A fantastic article, this look at Detroit labor and the auto industry at the beginning of the Great Depression by ‘a Detroiter’ for A.J. Muste’s Labor Age. The essay looks at the history of organizing in auto, the failure of the 1929-1930 strike wave, the role of the Communist-led Auto Workers Union, the union bureaucracy, the diminished class consciousness of home-owning workers, automation, racial and ethnic divisions, the effect of the Crash of 1929, speedup, and much more. An invaluable background to today’s events.

‘Hard Times Hit Detroit’s Auto Workers’ by A Detroiter from Labor Age. Vol. 20 No. 3. March, 1931.

BEFORE the war, the automobile industry was still in its swaddling clothes. Production was gradually increasing but not to such an extent as to captivate the imagination of the investing public. The motor car had not as yet attained its present popularity. The average worker was not receiving sufficient remuneration to equip himself with a flivver. Then the war came. Automobile factories were converted into munition plants. While the boys were spilling their blood on the poppy-grown fields of Flanders, the motor magnates were receiving fat, juicy c6ntracts from the government; contracts, which permitted them to overhaul their factories — to replace worn-out machinery with new and more labor-saving equipment. With the coming of peace, the automobile magnates had plenty of cash and modern industrial plants ready to be turned into the production of motor cars. Henry Ford, that great philanthropist, built a huge factory on the banks of the Rouge River at government expense. The pathetic Lelands, father and son, persuaded the government in the name of liberty to erect a plant for the production of Liberty motors, and, when peace came, bought it for a song and used it to produce Lincoln cars.

In short, the motor industry was in excellent shape not only to produce cars within the reach of the average man’s pocketbook but to popularize the use of motor cars. The automobile industry, which was of relatively small importance before the great “war for democracy,” had attained a commanding position among the great manufacturing industries of the country. In 1925 the value of products of the automobile industry exceeded that of any other industry. In 1913 the production of passenger cars and trucks in the U. S. was 485,000 and in 1920 it had reached the staggering total of 2,227,300, an increase of 600 per cent.

Orders came pouring in. During the years following the war, it was necessary to wait several months before delivery could be made. The magnates become millionaires, and in some cases, billionaires. The 21 manufacturers in the automobile group, not including the Ford Motor Co., in 1928 made a net profit of $399,136,000 on a capital and surplus of the beginning of the year aggregating $1,430,648,000, or a return of 27.9 per cent, as compared with an average return of 12.1 per cent of all corporate industry in that year.

Calling for Labor

With a phenomenal increase in productivity came a shortage of labor. The automobile companies sent labor agents, south, east and west. The farms, mountains and plantations were drained of their labor. Gawky mountaineers, timid plantation workers and stolid plough hands were persuaded to come to Detroit, the paradise of labor, where wages were high and jobs plentiful. In 1914, the average number of wage earners in the automobile industry was 127,092 and in 1919 it rose to the amazing figure or 343,115. Ford, with his excellent press service, broadcasted to the entire world that he paid the highest wages; that his workers were the most contented and that the conditions under which they worked were ideal. Of course, the U. S. Department of Labor had not as yet investigated the budgets of his workers, and had not as yet discovered that in 1929 his workers had an average total income of $1,711.87, and an average expenditure of $1,719.83, leaving an average deficit for all families of $7.96.

As a consequence Detroit’s negro population is now 120,000; the southern drawl is as common as in Arkansas and the mark of the hayseed is as common as in Podunk. We are all aliens in Detroit, the motor city.

In most of the branches of the industry, skill was not necessary. As Ford pointed out in one of his recent books, 43 per cent of all jobs in his plants required not over one day of training, 36 per cent from one day to one week, 6 per cent from one to two weeks, 14 per cent from one month to a year and 1 per cent from one to six years. It appears then that 85 per cent of his workers could learn their tasks within one month.

