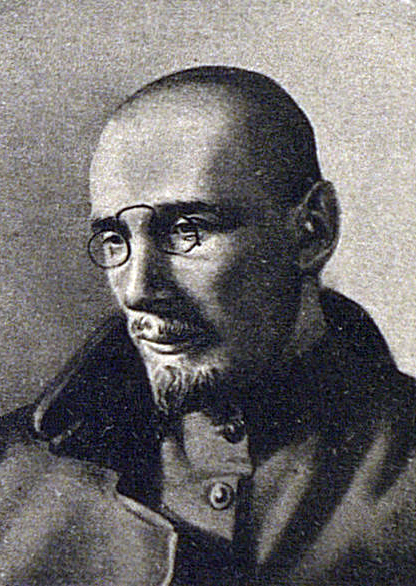

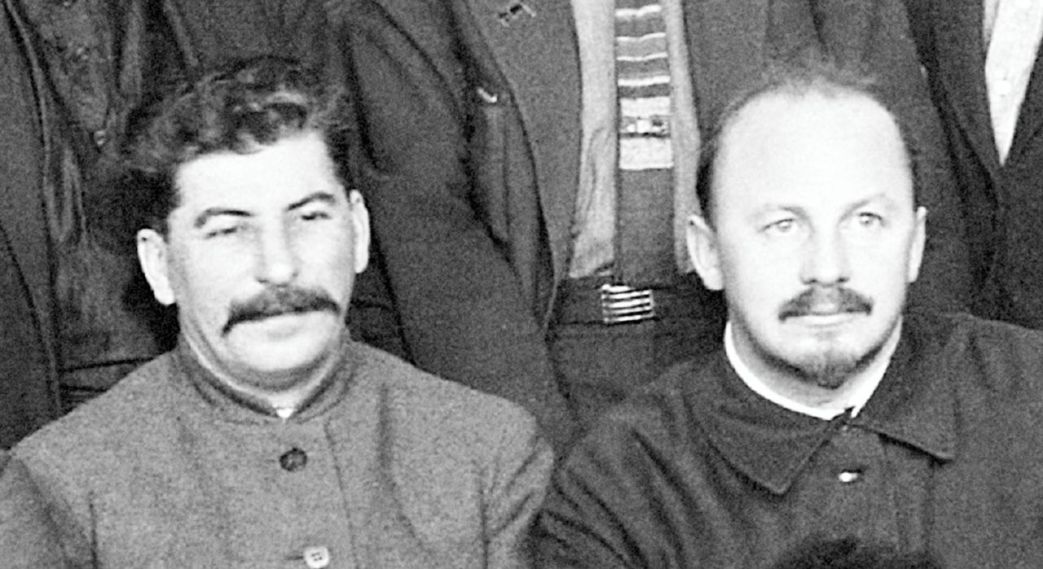

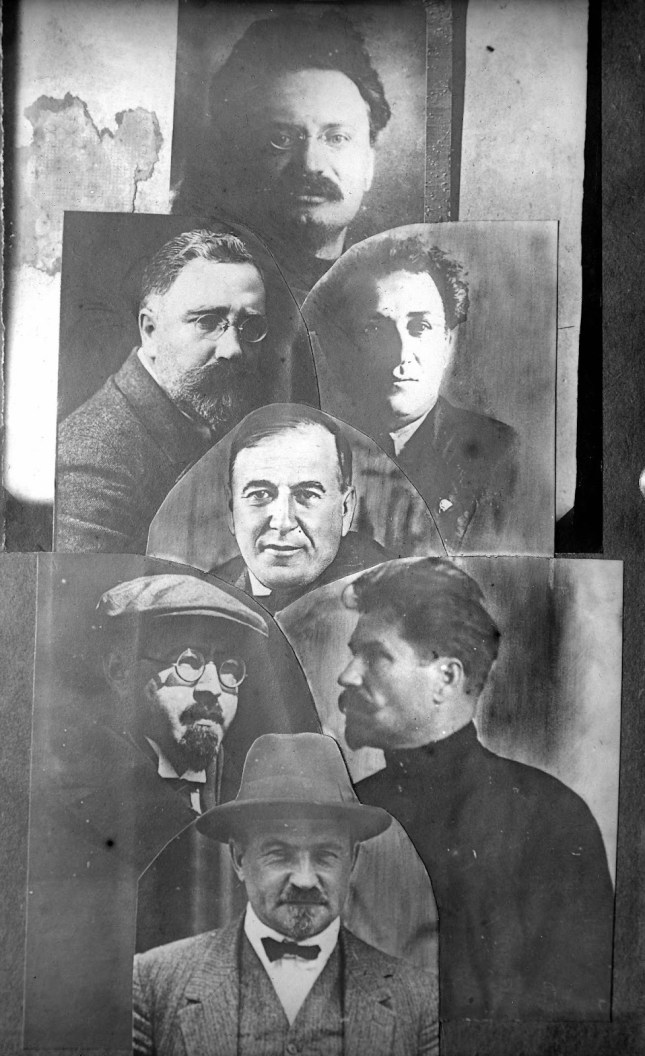

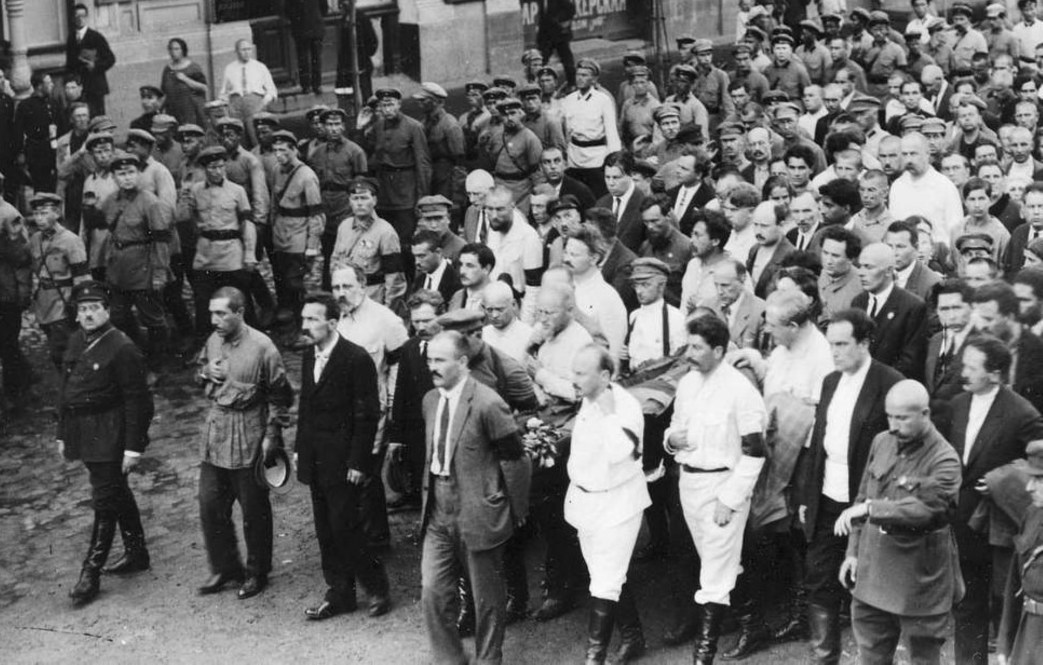

Transcribed online for the first time here is Trotsky’s full final speech as a delegate to a meeting of the Communist Part, his last internal oppositionist fight, and important record of that most consequential of schisms on the Communist movement. The extensive address was recorded verbatim, interruptions, cat calls, and all. The Conference took place in October-November, 1926, focused on combating the United Opposition’s challenge, the assessment of the NEP, and international situation. The United Opposition formed in 1926 after the Bukharin-Stalin faction defeated the ‘New Opposition’ led by of Zinoviev and Kamaenv in 1925. Along with those New Oppositionists based in Leningrad, forces of the old Workers Opposition, along with the variations within Trotsky’s Left Opposition, joined together in a struggle against the Stalin-Bukharin Bloc and the increasingly divisive N.E.P. at the upcoming 15th Conference of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union.

Leading party figures, such as Lenin’s widow Natalia Krupskaya and A.G. Shlyapnikov, as well as thirteen members of the Politburo, Central Committee, and the Central Control Commission, N.I. Muralov, G..E. Evdokimov, H.G. Rakovsky, G.L. Pyatakov, I.T. Smilga, G.E. Zinoviev, L.D. Trotsky, L.B. Kamenev, A.A. Peterson, I.P. Bakaev, K.S. Solovyov, G.Ya. Lizdin, and P.N. Avdeev signed the declaration. With international policy, relations to the peasantry, industrialization, bureaucracy, ‘socialism in one country,’ the legacy of Lenin, and most of all how to move beyond the New Economic Policy were fiercely contentious. The results was a route, with Kamanev, Zinoviev, and Trotsky removed from the Politburo (along with Stalin, Trotsky was the only consistent member of that body since the Revolution). Zinoviev would also be removed from his Comintern leadership. Though retaining positions on the Central Committee, Trotsky, Zinoviev and many other oppositionists would be expelled from the the following 15th Congress (not to be confused with the 15th Conference in late 1927. Because of the length, this speech will be posted in two parts. Second part here.

‘Speech to the 15th Conference of the Russian Communist Party: Part One’ by Leon Trotsky from International Press Correspondence. Vol. 6 No. 79. November 25, 1926.

Comrades! The resolution accuses the Opposition, including me, of a Social Democratic deviation. I have thought over all the points of contention which have divided us, the minority of the CC, from the majority during the period just past, that is, the period in which the designation “Opposition bloc” has been in use. I must place on record that the points of contention, and our standpoint with respect to the points of contention, offer no basis for the accusation of a “Social Democratic deviation.”

