An excellent introduction into the social landscape of Butte, Montana by Frank Bohn. Socialists had recently won the elections there, a city with, arguably, the most conscious working class community in the country’s history.

‘Butte’ by Frank Bohn from the International Socialist Review. Vol. 13 No. 2. August, 1912.

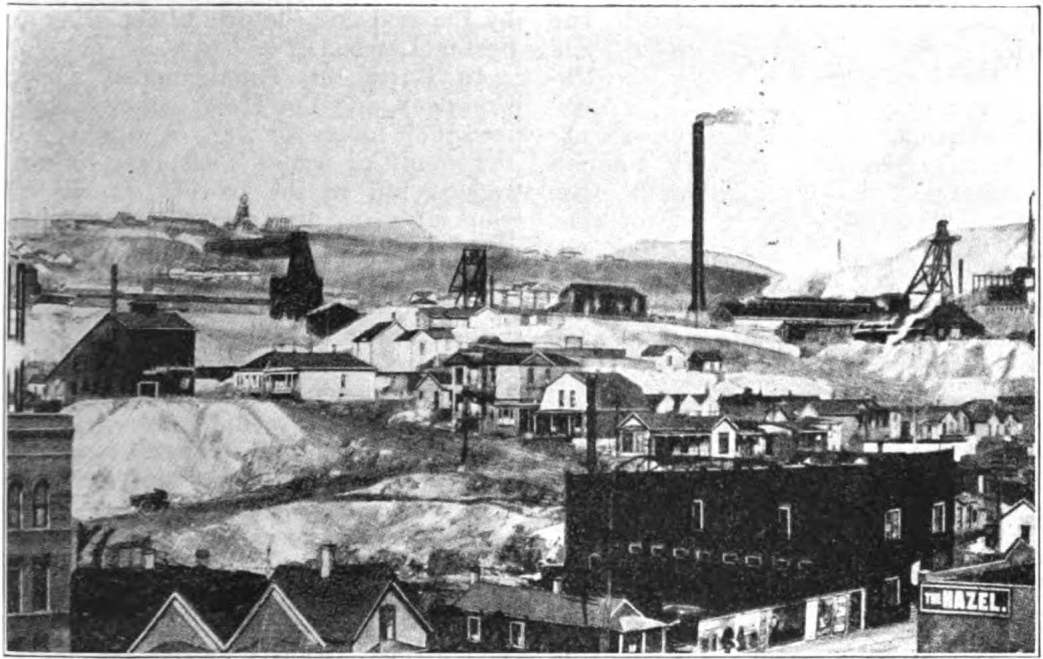

Butte, Montana has a hill. It is not a very big hill. It rises to an elevation of only a few hundred feet, yet it is distinguished in a way which makes the average American citizen speedily forget Olympus, Mt. Sinai and Bunker Hill. Any member of the Butte Real Estate Dealers’ Association will “point with pride” and say, “That is the richest hill in the world.” And so it is.

In the bowels of that hill, up and down and in every direction of the compass. an army of six thousand men has toiled through many thousands of miles of diggings. Three thousand feet below the surface the earth rumbles and roars as though rent by a volcano. Up comes the ore which the mills and smelters speedily turn into $30,000,000 worth of copper annually. Of this sum $10,000,000 goes to the workers who perform all the labor of production below and above ground. $20,000,000 goes to the stockholders in the East and in Europe. Last year forty-seven miners went down into this hill and came out dead. In far away Boston, which owns most of the copper stock, at the end of the year a number of dear kind-hearted old ladies and gentlemen went down town, called on their bankers and learned that they were several million dollars richer than the year previously. Then they went to church and thanked God for the number and excellent quality of his blessings. Now the six thousand one hundred and twelve who compose the Butte Miners’ Union say they do not like this arrangement. They are saying so with considerable vigor and effect. What they are saying and how constitutes our story.

The Crimes of Amalgamated.

Do you remember the great story of Tom Lawson’s which shook the land way back in 1904 and which gave birth to the whole tribe of muck-rakers? The whole nation read through reams and reams of Tom’s curious jargon, breathlessly awaiting exposure of the “crime” and at the end of it all the culprits appear to have performed the very common Wall Street trick of selling more stock than was originally advertised for sale. Only those versed in the ethical standards of the street ever comprehended why Lawson was led to call this a “crime.” Whatever it was it happened in far away New York and when it was over some middle-class parasites had been separated from their dollars. І can remember throwing the copy of Everybody’s Magazine which contained Tom’s last chapter through the window. I was keyed up for a real big blood-curdling crime, with detectives finding dead bodies buried in the cellar wall and all that. And then to come upon this at last—Tom Lawson and some of the other small fry had lost their little all to the Standard Oil gang.

