Marguerite Young’s looks at the extraordinary life of Rose Pastor Stokes on her death at 53 in 1933.

‘Rose Pastor Stokes’ by Marguerite Young from New Masses. Vol. 8 No. 10. June, 1933.

“I SLIPPED into the world while my mother was on her knees scrubbing the floor.”

Those are the first words in Rose Pastor Stokes’ story of her life. By the time they are published, next winter, her ashes will have been enshrined by the revolutionary workers of the United States…

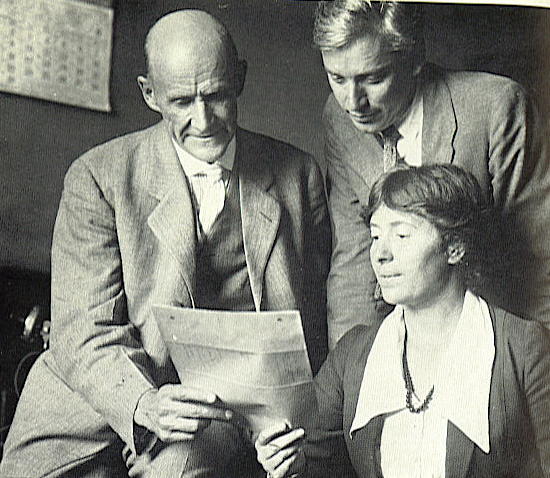

Martyrdom was upon her when I first saw her, in the autumn of 1932. But I shouldn’t have suspected, had I not already known, that the hand of the disease — the cancer which was activized by a policeman’s nightstick, falling on her during a demonstration against American imperialist intervention in Haiti — had already spread its searing fingers through her breast. She was so strong and supple and straight! Her vitality was a thousand currents flowing in every direction around her.

Her slow, packed sentences stood out like flags in my mind. What kept lifting them, afterward, was the unforgettable conviction, the spirit with which they were spoken. The memory of it stirs them even now.

It was cold in the Connecticut wood, where the tiny cabin with its one enclosed room had a stove only because Rose had delayed the interview until she could obtain one, for the reporter’s comfort. In her thin grey sweater and soft dress, she walked with a long, sure stride. Her chestnut hair was clipped and greying, but her eyes were young. It was the strength of the high, broad forehead and prominent brown eyes that held me. There were chrome flecks in the brown. They seemed at once the most deep-searching and wise, and the most naive eyes that I had ever seen. They had tried to, but could not, be trustless. I represented a press which she despised. Yet soon from the interstices she realized that I was sympathetic.

From that moment on I knew there would be no other interview exactly like this for me. My heart pounded as she said, so quietly, so certainly:

“I’ll pull through. I’m determined. I must see a Soviet America. I will see the workers here rise to power and build their own world as they are doing in Soviet Russia — a world in which there will be no unemployment, hunger, insecurity or war.”

Another day, in the cabin, she confessed for once the measure of her suffering. “I think it’s got me.” Her hand groped over her mutilated body.

Yet the same night, driving with some friends into the city to be treated, she unearthed the Red Song Book and began to sing!

The songbook dropped. Too heavy. But her voice, clear and sweet and still possessing shades of the power which once reached the highest rafters in Carnegie Hall, continued through the “Internationale.” At length she spoke, stirringly, of standing in the snow in Moscow with Clara Zetkin — standing in the snow in 1924, singing “The Workers’ Funeral March” while the breaths of the massed formed a foggy mist above — standing, singing, waiting to see the body of Lenin carried into Red Square.

I remember her, again, last winter, wracked by pain. Her voice was like an echo. She was lifting it not in complaint against the torture she had endured from neglect in a certain hospital — but in protest against the working conditions and low pay of the nurses, which she had ascertained in the midst of and despite her agony.

Her life was a mirror of the heroic struggles, defeats and glories of that sector of the revolutionary masses who entered the Communist Party after years of practical experience in trade unionism and “Socialism”; after full realization of the futility of efforts to will, organize, or charm away the irreconcilable antagonisms between the classes.

It is this — as well as the revolutionary passion with which she spent herself in years of strike-leading and anti-war activities, in which she faced jail repeatedly only to return to the struggle with greater fervor; and the mature theoretical understanding with which she performed important underground work in the party — that made her an historic American mass figure. These things and her martyrdom…

A portrait of the tyrant, Alexander II, hung in the hut where she was born in Russia, fifty-four years ago. When she was three, in the hell-hole which was London’s East End, she dreamed of ripe, ever unattainable fruits. She hungered.

Both her mother and father were workers. It was the mother who took Rose to England and set before her an example of struggle. One of the daughter’s earliest memories was how her mother went to work, one day, to discover the windows of the garment factory white-washed by a master who denied the workers’ right even to look from their bondage upon the free air outside. Folding her apron, Rose’s mother faced her fellow workers, crying, “Are we already among the dead?…Come, girls, we’ll strike!” And they struck, and won.

Frequently in childhood Rose showed the sensitiveness, the humor, the courage and headstrong determination which were to endear her later to everyone. She showed, too, an intuitive sense of social justice, a passion for which was to become the pivot of her life.

She never forgot how her mother sacrificed a new penny to replace one which Rose had given to a frozen, barefooted beggar. It was no use. Rose wept on, bitterly. Much later she was to ask, “How could I tell them it was not a new penny, but a new world, I wanted, when I myself was not aware?” and she was to record, of the plight of the submerged, the exploited, the earth’s producers:

“There are some things in the lives of the workers that cannot be told. We have no words in which to tell them, even to each other, in secret. These things, I feel, must be buried in the hearts of our class till they find expression in our deeds on the great day of our self-emancipation.”