THE QUESTIONS IN DISPUTE

The question upon which we have disagreed most, comrades, is that which asks which danger threatens us during the present epoch: the danger that our state industry is lagging behind, or that it rushes too hastily forward? The Opposition-in which I am included- has argued that the real danger threatening us is that our state industry is lagging behind the development of the national economy as a whole. We have pointed out that the policy being pursued in the distribution of national income involves the further growth of the disproportion. For some reason or other this has been termed pessimism. Comrades, arithmetic knows neither pessimism nor optimism, neither lack of faith nor capitulation. Figures are figures. If you examine the control figures of Gosplan, you will find that these figures show the disproportion-or, more exactly expressed, the shortage of industrial goods-to have reached the amount of 380 million rubles last year, while this year the figure will be 500 million, that is, the initial Gosplan figures show the disproportion to have increased by 25 percent. Comrade Rykov states in his theses that we might hope (merely hope) that the disproportion will not increase this year. What was the basis for this “hope”? The fact that the harvest is not so favorable as we all expected. Were I to follow in the false tracks of our critics, I might say that Comrade Rykov’s theses welcome the fact that the unfavorable conditions prevailing at harvest time reduced the otherwise respectable yield; and he welcomes this because, had the harvest been greater, the result would have been a greater disproportion. [Comrade Rykov: “I am of a different opinion.”] The figures speak for themselves. [A voice: “Why didn’t you speak in the discussion on Comrade Rykov’s report?”] Comrade Kamenev has here told you why we did not. Because I could not have added anything to this special economic report, in the form of amendments or arguments, that we had not brought forward at the April plenum. The amendments and other proposals submitted by me and other comrades to the April plenum remain in full force today. But the economic experience gained since April is obviously too small to give us room for hope that at the present stage the comrades present at this conference will be convinced. To bring up these points of contention again, before the actual course of economic life has tested them, would create unnecessary tensions. These questions will inevitably be more acceptable to the party when they can be answered by the statistics based on the latest experience; for objective economic experience does not decide whether figures are optimistic or pessimistic, but solely whether they are right or wrong. I believe our standpoint on the disproportion has been right.

