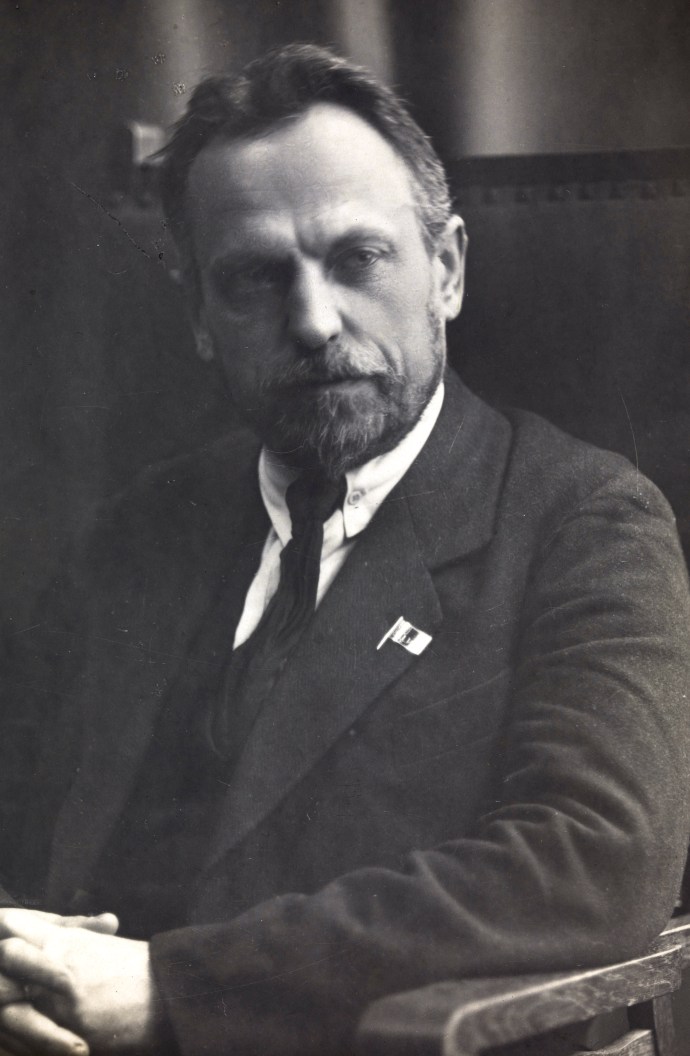

‘The Soviet Power and the Public Health’ by Nikolai Semashko, People’s Commissar of Health from Soviet Russia (New York). Vol. 4 No. 10. March 5, 1921.

TO FORM an idea of the profound change brought about by the November Revolution, we must look into one of our “peaceful” activities: the protection of public health.

This activity felt the influence of the March Revolution less than any other. The March Revolution was as unfruitful for the medical organization and the practice of medicine as the biblical fig-tree. The November Revolution succeeded to what had existed in January: the same selfish bureaucracy, the same “hierarchy” of medicine (the best for the rich, the “leavings” for the poor) camouflaged by middleclass, democratic slogans, such as: the best medical aid free and accessible to all. But the most important point, the organization of medical affairs, was absolutely wrong. The landowners and capitalists were not at all concerned with the health of the masses of the people; all they did was mend the health of the worker just enough to drive him back again to the sweat-shop. The result of such organization appeared in the budget as follows: 95 per cent of the whole budget (a very small one, of course) was fixed for medicaments, and only five per cent for prophylactic (the most important) medicine.

Under the old regime it could not be otherwise. As long as labor was unprotected, the health of the workers was unprotected. Regulations for the protection of labor ran up against an insurmountable wall—the interests of capitalist profit.

The bourgeoisie permitted only the discussion of mothers’ and children’s health protection, but never indulged in any serious reform. Without wholesome living quarters, good health is an impossibility; private property has secured the apartment houses for merchants’ wives with their lapdogs, while underground dwellings are allotted to workers’ wives with their children. Caste (i.e., class) medicine is inevitably bound up with the capitalist system.

The Soviet Government has done away with this deplorable state of affairs. It has surmounted the difficulties brought about by private property and profits. Medical activities are no longer hampered by social obstacles. Labor protection has taken children out of the factories; it has given sick-leave to women before and after childbirth; it has accomplished many other reforms, but, most important of all, it has entrusted the workers to the trade unions by turning over entirely to the latter all questions of labor protection.

