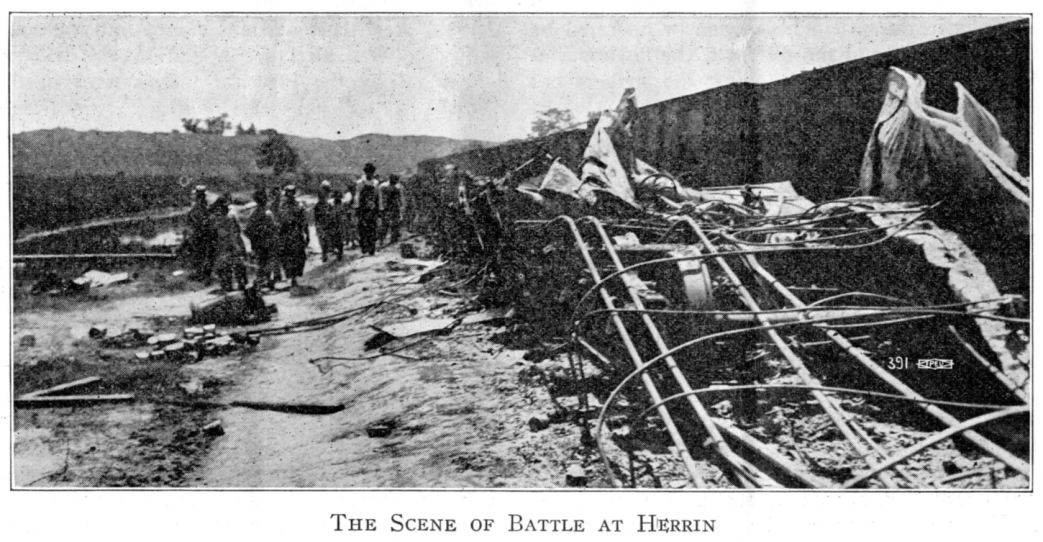

A fine look at the events of Herrin, Illinois in the summer of 1922 by Carl Haessler. Given its implications and consequences, the events of one hundred years ago in the mining community Herrin, Illinois are rarely spoken of, even today. Before Herrin, the predominate force facing strikes were hired guards, Pinkertons, and deputized gangs under the direct pay of the bosses. After Herrin, the force we faced was largely the National Guard and the state directly. Why? During 1922’s national U.M.W.A. strike, in disregard to a previous agreement, 50 armed scabs were brought into the mines at Herrin commanded by notorious strike-breaker C.K. McDowell. Those gun thugs killed several strikers after their arrival and were soon met with a militia of union miners. Armed miners surrounded the scabs. After a fierce gunfight, took their surrender, burned down the mine, and then meted out an enraged justice on the survivors. At least 20 scabs, including McDowell died on June 21, 1922. Our side could strike real fear as well as theirs. Unfortunately, Haessler’s prognosis of peace was premature, as the southern Illinois coal fields, including Herrin soon saw a virtual decade-long civil war between the Klan and progressives miners, including within the U.M.W.A. itself.

‘Peace Reigns at Herrin’ by Carl Haessler from The Liberator. Vol. 5 August, 1922.

THERE will be no scabbing on union coal miners in Herrin for at least ten years to come.

No editorial in the capitalist Press or in the Labor Press, so far as I have read them, has touched on this fundamental result of the massacre in the Williamson county mining town in Southern Illinois. We call the affair a massacre, though only nineteen non- union men were killed and a score or more wounded, while three union coal miners lost their lives as well. In India, when the British kill or wound 1,500 unarmed Hindus, as they did at Amritsar soon after the war for democracy, that begins to look like a massacre, though nobody seemed to care very much, but here a battle provoked by gunmen and lost by them is by common capitalist consent known as a massacre.

The moral issue, the question as to whom to pass the buck, will be decided again in August, when the special grand jury empanelled at Marion, near by, will report. The coroner’s jury of three miners and three business men, the first official body to pass judgment, held the Southern Illinois Coal Company directly and indirectly responsible for the deaths on the testimony of a wounded scab, and named C. K. McDowell, the one-legged company superintendent who lost his life in the outbreak, as the man who had murdered George Henderson, an unarmed union miner, and so started the shooting. When McDowell’s body was found it is said the word scab had been branded or painted on his wooden leg. Attorney General Brundage, of Illinois, has offered $1,000 to any informer assisting the jury to stick someone with the blame.

Leaving the moral issue to the gentleman taking an official interest in it, let us return to facts.

The outstanding fact, pleasant or unpleasant, is that there will be no scabbing for about ten years. Another fact is that a crop of children prematurely born during the excitement, like the Peoria babies born during the trouble there some decades ago (of whom Tom Tippett, of the Federated Press, is one), will grow up with the impress of industrial civil war stamped into their being. As for the events leading up to the Herrin battle, the Chicago Tribune carried an account about ten days late substantially like that reported immediately by the Federated Press. Needless to say, the first reports of the Tribune, sensationally displayed just when readers’ mind were still plastic on the question, gave a very different impression.

Herrin is a small place devoted almost exclusively to coal mining. The principal businesses, according to the Forward correspondent, are in Jewish hands. The civil offices are filled by the organized votes of the union miners. The miners are of American stock, with Italians, negroes, Hungarians, Slavs, and Finns giving an international favour to the community. The owner of the miners’ jobs is William J. Lester (Damned-If-I-Will Lester), president and principal stockholder of the company, which runs a strip mine near Herrin. Ordinarily coal veins are worked under- ground, but when the vein runs near the surface it is cheaper and quicker to strip off the soil with a steam shovel and excavate the coal and load it on cars with another steam shovel. When the coal strike began, April 1st, it sewed up underground mining in Illinois because of a state law forbidding men to mine without certificates based on several years’ experience. Strip mines, also abandoned operations, except to uncover the veins, which was done by union men. Lester worked along under this agreement until the beginning of June, when he ordered the union men to load coal in the cars. They refused, and lost their jobs. Scabs and gunmen were brought in from Chicago, and everything was set for trouble. June 16th a miner in another country wrote to a friend: “Will them hell- hounds go the limit? If the law can’t stop ’em, the men will.” June 21st Henderson, the unarmed union man, was killed. June 22nd the battle was fought.

