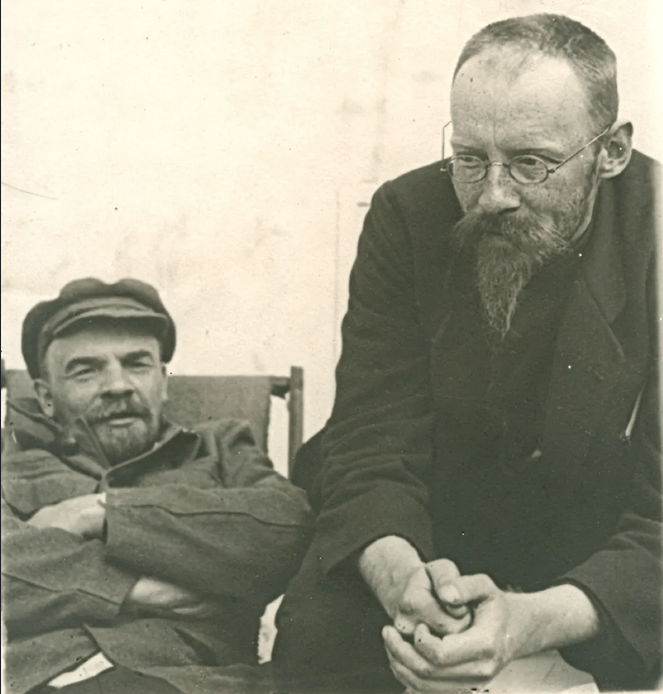

Transcribed online for the first time here is Trotsky’s full final speech as a delegate to a meeting of the Communist Part,y his last internal oppositionist fight, and important record of that most consequential of schisms on the Communist movement. The extensive address was recorded verbatim, interruptions, cat calls, and all. The Conference took place in October-November, 1926, focused on combating the United Opposition’s challenge, the assessment of the NEP, and international situation. The United Opposition formed in 1926 after the Bukharin-Stalin faction defeated the ‘New Opposition’ led by of Zinoviev and Kamaenv in 1925. Along with those New Oppositionists based in Leningrad, forces of the old Workers Opposition, along with the variations within Trotsky’s Left Opposition, joined together in a struggle against the Stalin-Bukharin Bloc and the increasingly divisive N.E.P. at the upcoming 15th Conference of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union.

Leading party figures, such as Lenin’s widow Natalia Krupskaya and A.G. Shlyapnikov, as well as thirteen members of the Politburo, Central Committee, and the Central Control Commission, N.I. Muralov, G..E. Evdokimov, H.G. Rakovsky, G.L. Pyatakov, I.T. Smilga, G.E. Zinoviev, L.D. Trotsky, L.B. Kamenev, A.A. Peterson, I.P. Bakaev, K.S. Solovyov, G.Ya. Lizdin, and P.N. Avdeev signed the declaration. With international policy, relations to the peasantry, prohibition, industrialization, bureaucracy, ‘socialism in one country,’ the legacy of Lenin, and most of all how to move beyond the New Economic Policy were fiercely contentious. The results was a route, with Kamanev, Zinoviev, and Trotsky removed from the Politburo (along with Stalin, Trotsky was the only consistent member of that body since the Revolution). Zinoviev would also be removed from his Comintern leadership. Though retaining positions on the Central Committee, Trotsky, Zinoviev and many other oppositionists would be expelled from the the following 15th Congress (not to be confused with the 15th Conference in late 1927. Because of the length, this speech will be posted in two parts.

‘Speech to the 15th Congress of the Russian Communist Party: Part Two’ by Leon Trotsky from International Press Correspondence. Vol. 6 No. 79. November 25, 1926.

RELATIONS TO THE PEASANTRY

TROTSKY: The next passage quoted from my writings has brought me the reproach that whereas Lenin said “ten to twenty years of correct relations with the peasantry, and our victory is assured on an international scale,” Trotskyism, on the contrary, assumes that the proletariat cannot enter into any correct relations with the peasantry until the world revolution has been accomplished. First of all I must ask the actual meaning of the passage quoted. Lenin speaks of ten to twenty years of correct relations with the peasantry. This means that Lenin did not expect socialism to be established within ten to twenty years. Why? Because under socialism we must understand a state of society in which there is neither proletariat nor peasantry, nor any classes whatever. Socialism abolishes the opposition between town and country. Thus the term of twenty years is set before us, in the course of which we must pursue a political line leading to correct relations between the proletariat and the peasantry. That is the first point.