We have disagreed on the rate of our industrialization, and I have been among those comrades who have pointed out that the present rate is insufficient, and that precisely this insufficient speed in industrialization imparts the greatest importance to the differentiation process going on in the villages. To be sure, there is not as yet anything disastrous in the fact that the kulak has raised his head or-this is the other side of the same coin-that the relative weight of the poor peasant in the village has declined. These are some of the serious problems that accompany the period of transition. They are unhealthy signs. There is no reason to “panic” of course. But they are phenomena which must be correctly assessed. And I have been among those comrades who have maintained that the process of differentiation in the village may assume a dangerous form if industry lags behind, that is, if the disproportion increases. The Opposition maintains that it is our duty to lessen the disproportion year by year. I see nothing Social Democratic in this.

We have insisted that the differentiation in the village demands a more elastic taxation policy with respect to the various strata of the peasantry, a reduction of taxation for the poorer middle strata of the peasantry, increased taxation for the well-to-do middle strata, and energetic pressure upon the kulak, especially in his relations to trading capital.

We have proposed that 40 percent of the poor peasantry should be freed from taxation altogether. Are we right or not? I believe that we are right; you believe we are wrong. But what is “Social Democratic” about this is a mystery to me. [Laughter.]

We have asserted that the increasing differentiation among the peasantry, taking place under the conditions imposed by the backwardness of our industry, brings with it the necessity for double safeguards in the field of politics, that is, we cannot take a tolerant attitude toward the extension of the franchise with respect to the kulak, the employer, and the exploiter, even if they operate only on a small scale. We raised the alarm when the famous electoral instructions extended the voting rights of the petty bourgeoisie. Were we right or not? You consider that our alarm was “exaggerated.” Well, even assuming that it was, there is nothing Social Democratic about it.

We demanded and proposed that the course being taken by the agricultural cooperatives toward the “highly productive middle peasant,” under which name we generally find the kulak, should be severely condemned. We proposed that the “slight shift” (this term was used in the report to the Politburo) of the credit cooperatives toward the well-to-do peasantry should be condemned. I cannot comprehend, comrades, what you find “Social Democratic” in this.

There have been differences of opinion on the question of wages. In substance, these differences consist of our being of the opinion that at the present stage of development of our industry and economy, and at our present economic level, the wage question must not be settled on the assumption that the workers must first increase the productivity of labor, which will then raise the wages, but that the contrary must be the rule, that is, a rise in wages, however modest, must be the prerequisite for an increased productivity of labor. [A voice: “Where will we get the means?”] This may be right or it may not, but it is not “Social Democratic.” We have pointed out the connection between various well-known aspects of our inner-party life and the growth of bureaucratism. I believe there is nothing “Social Democratic” about this either.

We have further opposed an overestimation of the economic elements of the capitalist stabilization and the underestimation of its political elements. If we inquire, for instance: What does the economic stabilization consist of in England at the present time? then it appears that England is going to ruin, that its trade balance is adverse, that its foreign trade is shrinking, that its production is declining. This is the “economic stabilization” of England. But to whom is bourgeois England clinging? Not to Baldwin, not to Thomas, but to Purcell. Purcellism is the pseudonym of the present “stabilization” in England. We are therefore of the opinion that it is fundamentally wrong, in consideration of the working masses who carried out the general strike, to combine either directly or indirectly with Purcell. This is the reason that we have demanded the dissolution of the Anglo-Russian Committee. I see nothing “Social Democratic” in this.

We have insisted upon a fresh revision of our trade union statutes, upon which subject I reported to the CC: a revision of those statutes from which the word “Profintern” was struck out last year and replaced by the words “international alliance of trade unions,” which cannot mean anything other than “Amsterdam.” I am glad to say that this revision of last year’s revision has been accomplished, and the word “Profintern” has been reinserted in our trade union statutes. But why was our uneasiness on the subject “Social Democratic”? That, comrades, is something which I entirely fail to understand. [Laughter.]

I should like, as briefly as possible, to enumerate the main points of difference which have arisen of late. Our standpoint on the questions concerned has been that we have observed the dangers likely to threaten the class line of the party and of the workers’ state under the conditions imposed by a long continuance of the NEP, and our encirclement by interna tional capitalism. But these differences, and the standpoint adopted by us in the defense of our opinions, cannot be construed into a “Social Democratic deviation” by the most complicated logical or even scholastic methods.

THE CHARACTER OF OUR REVOLUTION.