Before fighting it over again here a bit of Herrin gossip lifting the affair into the largest circles of corporation control will assist in estimating the importance of the scrap. Lester, this story has it, was hard up for capital at the same time that he saw a fortune in strip coal at famine prices if he could only sell it. He could not get a loan from the usual sources, but obtained it in the end, the rumour runs, from United States Steel Corporation quarters on condition that he introduced the open shop and dent a hole in the solid union line-up in the Illinois coal fields. With money in his pocket and riches in sight he could go cheerfully forward.

He knew what the consequences of his determination would be. He told Governor Small hell would break loose unless troops were sent down. When Colonel Samuel N. Hunter, Illinois, national guard, implored him to stop operations to avoid bloodshed, Lester replied: “I’ll be damned if I will.” “He may have had the business advantage of bloodshed in mind. Immediately following the casualties he announced, through his attorney, that he would sue the miners’ union and the county for over a million dollars, citing the Coronado decision of the United States supreme court.

The account of the battle as given by an eye-witness who saw it all through has a Homeric swing. Troy probably was no larger than Herrin, and the casualties on the Trojan plain seldom more serious than these on the Illinois prairie. “Until dark, firing was intermittent,” he writes; a searchlight at the mine was turned upon the attackers. A rush was made to disconnect the power lines. A rush was made over the barbed wire and breastworks which had been erected. An aeroplane was fired upon by machine guns from the mine. Shortly after the aeroplane had flown over-head a white flag was raised by the men in the mine. A truce was arranged. The flag had been up but a short time when several of the armed men who had hoisted it re-opened fire. When it was seen that the flag of truce was being used as a ruse it was decided that no quarter would be granted. The screams of injured men in the pits could be heard above the roar of battle, and a voice shouted to the men that the first man to attempt to leave the pit would be shot. At daybreak the attackers formed in column. They worked their way into the stronghold and captured those who remained alive.”

There were 60 or 70 men in the mine premises. Some were killed during the fighting, some while being led away as prisoners, following heated exchanges of West Madison Street, Chicago, Billingsgate, and the Southern Illinois variety. Nineteen scabs and guards were killed. A union miner dying of wounds on July 13th brought the union death list up to three. There was some rough handling on both sides, but no atrocities of the Belgian propaganda sort. The coroner found a number of scabs shamming severe injuries.

The dead on both sides were buried in the same cemetery.

Wounded scabs in the Herrin hospital were remarkably communicative. Joseph O’Rourke said: “I don’t blame the miners much for attacking us. We didn’t know this was a scab job. We were given arms when we arrived and a machine gun was set up at one corner of the mine. Most of the guards were toughs sent by a Chicago detective agency. The agency was the Edward J. Hargrave Secret Service. Ed. Green told reporters the boss told him he would be shot if he tried to quit the job. Other men gave similar details of being lured to the mine from Chicago under false pretences. The timekeeper of the company guards testified that. Superintendent McDowell had killed Miner Henderson in cold blood. He also said the gunmen’s chief got $14 a day, and the rest $5 a day. McDowell had previously told the sheriff that the unusual quantities of ammunition in the company buildings were being kept ” for ducks.” Asked to withdraw the gunmen, he replied: “I’ve broke other strikes, and I’ll break this one.” He had seen similar service in Colorado and Kansas. At Herrin he made the supreme sacrifice, as it is phrased.

Testimony before the coroner’s jury by police, farmers, business men, miners, the sheriff and women unveiled a record of days of lawless behaviour by company guards before the clash. They picketed public roads, compelling farmers to detour to get to town. They yanked people out of passing autos and searched them. They slapped pedestrians and tried their way with women. A representative of the august Chicago Tribune standing on the highway got a summary invitation to take the air.

The terrorizing was the first break in 20 years of peace in Williamson county. The mine is shut down. The steam shovels are wrecked. The box car living quarters are burnt. The power plant is dynamited. The scabs are dead or gone, except two or three wounded still in Herrin hospital. Gunmen all over the country have made mental reservations regarding service in Herrin. There will be at least ten years more of peace in Williamson county.

Peace obtained in this way is as embarrassing to present society as an illegitimate child. It should have been sanctified in some way beforehand, perhaps by a Wilsonian message to congress, about “voices in the air,” But here it is, like the child. The parentage may be dubious, but the child is quite a strapper, good for at least ten years. And the moralists assert that illegitimacy is a growing evil.

The Liberator was published monthly from 1918, first established by Max Eastman and his sister Crystal Eastman continuing The Masses, was shut down by the US Government during World War One. Like The Masses, The Liberator contained some of the best radical journalism of its, or any, day. It combined political coverage with the arts, culture, and a commitment to revolutionary politics. Increasingly, The Liberator oriented to the Communist movement and by late 1922 was a de facto publication of the Party. In 1924, The Liberator merged with Labor Herald and Soviet Russia Pictorial into Workers Monthly. An essential magazine of the US left.

PDF of original issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/usa/culture/pubs/liberator/1922/08/v5n08-w53-aug-1922-liberator-hr.pdf