It is said that Trotskyism is of the opinion that there can be no correct relations between the proletariat and the peasantry until the world revolution has been accomplished. I am thus alleged to have laid down a law according to which incorrect relations must be maintained with the peasantry as far as possible, until the international revolution has been victorious. [Laughter.] Apparently it was not intended to express this idea here, as there is no sense in it whatever.

What was the NEP? The NEP has been a process of shunt ing onto a new track, precisely for the establishment of correct relations between the proletariat and the peasantry. Were there differences between us on this subject? No, there were none. What we are arguing about now is the taxation of the kulak, and the forms and methods to be adopted in allying the proletariat with the village poor. What is the actual matter at hand? The best method of establishing correct relations between the peasantry and the proletariat. You have the right to disagree with individual proposals of ours, but you must recognize that the whole ideological struggle revolves around the question of what relations are correct at the present stage of development.

Were there differences between us in 1917 on the peasant question? No. The peasant decree, the “Social Revolutionary” peasant decree, was adopted unanimously by us as our basis. The land decree, drawn up by Lenin, was accepted by us unanimously and gave rise to no differences in our circles. Did the policy of “de-kulakization” afford any cause for differences? No, there were no differences on this. [A voice: ”And Brest?”] Did the struggle commenced by Lenin, for winning over the middle peasantry, give rise to differences? No, it gave rise to none. I do not assert that there were no differences whatever, but I definitely maintain that however great the differences of opinion may have been in various and even important questions, there were no differences of opinion in the matter of the main line of policy to be pursued with regard to the peasantry.

In 1919 there were rumors abroad of differences on this question. And what did Lenin write on the subject? Let us look back. I was asked at that time by the peasant Gulov: “What are the differences of opinion between you and Ilyich?” and I replied to this question both in Pravda and in Izvestia. Lenin wrote as follows on the matter, both in Pravda and in Izvestia, in February 1919:

“Izvestia of February 2 carried a letter from a peasant, G. Gulov, who asks a question about the attitude of our workers’ and peasants’ government to the middle peasantry, and tells of rumors that Lenin and Trotsky are not getting on together, and that there are big differences between them on this very question of the middle peasant.

“Comrade Trotsky has already replied to that in his “Letter to the Middle Peasants,” which appeared in Izvestia of February 7. In this letter Comrade Trotsky says that the rumors of differences between him and myself are the most monstrous and shameless lie, spread by the landowners and capitalists, or by their witting and unwitting accomplices. For my part, I entirely confirm Comrade Trotsky’s statement. There are no differences between us, and as regards the middle peasants there are no differences either between Trotsky and myself, or in general in the Communist Party, of which we are both members. In his letter Comrade Trotsky has explained clearly and in detail why the Communist Party and present workers’ and peasants’ government, elected by the soviets and composed of members of that party, do not consider the middle peas ants to be their enemies. I fully subscribe to what Comrade Trotsky has said.”

This was before the NEP. Then came the transition to the NEP. I repeat once more that the transition to the NEP gave rise to no differences. On the NEP question I gave a report before the Fourth World Congress, in the course of which I polemicized against Otto Bauer. Later I wrote as follows:

“The NEP is regarded by the bourgeoisie and the Mensheviks as a necessary (but of course ‘insufficient’) step toward freeing the productive forces from ‘enslavement.’ The Menshevik theoreticians of both the Kaut sky and the Otto Bauer variety have welcomed the NEP as the dawn of capitalist restoration in Russia. They add: Either the NEP will destroy the Bolshevik dictatorship (favorable result) or the Bolshevik dictatorship will destroy the NEP (regrettable result).”

The whole of my report at the Fourth World Congress went to prove that the NEP will not destroy the Bolshevik dictatorship, but that the Bolshevik dictatorship, under the conditions given by the NEP, will secure the supremacy of the socialist elements in the economy over the capitalists.

LENIN ON SOCIALISM IN ONE COUNTRY.

Another passage from my works has been brought up against me-and here I come to the question of the possibility of the victory of socialism in one country-which reads as follows:

“The contradictions between a workers’ government and an overwhelming majority of peasants in a backward country could be resolved only on an international scale, in the arena of a world proletarian revolution.”

