Editor of ‘Irish Workers Voice’ and leading member of the newly formed Communist Party of Ireland brings his anti-imperialist perspective to this critique of Robert Flaherty’s film ‘Man of Aran.’

‘Flaherty’s ‘Man of Aran’’ by Brian O’Neil from New Masses. Vol. 13 No. 5. October 30, 1934.

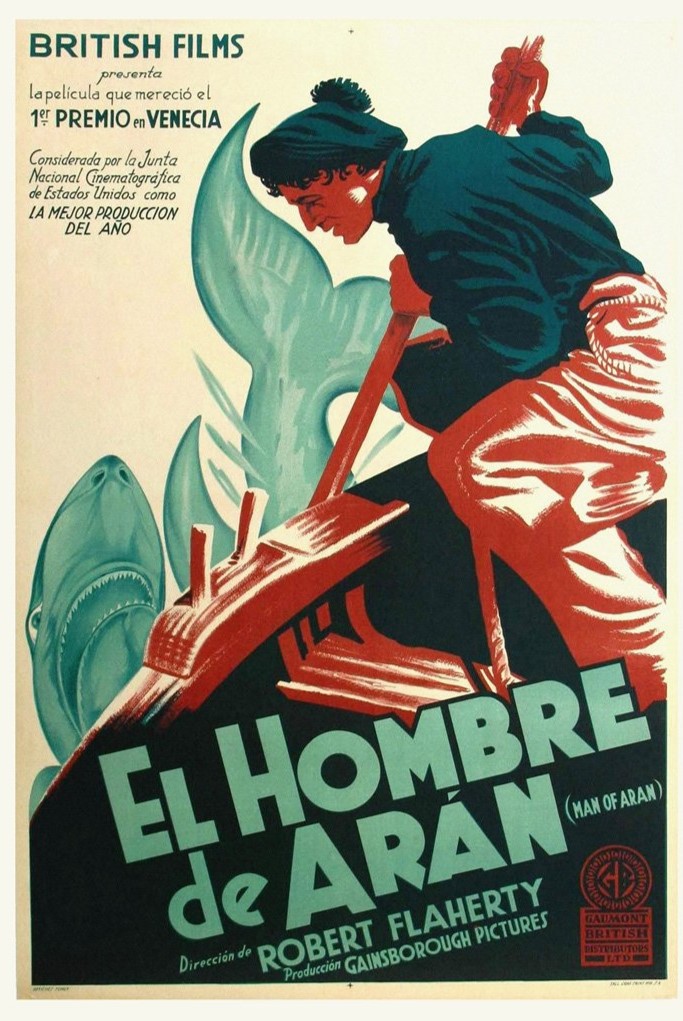

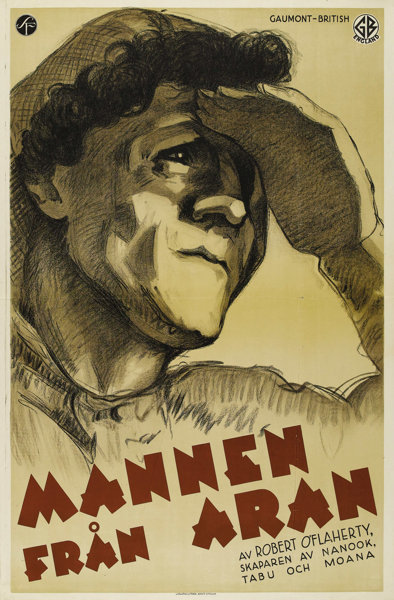

ROBERT FLAHERTY’S new film, Man of Aran [Criterion] has evoked the unanimous adulation of the bourgeois critics in Europe. Few films have been so praised. To a Marxist the reasons are quite clear. Here is a film to which the cultured bourgeoisie, ashamed of the productions of Hollywood, can give the cachet of a “work of art,” yet a film patently in accord with the prevailing ideology of the capitalist class, and, unlike the indubitable screen masterpieces of the Soviet Union, not in the least dangerous socially. Man of Aran (British Gaumont) shows that harshness, strength and struggle can yet be distilled into a pastoral; that Robert Flaherty, for all that “realism” which bourgeois critics see in him, remains one of Zola’s “impenitent romantiques,” ever in quest of Arcadia.