That is why it was found necessary to leave these actual and serious differences, engendered by the present epoch of our economic and political development, and to go back into the past in order to construe differences in the conception of the “character of our revolution” in general-not in the present period of our revolution, not with regard to the present concrete tasks, but with regard to the character of the revolution in general, or as expressed in the theses, the revolution “in itself,” the revolution “in its substance.” When a German speaks of a thing “in itself,” he is using a metaphysical term placing the revolution outside of all connection with the real world around it; it is abstracted from yesterday and tomorrow, and regarded as an “essence” from which everything proceeds. Now, then, in regard to this “essence,” I have been found guilty, in the ninth year of our revolution, of having denied the socialist character of our revolution! No more and no less! I discovered this for the first time in this resolution itself. If the comrades find it necessary for some reason to construct a resolution on quotations from my writings-and the main portion of the resolution, pushing into the foreground the theory of original sin (“Trotskyism”), is built upon quotations from my writings between 1917 and 1922-then it would at least be advisable to select the essential from everything I have written on the character of our revolution.

You will excuse me, comrades, but it is no pleasure to have to set aside the actual subject and to retail where and when I wrote this or that. But this resolution, in trying to support the accusation of a “Social Democratic” deviation, refers to passages from my writings, and I am obliged to give the information. In 1922 I was commissioned by the party to write the book Terrorism and Communism against Kautsky, against the characterization of our revolution by Kautsky as a nonproletarian and nonsocialist revolution. A large number of editions of this book were distributed both at home and abroad by the Comintern. The book met with no hostile reception from the comrades most closely involved, including Vladimir Ilyich. This book is not quoted in the resolution.

In 1922 I was commissioned by the Political Bureau to write the book entitled Between Imperialism and Revolution. In this book I utilized the special experience gained in Georgia, in the form of a refutation of the standpoint of those international Social Democrats who were using the Georgian uprising as material against us, for the purpose of subjecting to a fresh examination the main questions of the proletarian revolution, which has a right to tear down not only pettybourgeois prejudices but also petty-bourgeois institutions. Again, this book is not quoted.

At the Third Congress of the Comintern I gave a report, on behalf of the CC, declaring in substance that we had entered an era of unstable balance. I polemicized against Comrade Bukharin, who at that time was of the opinion that we were going to go through an uninterrupted series of revolutions and crises until the victory of socialism throughout the world, and that there would not and could not be any “stabilization.” At the time Comrade Bukharin accused me of a right deviation (perhaps Social Democratic too?). In full agreement with Lenin at the Third Congress I defended the theses which I had formulated. The import of the theses was that we, despite the slower speed of the revolution, would pass successfully through this period by developing the socialist elements in our economy.

At the Fourth World Congress in 1922 I was commissioned by the CC to follow Lenin with a report on the NEP. What was my theme? I argued that the NEP merely signifies a change in the forms and methods of socialist development. And now, instead of taking these works of mine, which may have been good or bad, but were at least fundamental, and in which, on behalf of the party, I defined the character of our revolution in the years between 1920 and 1923, you seize upon a few little passages, each only two or three lines, out of a preface and a postscript written at the same period.

I repeat that none of the passages quoted is from a fundamental work. These four little quotations (1917 to 1922) form the sole foundation for the accusation that I deny the socialist character of our revolution. The structure of the accusation thus being completed, every imaginable original sin is added to it, even the sin of the Opposition of 1925. The demand for a more rapid industrialization and the proposal to increase the taxation of the kulaks all arise from these four passages. [A voice: “Don’t form factions!”]

Comrades, I regret having to take your time, but I must quote a few more passages-I could cite hundreds-to refute everything that the resolution ascribes to me. First of all I must draw your attention to the fact that the four quotations upon which the theory of my original sin is based have all been taken from writings of mine between 1917 and 1922. Everything that I have said since appears to have been swept away by the wind. Nobody knows whether I subsequently regarded our revolution as socialist or not. Today, at the end of 1926, the present standpoint of the so-called Opposition on the main questions of economics and politics is sought in passages from my personal writings between 1917 and 1922, and not even in passages from my chief works, but in works written for some quite chance occasion. I shall return to these quotations and respond on every one of them. But first permit me to cite some quotations of a more essential character, written at the same period.

“We have reorganized our economic policy in anticipation of a slower development of our economy. We reckon with the possibility that the revolution in Europe, though developing and growing, is developing more slowly than we expected. The bourgeoisie has proved more tenacious. Even in our own country we are obliged to reckon with a slower transition to socialism, for we are surrounded by capitalist countries. We must concentrate our forces on the largest and best equipped undertakings. At the same time, we must not forget that the taxation in kind among the peasantry, and the increase of leased undertakings, form a basis for the development of commodity production, for the accumulation of capital, and for the rise of a new bourgeoisie. At the same time, the socialist economy will be built up on the narrower but firmer basis of big industry.”

For instance, the following is an excerpt from my speech at the conference of the Moscow Trade Union Council on October 28, 1921, after the introduction of the NEP:

At a membership meeting of our party on November 10 of the same year, in the Moscow district of Sokolniki, I stated: “What do we have now? We now have the process of socialist revolution, in the first place within a single state and in the second place in a state which is very backward, both economically and culturally, and surrounded on all sides by capitalist countries.”

What conclusion did I draw from this? Did I propose capitulation? I proposed the following:

“It is our task to make socialism prove its advantages. The peasant will be the judge who pronounces on the advantages or drawbacks of the socialist state. We are competing with capitalism in the peasant market….

