This excellent introduction to the difficulties facing organized labor in winning the auto industry, a struggle that took over forty years, by Robert W. Dunn also proposes a number of initiatives that would end up in the winning arsenal of the C.I.O. a decade later. Venerable left labor activist and analyst Dunn was the director of the Labor Research Association from its founding in 1927 until 1975.

‘Auto Workers Can Be Organized: A Plan of Action’ by Robert W. Dunn from Labor Age. Vol. 18 No. 4. April, 1929.

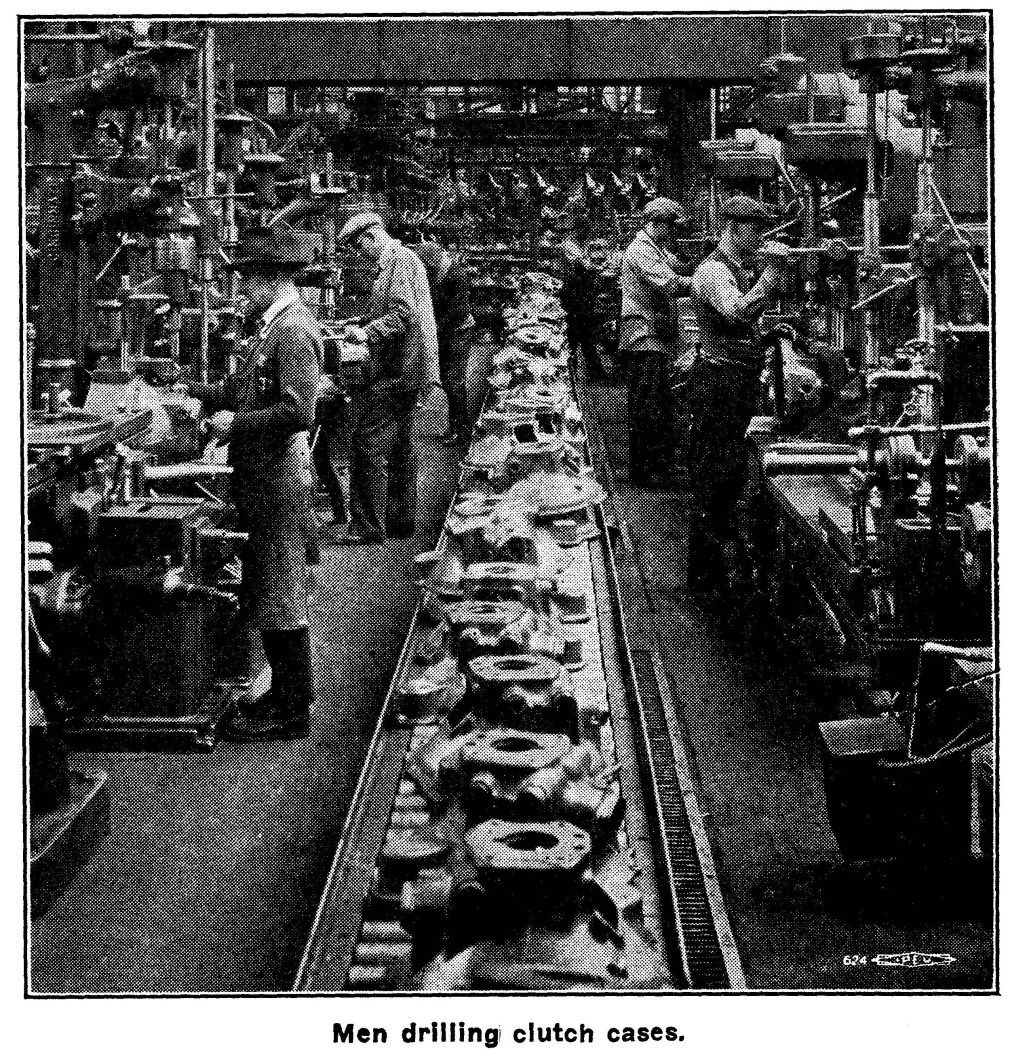

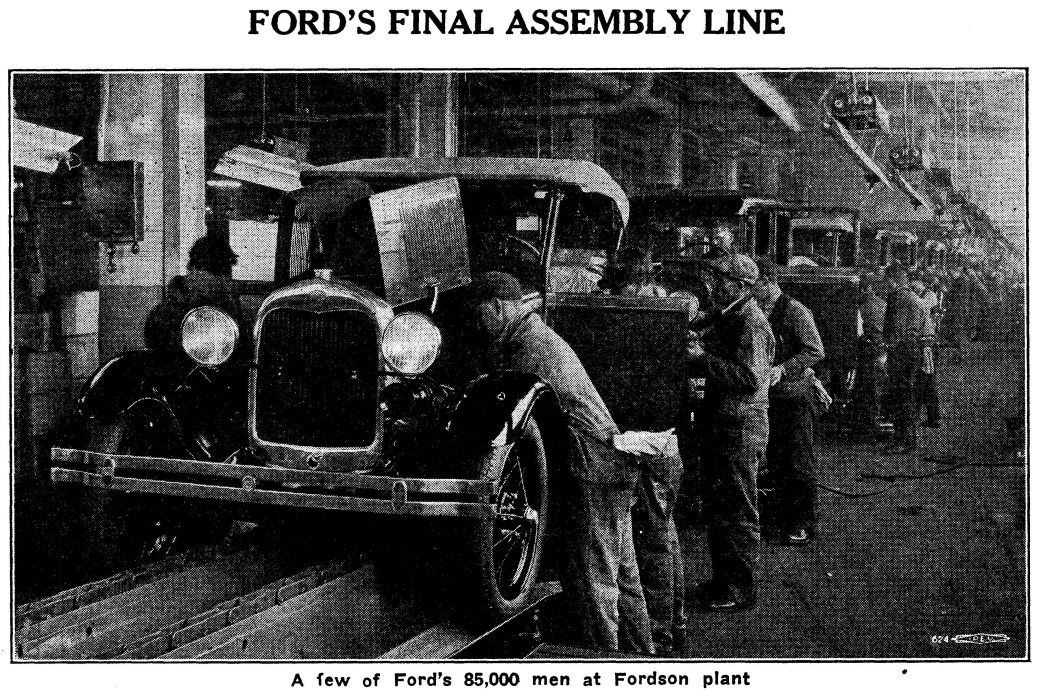

IN the automobile industry the workers are treated like mere cogs in a machine. They are handed arbitrary wage-cuts and lay-offs. Their hours of labor are excessive, and the speed-up is beyond endurance. A variety of “welfare” schemes deceive and intimidate them. Workers who dare to question the arbitrary decisions of foremen are fired. Under such conditions the need for unionization is self-evident.

Sufficient grievances exist for interesting, educating and arousing the men along the belt. Experiences gained in unions that have already functioned in the industry, and from the sporadic as well as organized strikes that have occurred, indicate the form, structure and procedure for the kind of union able to unite the various elements working in the plants.

The type of organization must be based on the structure of the automobile industry. It must be an industrial union, uniting the great mass of skilled and the minority of unskilled, regardless of age, color, sex or nationality. It must recognize the shop as the unit and carry on its propaganda by an appeal to the special grievances of workers in a particular department or plant, at the same time building a broad, effective defense against the Open Shop manoeuvers of the employers.

A brief review of the outstanding causes of discontent among the workers will indicate the more important demands which an auto workers union must put forward.

Demands

Wages of auto workers are below those required by minimum government budgets and also below those received by workers in unionized trades. The “high wages” in the industry are a myth. Although some workers fresh from farms and small towns may, at first, consider their wages comparatively high, they soon come to realize the higher cost of living in the auto centers and the drains upon health that the work entails. Higher wages will thus be among the first demands of auto workers. At present agitation for more pay should take the form of active resistance to the many wage cuts which are effected piecemeal and by a variety of methods.

This leads naturally to a consideration of speed-up, which the union would have to fight. The time-study device, the confusing bonus schemes, the driving of the workers, the group systems of payment — all have contributed to this harmful process. Without a collective voice in the plant the workers are bound to be driven harder and harder.

