‘George Grosz – Up Out of Dada’ by Julian Gumperz from New Masses. Vol. 2 No. 6. April, 1927.

The world war marks the rise of a new period in German intellectualism. The poets — who had been so busy writing nice little verses about the lips and hips of Lulu, the queen of their dreams, singing paeans of praise to God Almighty, as disclosed in every pretty flower, and inditing passionate lines to the beauty and fertility of Mother Nature- — were suddenly interrupted in their petty business by the roaring thunder of the battlefields. Those of them who wished to evade being offered up as cannon-fodder, those of them who refused to sing the loud hymns of hatred and imperialism, if they were honest and clear-minded, were confronted by the question: What — in the face of this unforeseen cataclysm, in the face of these dying millions, in the face of a starving nation — is the value of our art, our poetics, our novels, our plays? The artist, who had been so mightily busy with his color problems, or so concerned with projecting the pale vision of his soul upon a bit of canvas, suddenly found himself with a rifle in his hand instead of the magic brushes. The l’art pour l’art business had to be closed down for a while, and a clear decision had to be made: whether to fight the war side by side with the ruling class or in some way or other to take a stand against it. Some tried to do this by escaping into the war-remote paradise of a neutral country, into the peace of pastoral Switzerland, where most of them, au dessus de la melee, soon began to chew the cud of their art problems again. Others, like George Grosz, remained in the country and fought a lone battle against Prussian militarism as best they could, each according to his own lights.

And since the artist in the prewar period, at least in Germany, was an extremely individualistic fellow, this battle was fought with individualistic methods, by isolated, and on the whole futile, gestures of revolt in the prisons, the insane asylums, the sickrooms and the recruiting offices.

George Grosz in the beginning of his artistic career was an artist very much like the rest of the breed. Raised in a small provincial town of northern Germany, surrounded by small shopkeepers, grocers and landlords, confronted in his early life with the brutality and inanities of the Prussian officers (his mother was in charge of the local officers’ clubhouse) he seems to have been vividly impressed with the ugliness, the shabbiness and the senselessness of life about him. “There is no way out!” was the dominant note of his first pictures and of the poems he wrote at the time* He himself says about this period: “I understood at the time that ethic is a lie made for fools, that men are nothing but dirty pigs. Life has no other sense than to satisfy one’s appetite for food and women. Soul — there is no such thing! The main object is to procure in some way the necessities of life. Get along, use your elbows — this is disgusting, but it is the only thing to do.” Life made him feel sick — a good stiff drink produced the only idealism and romanticism which an ugly civilization could develop.

When war was declared this “elbowing” process grew all the more disgusting, and when Grosz was forced to military service, the only thing to do was to get out of it as quickly as possible. So he punched the first officer who came along in the jaw. His action was considered shocking, outrageous, unheard of! Surely, nobody in his right mind would touch a uniform of the Kaiser! He was put in an insane asylum. In the solitude of his cell he studied the drawings on the walls, which former inmates had designed. Here, and in other places, where primitive and strong sentiments were given intimate expression, Grosz gathered together the elements of his style. The simplicity, directness and sharpness of his drawings show up his subjects in all their sordidness and brutality.

When they brought Grosz out of the insane asylum he again went for the first officer he saw and hit him in the face. Whereupon he was clapped back into a cell, which seemed to him, on the whole, more comfortable than the trenches in France. And I think something of this punch remained in Grosz and his art: his drawings continued to be constant blows in the face of officers, capitalists and all the other profiteers of a brutal society.

The war did one thing more for Grosz: it demonstrated to him that in his fight he was not alone, that there were others fighting the war machine. He began to realize that there were other men hostile to the idea of a “heroic” death for the Fatherland. He learned that outside the bourgeois world and in opposition to it was a new way of life, where there was solidarity, devotion, and a goal worth living for.

The end of the war marked that fiasco known as the German revolution. The real revolutionary forces in Germany had been underground during the war. The only exponent of the radical movement, visible to the public eye, had been the Social Democratic party which had made its peace with the ancien regime. So Grosz had to find his particular artistic way out of the dilemma into the highway of a genuine revolutionary movement. It was necessary to submerge his individual artistic revolt in the great proletarian mass movement. The instrument with which he proposed to accomplish the destruction of the old artistic ideology was Dadaism, which Grosz initiated in Berlin.