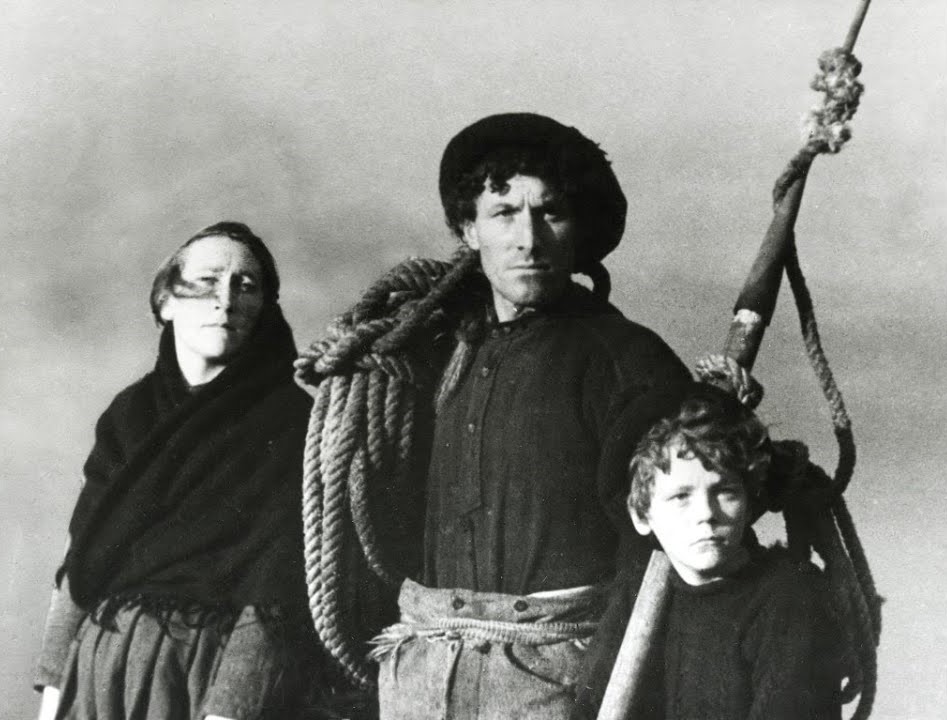

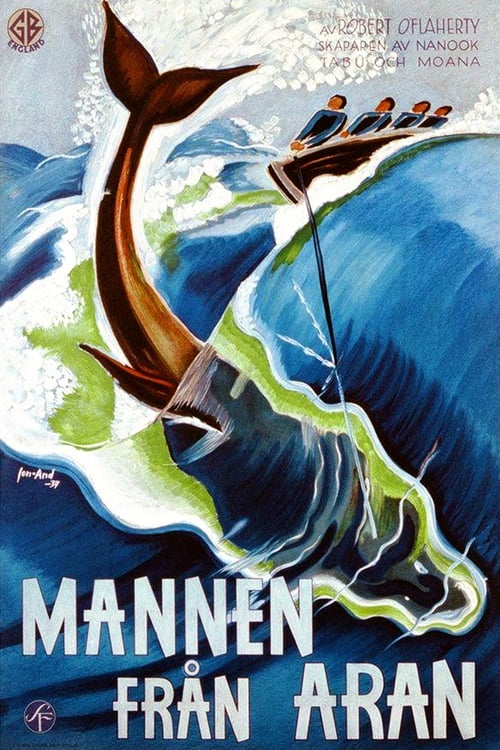

Off the west coast of Ireland are the three islands of Aran-Inishmore, Inishmaan and Inishere. For two years Flaherty worked here, making friends with the people, selecting his cast from them instead of using professional actors, and the result is his new film. There is little story in Man of Aran. Tiger King and Maggie Dirrane are man and wife; little Michaeleen is their son. Only this one family comes within the range of the camera lens, save for glimpses of Patch Ruadh (Red Beard), the old seanchaidhe (story-teller) and of the boat crews putting out from the shore. We see Tiger King caulking his boat or breaking the rock to lay his hand-made farm, Maggie Dirrane collecting soil in a basket from the crevices of the rocks or dragging sodden seaweed from the shore, Michaeleen helping where he can or fishing from the top of a cliff. The climax is the battle of Tiger King and his curragh (canvas boat) crew to capture a huge shark in order to boil down its liver and have lamp-oil for the winter nights.

There is a deal of powerful photography. Unquestionably Flaherty is a superb cameraman. The surge and swirl of the sea; the battering of the great breakers against the island so that the spume licks up scores of feet to the anxious watchers on the cliff top; the virility of Tiger King and the madonna-like features of Maggie Dirrane–these are limned in magnificent shots. But Flaherty’s technical dexterity only underlines the basic falsity of the film.

In what does this falsity consist? In this: in Flaherty’s deliberate portrayal of the islanders as primitives, twentieth century Neanderthals, cut off from all social relations, aloof from the social forces of modern capitalist society, and with Nature as their only enemy. In actuality, the Aran people are as closely bound to capitalism and its problems as the Dublin or Belfast proletarians.