“What is the present basis for our conviction that we shall be victorious? There are many reasons justifying our belief. These lie both in the international situation and in the development of the Communist Party; in the fact that we retain full power in our hands, and in the fact that we permit free trade solely within the limits which we deem necessary.”

This, comrades, was said in 1921, and not in 1926!

In my report at the Fourth World Congress (directed against Otto Bauer, to whom my relationship has now been discovered) I spoke as follows:

“Our most important weapon in the economic struggle occurring on the basis of the market is state power. Reformist simpletons are the only ones who are incapable of grasping the significance of this weapon. The bourgeoisie understands it excellently. The whole history of the bourgeoisie proves it.

“Another weapon of the proletariat is that the country’s most important productive forces are in its hands: the entire railway system, the entire mining industry, the overwhelming majority of enterprises servicing industry are under the direct economic management of the working class.

“The workers’ state likewise owns the land, and the peasants annually contribute in return for using it hundreds of mil lions of poods in taxes in kind.

“The workers’ power holds the state frontiers: foreign commodities, and foreign capital generally, can gain access to our country only within limits which are deemed desirable and legitimate by the workers’ state.

“Such are the weapons and means of socialist construction”

In a booklet published by me in 1923 under the title Problems of Everyday Life, you may read on this subject: “Now, what has the working class actually gained and secured for itself as a result of the revolution?

“1. The dictatorship of the proletariat (represented by the workers’ and peasants’ government under the leadership of the Communist Party).

“2. The Red Army-a firm support of the dictatorship of the proletariat.

“3. The nationalization of the chief means of production, without which the dictatorship of the proletariat would have become a form void of substance.

“4. The monopoly of foreign trade, which is the necessary condition of socialist state structure in a capitalist environment.

“These four things, definitely won, form the steel frame of all our work; and every success we achieve in economics or culture-provided it is a real achievement and not a sham-becomes in this framework a necessary part of the socialist structure.”

This same booklet contains another and even more definite formulation:

“The easier it was (comparatively, of course) for the Russian proletariat to pass through the revolutionary crisis, the harder its work of socialist construction now becomes. But, on the other hand, the framework of our new social structure, marked by the four characteristics mentioned above, gives an objectively socialist content to all conscientious and rationally directed efforts in the domain of economics and culture. Under the bourgeois regime the workman, with no desire or intention on his part, was continually enriching the bourgeoisie, and did it all the more, the better his work was. In the Soviet state a conscientious and good worker, whether he cares to do it or not (in case he is not in the party and keeps away from politics) achieves socialist results and increases the wealth of the working class. This is the doing of the October Revolution, and the NEP has not changed anything in this respect”

TOWARDS CAPITALISM OR SOCIALISM

I could prolong this chain of quotations indefinitely, for I never did and never could characterize our revolution differently. I shall confine myself, however, to one more passage, from a book quoted by Comrade Stalin (Toward Capitalism or Socialism?). This book was published for the first time in 1925 and was printed originally as a series in Pravda. The editors of our central paper have never drawn my attention to any heresies in this book with respect to the character of our revolution. This year the second edition of the book was issued. It has been translated into different languages by the Comintern and this is the first time I’ve heard that it gives a false idea of our economic development. Comrade Stalin has read you a few lines, picked out arbitrarily in order to show that this is “unclearly formulated.” I am thus obliged to read a somewhat longer passage, in order to prove that the idea in question is quite clearly formulated. The following is stated in the introduction, devoted to a criticism of our bourgeois and Social Democratic critics, above all, Kautsky and Otto Bauer. Here you may read:

“These judgments”- formed by the enemies of our economic methods- “are of two kinds. In the first place, we are told that we are ruining the country by our work of socialist construction; in the second place, we are told that our development of the productive forces is in reality carrying us toward capitalism.

“Criticism of the first type is characteristic of the mode of thought of the bourgeoisie. The second style of criticism is rather that of social democracy, i.e., bourgeois thought in a socialist disguise. It would be hard to draw a sharp line between the two styles of criticism, and frequently the two exchange their arsenal of arguments in a neighborly manner, without noticing it themselves, intoxicated as they are with the sacred war against communist barbarism.

“The present book, I hope, will prove to the unprejudiced reader that both camps are lying, not only the outright big bourgeoisie, but also the petty bourgeoisie who pretend to be socialist. They lie when they say that the Bolsheviks have ruined Russia. Indisputable facts prove that in Russia-disorganized by imperialist and civil wars-the productive forces in industry and agriculture are approaching the prewar level, which will be reached during the coming year. It is a false hood to state that the evolution of the productive forces is proceeding in the direction of capitalism. In industry, transportation, communications, commerce, finance, and credit operations, the part played by the nationalized economy is not lessened with the growth of the productive forces; on the contrary, this role is assuming increasing importance in the total economy of the country. Facts and figures prove this beyond dispute.

“The matter is much more complicated in the field of agriculture. No Marxist will be surprised by this; the transition from scattered single peasant establishments to a socialist system of land cultivation is inconceivable except after passing through a number of stages in technology, economics, and culture. The fundamental condition for this transition is the retention of power in the hands of the class whose object is to lead society to socialism (and which is becoming ever more able to influence the peasant population by means of state industry and by raising agricultural technology to a higher level and thus creating the prerequisites for a collectivization of agriculture)”

The draft of the resolution on the Opposition states that Trotsky’s standpoint closely approaches that of Otto Bauer, who has said, “In Russia, where the proletariat represents only a small minority of the nation, the proletariat can only maintain its rule temporarily, and is bound to lose it again as soon as the peasant majority of the nation has become culturally mature enough to take over the rule itself.”

