‘The Significance of the Sit-Down Strike’ by William Z. Foster from The Communist. Vol. 16 No. 4. April, 1937.

THE victory of the auto workers in their recent big struggle against General Motors definitely established the sit-down strike as a powerful weapon in the armory of the working class. In other countries there have been in past years many examples and varieties of the sit-down and stay-in strike. Among them was the famous strike of the Italian metal workers in 1920, when the workers occupied practically the entire metal industry. There have been also various stay-in strikes in China, Japan, Poland, and other countries, and, of course, the huge wave of sit-down strikes in France in the summer of 1936.

Nor has the United States been without early examples of this form of strike now so popular. Most famous of all such cases was the seizure of the steel plants of Homestead, Pennsylvania, by armed workers during their fierce struggle in 1892. Shortly afterward the metal miners in Telluride, Colorado, also occupied the mines in their neighborhood and engaged the troops in pitched battle. In following years there were also more or less rudimentary forms of the stay-in strike to be found in the tactics of the I.W.W., and it used to be the practice of the Chicago packinghouse workers, members of the Butcher Workmen’s Union prior to 1904, to sit down and bring production to a standstill during the time when the business agents were in the respective departments adjusting grievances. These sit-downs, or stoppages as they were called, were very effective in speeding up the bosses to make satisfactory settlements of the grievances in question. There were, moreover, early traces of the sit-down strike in the auto and various other industries.

But why has the sit-down strike suddenly become so widespread with the workers? Obviously it is not because some inventive worker has suddenly discovered this form of strike. The explanation is not so simple. The real reason is to be found in a whole complex of circumstances and developments which have now come to a head. Behind the eager grasping of the workers at the sit-down strike is a long story of the growth of giant monopolies, of intensified exploitation of the workers and of complete defeat of all attempts of the workers to secure redress of their grievances through the traditional craft unions, with their haphazard organizing campaigns, one-horse strikes, and milk-and-water policies. Fierce exploitation, brutal repression, speed-up, low wages, unemployment, etc., have in recent years made the workers more and more militant, particularly in such high speed industries as rubber and auto, and made them ready for action. So that when the occasion presented itself they seized upon the method of the sit-down strike, with the results we have seen. The organization of the mass production industries produces not only the new organizational structure, industrial unionism; but also a new strategy, the sit-down strike.

The decisive factor in releasing the mounting discontent of the workers into the special form of the sit-down strike is political in character. The workers, together with other toiling masses, succeeded in administering election defeats to the great capitalist interests; first, in the rejection of Hoover in 1932 and especially in the defeat of Landon in 1936. These victories gave the workers a new confidence and sense of political power. It is significant that almost immediately after the inauguration of Roosevelt in 1933 a great wave of strikes began to get under way, and it was not long until, among these struggles, the sit-down strike began to make its appearance in the packing (1933), the rubber (1934) and other industries. This strike movement, including the sit-down aspects of it, was the workers’ registering of their growing feeling of strength, particularly their newly realized political power.

Far more than following the 1932 elections, the workers felt a strong sense of political power after the defeat of Landon in 1936. The issue had been more clearly drawn in the 1936 elections; the class line-up was much sharper. So, naturally, when the workers, farmers and petty-bourgeois masses dealt such a heavy blow to the united forces of Wall Street, they became infused with a strong sense of victory. As never before they felt that they had a stake in the government. Many in a large measure came to look upon the Roosevelt government as their friend. Concretely, they did not believe that this administration would use the usual methods of terrorism against them to buck their strikes. Thus the groundwork was laid for more advanced forms of economic and political struggle. The whole fight advanced to a higher plane. A wide development of the sit-down strike was one result. Especially has the sit-down strike tendency grown after the inability of the employers effectively to use the armed forces of the state against the auto sit-down strikers.

It is significant that the Italian seizure of the plants in 1920 took place after great political victories by the workers, at a time when the capitalist government was paralyzed and the army and police could not be used by the capitalists against the workers, and also that the great wave of strikes in France developed immediately following the great success of the Popular Front. The victory of the French sit-down strikers was not without its repercussions in this country; but in the first instance, the development of the sit-down strike in the United States is a major sign of the awakening political consciousness of the American working class. It is a basic indication of the politicalization of the workers’ struggles.