In the beginning of the year 1919 hundreds of saviors in the fields of literature, music and art were advertising as many different brands of evangelism in the streets, the concert halls, the book shops, the magazines and the newspapers of the country. “See!” they cried, “the revolution is in danger of degenerating into nothing more than a movement for higher wages and better living conditions!” They intimated that there was only one thing for the workers to do: to stop, look and listen when they, the intellectuals, revealed the significance of the red clouds in the sky. Every week witnessed a new spiritual and intellectual revelation. Till out of the ranks of these savior artists rose Dada, as opponent to all this saviorism. Dadaism was a purely artistic negation of contemporary art. Its aim was to destroy the superstition of the sanctity of art. What was the use of Rembrandt and Shakespeare, of all this gothic and classic business, of the outpourings of these pure artistic souls, if they could not produce a fighting reaction against the orgy of manslaughter which the world was witnessing?

The Dada movement in Berlin started with a show in a well-known theatre. People gathered, expecting a new revelation, a new spirit, to conquer the country. Instead: an organ began to play the most vulgar and coarse melodies; someone on the stage started reading gory details of battle from the writings of a well-known war-correspondent out of the bible. It was all so bewildering that an old maid in the audience began to cry. Whereupon Grosz, from the stage, taunted the poor woman with a most amazing harangue. By this time the audience was in an uproar, and vented its rage by throwing chairs at the stage. But the Dadaists had won their point by making everything dear to the sentimental German heart appear ridiculous.

The first public appearance of Dadaism split the artistic groups wide open. Against those who prayed that the “artistic spirit” should save the world were those who believed that the “artistic spirit” was rather unimportant at a time when Hindenburg and Noske were at their work of crushing the revolution.

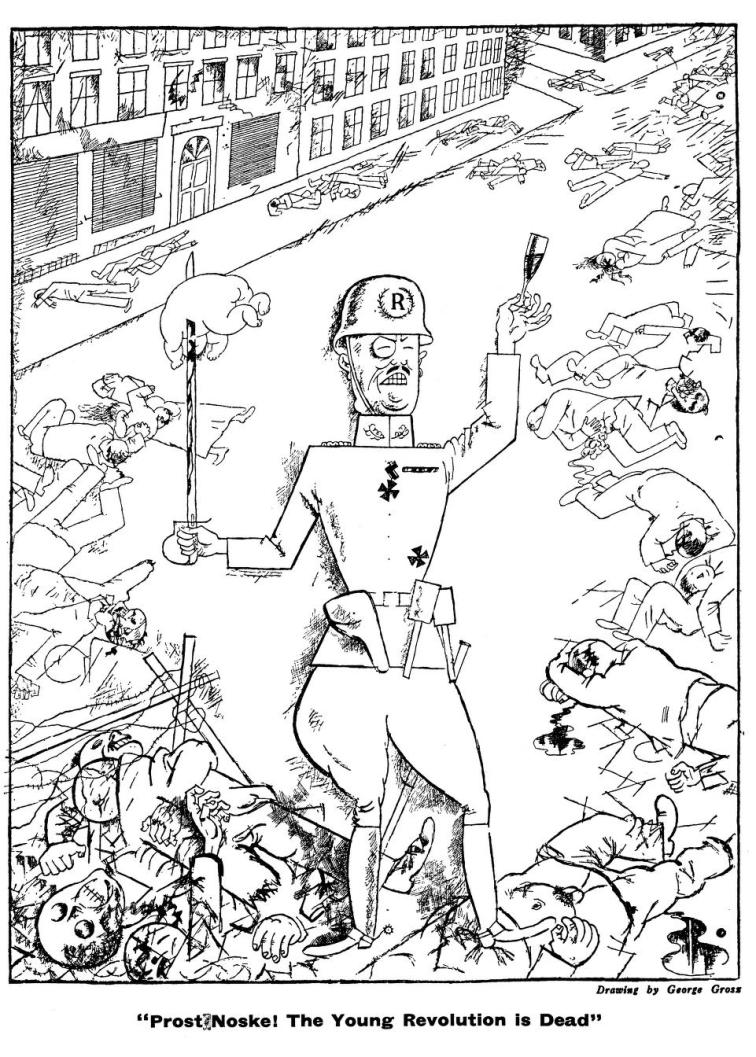

At this time Grosz began to draw his first political cartoons, which immediately had an immense success: Noske soldiers, showed up to smash his flat, judges charged him with blasphemy, with provocation of class hatred, nationalist papers pointed out that only a Jew would do such nasty work (although Grosz is a hundred per cent German), and radicals hailed him as the first great political cartoonist of Germany.