In the first place, comrades, who could entertain the idea that so absurd a formulation could occur to any one of us? Whatever is to be understood by “as soon as the peasant majority of the nation has become culturally mature enough”? What does this mean? What are we to understand by “culture”? Under capitalist conditions the peasantry has no independent culture. As far as culture is concerned, the peasantry may mature under the influence of the proletariat or of the bourgeoisie. These are the only two possibilities existing for the cultural advance of the peasantry. To a Marxist, the idea that the “culturally matured” peasantry, having overthrown the proletariat, could take over power on its own account, is a wildly prejudiced absurdity. The experience of two revolutions has taught us that the peasantry, should it come into conflict with the proletariat and overthrow the proletarian power, simply forms a bridge-through Bonapartism-for the bourgeoisie. An independent peasant state founded on neither proletarian nor bourgeois culture is impossible. This whole construction of Otto Bauer’s collapses into a lamentable petty-bourgeois absurdity.

We are told that we have no faith in the establishment of socialism. And at the same time we are accused of wanting to “rob” the peasantry (not the kulaks, but the peasantry!).

I think, comrades, that these are not words out of our dictionary at all. The Communists cannot propose that the workers’ state “rob” the peasantry, and it is precisely with the peasantry that we are concerned. A proposal to free 40 percent of the poor peasantry from all taxation, and to lay these taxes upon the kulak, may be right or it may be wrong, but it can never be interpreted as a proposal to “rob” the peasantry.

I ask you: If we have no faith in the establishment of socialism in our country, or if (as is said of me) we propose that the European revolution be passively awaited, then why do we propose to “rob” the peasantry? To what end? That is incomprehensible. We are of the opinion that industrialization-the basis of socialism-is proceeding too slowly, and that this negatively affects the peasantry. If, let us say, the quantity of agricultural products put upon the market this year is 20 percent more than last-I take these figures with a reservation-and at the same time the grain price has sunk by 8 percent and the prices of various industrial products have risen by 16 percent, as has been the case, then the peasant gains less than when his crops are poorer and the retail prices for industrial products lower. The acceleration of industrialization, especially through increased taxation of the kulak, will result in the production of a larger quantity of goods, reducing the retail prices, to the advantage of the workers and of the greater part of the peasantry.

It is possible that you do not agree with this. But nobody can deny that it is a system of views on the development of our economy. How can you claim that we have no faith in the possibility of socialist development, and yet at the same time assert that we demand the robbing of the peasant? With what object? For what purpose? Nobody can explain this. I contend that it cannot be explained. There are things that are impossible to explain. For example, I have often asked myself why the dissolution of the Anglo-Russian Committee can be supposed to imply a call to leave the trade unions? And why does the nonentry into the Amsterdam International not constitute an appeal to the workers not to join the Amsterdam trade unions? [A voice: “That will be explained to you!”] I have never received an answer to this question, and never will. [A voice: “You will get your answer.”] Neither shall I receive a reply to the question of how we contrive to disbelieve in the realization of socialism and yet endeavor to “rob” the peasantry.

The book of mine from which I last quoted speaks in detail of the importance of the correct distribution of our national income, since our economic development is proceeding amidst the struggle of two tendencies: the socialist and the capitalist ones.

“…The outcome of the struggle depends on the speed of development of each of these tendencies. In other words if state industry develops more slowly than agriculture; if the latter should proceed to produce with increasing speed the two extreme poles mentioned above (capitalist farmers above, proletarians below); this process would, of course, lead to a restoration of capitalism.

“But just let our enemies try to prove the inevitability of this prospect. Even if they approach this task more intelligently than poor Kautsky (or MacDonald), they will burn their fingers. On the other hand, is such a possibility entirely precluded? Theoretically, it is not. If the dominant party were guilty of one mistake after another, in politics as well as in economics; if it were thus to retard the growth of industry, which is now developing so promisingly; if it were to relinquish its control over the political and economic processes in the village; then, of course, the cause of socialism would be lost in our country. But we are not at all obliged to make any such assumptions in our prognosis.

“How power is lost, how the achievements of the proletariat may be surrendered, how one may work for capitalism-all this has been brilliantly demonstrated to the international proletariat by Kautsky and his friends, after November 9, 1918. Nothing needs to be added to this lesson.

“Our tasks, our goals, our methods, are different. We want to show how power, once achieved, may be retained and consolidated, and how the form of the proletarian state may be filled with the economic content of socialism”

The whole content of this book [A voice: “There is nothing about the cooperatives in it!”]-I shall come to the co operatives-the whole content of this book is devoted to the subject of how the proletarian form of state is to be given the economic content of socialism. It may be said (insinuations have already been made in this direction): Yes, you believed that we were moving toward socialism so long as the process of reconstruction was going on, and so long as industry developed at a speed of 45 or 35 percent per year, but now that we have arrived at a crisis in regard to fixed capital and you see the difficulties of expanding our fixed capital, you have been seized with a so-called “panic.”

I cannot quote the whole of the chapter on “Material Limits and Possibilities of the Rate of Development.” It points out the four elements characterizing the advantages of our system over capitalism and draws the following conclusion:

“Considered together, these four advantages, if rightly utilized, will enable us in the next few years to increase the coefficient of our industrial expansion not only to twice the figure of 6 percent attained in the prewar period, but to three times that figure, and perhaps to even more”

If I am not mistaken, the coefficient of our industrial growth will amount, according to the plans, to 18 percent. In this there are, of course, still reconstruction elements. But in any case the extremely rough statistical prognosis which I made as an example eighteen months ago coincides fairly well with our actual speed this year.