In the auto strike the workers did not carry out the occupation of the factories in a revolutionary sense. They did not, in the mass, consider their sit-down holding of the plants as a forecast of the eventual revolutionary expropriation of the automobile kings. Instead, they conceived of the sit-down strike only as a very effective means to accomplish their immediate demands of union recognition, wage increases, etc. Nevertheless, the auto sit-down strike constituted a much sharper challenge to bourgeois property rights and capitalist state domination than does the usual type of strike. It was also a far more significant assertion of the workers’ right to their jobs and to control over the machines and factories. The auto workers’ bold “trespass” on company property, their flouting of repeated court injunctions, their militant repulse of police attacks, etc., all required a much higher militancy and more developed class feeling than does the ordinary walk-out. And by the same token, the strikers’ dramatization of these advanced class qualities in the strike served as a real object lesson and stimulant to evoke corresponding higher class sentiments among the great masses of workers in other industries. The auto sit-down strike marks an important stage in the developing class spirit and mass movement of the American workers. It was a significant lesson in their revolutionary education.

The effectiveness of the new sit-down strike was made so clear in the auto situation that all the world could recognize it. Small wonder then that the General Motors strike was followed by sporadic outbursts of sit-down strikes all over the country. The United Automobile Workers of America, a new, weak, and undisciplined union, containing in its ranks only a fraction of the employees of the General Motors Corporation, was able, by its sit-down policy, completely to paralyze the whole General Motors production and to force this giant corporation to swallow its own previous warlike, open shop declarations and to grant union recognition. This was a major victory, a blow in the face to great trustified capital generally.

In his article in the March issue of The Communist, W.W. Weinstone, Communist Party Secretary in Michigan, gives a valuable analysis of the special advantages of the sit-down over the walk-out and shows how the new method achieved victory. It is not my purpose to dwell here upon this phase, beyond saying that through their actual sit-down occupation of the factories the auto workers were able to checkmate three of the greatest strikebreaking weapons of the employers: the scabs, the courts and the police. Hence, success was theirs. All told, of the 150,000 workers made idle by the strike, only some 50,000 were actual strikers, and of these much fewer were actual sit-downers. Had it been a regular walk-out (instead of a sit-down) involving as it did only one-third of the workers, the winning of this strike would have been much more difficult, what with the strikers more exposed to strike-breaking, police attacks, court injunctions, etc.

Can the new sit-down strike be used in all industries, or is its application restricted, for technical reasons, only to certain industries? An answer to this question is to be found in the widespread use the workers are now making of the sit-down in many industries as diverse as watch-making, steel plants, building service, printing, coal mining, shoe-making, department stores, restaurants and automobile production. It may be safely concluded that the sit-down strike is applicable to all, or nearly all industries. But it cannot be applied mechanically and in blue-print fashion everywhere. The forms and methods of the sit-down strike will vary from industry to industry according to the specific conditions, even as does the walk-out. The walk-out strike of the coal miners, for example, is industrial in character and usually national in scope, and it differs radically from, say, the characteristic local craft strike in the building trades. And from place to place and industry to industry the sit-down strike will show similar variety in its application.

Manifestly, certain industries are more vulnerable to the sit-down strike than others. It seems clear that, from a technical standpoint, the highly strategic public service industries, such as railroads, telegraph, post office, electricity, telephone, radio, etc., are highly sensitive to this form of strike. In general, also, the fabricating industries, those turning out highly specialized products for the market under mass production conditions, will prove more vulnerable to the sit-down than are the basic industries producing raw or semifinished materials. Thus the automobile industry is more sensitive than steel.