The Real Crimes of Amalgamated.

And our disappointment was so unnecessary. Butte had a story to tell which had we gotten it then would have satisfied the most morbid hunger aroused by the zeal and rhetoric of the crime exposing Lawson.

In Butte the Amalgamated Copper Company and the Heinze crowd organized their forces for war. And what were the spoils of war? That very hill—the richest hill in the world. It was the working class dupes who were used for the fighting. Agents of the two robber bands organized a reign of terror the like of which the industrial life of the modern world has probably never approached elsewhere. There were pitched battles in the streets and men were shot dead. In the depths of the mine two gangs of workers would find themselves face to face and fight like hyenas for their masters. The Amalgamated agents armed their men with hoses and pumps to squirt lime-water upon the enemy, horribly burning and blinding them. Heinze gave his men guns and told them to defend themselves. Where were the police? Why did not the prosecuting attorneys and the judges get busy? What about the priests and the parsons? Bless you, this whole crowd were in clover. It was honey-making time. One judge got a hundred and fifty thousand dollars for a single decision. Thirty thousand dollars were offered for the vote of a single member of the legislature. And no priest or parson preached sermons so poor that he could not during those times have builded for him a magnificent temple of worship.

These were the real crimes of Amalgamated—bribery, thievery, social war, murder raised to a profession and paid for by the piece, blinding men’s eyes with limewater. To one unfamiliar with present day capitalism in America this may seem extraordinary. Tell the story to the old ladies at Boston who draw such huge slices of the Amalgamated profits and they will, no doubt, say that it was all very naughty. As a matter of fact there never was a day when working class conditions in Butte were not preferable to those in Boston. It was during this stormy period just described, that the workers forced the eight hour day and the minimum wage of three dollars a day. Since then Butte has gone on in comparative quiet. And the miners’ union has been strong enough to hold what was then gained.

The Town.

Butte is entirely a mining camp—the largest in the Western hemisphere and second only to Johannesburg, South Africa. In a town of 40,000 people Local No. 1 of the Western Federation of Miners has 6,112 members. The Butte Engineers, also affiliated with the Western Federation of Miners, has five hundred members and there are probably more than five hundred people directly at work for the Amalgamated Copper Company in its offices and stores. The great camp has the appearance of a modern city. Its stores and office buildings compare favorably with those of a Middle Western or New England city of 100,000 people. Only the shacks in which the miners live are less substantial than those of their fellow workers in the East. The town is located in the center of a basin, walled about by high mountains. In the middle of this basin rises the wonderful hill. Coming into Butte at night one sees it far below at a distance of ten or fifteen miles—its myriad of electric lights making a scene strangely in contrast to the wretched scenes by day.

The Work.