The revolution had put Grosz in touch with the radical movement and he became convinced that there could be no justification for art except as a weapon in the battle for the oppressed. Later on, a trip to Russia wiped out the last desperate remnants of his early cynicism and melancholia. Grosz has often been criticized by his comrades because he did not do anything constructive. He was asked: Why don’t you make drawings glorifying the workers? Why don’t you picture the nobility of the revolutionary spirit? But Grosz maintained that during a period of struggle the revolutionary artist has no other choice but to criticize the masters of society, and by constant, bitter ridicule to shock people out of their faith in the superiority of the ruling class.

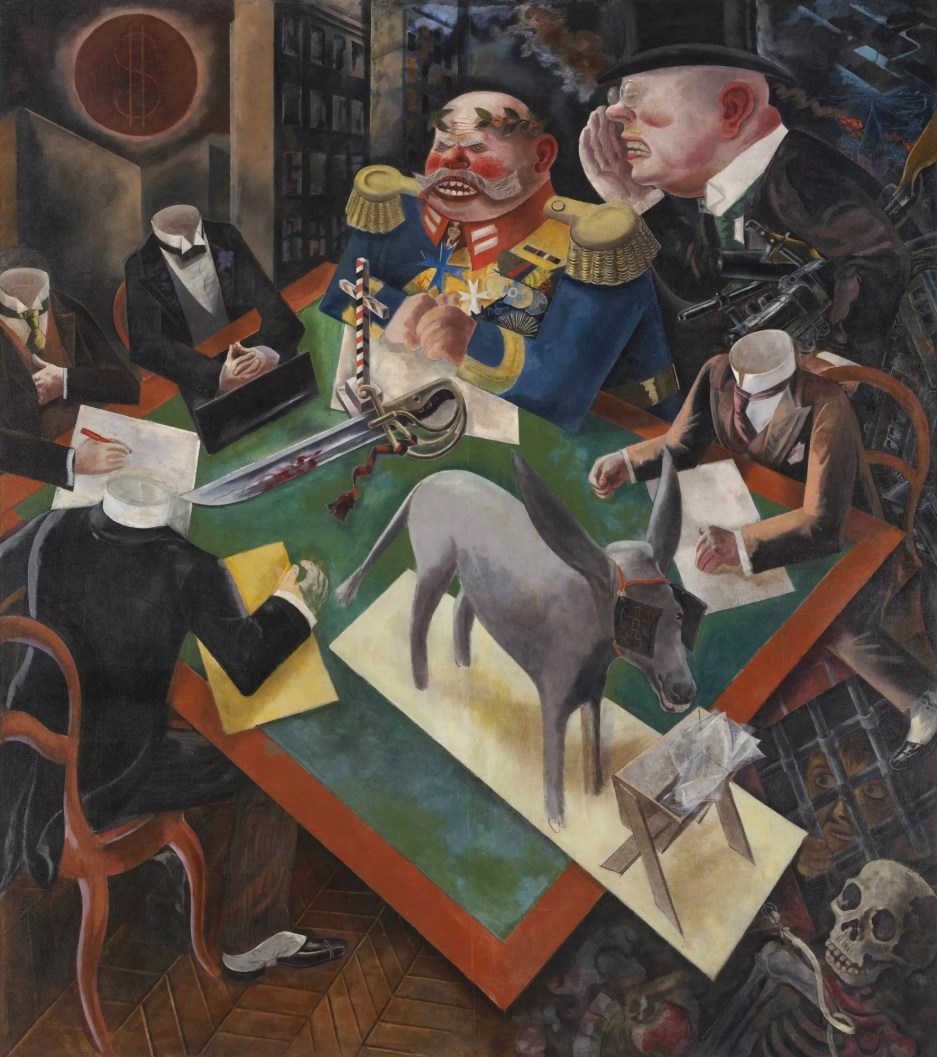

Das Gcsicht der Herrschenden Klasse was his first book of political caricatures. It was immediately suppressed “for inciting to class hatred.” As a matter of fact, the “Socialists,” who were then in power, were so bitterly lampooned for their surrender to ruling class tactics (pictures such as Ebert reclining luxuriously on the Kaiser’s throne and an officer standing on the bodies of slain workers, toasting Noske: “Die junge Revolution is tot!”) that they took action against Grosz and his book.