IS THIS TROTZKYISM?

You ask: What is the explanation of those frightful passages quoted in the resolution? I shall have to answer this question. I must first, however, repeat that not a single word has been quoted from the fundamental works which I wrote on the character of the revolution between 1917 and 1922, and complete silence is preserved on everything that I have written since 1922, even on that written last year and this year. Four passages are quoted. Comrade Stalin has dealt with them in detail, and they are referred to in the resolution, so you will permit me to devote some words to them as well.

“The working-class movement achieves victory in the democratic revolution. The bourgeoisie become counterrevolutionary. Among the peasantry, the whole of the well-to-do section, and a fairly large part of the middle peasantry, also grow ‘wiser,’ quieten down and turn to the side of the counterrevolution in order to wrest power from the proletariat and the rural poor. This struggle would have been almost hopeless for the Russian proletariat alone and its defeat would have been… inevitable…had the European socialist proletariat not come to the assistance of the Russian proletariat”

I am afraid, comrades, that if anyone told you that these lines represented a malicious product of Trotskyism, many comrades would believe it. But this passage is Lenin’s. The fifth volume of the Lenin Miscellany contains a draft of a pamphlet which Lenin intended to write at the end of 1905. Here this possible situation is described: The workers are victorious in the democratic revolution, the well-to-do section of the peasantry goes over to counterrevolution. I should say that this passage is quoted in the latest issue of Bolshevik, on page 68, but unfortunately with a grave misrepresentation, although the excerpt is given in quotation marks: the words referring to the considerable section of the middle peasantry are simply left out. I call upon you to compare the fifth Lenin Miscellany, page 451, with the latest issue of Bolshevik, page 68.

I could quote dozens of such passages from Lenin’s works: vol. 9, pp. 135-36; vol. 10, p. 191; vol. 12, pp. 106-07. (I don’t have the time to read them, but anyone may look up the references for himself.) I shall quote only one passage, from vol. 10, p. 280:

“The Russian revolution”- he is referring to the democratic revolution-” can achieve victory by its own efforts, but it cannot possibly hold and consolidate its gains by its own strength. It cannot do this unless there is a socialist revolution in the West. Without this condition restoration is inevitable, whether we have municipalization, or nationalization, or division of the land: for under each and every form of property or ownership the small proprietor will always be a bulwark of restoration. After the complete victory of the democratic revolution the small proprietor will inevitably turn against the proletariat.”

[A voice: “We have introduced the NEP.”]

True, I shall refer to that presently.

Let us now turn to that passage which I wrote in 1922, in order that we may see how my standpoint on the revolution in the epoch of 1904-05 had developed.

I have no intention, comrades, of raising the question of the theory of permanent revolution. This theory- in respect both to what has been right in it and to what has been incomplete and wrong-has nothing whatever to do with our present contentions. In any case, this theory of permanent revolution, to which so much attention has been devoted recently, is not the responsibility in the slightest degree of either the Opposition of 1925 or the Opposition of 1923, and even I myself regard it as a question which has long been consigned to the archives.

But let us return to the passage quoted in the resolution. (This I wrote in 1922, but from the standpoint of 1905-06.)

“The proletariat, once having power in its hands…would enter into hostile conflict, not only with all those bourgeois groups which had supported it during the first stages of its revolutionary struggle, but also with the broad masses of the peasantry, with whose collaboration it-the proletariat-had come into power.”

Although this was written in 1922, it was put in the future tense-the proletariat would come into conflict with the bourgeoisie, etc.-because prerevolutionary views were being described. I ask you: Has Lenin’s prognosis of 1905-06, that the middle peasants would go over to counterrevolution to a great extent, proved true? I maintained that it has proved true in part. [Voices: “In part? When?” Disturbance.] Yes, under the leadership of the party and above all under Lenin’s leadership, the division between us and the peasantry was bridged over by the New Economic Policy. This is indisputable. [Disturbance.] If any of you imagine, comrades, that in 1926 I do not grasp the meaning of the New Economic Policy, you are mistaken. I grasp the meaning of the New Economic Policy in 1926, perhaps not so well as other comrades, but still I grasp it. But you must remember that at that time, before there was any New Economic Policy, before there had been a revolution of 1917, and we were sketching the first outlines of possible developments, utilizing the experience won in previous revolutions-the Great French Revolution and the revolution of 1848-at that time all Marxists, not omitting Lenin (I have given quotations), were of the opinion that after the democratic revolution was completed and the land given to the peasantry, the proletariat would encounter opposition not only from the big peasants, but from a considerable section of the middle peasants, who would represent a hostile and even counterrevolutionary force.

Have there been signs among us of the truth of this prognosis? Yes, there have been signs, and fairly distinct ones. For instance, when the Makhno movement in the Ukraine helped the White Guards to sweep away the Soviet power this was one proof of the correctness of Lenin’s prognosis. The Antonov rising, the rising in Siberia, the rising on the Volga, the rising in the Urals, the Kronstadt revolt, when the “middle peasants” conversed with Soviet power in the language of twelve-inch naval guns- doesn’t all this prove that Lenin’s forecast was correct at a certain stage of development in the revolution? [Comrade Moiseyenko: ”And what did you propose?”] Is it not perfectly clear that the passage written by me in 1922 on the division between us and the peasantry was simply a statement of these facts?