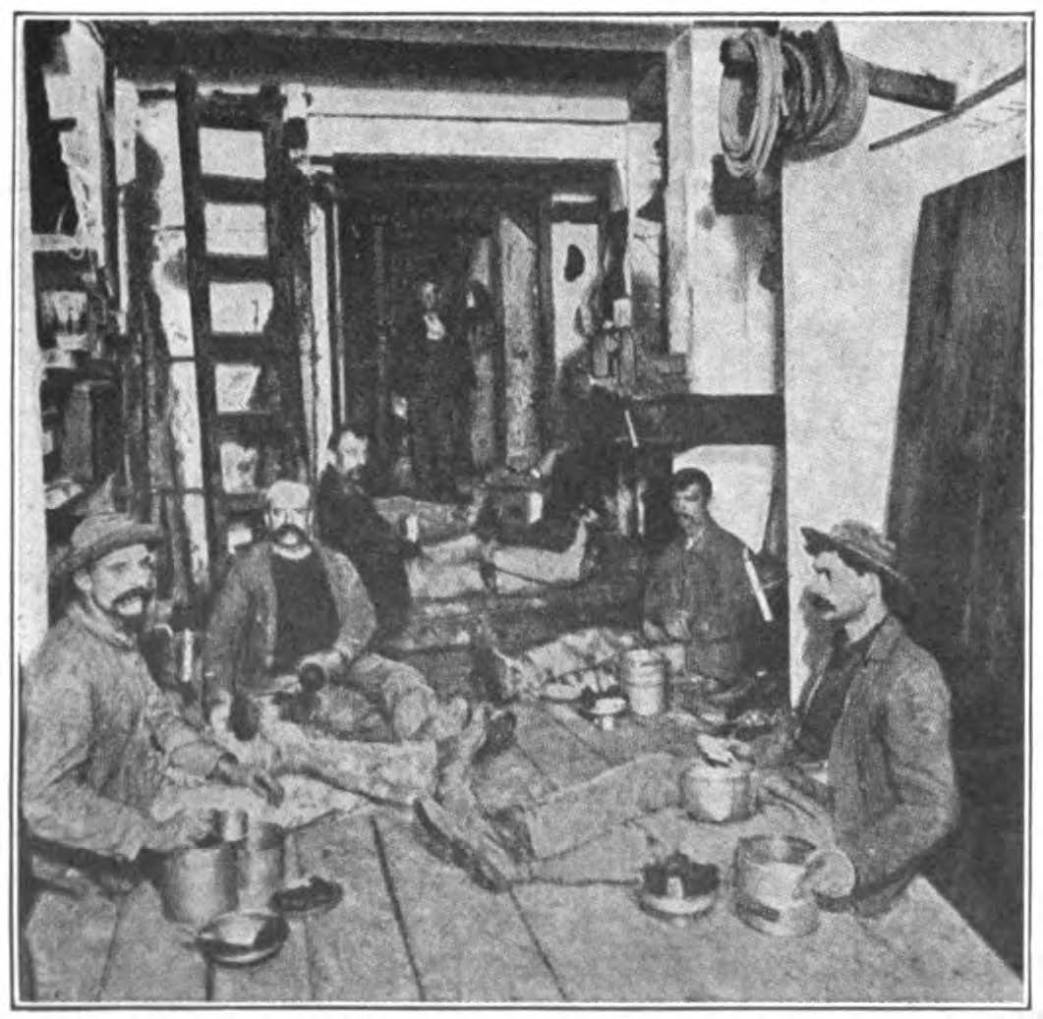

The Butte one sees above ground is only an incident. The real Butte is under ground. Work never ceases, except for an occasional general holiday. The 6,000 miners are divided into three shifts. They go down in the cages which are used to bring up the ore. A drop of let us say 2,000 feet, sometimes even 3,000 feet, is said to brace a man’s nerve for the days work. No time is lost on that trip. I have no accurate information but I surmise that the speed of one of those cages is at least three times as great as that of the most rapid service in a New York or Chicago skyscraper. All that the cable and cage seem to do is to break the fall at the bottom. Inside the mine there are four general divisions of the workers—first, the miners or machine runners who drill for blasting, second, the muckers or shovel men who load the ore, the carmen and finally the timbermen who set the solid timbers which keep the roof of this great workhouse in its proper place. Above ground are laborers, mill and smeltermen, engineers, blacksmiths and machinists and ropemen. These last make and keep in repair the great cables which raise and lower the cages. It is really impossible for a normal man to do mine work more than eight hours a day and live. When the shift lasted twelve hours the miners necessarily loafed some on the job. Even eight hours a day every day in the year uses up human material in a frightful way. A miner who had lately visited the graveyard told me how early the faithful in Butte go to their reward. Few miners he said live to be over fifty unless they stop work. Great numbers die before they reach forty. By far the greater portion are men between twenty and forty years of age. Working conditions depend much however upon the mine. In some mines the air 1s easily replenished and the temperature within comfort. Others are veritable hells for heat, bad air and life destroying vapors. The pest of Butte is miner’s consumption. This disease afflicts great numbers of the women and children who catch it from the men. Last year two hundred men were killed or dangerously injured while at work in the mines. The worst accidents are falls of rock, and premature explosions of dynamite.

The Men.

On miners day I saw this army of 6,000 men march through the streets. Certain characteristics stand out very clearly. The metal miners of this country are probably as sturdy a class of men physically as the world has. Weaklings do not apply for jobs at the end of a piece of hickory in a quartz mine. The conditions of labor develop a fearlessness of danger. Men who are drawn from other occupations quickly respond to these conditions. The members of the working class generally are broken in spirit and saddened by the environment of their labor and life. Not so with the Western miner. While life lasts he is as merry as can be. The constant danger develops in him the philosophy of fatalism. Each day will take care of itself and in every glass of beer there are smiles and heart throbs. The younger men are in the habit of joking about their work. Even the most unclassconscious realize what a “tough graft” is a job in the mines. A slave will come out of a New England textile mill and stop moving and living until he goes in the next morning. Perhaps the happy-go-lucky atmosphere of Butte is caused largely by the fact that so large a portion of its population is of Irish extraction.

The average western miner is therefore a strong man physically. He eats the best food which his relatively high wages permit. If he is unmarried the chances are that he takes a vacation at every possible opportunity and goes fishing or hunting. He spends his money more freely than any other wage worker in the world. Hе never whines or grumbles. When as a union man or a socialist he goes out to fight, joy is in his heart. His method of fighting may not always suit the aforementioned old ladies of Boston but it is quite likely to succeed and that is all he cares about. These are the conditions and qualities which have placed the Western miners in the front rank of the labor movement.