The mountaineer, within a few hours, was turned into a competent lathe — milling machine or drill press operator. Strength and vitality were more important than intelligence. The conveyor system placed a premium upon youth. To secure a job a thick bicep and a healthy, corn-fed look were the passwords. However, unfortunately for the motor magnates, there were certain processes that still necessitated the use of skilled labor. It was extremely difficult to teach a farm hand to trim, paint, bump or finish automobile bodies within a few hours. The work was too fine. As a consequence, those employed in this type of work became the aristocrats of automobile labor. It was common for a body bumper or trimmer to earn $18-$20 a day. Using bonuses and piece-work rates as incentives, these workers were speeded up to a high degree. With good wages, they became somewhat arrogant and were not as docile as is expected of American workers. They would not hesitate to lay off for a day or two for dismissal to them meant nothing. Jobs were too plentiful to make the discharged worker concerned about the future. Something had to be done to curb their spirit. The magnates bided their time.

As the industry became more stabilized, much money was spent in inventing machines which would displace these skilled workers. The duco sprayer mechanized, the painting of automobile bodies. By means of an electric welding process rear quarter body panels can now be welded together by an unskilled man at the rate of 60 welds per man per hour, whereas, previously, a skilled man using the torch method did only 12 in the same period. A machine for manufacturing pressed steel frames, operated by one man, now produces six frames or more per minute or 3,600 in 10 hours. Formerly, to accomplish this production by the hand method required 175 men. Many other examples can be given. Labor-saving devices were being installed gradually, until the day arrived when the magnates decided to strike. Piece-work rates were cut, bonuses were eliminated. The happy days were over. Jobs were not so plentiful and skill was not essential. It required a full day’s work to earn $7-$8 a day. The workers rebelled. An epidemic of strikes swept over the industry in Detroit. Whereas in the good old days, union agitators were treated with scorn, they now become popular. The Auto Workers’ Union, also known as the United Automobile, Aircraft and Vehicle Workers of America, an independent industrial union, was swamped with membership applications. Formerly known as the Carriage, Wagon and Automobile Workers’ International Union and affiliated with the A.F. of L., because of the antagonism of a number of craft unions, it could not continue to function as an integral part of the Federation. Its charter was revoked in 1918 because of its refusal to strike the word “automobile” from its title. Expulsion did not seem to affect its popularity with the rebellious workers.

Within a few months, the membership roster of this union rose to over 12,000 in Detroit and nearly 28,000 in the entire country. Hope was in the air. Those were the days when the boys thought that the revolution was around the corner and what better evidence was there in support of that belief than the apparent class conscious spirit prevalent amongst the auto workers. Radicals by the score become active in the affairs of the union.

Decline of the Auto Workers’ Union

Although here and there, a small factory capitulated, the big boys kept on rationalizing their plants and importing scab labor. The strikes were lost; the Auto Workers’ Union was reduced to a shadow organization, and the men went back to work at reduced wages and upon the terms of the employers. Since then, with the exception of a sporadic revolt in Pontiac and Flint, the automobile workers have remained quiet — very quiet. True, the Auto Workers’ Union is still in existence, but its membership is less than one hundred. Whether it will under its present Communist leadership succeed in organizing the workers remains to be seen. Most of its members are very sincere and courageous individuals but courage is not enough in this fight.

With increased productivity of the industry and the sudden influx of hundreds and thousands of workers, a shortage of homes developed. Rents were boosted to an unheard of height by avaricious landlords. Real estate values soared skywards. A real estate boom was on. Millions were made in real estate speculation. Farms, miles from the Detroit City Hall were subdivided and lots sold to these new workers. Emphasis upon home ownership was stressed by all organs of thought conveyance. With their high wages, many of these newcomers pictured themselves as home owners, the proprietors of little bungalows with yards big enough for the kiddies to play, and, of course, a garage to house that new car. A spending orgy developed. Credit was extended to workers. Many little towns sprang up overnight, populated entirely by home owning workers; Lincoln Park, Hazel Park, East Detroit, Clawson and many other such Detroit suburbs.

It only required a few hundred dollars down and the rest like rent to change a worker from a renter into a respectable property owning member of society, a taxpayer, if you will. Of course, he did not realize then, that the shack sold him was inflated highly in value, that the materials used to construct it were cheap and shoddy; that it would take him about twenty years to pay what he owned on the house he so proudly called “his’n” and finally that if he defaulted in one payment he would lose his mansion including the money he paid into it. Over 125,000 workers, it is estimated, have already lost their homes during the present depression.