Hours are too long, averaging over 50 a week, and at certain seasons much longer. Overtime should be cut out completely and the available work spread over the year during normal working hours. And those normal hours should be — as an immediate goal — 40 a week. The 5 -day week and the 8-hour day, with a still shorter week in the more unhealthful departments, should be demanded.

Chronic Unemployment

Closely related to hours goes the whole question of unemployment. With auto production seasons determined more and more by style, and with the increasingly frequent introduction of new models, irregularities in employment multiply and unemployment becomes a chronic condition of the industry. Short-time work and lay-offs constantly menace the worker and reduce substantially his annual earnings. The shorter working week and working day would have some stabilizing effect on this situation. Realizing, however, that unemployment, — seasonal, cyclical and technological- — is an inevitable characteristic of the industry, as operated under the capitalist system, the auto workers must demand the enactment of legislation providing for the establishment of a system of federal employment exchanges and a comprehensive system of unemployment insurance.

Related social legislation should of course be worked for. In addition to unemployment insurance, the union would fight for state insurance covering old age, sickness, and accidents. Such measures, advocated by the union, would help to discredit the inadequate and paternalistic insurance used by several companies, such as General Motors and Studebaker, to tie the workers to their jobs and prevent organization. An effective union will also have to put up a vigorous fight against all the paralyzing stock ownership, company group insurance, and other specious welfare and personnel schemes.

But even before any such legislation is achieved the auto workers, in their first stages of organization, will be forced to fight defensively for the maintenance of certain elementary “democratic rights.” Free speech and assembly have been denied, and will repeatedly be denied, these workers by local politicians working under the thumb of the motor corporations. The workers will have to fight first for the right to meet, organize, strike and picket. They will have to fight the growing menace of the injunction. These general political demands will be uppermost at the outset of any unionizing campaign.

Political demands will, in turn, bring the auto workers face to face with the fact that both old-line political parties are the agents of the corporations. Out of their experience and struggles will develop a realization that only a Labor Party, representing the interests of the workers, can serve them in their struggle for industrial and political power.

Brutal Bosses

Then the workers must also demand some protection from the tyranny of the bulldozing foreman and sub-bosses. These slave-drivers are a part of the speedup system, the human agents facilitating its smooth operation. They can only be cured by a union. The workers as individuals are powerless against these little tsars. At the same time the workers, when properly organized, will not be so inclined as at present to blame all their troubles on these foremen. They will see that it is not the lower bosses, brutal though they may be, who are their main enemies, but the companies themselves. And they will see also that the struggle against the company is but a part of the class struggle against the millionaire owners of industries coining huge profits from their labors.

Dozens of minor grievances should, of course, be considered in framing a list of demands to be made by any automobile union.

The union that organizes automobile workers will also have to emphasize the special demands of young workers, women, Negroes, and foreign groups, all of them important factors in the industry. The enthusiastic support of youth is essential to any successful organization campaign. This can be gained by paying particular attention to their conditions. In the parts and accessory branches, and in those departments of all plants where women are prominent, their interests must be united with those of the men. Equal pay for equal work will be the initial demand, along with the strict enforcement of laws relating to the employment of women. The Negro, comprising 10 per cent of the personnel in some plants, and the foreign-born have often been discriminated against. These most exploited workers will respond to the call of the union that employs special organizers from their own groups to deal with their problems.

Having seen what the grievances and the demands of the workers are, we may draw a few conclusions as to the kind of union that can organize this completely non-union industry.

Power Through Union

In the first place it is evident that this industry will not be unionized without a struggle. To organize auto workers means fight. We know what the organized power of the employers is, their unceasing propaganda, their banking connections, their belligerent associations, their anti-union war chests, their readiness to use every weapon, subtle and brutal, to prevent workers’ organization — spies, blacklists, police power, injunctions, discrimination. It follows that a union seeking to appeal to the workers along the Belt will not talk “peace” and “cooperation,” but will have to sharpen its weapons for a long and difficult siege. Only a spectacular, sweeping campaign will finally break the absolute autocracy of the anti-union corporations It will not be done by sweet words inviting a few of the employers to a conference!