Consider General Motors for example: It is made up of a group of greatly specialized plants, all fitting together like cogs in one machine to produce a few very individual types of automobile. Put a few parts of this delicately adjusted mechanism definitely out of action by a firm sit-down strike backed by mass support and the whole machine is disrupted and paralyzed. But take, say, the United States Steel Corporation, and it is quite a different matter. This concern’s major products—rails, sheets, tubes, plates, wire, etc., are much more of a general character and much less individualized. The process producing them is made up of a chain of separate mills making the same commodity, rather than one integrated mechanism as in the auto industry. Hence, were United States Steel production to be stopped by a sit-down strike at a given strategic point, it would be a much easier matter to transfer the affected production to another mill or even to another company than it is in the case of the highly specialized, individualized and integrated products of the General Motors Corporation. The same principle applies in various degrees to the production of coal, lumber, and many other raw and semi-finished materials. Another elementary factor making the sit-down strike more effective in fabricating plants is the threat of a boycott that such a strike precipitates in these industries. Under present conditions United States Steel would have nothing to fear in the shape of a mass boycott of its rails, plates, tubes, etc., in case it violently suppressed a sit-down strike. But it would be quite another matter with the General Motors or other manufacturing companies which have to sell their popular-priced products to the general public. What, for example, would have happened. to the reputation of the cheap Chevrolet car if the Flint strike had been drowned in the workers’ blood? More or less of a boycott would surely have developed against it. During their recent strike, fear of such a boycott, no doubt, was much in the minds of the General Motors chiefs (particularly in view of the strong competition in the automobile industry). But the steel barons would hardly need to give the boycott a thought in attempting to violently crush a sit-down strike in their industry.

The conclusion to be drawn from all this is not that the sit-down strike is inapplicable to the basic industries, but that in these industries it must take on special forms. In such basic industries, the sit-down strike, with less sensitive key spots to hit, will tend to take on necessarily more of a broad mass character than in the fabricating industries. It will also probably display more dramatic and militant features.

Does the sit-down strike render the traditional walk-out strike obsolete, as some are now saying? The answer to this is, no! On the contrary, the sit-down should be considered as an extension, a development of the walk-out. Where it can be used, the sit-down is a sort of front-line trench of the walkout, a salient drive into the line of the enemy. And as it ordinarily constitutes a very exposed salient facing the heaviest fire from all the forces of the employers, it must necessarily be supported by the organization and strategy of the mass walk-out. Inasmuch, as in war, there is always a grave danger of the sit-down strike salient being pinched off by the strong attack of the enemy, the workers must be prepared if necessary to meet this emergency by a strategic retreat instead of a disordered flight. In such a contingency, if the sit-down strikers are driven out of the plants by the violence of the employers and the state, care must be used so that this does not break the strike by having in readiness a solid line of defense to fall back upon: the picket lines around the plants.

Nor does the sit-down strike obviate the necessity of mass organization and struggle. In some quarters there is the thought that by use of the sit-down strike a bold and daring minority of workers, paralyzing a key point, can cripple a whole industry and thus make unnecessary strike action by the broad masses of workers in the industry as a whole. But this is a grave error, and if persisted in is bound to lead the workers to costly defeats. The reality is that just because of its very effectiveness (and hence the opposition it provokes from the class enemy) the sit-down strike requires the support of mass organization in the highest measure. Just as in military war a salient driven into enemy territory has to be supported with all available resources, so does the sit-down strike require the solid backing of labor’s heavy forces. We must avoid falling into a new form of the craft union illusion that strikes in basic industries can be won simply by the action of small bodies of strategically placed workers: in the one instance by strikes of skilled mechanics, or, in this case, by crippling key industrial points by small sit-down strikes.