This was said in 1922. The accusing resolution makes the following statement:

“The conference places on record that such views as these on the part of Comrade Trotsky and his followers, on the fundamental question of the character and prospects of our revolution, have nothing in common with the views of our party, with Leninism.”

If it had been stated that a shade of difference from the party’s position- although I do not find it so even today- or that these views had not yet been precisely formulated (I do not find this to be so either). But it is stated quite flatly: These views “have nothing in common with the views of our party, with Leninism.”

Here I must quote a few lines closely related to Leninism:

“The complete victory of the socialist revolution in one country alone is inconceivable and demands the most active cooperation of at least several advanced countries, which do not include Russia”.

It was not I who said this, but one greater than I. Lenin said this on November 8, 1918. Not before the October Revolution, but on November 8, 1918, one year after we had seized power. If he had said nothing else but this, we could easily infer what we liked from it by tearing one sentence or the other out of context. [A voice: “He was speaking of the final victory!”] No, pardon me, he said: “demands the most active cooperation.” Here it is impossible to sidetrack from the main question to the question of “intervention,” for it is plainly stated that the victory of socialism demands not merely protection against intervention-but the co operation of “at least several advanced countries, which do not include Russia.” [Voices: ”And what follows from that?”] This is not the only passage in which we see that not merely intervention is meant. And thus the conclusion to be drawn is the fact that the standpoint which I have de fended, to the effect that the internal contradictions arising out of the backwardness of our country must be solved by international revolution, is not my exclusive property, but that Lenin defended these same views, only incomparably more sharply and categorically.

We are told that this applied to the epoch in which the law of the uneven development of the capitalist countries is supposed to have been still unknown, that is, the epoch before imperialism. I cannot go thoroughly into this. But I must unfortunately place on record that Comrade Stalin commits a great theoretical and historical error here. The law of uneven development of capitalism is older than imperialism. Capitalism is developing very unevenly today in the various countries. But in the nineteenth century this unevenness was greater than in the twentieth. At that time England was lord of the world, while Japan on the other hand was a feudal state closely confined within its own limits. At the time when serfdom was abolished among us, Japan began to adapt itself to capitalist civilization. China was, however, still wrapped in the deepest slumber. And so forth. At that time the unevenness of capitalist development was greater than now. Those unevennesses were as well known to Marx and Engels as they are to us. Imperialism has developed a more “leveling tendency” than pre-imperialist capitalism, for the reason that finance capital is the most elastic form of capital. It is, however, indisputable that today, too, there are great unevennesses in development. But if it is maintained that in the nineteenth century, before imperialism, capital ism developed less unevenly, and the theory of the possibility of socialism in one country was therefore wrong at that time, while today, now that imperialism has increased the heterogeneity of development, the theory of socialism in one country has become correct, then this assertion contradicts all historical experience, and completely reverses fact. No, this will not do; other and more serious arguments must be sought.

Comrade Stalin has written:

“Those that those who deny the possibility of establishing socialism in one country must deny at the same time the justifiability of the October Revolution.”

But in 1918 we heard from Lenin that the establishment of socialism requires the direct cooperation of at least several advanced countries, “which do not include Russia.” Yet Lenin did not deny the justifiability of the October Revolution. And he wrote as follows regarding this in 1918:

“I know that there are, of course, wiseacres with a high opinion of themselves and even calling themselves socialists”- this was written against the adherents of Kautsky and Sukhanov-“who assert that power should not have been taken until the revolution broke out in all countries. They do not realize that in saying this they are deserting the revolution and going over to the side of the bourgeoisie. To wait until the working classes carry out a revolution on an international scale means that everyone will remain frozen in a state of anticipation. “This is nonsense.”

…I am sorry, but it goes on as follows-

“This is nonsense. Everyone knows the difficulties of a revolution …. Final victory is only possible on a world scale, and only by the joint efforts of the workers of all countries”

Despite this, Lenin did not deny the “justifiability” of the October Revolution.

And further. In 1921-not in 1914, but in 1921-Lenin wrote:

“Highly developed capitalist countries have a class of agricultural wage-workers that has taken shape over many decades…Only in countries where this class is sufficiently developed is it possible to pass directly from capitalism to socialism…”

Here it is not a question of intervention but of the level of economic development and of the development of the class relations of the country.