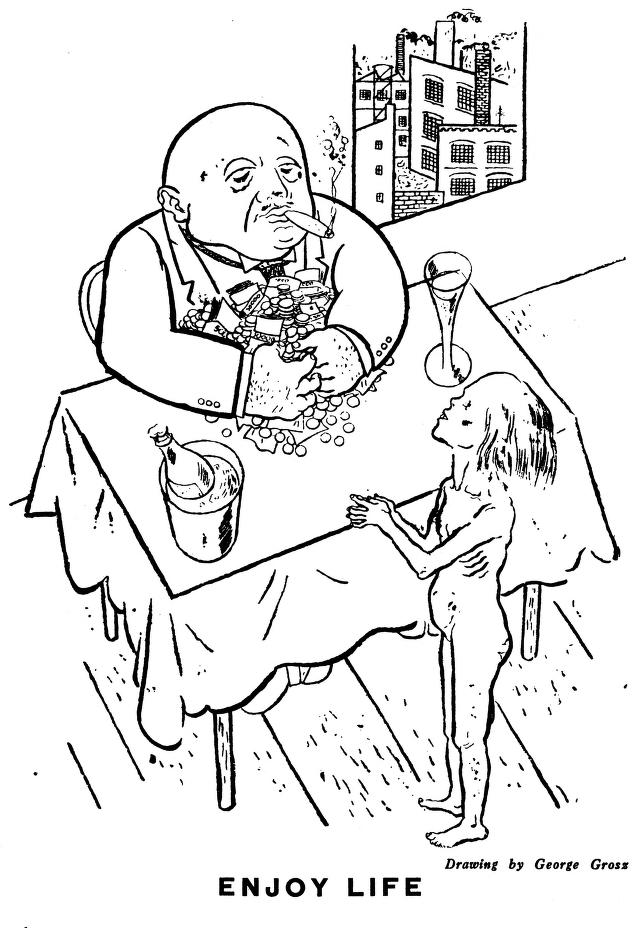

Grosz did not limit himself to political caricature, but found a new weapon in social satire.

In Ecce Homo, one of his most famous books, he showed up the everyday life of the ruling class and its satellites as a very sordid and vulgar affair. This book, which was suppressed in Germany, is a terrifically bitter and forceful criticism of the erotic life of the post-war period. It is an X-ray of the lusts and desires which are the leading motifs of a money-worshiping society. The publication of this book added another trial for indecency to his already long record. An incident that occurred at the trial may be worth narrating: in the book Grosz poked fun at a prevalent Teutonic type by representing him clad only in a helmet and a leather apron reaching as far as his hips. This picture induced the judge to ask the artist why he did not add a tiny little piece to the apron to cover the “indecent” parts of the body.

In the days before the war Grosz had planned to write a voluminous book about the ugliness of the Germans. Ecce Homo reveals his new attitude. It is an authentic portrait, not of the ugliness of the Germans, but of the deformity of German capitalist society — and probably not only of German but of capitalist society in general. This probably accounts for the fact that Georg Grosz is being looked upon, next to Hogarth, Goya and Daumier, as the world’s greatest cartoonist.

The New Masses was the continuation of Workers Monthly which began publishing in 1924 as a merger of the ‘Liberator’, the Trade Union Educational League magazine ‘Labor Herald’, and Friends of Soviet Russia’s monthly ‘Soviet Russia Pictorial’ as an explicitly Communist Party publication, but drawing in a wide range of contributors and sympathizers. In 1927 Workers Monthly ceased and The New Masses began. A major left cultural magazine of the late 1920s to early 1940s, the early editors of The New Masses included Hugo Gellert, John F. Sloan, Max Eastman, Mike Gold, and Joseph Freeman. Writers included William Carlos Williams, Theodore Dreiser, John Dos Passos, Upton Sinclair, Richard Wright, Ralph Ellison, Dorothy Parker, Dorothy Day, John Breecher, Langston Hughes, Eugene O’Neill, Rex Stout and Ernest Hemingway, Artists included Hugo Gellert, Stuart Davis, Boardman Robinson, Wanda Gag, William Gropper and Otto Soglow. Over time, the New Masses became narrower politically and more journalistic in its tone.

PDF of full issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/usa/pubs/new-masses/1927/v02n06-apr-1927-New-Masses.pdf