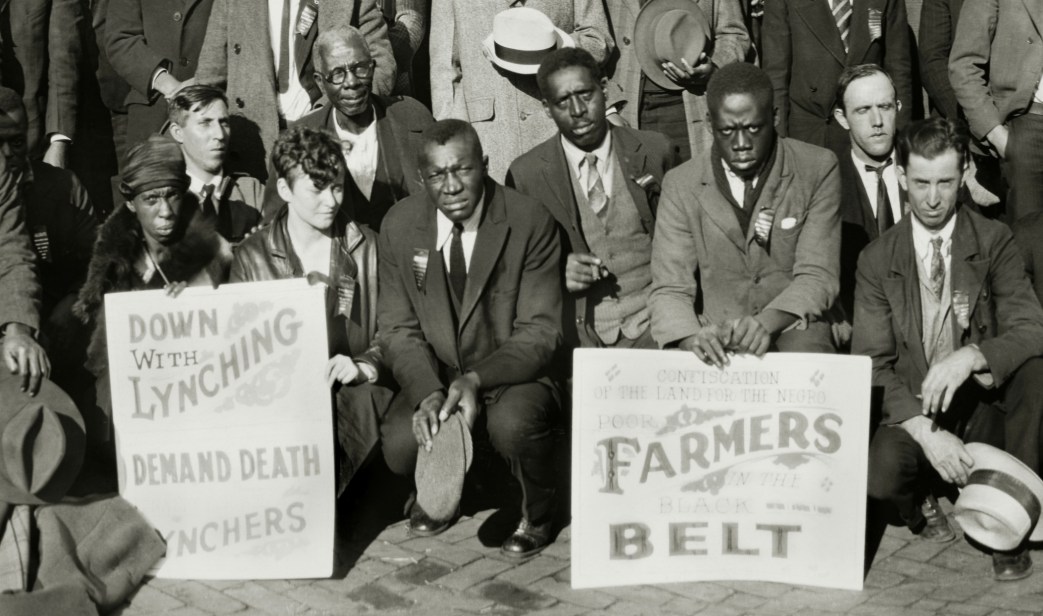

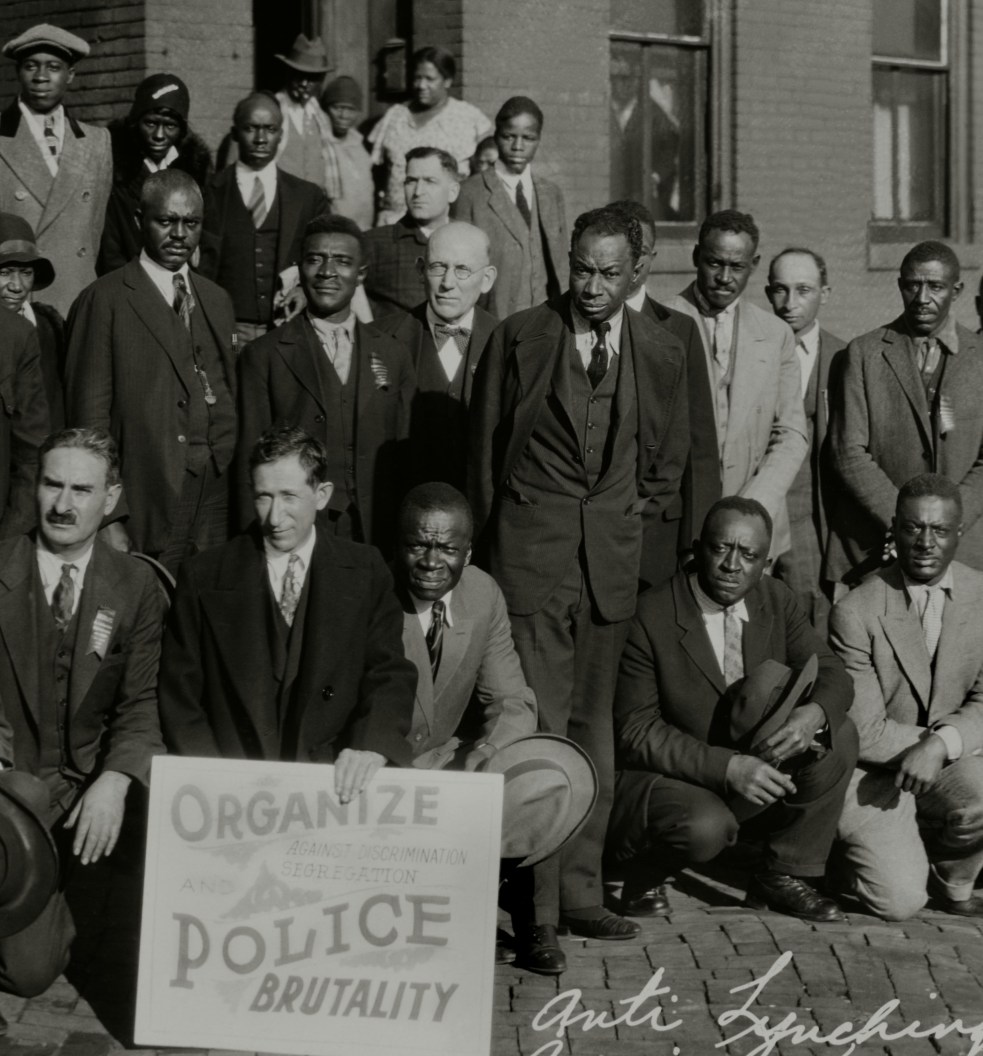

Cyril V. Briggs reports on some of the delegates who attended the Emergency National Convention Against Lynching in St. Louis during November, 1930. Over 100 delegates who attended founded the League of Struggle for Negro Rights. Illustrated with a remarkably detailed photo from the convention of those delegates. How I wish I knew each one of their names and their stories.

‘Riding the Rods to St. Louis Convention’ by Cyril V. Briggs from the Daily Worker. Vol. 7 No. 286. November 29, 1930.

NO one who attended the St. Louis convention of the League of Struggle for Negro Rights and heard the determined speeches of rank and file delegates from the South and from other parts of the country can doubt the determination of the Negro masses for struggle or mistake the impatience and disgust with which they view the betrayals of their struggles by such treacherous organizations as the N.A.A.C.P. and Urban League. Such is the present spirit of the Negro masses that several of the delegates at the St. Louis convention “rode the rod” to get to it. Eighteen year old Joseph Burton rode freight all the way from Birmingham to Chattanooga because he wanted to attend the Southern Anti-Lynching Conference and “join up in a real fight against lynching.”