“We have stressed in a good many written works, in all our public utterances, and all our statements in the press, that this is not the case in Russia, for here industrial workers are a minority and small peasants are the vast majority. In such a country, the socialist revolution can triumph only on two conditions. First, if it is given timely support by a socialist revolution in one or several advanced countries….

“The second condition is agreement between the proletariat, which is exercising its dictatorship, that is, holds state power, and the majority of the peasant population ….

“We know that so long as there is no revolution in other countries, only agreement with the peasantry can save the socialist revolution in Russia. And that is how it must be stated, frankly, at all meetings and in the entire press” [from a speech to the Tenth Congress of the Russian Communist Party, in Collected Works, vol. 32, pp. 214-15].

Lenin did not state that the understanding with the peasantry sufficed, enabling us to build up socialism independent of the fate of the international proletariat. No, this under standing is only one of the conditions. The other condition is the support to be given the revolution by other countries. He combines these two conditions with each other, emphasizing their special necessity for us as we live in a backward country.

And finally, it is brought up against me that I have stated that “a real advance of socialist economics in Russia is possible only after the victory of the proletariat in the most important countries of Europe.” It is probable, comrades, that we have become inaccurate in the use of various terms. What do we mean by “socialist economics” in the strict sense of the term? We have great successes to record, and are naturally proud of these. I have endeavored to describe them in my booklet Toward Socialism or Capitalism? for the benefit of foreign comrades. But we must make a sober survey of the extent of these successes. Comrade Rykov’s theses state that we are approaching the prewar level. But this is not quite accurate. Is our population the same as before the war? No, it is larger. And the average per capita consumption of industrial goods is considerably less than in 1913. The Supreme Council of the National Economy calculates that in this respect we shall not regain the prewar level until 1930. And then, what was the level of 1913? It was the level of misery, of backwardness, of barbarism. If we speak of socialist economics, and of a real advance in socialist economics, we mean: no antagonism between town and country, general content, prosperity, culture. This is what we mean by the real advance of socialist economics. And we are still far indeed from this goal. We have destitute children, we have unemployed, from the villages there come three million superfluous workers every year, half a million of whom seek work in the cities, where the industries cannot absorb more than 100,000 yearly. We have a right to be proud of what we have achieved, but we must not distort the historical perspective. What we have accomplished is not yet a real advance of socialist economics, but only the first serious steps on that long bridge leading from capitalism to socialism. Is this the same thing? By no means. The passage quoted against me stated the truth.

In 1922 Lenin wrote:

“But we have not finished building even the foundations of socialist economy and the hostile powers of moribund capitalism can still deprive us of that. We must clearly appreciate this and frankly admit it; for there is nothing more dangerous than illusions (and vertigo, particularly at high altitudes). And there is absolutely nothing terrible, nothing that should give legitimate grounds for the slightest despondency, in admitting this bitter truth; for we have always urged and reiterated the elementary truth of Marxism-that the joint efforts of the workers of several advanced countries are needed for the victory of socialism” [Collected Works, vol. 33, p. 206; emphasis added by Trotsky].

The question here is therefore not of intervention, but of the joint efforts of several advanced countries for the establishment of socialism. Or was this written by Lenin before the epoch of imperialism, before the law of unequal development was known? No, he wrote this in 1922.

There is, however, another passage, in the article on cooperatives, one single passage, which is set up against everything else that Lenin wrote, or rather the attempt is made so to oppose it. [A voice: “Accidentally!”] Not by any means accidentally. I am in full agreement with the sentence. It must be understood properly. The passage is as follows:

“Indeed, the power of the state over all large-scale means of production, political power in the hands of the proletariat, the alliance of this proletariat with the many millions of small and very small peasants, the assured proletarian leadership of the peasantry, etc.-is that not all that is necessary to build a complete socialist society out of cooperatives, out of cooperatives alone, which we formerly ridiculed as huckstering and which from a certain aspect we have the right to treat as such now, under NEP? Is this not all that is necessary to build a complete socialist society? It is still not the building of socialist society, but it is all that is necessary and sufficient for it” [Collected Works, vol. 33, p. 468].

[A voice: “You read much too quickly.” Laughter.] Then you must give me a few minutes more, comrades. [Laughter. A voice: “Right!”] Right? I am agreed. [A voice: “That is just what we want.”]