The boom naturally created a demand for building workers. The building trade unions took advantage of the situation and managed to build up their membership. The Employers were so busy that they could not afford a protracted battle with these unions, especially when certain methods, not mentioned in the text book, were resorted to by both sides. Furthermore, a large number of the contractors were little fellows, beginners, as it were, and not able to put up much of a battle. The unions were more interested in job control than in attempting to organize all building workers. When they arrived at the point where jobs could be procured for most if not all their members, they refused to take in the unorganized building tradesman. They became exclusive. As a matter of fact it was necessary to resort to influence and the liberal expenditure of money in order to be accepted as a member by a certain building trade union. And it was only in 1922 that this very union was extremely anxious to take in all comers. They treated the unorganized worker as a scab but when this scab wanted to be regular, his application was turned down.

Not only did these unions refuse to take in the unorganized worker but they also refused to co-operate with each other. Many a strike was lost because the members of one union sabotaged the members of another, and the members of one working while the members of another were outside picketing the job. The larger and more important contractors have waged a pitiless fight with union labor.

“The Citizens’ Committee”

Their mouthpiece, the Citizens’ Committee, which is also sponsored and fully supported by the Detroit Chamber of Commerce and which has as its object “to maintain the American plan of Employment in Detroit has made it possible for Detroit to enjoy an open shop reputation.

The contractors have always believed in a united front but unfortunately the unions, whose strength lies in unity and co-operation from each other, have not taken advantage of the many opportunities presenting themselves. As a result, Detroit building workers have not succeeded in doing as well for themselves as their brothers in New York, Chicago and Cleveland. These building trade unions, together with the typographical machinist and a few miscellaneous unions constitute the Detroit Federation of Labor.

The membership of the unions affiliated with the Detroit Federation of Labor almost tripled during that boom period. Politicians fell over themselves trying to get into the good grace of the labor leaders. Before the Volstead Act became effective, Detroit was more or less controlled by the Royal Ark, a saloon-keepers’ organization. However, with the coming of prohibition, machine politics was dealt a death blow. It was very difficult to determine who had the votes and who could deliver them effectively. Believing that labor always votes in a solid bloc, these aspiring job seekers visualized twenty thousand votes lying around the vest pockets of its leaders. Naturally agreements were made; promises were given and in the case of those aspiring to wear the royal ermin, it meant that in the future when a union man fell into the clutches of the law, especially while in an intoxicated condition, he would not have to spend all night in the company of bums and other disreputable members of society.

At first, this power was used solely for union men, but gradually, when certain labor leaders realized that prohibition violators, prostitutes and gamblers were willing to pay handsome sums to those who would make it possible for their immediate release when arrested, they took advantage of the opportunity. Money came in fast and easy. Alley whiskey was then selling as high as $15.00 a gallon and fortunes were made overnight in that new industry. Labor leaders began consorting with gangsters, pimps and bootleggers. As soon as certain members of the underworld were arrested, a friendly judge was reached and the police notified to release the prisoner until the following morning. An alliance was therefore made between trade unionism and the underworld.

The alliance continued for some time. However, the bootlegging business became stabilized. It was much cheaper to bribe police officials than be arrested and pay fixers handsomely to be released. The bootleggers became so powerful that it was not necessary for them to use middlemen to reach certain politicians. Business for these labor leaders began dropping off. Some new source of revenue had to be discovered.

The Dyeing and Cleaning Blot

Someone conceived the idea of organizing all the small cleaning and repairing shops into a union affiliated with the Detroit Federation of Labor. Naturally a large number of these merchants were not eager to become members of this proposed union. Argument and logic had no appreciable effect upon their apathetic attitude towards organization. Some other weapon had to be used. Imitating Chicago, the organizers of this union engaged the services of their underworld friends, who, with the liberal use of stench bombs and other malodorous missiles, made it possible for this merchant union to develop rapidly. The entire affair forms a sordid chapter in the history of the Detroit labor movement.

It later developed that these underworld thugs were also used by the wholesale cleaning and dyeing plants to crush this union. A number of men were killed. Sometime later, a very prominent trade union official was tried for extortion but fortunately acquitted by a jury. The complaining witness was the head of the largest cleaning plant in the city.

