the evidence, with “interfering with an officer in the performance of his duty,” and sentenced to ten days in jail.

Nancy Sandowsky was arrested for the third time as she marched by on the picket line. Everybody in the court laughing when the judge sentenced Nancy to ten days in jail for shouting “Two-four-six-eight! who do we appreciate? Weisbord! One-two-three-four! what are you going to yell for? Union!” and for saying, “I don’t care” five times when threatened with arrest.

Frank Sorno learned something about courts for strikers one afternoon. When the thugs that are deputy sheriffs in Bergen county told the picket line to “shut up that Solidarity song,” they began to sing another one. “My country ’tis of thee, sweet land of liberty,” they sang, and if the tone was a bit derisive, whose fault was that? Frank Sorno was arrested on the word “liberty.” He began to learn something of the amazing celerity of “Jersey Justice” for strikers. Before his friends could telephone the news of his arrest to headquarters, he had been hauled up before a Justice of the Peace, arraigned and tried without counsel for his defense, found guilty and had begun serving a thirty day jail sentence! “They didn’t waste any time,” said Frank philosophically.

The Passaic strike runs its own newspaper. The strikers are proud of “The Strike Bulletin” and many of them write for it — short, direct, skeleton-like stories that are more telling than many an elaborate narrative. Frank Vacarro and Joseph Sinichuk were giving out free copies of the Bulletin one day. “You’re under arrest.” The usual hustling and manhandling. After Frank and Joe got to the station it was found that they really had been committing a heinous crime. “Found guilty of distributing advertising without a permit,” said the Judge.

Andy Bokowsky was arrested. He tried to tell his story to the Judge. He wanted to tell how he had been hit over the head, how all the strikers in the first ranks of the line had been abused as they were arrested, for nothing except for being in the front ranks. When he came before the Judge he was not allowed to tell it.

The cop testified. He told a smooth story. Andy had refused to move on, Andy had cursed him, Andy had tried to strike him; everything that the cop had done to Andy he swore that Andy had done to him. Nobody interrupted the cop. “Oh Jez, how that cop lied,” said the other boys. Andy stood at the bar “of justice,” forbidden to clear himself, and the bitter realization of his own helplessness overcame him. He didn’t mind being arrested, or being cursed, or being hit, or going to jail. It was the exasperation of being convicted by a lying cop that upset Andy. He burst into tears. “Poor Andy, he couldn’t stand it the way that cop lied,” said the boys. But the Judge was convinced that a striker who cried when the cops told lies about him must be demented. He ordered Andy held ten days in jail “for observation.”

Jack Rubenstein, picket captain, hero of many a tactic that has outwitted Passaic cops, was arrested for the fifth time, refused counsel at his arraignment, hustled off to jail, and held under heavy bond. His offense was a major one. It read otherwise in the complaint, but it may be summarized in three words, “good picket captain.” While he was in jail he fell into new crimes. A dispute in the bull pen in which he interposed earned him the usual reward of the peace maker. The jail keeper rushed in, saw Rubenstein leaning on the door of his cell and decided to fix the blame on him. “What’s the trouble here?” he cried, and without waiting for an answer began to kick and pummel Rubenstein. “No use fighting back in jail — they’ve got you licked already,” said Rubenstein. “I just backed away from him. I wish now I’d hit him, since they got me for assault anyway.” Rubenstein, after being beaten up, was charged with assault and battery.

Perhaps you think that “recourse can be had to the courts” when strikers are beaten by police after their arrest, when they are arrested on silly complaints, when they are arrested illegally, when they get misdeals in the courtroom, high bails from Justices of the Peace, and justice nowhere at all.

Hear Police Judge Davidson of Passaic when sixteen warrants against police officers on charges of atrocious assault were demanded by attorneys for the American Civil Liberties Union. “I will not allow any warrants to be issued against police when strikers are the complainants,” said the Judge. “Will you accept the complaints of these three people who are not strikers and allow your clerk to issue warrants?” asked the attorney. “I will not allow any warrants whatsoever to be issued against the police if the charges involve things they did while on duty in keeping order,” was the answer of Judge Davidson.