What is the question here? What elements are here enumerated? In the first place, the possession of the means of production; in the second, the power of the proletariat; thirdly, the bond between the proletariat and the peasantry; fourthly, the proletarian leadership of the peasantry; and fifthly, thecooperatives. I ask you: does any one of you believe that socialism can be established in one single isolated country? Could perchance the proletariat in Bulgaria alone, if it had the peasantry behind it, seize power, build up the cooperatives and establish socialism? No, that would be impossible. Consequently further elements are required in addition to the above: the geographical situation, natural wealth, technology, culture. Lenin enumerates here the conditions of state power, property relations, and the organizational forms of the cooperatives. Nothing more. And he says that we, in order to establish socialism, need not proletarianize the peasantry, nor do we need any fresh revolutions, but that we are able, with power in our hands, in alliance with the peasantry, and with the aid of the cooperatives, to carry our task to completion through the agency of these state and social forms and methods.

But, comrades, we know another definition which Lenin gave of socialism. According to this definition, socialism is equal to Soviet power plus electrification. Is electrification canceled in the passage just quoted? No, it is not canceled. Everything which Lenin otherwise said about the establishment of socialism-and I have cited clear formulations above-is supplemented by this quotation, but not canceled. For electrification is not something to be carried out in a vacuum, but under certain conditions, under the conditions imposed by the world market and the world economy, which are very tangible facts. The world economy is not a mere theoretical generalization, but a definite and powerful reality, whose laws encompass us; a fact of which every year of our development convinces us.

THE NEW THEORY

Before dealing with this in detail, I should like to remind you of the following: Some of our comrades, before they created an entirely new theory, and in my opinion an entirely wrong one, based on a one-sided interpretation of Lenin’s article on the cooperatives, held quite a different standpoint. In 1924 Comrade Stalin did not say the same as he does today. This was pointed out at the Fourteenth Party Congress, but the passage quoted did not disappear on that account, but remains fully even in 1926.

Let us read: “Can this task be fulfilled, can the final victory of socialism be attained in a single country without the joint efforts of the proletariat in several advanced countries? No, it cannot. In order to overthrow the bourgeoisie, the efforts of a single country are sufficient; this is proved by the history of our revolution. For the final victory of socialism, for the organization of socialist production, the efforts of a single country, and particularly of such a peasant country as Russia, are inadequate; for that, the efforts of the proletariat of several advanced countries are required” [from the first edition of Foundations of Leninism, quoted by Stalin in Problems of Leninism, p. 61; emphasis added by Trotsky].

This was written by Stalin in 1924, but the resolution quotes me only up to 1922. [Laughter.] Yes, this is what was said in 1924: For the organization of socialist production not for protection against intervention, not as a guarantee against the restoration of the capitalist order, no, no-but for “the organization of socialist production,” the efforts of one single country, especially such an agrarian country as Russia, do not suffice. Comrade Stalin has given up this standpoint. He has of course a right to do so.

In his book, Problems of Leninism, he says:

“What is the defect in this formulation?

“The defect is that it links up two different questions. First there is the question of the possibility of completely constructing socialism by the efforts of a single country, which must be answered in the affirmative. Then there is the question: can a country, in which the dictatorship of the proletariat has been established, consider itself fully guaranteed against foreign intervention, and consequently against the restoration of the capitalist order number of other countries, a question which must be answered in the negative” [Problems of Leninism, p. 62].

But if you will allow me to say so, we do not find these two questions confused with one another in the first passage quoted, dating from 1924. Here it is not a question of intervention, but solely of the impossibility of the complete organization of completely socialized production by the unaided efforts of such a peasant country as Russia.

And truly, comrades, can the whole question be reduced to one of intervention? Can we simply imagine that we are establishing socialism here in this house, while the enemies outside in the street are throwing stones through the window panes? The matter is not so simple. Intervention is war, and war is a continuation of politics, but with other weapons. But politics are applied economics. Hence the whole question is one of the economic relations between the Soviet Union and the capitalist countries. These relations are not exhausted in that one form known as intervention. They possess a much more continuous and profound character. Comrade Bukharin has stated in so many words that the sole danger of intervention consists of the fact that in the event that no intervention comes:

“we can work toward socialism even on this wretched technical basis” (we can work toward it, that is true L.T.) “that this growth of socialism will be much slower, and we shall move forward at a snail’s pace; but all the same we shall work toward socialism, and we shall realize it” [at the Fourteenth Party Congress].