Why are the Aranmen pent-up on their rocky islands? Because British imperialism has laid waste the Irish countryside and given it over to bullocks and sheep; because capitalism holds the land from the Irish country people. The Aran folk were not exempt from the historic land struggles in Ireland. They came, hundreds of them in their curraghs, to answer the call for help of the Connemara peasantry, during the famous “Battle of Curraroe” in the Land League days. In later times they met evicting bailiffs and police with rocks and boulders and drove them back over the cliffs. And all through the decades, imperialist-made (i.e., socially-created, not primitive) hunger has exiled the youngsters to America.

Flaherty can be excused for avoiding these memories, this historical background. A more important thing is his conscious anachronisms. In the film, the men fish for sharks and the impression is given that shark-fishing is their ordinary occupation. Aranmen do not hunt sharks at all! It is herring and mackerel that they fish for, and their catches are sold on the mainland. In other words, their life is a constant market relation. And the collapse of market prices of fish, together with the inability of their out-of-date curraghs to compete against the French and Scottish steam trawlers that fish the Irish waters, is making their livelihood more and more hazardous.

It is many years since Aranmen sought sharks’ livers for lamp-oil. Today they buy kerosene from the mainland. Again, Carlyle’s “cash nexus.” (There is even a malicious rumor that Flaherty had to teach the islanders how to use the harpoon; they had forgotten the art.)

Flaherty’s Man of Aran is a Robinson Crusoe. He and his family stand alone on the island skyline. We gather that he has no relations with human kind even on the island. This is a travesty of reality. lnishmore itself has a population of some 2,500 and possesses a public house; there are over 3,000 persons on the three islands. A steamer calls regularly. The people have to buy things; they have to pay rates to the Galway local authorities for the upkeep of roads, the county mental asylum, etc. They have ceilidthe (dances and sing-songs); they discuss politics and the world with degrees of sharpness; they go to mass; the priest takes his tithe from them and strives to keep their minds captive. But of all this, of the warm human relationships that are the outstanding feature of island life, there is no hint in Flaherty’s film. In short, he has portrayed not the real Man of Aran, but the Robinson Crusoe of his own creation, as much the product of the studio as if Tiger King lived normally in a palace on Beverley Hill.

Petit bourgeois critics are enamoured of this “realistic study” of “primitive life,” where economic crisis, class struggle and other bothersome phenomena are not. The Marxian critic will not blame Flaherty for fleeing to the edge of the world in order to escape capitalism. He will indict him, however, for pretending that he has succeeded, or can succeed in this Quixotism. And that is what he does in Man of Aran, a celluloid peer of the literary navel-contemplations that are now being penned by world-weary Montparnassians, whose impeccable style, or even word-genius, no one will deny.

It is a continuation of his earlier films, Nanook and Moana. In Moana he went to the South Seas to paint an idyl devoid of the booze, bibles, slave-labor and syphilis of the trader and missionary. But workers forgave the self-deception, recognized his genius and looked for something better next time. Because of this Man of Aran is all the more disappointing. Instead of advance there is retreat to “pure documentation” that is not even veracious; instead of his camera moving towards the wide sweep of a Pudovkin or an Eisenstein, it develops even more acute myo- p1a. It is not, of course, that Flaherty fails thus deliberately; the core of the failure is that he is still content to attempt to produce “things of beauty” within the bounds set by the celluloid kings. He does not see that there is no good whelp from a bad bitch; that only the smothering of his ability can result. Yet it is because of the incorrectness of his approach to it, his refusal to portray a “story,” that Man of Aran is almost completely lacking in dynamic power, that it has even agonizingly static moments, despite the brilliant patches already described.

It is stated that Flaherty intends to visit the Soviet Union. He will see them there making films of places and peoples much further from the world’s track than Aran, yet glowing with the stuff and blood of life. It is to be hoped that the experience will teach him to avoid his past errors, for he could be a fellow-traveler of standing and worth.

The New Masses was the continuation of Workers Monthly which began publishing in 1924 as a merger of the ‘Liberator’, the Trade Union Educational League magazine ‘Labor Herald’, and Friends of Soviet Russia’s monthly ‘Soviet Russia Pictorial’ as an explicitly Communist Party publication, but drawing in a wide range of contributors and sympathizers. In 1927 Workers Monthly ceased and The New Masses began. A major left cultural magazine of the late 1920s to early 1940s, the early editors of The New Masses included Hugo Gellert, John F. Sloan, Max Eastman, Mike Gold, and Joseph Freeman. Writers included William Carlos Williams, Theodore Dreiser, John Dos Passos, Upton Sinclair, Richard Wright, Ralph Ellison, Dorothy Parker, Dorothy Day, John Breecher, Langston Hughes, Eugene O’Neill, Rex Stout and Ernest Hemingway, Artists included Hugo Gellert, Stuart Davis, Boardman Robinson, Wanda Gag, William Gropper and Otto Soglow. Over time, the New Masses became narrower politically and more journalistic in its tone.

PDF of full issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/usa/pubs/new-masses/1934/v13n05-oct-30-1934-NM.pdf