The socialization of buildings and apartments made it possible to rescue pale-faced, weak, and sickly children from their basement dwellings. Nowhere else in the world has so much been done for the children as in struggling Soviet Russia during the last three years. Hundreds of thousands are now living in colonies housed in the former luxurious homes of the parasites of the working masses and their lap-dogs. This destitute republic, for the first time in the history of the world has introduced gratuitous feeding for children to the age of sixteen; for the first time also, it has been declared that there are no criminals under eighteen years of age, that they are only violators of law, mentally or physically sick, to be cured either under the Commissariat of Education or under that for Public Health; but not to be taken before the common law courts. For the first time, also, physical care and entertainment are being thought of. Children’s establishments, such as orphan asylums, homes, etc., are increasing from day to day; for the protection of mothers and children, we have 402 establishments (of which 123 are asylums for babies and minors, 151 creches, 100 consultation depots and milk kitchens, 80 homes for mother and child, and lying-in hospitals).

In the sphere of medical science, medical aid is accessible and absolutely gratis to all. The number of sanitariums for the civilian population has, in spite of all kinds of difficulties, increased about 80 per cent over that of pre-war times. Over 100,000 beds were organized for use in epidemics last winter.

A long stride forward has been taken in regard to quality of medical service. In the sanitariums for tuberculosis (in the Russian Federal Soviet Republic alone, the other Soviet republics not included) more than 20,000 new beds and 100 new ambulatories for venereal diseases were established. Six are still to be opened (in the territory of Soviet Russia alone). New establishments of so high a grade as physical-mechanical therapeutic institutions were created (five are to be opened). Health resorts, once resorts of recreation and debauchery for the bourgeoisie, have been transformed into real health resorts for workers; according to incomplete statistical data, our health resorts (not including the Crimea) were frequented last summer by 65,000 patients, 75 per cent of whom were workers, peasants, and Red Army soldiers. All healing powers and remedies have been taken from private individuals and placed at the service of the whole nation. The private sanitariums have ceased to be a means of enrichment to their proprietors, and are now nationalized; the sale of drugs by speculators has been stopped, and all drugs are now in the hands of the government.

Special attention has been given to the Red Army. In the field of army-sanitary administration, the Soviet Government inherited only atrocities and brutalities from the Tsaristic regime. Here literally everything had to be created from nothing. We now have 397,496 beds in military hospitals and 242 completely equipped ambulances. We have improved institutions, equipping trains with bathrooms, laundries, and provisioning trains so that they would now be the pride of any European military medical organization. And most important of all, we have a vast rigidly disciplined organ for the valuation of requirements of the Red Army.

All this had to be accomplished under very difficult conditions, known only to those engaged in this task.

Russia has never ceased to be a victim of epidemics. Suffering from cold and famine, ruined by the world war, Russia was overwhelmed by epidemics, one more virulent than another, with spotted typhus, intermittent fever, and typhoid; Spanish influenza and cholera relieved and followed each other. It is a characteristic fact that the former White Guard border provinces (Siberia and Ukraine) infected our Red Army (not inversely) and through them our civilian population. Even their larger food supplies and the aid of the Almighty Entente, could not save them from the results of their sanitary and social laws. Where work, sweating, and ignorance exist, there will always be epidemics: the best remedy is Socialism.

What gave us the power not only to fight epidemics, but to overcome other difficulties as well? How did the Soviet power overcome them? Most of all by the mobilization of the whole population:

“The health of the working class is properly the worker’s affair.” We not only preached but practiced this. Anti-epidemic commissions, made up of workers, peasants, and soldiers of the Red Army were organized “to fight for cleanliness” in every city, in each body of troops, and in the villages. Every important sanitary decision was first discussed with the representatives of the trade unions, the women’s division, and the young people’s organization, and then it was executed. The whole task was supported by an educational activity unknown before not only in Russia, but in the whole world. The Commissariat for Public Health published during two years (the National publications, the committee in memory of W. M. Bonch-Bruyevich and the local publication not included) over 8 million announcements, 395,000 placards, and 434,000 copies of popular pamphlets. Only the cooperation of the whole working population made it possible to overcome difficulties which sometimes seemed insurmountable.

Indeed, there is still much to be finished, much more to be begun, there are still defects and imperfections. But in spite of these we survived the most critical period and have come off victorious. The most difficult achievements lie behind us. The future is guaranteed by the amelioration of our position in general, the social basis on which we stand, and the experience which we have acquired.

Soviet Russia began in the summer of 1919, published by the Bureau of Information of Soviet Russia and replaced The Weekly Bulletin of the Bureau of Information of Soviet Russia. In lieu of an Embassy the Russian Soviet Government Bureau was the official voice of the Soviets in the US. Soviet Russia was published as the official organ of the RSGB until February 1922 when Soviet Russia became to the official organ of The Friends of Soviet Russia, becoming Soviet Russia Pictorial in 1923. There is no better US-published source for information on the Soviet state at this time, and includes official statements, articles by prominent Bolsheviks, data on the Soviet economy, weekly reports on the wars for survival the Soviets were engaged in, as well as efforts to in the US to lift the blockade and begin trade with the emerging Soviet Union.

PDF of full issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/usa/pubs/srp/v4-5-soviet-russia%20Jan-Dec%201921.pdf