The Detroit Federation of Labor also helped to organize jitney drivers, men who owned automobiles for hire and who in order to remain on the streets of Detroit paid tribute to a prominent attorney and his labor allies; kosher butchers, bread wagon drivers and other petty merchants. At no time was there any serious effort made by the Detroit Federation of Labor to organize the great mass of automobile workers.

It is true that the American Federation of Labor did make a gesture in that direction. In 1926 when the American Federation of Labor held its convention in Detroit, a resolution was passed calling for “a conference of all national and international organizations interested in the automobile industry for the purpose of working out details to inaugurate a general organizing campaign among the workers of that industry. The A.F. of L. intended to show Ford, Sloan, Macauley and other motor magnates that their employes could and would be organized. All predicted a battle between giants. In one corner was the A.F. of L., and in the other, Billionaire Ford and his friends. An organizer was sent to Detroit and upon his arrival he invited 17 A.F. of L. craft unions claiming jurisdiction over auto workers to a conference to agree upon a line of policy. This conference was held on December 1, 1926 and it was then decided to again convene the representatives of the various interested international unions with the recommendation that each of these representatives have full authority to waive all jurisdictional claims.

One Auto Union?

At this conference it seemed extremely difficult to convince some of the delegates that the auto workers, before they could be effectively organized, would have to be taken into one union in order to wage an effective fight against their employers. However, it was agreed to refer the question of jurisdiction to the respective unions, and at the second meeting it was hoped that the various differences would be ironed out. This second conference was held on March 24, 1927 when it was decided to suspend jurisdictional claims for the workers engaged in all the so-called “repetitive” and unskilled processes in the plants so that temporary local labor unions might be formed for them, directly affiliated with the A.F. of L. The national Federation was to appoint a leader to direct the work in the campaign. The other craft unions were to co-operate in conducting a general membership drive. The agreement arrived at that conference expressly provided, “It shall be the definite aim and avowed purpose of the A.F. of L. to bring about the transfer of those organized in the automobile industry to the jurisdiction of the respective national and international union, this transfer to be effected as speedily as possible.”

However, the campaign fizzled out. The battle of the Titans ended in a smashing victory for the employers. The American Federation of Labor with its craft union basis could no more organize the automobile industry than it could the steel industry. Detroit was still safe for the American Plan. Not only did the A.F. of L. refuse to waive jurisdictional claims but it adopted a rather novel method according to James O’Connell, President of the Metal Trades Department of the A.F. of L., of organizing these workers. Instead of using the old fashioned methods of holding mass meetings, agitating in front of the plants and distributing special union literature dealing with the problems of the automobile workers, the A.F. of L. leaders attempted to induce the officials of some of the automobile plants to enter into a conference with them for the purpose of trying to negotiate an understanding that might result in lessening the opposition on the part of the officials of the companies to unionizing of their employes. How naive the laborites were! The hard boiled motor executives must have had many a laugh when discussing this amongst themselves.

Labor Demand Falling

With increased rationalization and stabilization of the motor industry, the demand for labor is lessening. In 1914 the average number of motor vehicles per worker was approximately 4.5 while in 1927 it had grown to approximately 9.8. Wages have been ruthlessly cut and shut downs are very common. The motor industry is equipped to produce over eight million units each year. In 1929, a boom year, the entire world could only consume about six million units. Ford can easily produce 15,000 cars a day but unfortunately for Detroit workers he is not able to sell his output, and consequently, is compelled to shut down his plants for varying periods. He also is managing to produce more cars with fewer workers, thereby reducing his labor costs and at the same time increasing his profits. Not only that, but the worker, who in 1925 was persuaded to buy that place in the country, is not able, in the year 1931, to keep up the payments. Foreclosures of these long term contracts or land contracts are common. Not a day goes by without one to two hundred homes being taken away from these workers by legal process. As a matter of fact, it pays the worker to give up his home without a struggle rather than keep up payments, for he could buy a better home with the money he owes on the old one. There is a plethora of houses in Detroit for sale. Thousands of flats and homes are vacant. The home owning industry has been debunked in Detroit.