The Will to Fight

It is obvious that only a group with the will and the determination to organize can carry on such a fight. Labor leaders who declare that “the day of strikes is past,” will naturally accomplish nothing. Neither will those who exaggerate the obstacles apparent in the path of organization — the overwhelming financial resources of the corporations, the greenness, unskilled and transient character of automobile labor, the recurrent unemployment periods, the apparent inertia now prevailing. These are factors common to all large-scale trustified industry in America. They must be resolutely faced by an organization keenly aware of workers’ needs and possessing the will to fight.

In the third place, only a union that takes in every type of worker in the plant can do the job. Craft unions, built along customary A.F. of L. lines, have no relation to the problems arising in great plants full of unskilled machine tenders and one-operation specialists. Such unions, squabbling over jurisdiction, will only breed indecision and weakness, as they have in the past. The union that organizes auto workers must be a factory workers union. It must be as modern and up-to-date as the industry itself.

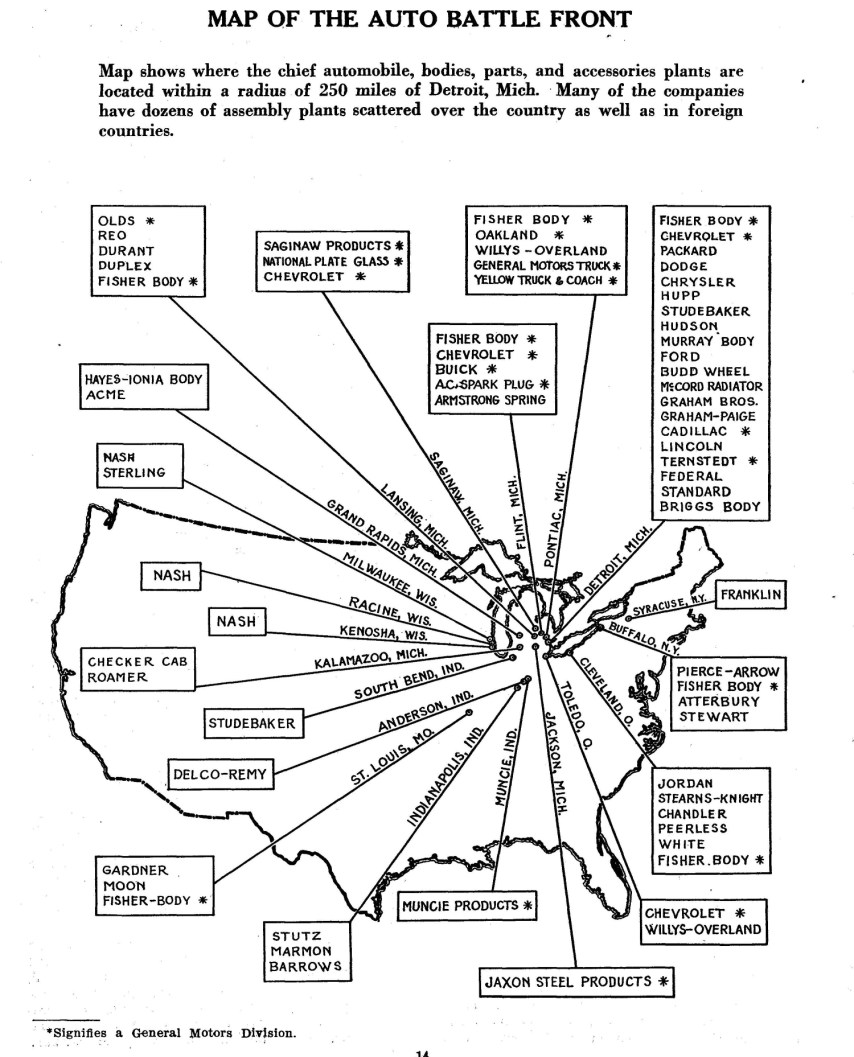

By the same token it must be a union covering the whole industry as well as every operation in the plant. General Motors, Ford, Chrysler and their associates have assembly plants dotting the country. All the associations of employing corporations are nationwide. Only broad-scale action concentrated at first in the main plants, but extended later to all the assembly units, can avail against such vast corporations. Fisher Body alone, with its 45 plants, calls for a union that stretches from, coast to coast,., that embraces the industry. And Fisher Body is but one division in the mammoth General Motors Corporation.