That we are working toward socialism is true. That we shall realize it hand in hand with the world proletariat is incontestable. [Laughter.] In my opinion it is out of place at a Communist conference to laugh when the realization of socialism hand in hand with the international proletariat is spoken of [Laughter. Voices: “No demagogy!” “You cannot catch us with that!”] But I tell you that we shall never realize socialism at a snail’s pace, for the world’s markets keep too sharp a control over us. [A voice: “You are quite alarmed!”] How does Comrade Bukharin imagine this realization? In his last article in Bolshevik, which I must say is the most scholastic work which has ever issued from Bukharin’s pen [Laughter.], he says:

“The question is whether we can work toward socialism, and establish it, if we abstract this from the international factors” [“On the Nature of Our Revolution and the Possibility of Successful Socialist Construction in the USSR,” Bolshevik, no. 19-20, 1926].

Just listen to this: “Whether we can work toward socialism, and establish it, if we abstract this question from the inter national factors.” If we accomplish this “abstraction,” then of course the rest is easy. But we cannot. That is the whole point. [Laughter.]

It is possible to walk naked in the streets of Moscow in January, if we can abstract ourselves from the weather and the police. [Laughter.] But I am afraid that this abstraction would fail, both with respect to weather and to police, were we to make the attempt. [Laughter.]

“We repeat once more: it is a question of internal forces and not of the dangers connected with the outside world. It is therefore a question of the character of the revolution” [Bukharin, in Bolshevik, no. 19-20, p. 54].

The character of our revolution, independent of international relations! Since when has this self-sufficing character of our revolution existed? I maintain that our revolution, as we know it, would not exist at all but for two international prerequisites: firstly, the factor of finance capital, which, in its greed, has fertilized our economic development; and secondly, Marxism, the theoretical quintessence of the international labor movement, which has fertilized our proletarian struggle. This means that the revolution was being prepared, before 1917, at those crossroads where the great forces of the world encounter one another. Out of this clash of forces arose the Great War, and out of this the October Revolution. And now we are told to abstract ourselves from the international situation and to construct our socialism at home for ourselves. That is a metaphysical method of thought. There is no possibility of abstraction from the world economy.

What is export? A domestic or an international affair? The goods to be exported must be produced at home, thus it is a domestic matter. But they must be exported abroad, hence it is an international transaction. And what is import? Import is international! The goods have to be purchased abroad. But they have to be brought into the country, so it is a domestic matter after all. [Laughter.] This example of import and export alone suffices to cause the collapse of Comrade Bukharin’s whole theory, which proposes an “abstraction” from the international situation. The success of socialist construction depends on the speed of economic development, and this speed is now being determined directly and more sharply than ever by the imports of raw materials and machinery. To be sure, we can “abstract ourselves” from our shortage of foreign currency, and order more cotton and machines. But we can only do that once. A second time we shall not be able to accomplish this abstraction. [Laughter.] The whole of our constructive work is determined by inter national conditions.

If I am asked whether our state is proletarian, I can only reply that the question is out of place. If you do not wish to form your judgment on two or three words picked at random from an uncorrected stenographic report, but on what I have said and written in dozens of speeches and articles-and this is the only way in which we should form a judgment on one another’s views-if we do not wish to trip one another up with an uncorrected sentence, but seek to understand one another’s real opinions, then you must admit without hesitation that I join with you in regarding our state as a proletarian state. I have already replied by several quotations to the question of whether this state is building socialism. If you ask whether there are in this country sufficient forces and means to carry out completely the establishment of socialism within thirty or fifty years, quite independent of what is going on in the world outside, then I must answer that the question is put in an entirely wrong form. We have at our disposal adequate forces for the furtherance of the work of socialization, and thereby also to aid the international revolutionary proletariat, which has no less prospect of gaining power in ten, twenty, or thirty years than we have of establishing socialism; in no way less prospect, but much greater prospect.

I ask you, comrades-and this is the axis upon which the whole question turns-what will be going on in Europe while we are working at our socialization? You reply: We shall establish socialism in our country, independent of what is going on all over the world. Good.