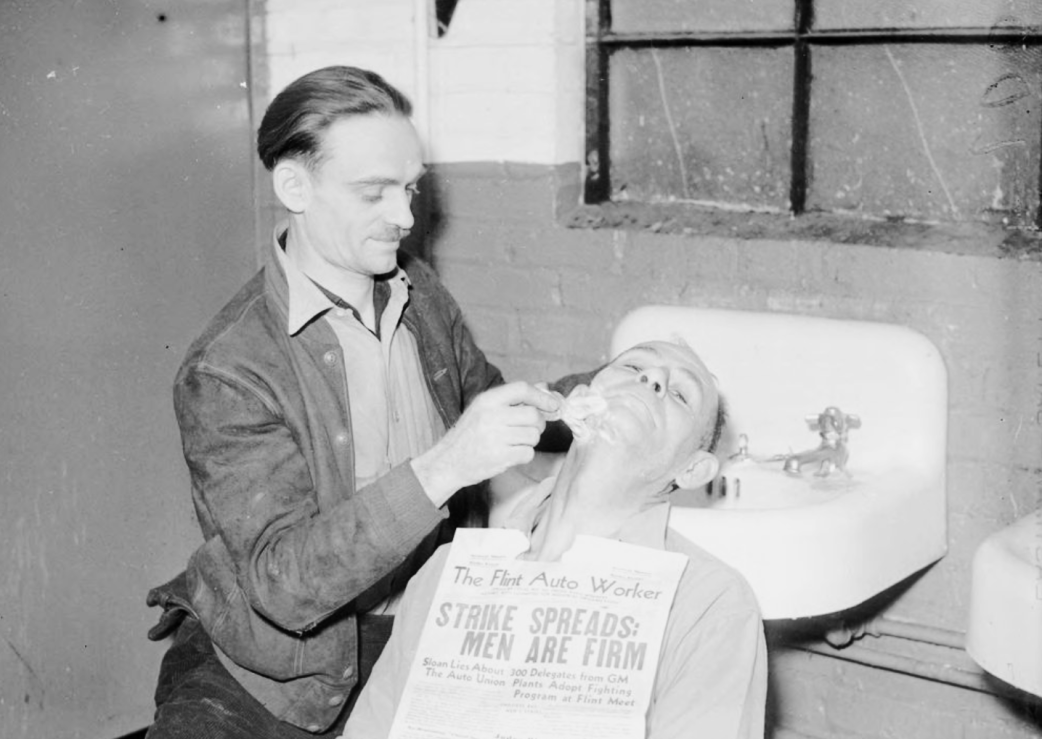

To carry through the sit-down strike effectively requires higher, not lower, forms of mass organization. To begin with, those portions of the workers that actually occupy given plants, even if they constitute a minority of all strikers, must themselves have a most elaborate organization and discipline. This must cover problems not only of feeding, sleeping, education, picketing, entertainment, but also very active measures of defense against attacking forces of police and gunmen. And, besides this, the sit-down must be backed up by the masses outside the sit-down plants with picket lines, demonstrations, relief and defense, and publicity work, etc., to keep the rest of the industry closed down, to prevent the influx of scabs, to mobilize public opinion, etc. Moreover, the carrying through of the sit-down strike raises the issues of working class political organization and struggle in very sharp form, the success of the sit-down strategy depending so much as it does upon the issue of who controls the local and state government forces and hence, whether or not they can be used violently to eject the sit-downers from the plants. The sit-down strike movement thus places still sharper the question of organizing the Farmer-Labor Party and the broad People’s Front.

The sit-down strike must be used as a stimulant to create mass working class organization and struggle on both economic and political fields and not as a substitute for it. It is true that up till now the sit-downers have won rather easy victories in most cases. But this is due to the fortunate combination of the rising militancy of the workers, the increasingly favorable industrial situation, the evident confusion of the employers in the face of the new sit-down strategy, and their inability so far to use the state forces effectively against the unions. But we may be sure that when the employers dig themselves in and really begin to fight the sit-down strike, that its successful application, precisely because of its paralyzing power, will require a higher degree of consciousness and organization by the workers than the traditional walk-out. The very weakest phase of the Flint sit-down strike (and the thing that at times seriously threatened its defeat) was exactly the fact that the sit-downers were not actively supported by a strongly organized majority of the automobile workers.

The sit-down strike is a splendid means of developing trade union organization and raising the political consciousness of the workers. This has already been amply demonstrated by the experience to date. And precisely because of this fact, we can be sure that the employers will use every means at their disposal to knock this new and powerful weapon from the hands of the workers. We have seen how long and hard they have fought against the workers’ right to the walk-out strike, and we must be prepared for the bitter struggle they will make against the workers’ use of the still more dangerous sit-down strike.