Naturally this situation has affected the building industry and at the same time the building trade unions. The good old days are gone. The building trade worker is no longer the labor aristocrat. He frequents a soup kitchen conducted by the Detroit Federation of Labor and financed by the City of Detroit. About 40 per cent of all trade union members in Detroit are unemployed.

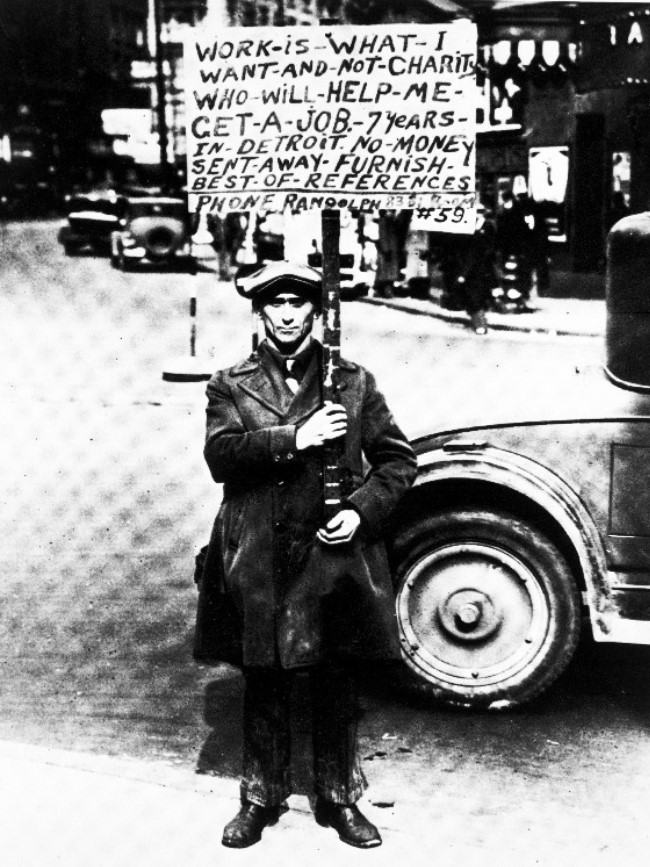

Unemployment is rife in Detroit. One hundred and fifty thousand men and women are walking the streets searching for jobs. At the present time 102,373 unemployed are registered with the Mayor’s Unemployment Committee. Nearly 45,000 families are receiving doles from the Welfare Department, receiving last month over two million dollars. Over 13,466 men are being fed and 6,023 lodged by the City. We proudly claim to do more for the unemployed than any other large municipality. We can point with pride to well equipped soup kitchens, ancient factories used for lodging houses, warehouses full of cast off clothing donated by generous Detroiters and children going to school without food or proper clothing.

With poverty sweeping over the city like a plague, it would be expected to find a strong radical and labor movement. There is no strong organized labor movement in Detroit. That seems to be one of those unexplainable contradictions. With the exception of the unions affiliated with the Detroit Federation of Labor, which has a membership of about 7,000, there is no other strongly organized labor organization. The Communist Party, the S.L.P., the Proletarian and the Socialist Party have small branches here. However, their combined influence seems to be nil upon the attitude of Detroit Labor. One can’t, however, help but feel that the future is not bleak and barren. Somehow or other, one feels that a surging mass rising is in the offing. Here and there indications seem to be that something is going to happen. Detroit Labor is not going to be satisfied with soup kitchens, welfare doles, flop houses and Hoover prosperity. Detroit labor will assert itself, will demand its rights, and, through proper organization and education will secure them.

Labor Age was a left-labor monthly magazine with origins in Socialist Review, journal of the Intercollegiate Socialist Society. Published by the Labor Publication Society from 1921-1933 aligned with the League for Industrial Democracy of left-wing trade unionists across industries. During 1929-33 the magazine was affiliated with the Conference for Progressive Labor Action (CPLA) led by A. J. Muste. James Maurer, Harry W. Laidler, and Louis Budenz were also writers. The orientation of the magazine was industrial unionism, planning, nationalization, and was illustrated with photos and cartoons. With its stress on worker education, social unionism and rank and file activism, it is one of the essential journals of the radical US labor socialist movement of its time.

PDF of full issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/usa/pubs/laborage/v28n03-Mar-1929-Labor%20Age.pdf