How much time shall we require for the establishment of socialism? Lenin was of the opinion that we shall not have established socialism in twenty years, since our agrarian country is so backward. And in thirty years we shall not have established it either. Let us take thirty to fifty years as a minimum. What will be happening in Europe during all this time? I cannot make a prognosis for our country with out including a prognosis for Europe. There may be some variations. If you say that the European proletariat will certainly have come to power within the next thirty to fifty years, then there is no longer any question in the matter. For if the European proletariat captures power in the next ten, twenty, or thirty years, then the position of socialism is secured, both in our country and internationally. But you are probably of the opinion that we must assume a future in which the European proletariat does not come to power.

Otherwise why your whole prognosis? Therefore, I ask what you suppose will be happening in Europe in this time? From the purely theoretical standpoint, three variations are possible. Europe will either vacillate around about the prewar level, as at present, the proletariat and the bourgeoisie balancing to and fro and just maintaining an equilibrium. We must however designate this “equilibrium” as unstable, for it is extremely so. This situation cannot last for twenty, thirty, or forty years. It must be decided one way or the other.

Do you believe that capitalism will find a renewed dynamic equilibrium? Do you believe that capitalism can secure a fresh period of ascendancy, a new and extended reproduction of that process which took place before the imperialist war? If you believe that this is possible (I myself do not believe that capitalism has any such prospect before it), if you permit it even theoretically for one moment, this would mean that capitalism has not yet fulfilled its historic mission in Europe and the rest of the world, and that present-day capitalism is not an imperialist and decaying capitalism, but a capitalism still on the upgrade, creating economic and cultural progress. And this would mean that we have appeared too early on the scene./ui

CHAIRMAN: Comrade Trotsky has more than exceeded the time allotted him. He has been speaking for more than one and a half hours. He asks for a further five minutes. I shall take your vote. Who is in favor? Who is against? Does anybody demand that a fresh vote be taken? yas brb[n dsys!

COMRADE TROTSKY: I ask for a fresh vote.

CHAIRMAN: Who is in favor of Comrade Trotsky’s being given five minutes more? Who is against? The majority is against.

COMRADE TROTSKY: I wished to utilize these five minutes for a brief summary of conclusions.

CHAIRMAN: I shall take the vote again. Who is in favor of Comrade Trotsky’s time being extended by five minutes? Those in favor hold up their delegate’s tickets. Who is against? The majority is in favor. It is better to extend the time than to count votes for five minutes. Comrade Trotsky will continue.

COMRADE TROTSKY: If it is assumed that during the next thirty to fifty years which we require for the establishment of socialism, European capitalism will be developing upward, then we must come to the conclusion that we shall certainly be strangled or crushed, for ascending capitalism will certainly possess, besides everything else, correspondingly improved military technology. We are, moreover, aware that a capitalism with a rapidly rising prosperity is well able to draw the masses into war, aided by the labor aristocracy which it is able to create. These gloomy prospects are, in my opinion, impossible of fulfillment; the international economic situation offers no basis. In any case we have no need to base the future of socialism in our country on this supposition.

There remains the second possibility of a declining and decaying capitalism. And this is precisely the basis upon which the European proletariat is learning, slowly but surely, the art of making revolution.

Is it possible to imagine that European capitalism will continue a process of decay for thirty to fifty years, and the proletariat will meanwhile remain incapable of accomplishing revolution? I ask why I should accept this assumption, which can only be designated as the assumption of an unfounded and most profound pessimism with respect to the European proletariat, and at the same time of an uncritical optimism with respect to the establishment of socialism by the unaided forces of our country? In what way can it be the theoretical or political duty of a Communist to accept the premise that the European proletariat will not have seized power within the next forty to fifty years? (Should it seize power, then the point of dispute vanishes.) I maintain that I see no theoretical or political reason why it is easier to believe that we shall build socialism with the cooperation of the peasantry than that the proletariat of Europe will seize power.

No. The European proletariat has the greater chances. And if this is the case, then I ask you: Why are these two elements opposed to one another, instead of being combined like the “two conditions” of Lenin? Why is the theoretical recognition of the establishment of socialism in one country demanded? What gave rise to this standpoint? Why was this question never brought forward by anyone before 1925? [A voice: “It was!”] That is not the case, it was never brought forward. Even Comrade Stalin wrote in 1924 that the efforts of an agrarian country were insufficient for the establishment of socialism. I am today still firm in my belief that the victory of socialism in our country is only possible in conjunction with the victorious revolution of the Euro pean proletariat. This does not mean that we are not work ing toward the socialist state of society, or that we should not continue this work with all possible energy. Just as the German worker is preparing to seize power, we are preparing the socialism of the future, and every success which we can record facilitates the struggle of the German proletariat, just as its struggle facilitates our socialist progress. This is the sole true international view to be taken of our work for the realization of the socialist state of society.