Federal Unions Inadequate

No federal labor union, affiliated directly to the A.F. of L., can organize these workers. It has been suggested by some that the Automobile, Aircraft and Vehicle Workers Union (usually known as the Auto Workers Union) disband its 6 locals, and that they should become Federal Labor Unions. This would mean: (1) the complete separation of one local of auto workers from another, rendering impossible the solidarity needed for struggles with employers whose interests and branches cover the country; (2) the control of funds by the A.F. of L. instead of by the local workers, leaving the latter without financial power, in addition to the denial of the right to call strikes without sanction from Washington; (3) the expulsion from the locals of the most active workers — the left wingers — as has happened in other federal locals; (4) the surrender of members to any A.F. of L. craft international at any time it chose to lay jurisdictional claims on them.

The division into Federal Labor Unions would thus stultify forever any efforts to organize the workers of the industry. The experience of General Motors workers at Oshawa, Ont., with a Federal Local after their strike in 1928 shows how ineffective is such an arrangement. That local died quickly, as the A.F. of L. took no interest in it.

The fact that an industrial union, embracing all workers regardless of skill, race, sex and age should be built, does not mean that the minority of skilled workers are to be neglected. It is quite possible that, for example, the tool and die makers who are paid less than union men of similar ability in the organized trades, would constitute the backbone of any strike against Ford or General Motors. When questioned on organization and strike prospects the assembly line workers often ask: “Would the tool and die makers strike too?” These men are very important. They were the leaders in the Machinists’ strikes in Detroit and Toledo in 1919-20, as the skilled painters and body builders were the leaders of the Auto Workers Union during the period of its greatest strength. And it is these more skilled groups that have resorted in recent days to scores of sporadic strikes in an effort to redress their grievances. They must be appealed to as the most strategically important elements of any mass movement.

Departmental Delegates

Shop committees, as Robert Cruden suggests in his article in this issue of Labor Age, will certainly have to be used as a basis for agitation by the union that organizes this industry. For the shop and not the geographical local is the natural unit of representation and the place around which union activity must center. Both secret and semi-secret shop committees should be employed to prepare the way with education and propaganda for the first wide-sweeping rebellion of workers. This departmental penetration will be the first step taken by the union in making contacts with workers, and in helping them to evaluate grievances and to give expression to demands. Unless these departmental delegates are trained from the start there will always be the danger that the mass of workers, enrolled during a wide open campaign, will be swallowed faster than the union can digest them, and they will not become really conscious and disciplined union members. According to officials of the Auto Workers Union this was one of the mistakes of its 1919-20 campaigns when the national membership of that union rose to 45,000 in some 35 locals.

The union education of the workers will take various forms, but certainly they will respond only to a union that makes full use of the shop paper method of propaganda. ‘ Such a paper helps them to formulate grievances and give shape to demands. It applies to particular plants and companies and has a direct, personal appeal not contained in the general union or labor newspaper. These papers are needed, furthermore, to offset the “employee magazines” issued by Studebaker, Budd, Buick, White Motor, Cadillac and other companies. They must be made vivid, colorful, and accurate organs of labor, dramatizing the day-ten day struggles and demands, and countering the incessant propaganda of the employers who have such manifold outlets for duping and misleading the workers.

Labor Age was a left-labor monthly magazine with origins in Socialist Review, journal of the Intercollegiate Socialist Society. Published by the Labor Publication Society from 1921-1933 aligned with the League for Industrial Democracy of left-wing trade unionists across industries. During 1929-33 the magazine was affiliated with the Conference for Progressive Labor Action (CPLA) led by A. J. Muste. James Maurer, Harry W. Laidler, and Louis Budenz were also writers. The orientation of the magazine was industrial unionism, planning, nationalization, and was illustrated with photos and cartoons. With its stress on worker education, social unionism and rank and file activism, it is one of the essential journals of the radical US labor socialist movement of its time.

PDF of full issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/usa/pubs/laborage/v28n04-Apr-1929-Labor%20Age.pdf