GOD SAVE THE STATE! by Grace Lumpkin.

SAID the policeman, swelling out his chest and swinging his club suggestively —

“What are you doing here?” “Picketing,” answered the boy.

The big man’s red, puffy face vibrated angrily to the staccato of his words. He said:

“Now, young man, you can lead this line down two blocks to your right and on back to town, but you can’t picket! You can choose to go away or you can choose trouble!”

The youngster turned around. I was just behind him and saw his eyes. They had fear way back in them, but he had whipped his lips into a twisted smile. He went down the line and spoke to the strikers.

“Fellow workers, he says we’ll have to go away or expect trouble. What do you say?”

The people answered.

The boy came back to the front of the line, looked at the policeman and said:

“We’ll picket.”

He turned to go back down the sidewalk and the long line began to follow. We took a step or two and found policemen with uplifted clubs barring our way, and behind them men with guns. Suddenly the sheriff appeared. He gathered the police about him, read the riot act which ended with the words, “God save the state.” Then, with a great sweep of his arm, he screamed:

“Sweep ’em out, boys!”

The police rushed toward the strikers. The air became thick with clubs, with cries of pain and misery, with the sound of clubs striking against human bodies. A woman and a child lying silent on the ground, a policeman standing over them, his club raised. Another woman screaming as a bluecoat struck her down. These things are unforgettable.

A law of 1864 for workers of 1926. A law enforced by great blue arms swinging clubs against human, quivering flesh. God save the state, and to hell with human beings.

IS THIS LIBERTY? by Arthur Garfield Hays.

ONE cannot conceive of a greater state of organized tyranny and disregard of law than exists in Passaic, Garfield and the rest of the strike territory. Under-Sheriff Donaldson, with apparent confidence in his position, asserts that there will be no public meetings, orderly or disorderly, in Garfield. It is almost impossible even to test the right, where twenty or thirty armed men prevent an assemblage. In spite of constitutional provisions that excessive bail should not be demanded, the courts have asked, not excessive, but exorbitant bail. For acts which at most would amount to disorderly conduct and for which men are ordinarily fined $10 to $25, bail of $5,000 to $30,000 is demanded, when the individual happens to be of any importance, or a leader in the strike. The arrests and bail have little to do with the acts because, in such cases, the acts are all the same. The obvious purpose is to break the strike by jailing leaders. A fortunate consequence is that people in this country may gradually come to realize that guarantees of liberty are gradually disappearing. I am optimist enough to believe that when the people realize this, there will be a great wave of indignation.

AN OLD FIERCE MOTHER by Esther Lowell.

HERE’S to the Passaic strikers, the workers themselves, heroes of the fight, backbone of the world! I remember this about them:

A bright brown-eyed girl stands close to the platform at the strike meeting, holding a heavy boy of four, her pale face lit with a lovely smile. Night work is making her old at twenty-five.

A stocky man with an undersized boy perched on his shoulder, listens with elephantine patience.

A sturdy man with glasses and drooping moustaches offers “a twelve room house for the first strikers put out by bad landlords,” his Italian tongue twisting the English words.

Stalwart young Negro picket captains command the mixed white and black line of strikers marching to the dye works. Soft Negro voices: “Fellow workers, keep a straight line!” An older colored man bewildered by white workers accepting colored leadership.

Glowing with the glamor and drama, thirteen-year-olders stay from school to help the fight of their fathers and mothers, their sisters and brothers. “My mother broke her finger in the mill and my sister lost hers in the machinery a week later, so my father doesn’t want me to go to work there,” says a girl. Some one comments: “She ought to go on to high school. She’s the smartest girl in the class.”

Dark passageway into bedroom, kitchen and living room of a shy little Polish widow wearing a gay old country kerchief on her head. Five children depend on her meagre earnings — $16 weekly when the mills are busy. Take out $16 a month rent for those three dark bits of space!