In conclusion I repeat the words which I spoke at the plenum of the CC: If we did not believe that our state is a proletarian state, though with bureaucratic deformations, that is, a state which should be brought into much closer contact with the working class, despite many wrong bureaucratic opinions to the contrary; if we did not believe that our development is socialist; if we did not believe that our country possesses adequate means for the furtherance of socialist economics; if we were not convinced of our complete and final victory; then, it need not be said, our place would not be in the ranks of a Communist Party.

The Opposition can and must be assessed by these two criteria: it can have either one line or the other. Those who believe that our state is not a proletarian state, and that our development is not socialist, must lead the proletariat against such a state and must found another party.

But those who believe that our state is a proletarian state, but with bureaucratic deformations formed under the pressure of the petty-bourgeois elements and the capitalist encirclement; who believe that our development is socialist, but that our economic policy does not sufficiently secure the necessary redistribution of national income; these must use party methods and party means to combat that which they hold to be wrong, mistaken, or dangerous, but must share at the same time the full responsibility for the whole policy of the party and of the workers’ state. [The chairman rings.] I am almost finished. A minute and a half more.

It is incontestable that the inner-party disputes have been characterized of late by extreme sharpness of form, and by a factional attitude. It is incontestable that this factional aggravation of the dispute on the part of the Opposition-no matter by what premises it was called forth-could be taken, and has been taken by a wide section of the party members, to mean that the differences had reached a point rendering joint work impossible, that is, that they could lead to a split. This means an obvious discrepancy between the means and the aims, that is, between those aims for which the Opposition has been anxious to fight, and the means which it has employed for one reason or another. It is for that reason we have recognized these means-the faction-as being faulty, and not for any reason arising out of momentary considerations. [A voice: “Your forces were inadequate; you have been defeated!”] We recognize this in consideration of the whole inner-party situation. The aim and object of the declaration of October 16 was to defend the views which we hold, but to do this under the observance of the confines set by our joint work and our joint responsibility for the whole policy of the party.

Comrades, what is the objective danger involved in the resolution on the Social Democratic deviation? The danger lies in the fact that it attributes to us views which would necessarily lead, not merely to a factional policy, but to a policy of two parties.

This resolution has the objective tendency of transforming both the declaration of October 16 and the communique of the CC into fragments of paper that … [A voice: “Is that a threat?”] No, comrades, that is no threat. It is my last thought to utter any threat. [A voice: “Why raise that again?”] You will hear in a moment. Only a few words more.

In our opinion the acceptance of this resolution will be detrimental, but insofar as I can judge of the attitude of the so-called Opposition, especially of the leading comrades, the acceptance of this resolution will not cause us to depart from the line of the declaration of October 16. We do not accept the views forced upon us. We have no intention of artificially enlarging the differences, or of aggravating them and of thus preparing for a relapse into the factional struggle. On the contrary, each one of us, without seeking to minimize the existing differences, will exert every effort to keep these differences within the confines of our continued work an our joint responsibility for the policy of the party.

END

nternational Press Correspondence, widely known as”Inprecorr” was published by the Executive Committee of the Communist International (ECCI) regularly in German and English, occasionally in many other languages, beginning in 1921 and lasting in English until 1938. Inprecorr’s role was to supply translated articles to the English-speaking press of the International from the Comintern’s different sections, as well as news and statements from the ECCI. Many ‘Daily Worker’ and ‘Communist’ articles originated in Inprecorr, and it also published articles by American comrades for use in other countries. It was published at least weekly, and often thrice weekly. The ECCI also published the magazine ‘Communist International’ edited by Zinoviev and Karl Radek from 1919 until 1926 monthly in German, French, Russian, and English. Unlike, Inprecorr, CI contained long-form articles by the leading figures of the International as well as proceedings, statements, and notices of the Comintern. No complete run of Communist International is available in English. Both were largely published outside of Soviet territory, with Communist International printed in London, to facilitate distribution and both were major contributors to the Communist press in the U.S. Communist International and Inprecorr are an invaluable English-language source on the history of the Communist International and its sections.

PDF of full issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/international/comintern/inprecor/1926/v06n79-nov-25-1926-inprecor.pdf