We bridged over the schism between us and the peasantry by means of the NEP. And were there differences between us during the transition to the NEP? There were no differences during the transition to the NEP. [Disturbance.] There were differences over the trade union question before the transition to the NEP, when the party was still seeking a way out of the blind alley. These differences were of serious importance. But on the question of the NEP, when Lenin submitted the NEP resolution to the Tenth Party Congress, we all voted unanimously for it. And when a new trade union resolution arose as a result of the New Economic Policy- a few months after the Tenth Party Congress-we again voted unanimously for this resolution in the CC. But during the period of transition-and the change wrought by it was no small one-the peasants, including the middle peasants, declared: “We are for the Bolsheviks, but against the Communists.” What does this mean? It means a peculiarly Russian form of desertion from the proletarian revolution on the part of the middle peasantry at a given stage.

I am reproached with having said that it is “hopeless to think that revolutionary Russia would be able to maintain itself in the face of conservative Europe” This I wrote in May 1917, and I believe that it was perfectly right. Have we maintained ourselves against a conservative Europe? Let us consider the facts. At the moment when Germany was discussing a peace treaty with the Entente, the danger was especially great. Had the German revolution not broken out at this point-that German revolution which remained uncompleted, suffocated by the Social Democrats, yet still sufficing to overthrow the old regime and to demoralize the Hohenzollern army-I repeat, had the German revolution, such as it was, not broken out, then we should have been overthrown. It is not by accident that the passage contains the phrase “in opposition to a conservative Europe,” and not “in opposition to a capitalist Europe.” Against a conservative Europe, maintaining its whole apparatus, and in particular its armies. I ask you: Could we maintain ourselves under these circumstances, or could we not? [A voice: “Are you talking to children?”] That we still continue to exist is due to the fact that Europe has not remained what it was. Lenin wrote as follows on this subject:

“We are living not merely in a state, but in a system of states, and it is inconceivable for the Soviet Republic to exist alongside of the imperialist states for any length of time. One or the other must triumph in the end”

When did Lenin say this? On March 18, 1919, that is two years after the October Revolution. My words of 1917 signified that if our revolution did not shake Europe, did not move it, then we were lost. ls this not in substance the same? I ask all the older comrades, who were politically conscious before and during 1917: What was your conception of the revolution and its consequences?

When I try to recollect this, I can find no other formulation than approximately the following:

“We thought: either the international revolution comes to our assistance, and in that case our victory will be fully assured, or we shall do our modest revolutionary work in the conviction that even in the event of defeat we shall have served the cause of the revolution and that our experience will benefit other revolutions. It was clear to us that without the support of the international world revolution the victory of the proletarian revolution was impossible. Before the revolution, and even after it, we thought: either revolution breaks out in other countries, in the capitalistically more developed countries, immediately, or at least very quickly, or we must perish”

This was our conception of the fate of the revolution. Who said this? [Comrade Moiseyenko: “Lenin!” A voice: “And what did he say later on?”]

Lenin said this in 1921, while the passage quoted from me dates from 1917. I have thus a right to refer to what Lenin said in 1921. [A voice: “And what did Lenin say later on?”] Later on I too said something different. [Laughter.] Both before the revolution, and after it, we believed that:

“Either revolution breaks out in the other countries, in the capitalistically more developed countries, immediately, or at least very quickly, or we must perish.”

But:

“In spite of this conviction, we did all we possibly could to preserve the Soviet system under all circumstances, come what may, because we knew that we were not only working for ourselves, but also for the international revolution. We knew this, we repeatedly expressed this conviction before the October Revolution, immediately after it, and at the time we signed the Brest-Litovsk Peace Treaty. And, generally speaking, this was correct”

This passage goes on to say that our path has become more intricate and winding, but that in all essentials our prognosis was correct. As I have already said, we went over to the NEP unanimously, without any differences whatever. [Comrade Moiseyenko: “To save us from utter ruin!”]

True, just for that reason, to save us from utter ruin.

Comrades, I beg you to extend the time allotted for my speech. I should like to speak on the theory of socialism in one country. I ask for another half hour. [Disturbance.]

Comrades, on the question of the relations between the proletariat and the peasantry…

CHAIRMAN: Please wait till we have decided. I submit three proposals; firstly, to adhere to the original time allotted to Comrade Trotsky; secondly, an extension of half an hour; thirdly, an extension of a quarter of an hour. [On a vote being taken there is a majority for the half-hour extension.]

END OF PART ONE.

International Press Correspondence, widely known as”Inprecorr” was published by the Executive Committee of the Communist International (ECCI) regularly in German and English, occasionally in many other languages, beginning in 1921 and lasting in English until 1938. Inprecorr’s role was to supply translated articles to the English-speaking press of the International from the Comintern’s different sections, as well as news and statements from the ECCI. Many ‘Daily Worker’ and ‘Communist’ articles originated in Inprecorr, and it also published articles by American comrades for use in other countries. It was published at least weekly, and often thrice weekly. The ECCI also published the magazine ‘Communist International’ edited by Zinoviev and Karl Radek from 1919 until 1926 monthly in German, French, Russian, and English. Unlike, Inprecorr, CI contained long-form articles by the leading figures of the International as well as proceedings, statements, and notices of the Comintern. No complete run of Communist International is available in English. Both were largely published outside of Soviet territory, with Communist International printed in London, to facilitate distribution and both were major contributors to the Communist press in the U.S. Communist International and Inprecorr are an invaluable English-language source on the history of the Communist International and its sections.

PDF of full issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/international/comintern/inprecor/1926/v06n79-nov-25-1926-inprecor.pdf