Already as I write this the capitalists and their allies, deeply alarmed over the outcome of the General Motors’ strike, are beginning to go aggressively into action against the sit-down strikers. Typical of their attitude are Governor Hoffman’s threats of violence and bloodshed against the C.I.O. Oceans of hostile propaganda against the sit-down strike; sweeping injunctions, mass arrests and tear gas attacks against the sit-downers; legislation to outlaw the sit-down strike as trespass and illegal seizure of property; reorganization and fortification of industrial plants, and various other forms of attack and defense, indicate the vigorous resistance that the employers are going to make to prevent the establishment of the sit-down strike as a recognized method of working class struggle.

This anti-sit-down strike campaign dovetails into the efforts of the employers generally to kill the growing militancy of the trade union movement. Fearing that the C.I.O.’s campaign to organize the mass production industries will succeed, and alarmed at the prospects that they will have to face a much more strongly entrenched and aggressive labor movement, the employers through their organizations generally are definitely aiming at hamstringing this future militant movement by trying to inflict upon it such spirit-destroying devices as compulsory arbitration, state incorporation of unions, etc. Such was the strategy used by the British employers after the general strike of 1926, and this was also the means employed by the American railroad barons to take the punch out of our railroad unions after the big national strike of the railroad shopmen in 1922. To destroy the militancy of the trade union movement is the purpose of the flood of articles now to be found in the capitalist press about the blessings of a “strikeless England” and the methods used to bring this condition about.

All this thrusts upon the workers the necessity of a stern fight to establish the practice of their sit-down strike. The way for the masses to do this is to apply the sit-down on the widest possible basis. Especially is the fullest advantage to be taken of the present favorable conditions; the workers’ militancy and sense of victory, the improved industrial production, the advantageous political situation and the partly defensive position of the employers. To legalize the sit-down strike the workers must sit down far and wide in industry, backing up this action with the necessary economic and political measures indicated above.

The C.I.O. should give all encouragement to the sit-down strike movement, because it has shown itself to be a powerful stimulator to the organization of the unorganized. As for the A.F. of L. officialdom, it is clearly a barrier to the movement. The A.F. of L. leaders, characteristically fearful of all rank-and-file militancy, and true to their instinct as capitalist toadies, have already condemned the sit-down strike; first by John P. Frey’s open denunciation of it as a device of Moscow, and later by William Green’s hypocritical move to “study” the whole question. Nor can the Roosevelt government and its branches in the various states and cities be depended upon to sustain or even tolerate sit-down strikes. President Roosevelt and Governor Murphy of Michigan wobbled very badly on the auto strike, and the workers managed to stick in the Flint plant only in the face of much adverse pressure from both the state and national governments. It was chiefly the fear of a serious discrediting of the whole Roosevelt regime that prevented Governor Murphy from ousting the sit-downers by force.

The Communist Party should, of course, lend every assistance to the sit-down movement, both by practical organizational measures and political guidance. The Party must make the question of organizing the unorganized its main mass slogan. It should mobilize all its forces in the national unions, local lodges, and central trades councils to stimulate organization work on every front and in every industry. In the various organization campaigns the Communist Party should urge the adoption of the sit-down strike wherever practicable, being careful to see that this form of strike is used in a disciplined manner, that it is supported by a solid mass movement of the workers generally in the given industry and that it is followed up by persistent campaigns of trade union organization. The Party should also strike to induce the A.F. of L. craft unions to use the sit-down strike, and it must make use of the growing strike sentiment generally to strengthen unity tendencies between the A.F. of L. and the C.I.O. and defeat the latest splitting tactics of Green and Frey. And without fail, the Party must make clear to the workers the full political implications of the sit-down strike, and utilize the growing consciousness of the workers to further the formation of the Farmer-Labor Party.

The sit-down strike movement is giving a great stimulus to trade union organization and to the political organization of the working class. It is infusing the masses with fresh hope, inspiration and fighting spirit. It is enabling them to deal heavy and successful blows at their worst enemies, the great trusts. The task of the Communist Party, therefore, is to develop this powerful weapon of the sit-down strike to its maximum possibilities. The sit-down strike will be, in the next period, one of the major dividing issues between the forces of progress and reaction in the United States.

PDF of original issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/usa/pubs/communist/v16n04-apr-1937-The-Communist.pdf