“I got nine childs,” a lanky German Hungarian father says. “Oldest boy, eighteen, work in stove cleaning for $15 a week.” The baby was a seven months child, now nearly three years old, and the thin nervous mother sick mostly since. “When this one come I work up to the last week,” she says, pointing to her scrawny son of five, or seven. “By this other boy, I work three months after.” Mother in the spinning department at night; father in finishing by day.

Worn-looking widow feeding a young baby on chopped cold boiled potato in a dark, damp back room. Daughter striking; no housework out now for mother; boy of 16 has just got a job delivering at $14 a week.

Big Polish peasant mother, nursing her ninth unconcernedly. “When I bring home $20, my wife say, ‘big pay this week’,” says the husband. Six weeks layoff from the wash house before the strike and a boy in the hospital. “What we gonna do?” he says. “Worker gotta fight — all strike together.”

Old Italian mother: drudging years have left her still keen and bold, old world gold and torquoise earrings swinging as she mocks fiercely at the cops. She mimics, in the jail cell as we wait, how they beat her. She warms my cold hands between her own. “Good bye, missus,” I manage to stammer when they let me out of jail, and she, the old fierce mother was left behind…

LESSONS OF PASSAIC by Norman Thomas.

AS one who had almost come to believe that the American people, including some parts of the American labor movement, were beyond caring what happened with regard to public questions, I have been encouraged by the interest aroused by the Passaic strike, especially in its civil liberties aspects. Here I should like to say a good word for the A.F. of L. Individual unions and individual unionists have supported the strike liberally. President Green has issued the most clear-cut statement I ever read from any A.F. of L. official denouncing the wrongs of strikers not yet connected with the A.F. of L. This holds out some hope for the future. Perhaps the labor unions will now tackle more vigourously the job of organizing the unorganized textile workers which is essential to further progress. Indeed the final measure of the success or failure of the Passaic strike will be its contribution both to the determination to organize and the strategy of organizing the unorganized wage slaves who form so large a part of America’s labor army.

The Passaic strike will serve a doubly useful purpose if it impresses upon the workers one of the most flagrant evils of the capitalist system. I refer to the concealment of profits by stock dividends and the capitalization not of the savings of investors but of the legal right to exploit both consumers and wage workers. The whole woolen industry has been the greedy beneficiary of a subsidy that all of us have helped to pay by reason of tariff rates. (And yet they have the nerve to call us outsiders when we begin to inquire into the nature of the industry we have subsidized!) The industry pays tragically low wages and expects the brunt of industrial depression to be borne by these underpaid workers. Yet in its years of prosperity the Botany mills alone increased their stock from 34,000 to 497,000 shares by a clever process of reorganizing the industry and dividing up its past surplus. It is on this swollen capitalization that the bosses seek to pay profits wrung from the workers. A contemplation of this basic fact may have greater educational value than the more colorful incidents of the strike which I have omitted. Anyway, here’s to the strike and the ultimate victory!

The New Masses was the continuation of Workers Monthly which began publishing in 1924 as a merger of the ‘Liberator’, the Trade Union Educational League magazine ‘Labor Herald’, and Friends of Soviet Russia’s monthly ‘Soviet Russia Pictorial’ as an explicitly Communist Party publication, but drawing in a wide range of contributors and sympathizers. In 1927 Workers Monthly ceased and The New Masses began. A major left cultural magazine of the late 1920s to early 1940s, the early editors of The New Masses included Hugo Gellert, John F. Sloan, Max Eastman, Mike Gold, and Joseph Freeman. Writers included William Carlos Williams, Theodore Dreiser, John Dos Passos, Upton Sinclair, Richard Wright, Ralph Ellison, Dorothy Parker, Dorothy Day, John Breecher, Langston Hughes, Eugene O’Neill, Rex Stout and Ernest Hemingway, Artists included Hugo Gellert, Stuart Davis, Boardman Robinson, Wanda Gag, William Gropper and Otto Soglow. Over time, the New Masses became narrower politically and more journalistic in its tone.

PDF of full issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/usa/pubs/new-masses/1926/v01n02-jun-1926-New-Masses-2nd-rev.pdf