Burton had learned of the League of Struggle for Negro Rights (at that time the American Negro Labor Congress) through a contact in the Birmingham Laundry in Birmingham, where with a number of other workers he slaved six days a week, 12 hours a day. As a wringer Burton got $2.25 a day—$13.50 a week. A pitiful wage for a worker whose parents had 11 children and himself the main support, for the others are now’ unemployed. He told the convention how Negro women and girls were driven 12 hours a day for 75 cents in the same plant, and how the workers were often robbed of a day’s wages through the bosses switching finished work to somebody else. claiming it had not been finished. Burton’s family of 13 lived in a 3 room shack, no gas, no electricity, no sanitary arrangements, outhouse in the yard. For this they paid $18 a month. Burton never attended school. He had to go to work at the age of ten. His father told him not to return home if he mixed with “the radicals who are fighting lynching.”

At Chattanooga he made the most militant speech of the southern conference and was elected a delegate to the St. Louis convention. He came to St. Louis with Mary Dalton and other white and Negro delegates from the south. Two days, two nights on the road in a car that insisted on breaking down; held up by police, threatened with jail on vagrancy charges, refused service in white restaurants, not always able to get to the Negro sections, starving, cold, uncomfortable, but never whimpering, the southern delegates forced their way to the convention, Negro and white suffering alike when the jim-crow restaurant? refused service to the Negro comrades, refusing them even the use of the comfort stations!