The Union.

In accounting for the Western Federation of Miners another distinction should be made between the metal mining industry and other industries. A railroad worker who has not read socialist literature is usually unaware of the amount of wealth produced by his labor. He works and gets wages. The stockholders get profit. In a vague way he realizes that other people are rich and that he is poor. But that this wealth is a product of his labor—that he is not so readily aware of. How different is the metal mine. Here the whole process of production is right before the eyes of the men. Let us say that a hundred men working in a mine produce $1,000 worth of gold, silver or copper a day. They know their product is ten dollars a piece. If their wages are three dollars each it does not take a professor of mathematics to calculate how much goes to the profit taker. They say to themselves, “Why not take four dollars of the product, or five?” To them the mine manager cannot reply that the eight hour day would abolish profits and close down the mine. Right here we come smack upon the greatest and most far reaching idea that has come to humanity in the modern world. Of that more later.

Local No. 1, W. F. of M.

Local No. 1 of the Western Federation of Miners was organized in 1874. In numbers it is the greatest local labor organization which ever developed in the American labor movement. It is not composed of angels and its majorities have not always been clear as to the purpose of the organization and the interest of their class. In it have developed conflicting views and divers purposes. But the work of this union has nevertheless been significant. It was among the first to secure the minimum wage and the eight hour day. The “mucker” in Butte mines now gets $3.75 a day. Judging roughly I would say that $3.75 in Butte is equal to $2.50 in a town of equal size in the New England or the Middle West. If there has never been a really great strike in Butte this is largely because the forces of the enemy have feared a test of strength with this strongly organized body of men. The mine owners have tried to control the union through diplomacy and compromise. The managers of the Amalgamated have developed a skill in labor politics which, so far as I know, is nowhere else equaled. Butte is infested by capitalist spies. These are the bete noir of both the socialist party and the miners’ union. Of course, they are not without influence, otherwise they could not draw their salaries. In Butte One Big Union with the socialist party as its political expression faces one big trust. The tactics employed on both sides are a prophecy of what is to take place in the whole country as both capitalists and workers continue to organize. It is a warfare characterized on the side of the capitalists by intimidation and bribery, and on the side of the workers by ever greater efforts to organize more thoroughly and educate more intensely. The Butte Miners’ Union subscribes regularly for 1,000 copies of the Appeal to Reason and 250 copies of the INTERNATIONAL SOCIALIST Review. It has been working in perfect harmony with the socialist party administration of the city. By skillful manuevering Amalgamated laid off six hundred socialist workers on the eve of the spring election. But there is never a let up in the work of preparation. “We have a great host of new members,” the union officials told me, “who are not yet revolutionists. Give us time.”

In some sections of the West the Western Federation of Miners seems to have lost its old time spirit. Not so in Butte. What has been lost elsewhere has been gained here. And in seven years what a change! A personal experience will suffice to indicate this development.

Seven years ago upon the request of the general officers of the Western Federation of Miners, I attended a meeting of the Butte miners. I was to address them on industrial unionism. Out of a membership of five thousand at that time twenty or thirty were said to have been in attendance. But I never even saw them. At a quarter of nine the doors were locked and the hall was dark. The little clique who operated the union for the Amalgamated Copper Company had quickly called the “meeting” to order and adjourned. In June of this year I went again to Montana, this time as the guest of that very local union and at the request of its officials I spoke to them on Socialism and industrial unionism.

The opinions of these officials squared exactly with the position I had intended to advocate in 1905. In 1905 I spoke to the Socialist local of Butte. It contained about forty members and was not considered seriously by the powers that were. In 1912 I had the pleasure of meeting the Socialist mayor, councilmen and other municipal officials. May we dare to conclude that the progress of working class in Butte is an indication of its general development throughout the country?

The Socialist Party administration of Butte and its most successful work I shall discuss next month.

The International Socialist Review (ISR) was published monthly in Chicago from 1900 until 1918 by Charles H. Kerr and critically loyal to the Socialist Party of America. It is one of the essential publications in U.S. left history. During the editorship of A.M. Simons it was largely theoretical and moderate. In 1908, Charles H. Kerr took over as editor with strong influence from Mary E Marcy. The magazine became the foremost proponent of the SP’s left wing growing to tens of thousands of subscribers. It remained revolutionary in outlook and anti-militarist during World War One. It liberally used photographs and images, with news, theory, arts and organizing in its pages. It articles, reports and essays are an invaluable record of the U.S. class struggle and the development of Marxism in the decades before the Soviet experience. It was closed down in government repression in 1918.

PDF of full issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/usa/pubs/isr/v13n02-aug-1912-ISR-gog-ocr.pdf