MARY Dalton told the convention of the enthusiasm of the southern workers, (white and colored) for the movement. How every delegate at the Chattanooga conference wanted to come to St. Louis to help carry on the fight; how the workers supported Bell, a Negro worker nominated on the Communist ticket for U. S. Senator, how in six Tennessee counties they gave Bell 640 votes, in spite of the wide spread stealing of the boss parties, how the boss press raved when Bell was nominated, and how the Communist Party is steadily breaking down the barriers of race prejudice and hatred built up by the imperialists to split the working class and weaken its struggles.

Ben Careathers of Pittsburgh spoke of unemployment in that city, of the misery and starvation of both Negro and white workers, told of the coal and iron police breaking up meetings of the League of Struggle for Negro Rights. He told of the fighting spirit of the Negro miners and steel workers, of their determination to carry on against boss oppression.

Kingston of Philadelphia gave a detailed report of the experience of the League in that city, its efforts to work within the Garvey organization, its success in creating five functioning locals and a City Committee, its leadership of the every-day struggles of the Negro masses. Not all of the delegates were as clear upon the class nature of Negro oppression as were Kingston, Mary Pevey, Careathers, Mary Dalton and others. But one and all were aware of the need for organized struggle, of the need for unity between the black and white workers. Most of them realized the fundamental difference between the oppressing imperialist governments and the first workers republic, the Soviet Union. All lustily cheered as William Brown, a Negro steel worker of Detroit and returned delegate from the Fifth Congress of the Red International of Labor Unions, took the floor with the opening remark:

“I am just returned from a country where all men are equal regardless of color, creed or nationality. I bring to you the greetings from the workers of the Soviet Union.”

And they cheered again when Brown told of the expulsion from the Soviet Union of the two Americans who attacked a Negro worker in the Stalingrad Tractor plant. “Soviet Russia will not tolerate the ways of Bourgeois America,” Brown quoted the Soviet press, and the convention went wild with applause.

In every way the delegates and the organizations they represented showed their willingness for struggle, their recognition, in fact, of the vital need of organized militant struggle against the bosses lynching terror and oppression.

Like the race riots after the World War and during the crisis of 1921, the St. Louis convention of the League of Struggle for Negro Rights affords a sharp contrast between the militancy of the Negro masses, who are actually clamoring for courageous leadership in the struggle against their terrible conditions and frightful oppression at the hands of the white ruling class, and the bellycrawling exhibition of the Negro petty bourgeoisie (preachers, landlords, shop keepers, etc.) such as these misleaders are even now performing in a fake anti-lynching conference at Washington, D. C. under the leadership of the Equal Rights League of Boston.

JUST as during the riots, it was the Negro workers who met the boss inspired. boss-led mobs with guns in their hands and beat down the terror by grim notice to the mobs that Negroes were ready to defend themselves, so today it is again the Negro masses who give militant voice to their protests against the wrongs inflicted upon them by the imperialists of this country, against wage cuts, lay-offs, unemployment, mass starvation and misery. Just as during the riots, the so-called leaders from the petty Negro bourgeoisie betray the masses the Negro workers are mobilizing for militant struggle against the imperialists and are voicing their demands for the right of self-determination for state unity of the Black Belt, for confiscation of the land for the Negro workers who work the land as the only solution of lynching and Negro oppression.

The Daily Worker began in 1924 and was published in New York City by the Communist Party US and its predecessor organizations. Among the most long-lasting and important left publications in US history, it had a circulation of 35,000 at its peak. The Daily Worker came from The Ohio Socialist, published by the Left Wing-dominated Socialist Party of Ohio in Cleveland from 1917 to November 1919, when it became became The Toiler, paper of the Communist Labor Party. In December 1921 the above-ground Workers Party of America merged the Toiler with the paper Workers Council to found The Worker, which became The Daily Worker beginning January 13, 1924. National and City (New York and environs) editions exist

PDF of full issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/usa/pubs/dailyworker/1930/v07-n286-NY-nov-29-1930-DW-LOC.pdf