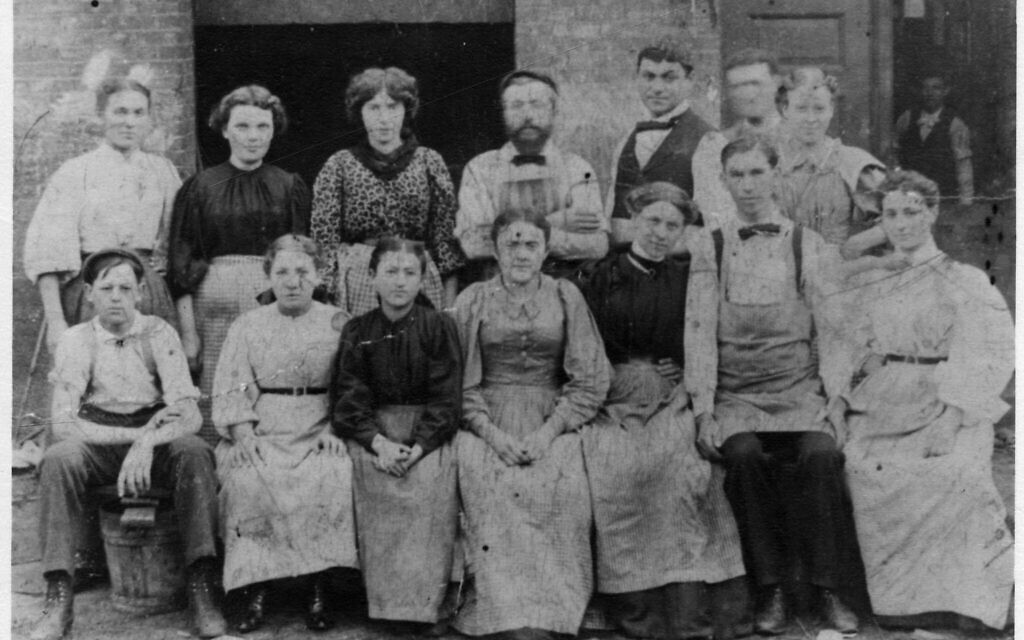

At twelve Rose became a child slave in a “buckeye,” a sweatshop cigar factory, in Cleveland, whither they had migrated* Seventy-seven cents a week. Ten or eleven hours a day. Finally a second job, until midnight, in desperation to help eke out an existence for a family who measured thin bread by the square inch.

At twenty-one she came to New York to write for a Jewish “labor” newspaper! (How she writhed under the desk’s orders for half-truths!) Although for years she had known only two books, Les Miserables and Lamb’s Tales, she had an undefined resentment even then against the fact that all the poor in Shakespeare were buffoons.

Now began to dawn a consciousness of the economic-socialpolitical nature of the misery of the workers. Rose saw beyond her mother’s trade-unionism. She joined the Socialist Party.

It was 1906. Rose had just married J.G.P. Stokes. Even then Rose perceived the contradiction in an “independent” millionaire-philanthropist politician backed by William Randolph Hearst — so instead of a Hearst gubernatorial nominee, Stokes became a “Socialist.” I think that, to Rose, the union symbolized her belief that the lion and the lamb could lie down together without disaster to the lamb.

With Upton Sinclair and Jack London they went campaigning through the Mohawk and Hudson Valleys, and into the South. The Intercollegiate Socialist Society, they called themselves. From then on it was continuous battle. With striking hotel workers (she considered this one of the most important) with telegraph operators, restaurant waiters, musical instrument workers…against profiteering butchers in Philadelphia…against the division of southern, white and Negro workers by race discriminations….

Her eyes were open to the realities of the “Negro problem.” Writing later of an incident of that period, she said:

“Dr. W. E. B. DuBois was also a guest. I found him a cold intellectual with frozen sympathies. He was perhaps the first black man to make me realize that not all men whose skins are black are oppressed proletarians; that the black like the white workers have in their midst the shrewd reformers concerned not with freeing the workers, but with keeping them in need of ^social service’ which, like the Company Store, weaves about its victims an eternal web of debt and servitude.”

And then early in 1917 Rose resigned and went into the American Party, a pro-war, reactionary group. But in less than a year she returned to her own. The cosmic October days exploded her illusions. Seeking defenders of an anti-war resolution which a militant minority had forced upon the majority of the Socialist Party, Rose was drawn into the left wing and immediately began her famous speaking tour with Eugene V. Debs. Already convicted under the wartime sedition laws (Woodrow Wilson pardoned her) she was indicted again for helping to form the Communist Party in 1919 — and once more in 1922, with 86 others, for participating in the Communist convention in Michigan.

Stokes never returned to the Socialists. When the two were divorced in 1925, the newspapers again gushed over the sudden end of a stale and puerile Cinderella-romance theme which the yellow journals had created. In reality they had been divided for years by political differences.

From Rose’s home Party work was going forward. She renewed her interest in drawing. She never became, as the newspapers reported, a “quiet-living artist.” She almost apologized, in fact, for exercising her talent. She seemed to consider it a self-indulgence.

For the most of the liberal and socialist associates of other years Rose had little more than contempt, toward the end. She was acutely aware that most of them turned reactionary in the crisis which sent her forward. “My life with them.” she said once, “was in another world. They still live in that world.”

Referring to an incident in her childhood, Rose wrote in her autobiography one sentence that fits, and reveals her entire life:

“I had no fear — had never been taught to fear, never been threatened with bogies, or ghosts, or devils.”

Her inextinguishable militancy is reflected in a recent letter to her husband V. J. Jerome written from her hospital bed at Frankfurt.

“Hitler speaks around the corner tonight. The hall is in a rich respectable neighborhood. If I were not so ill, they’d probably throw me out of the country. I agitate everybody.”

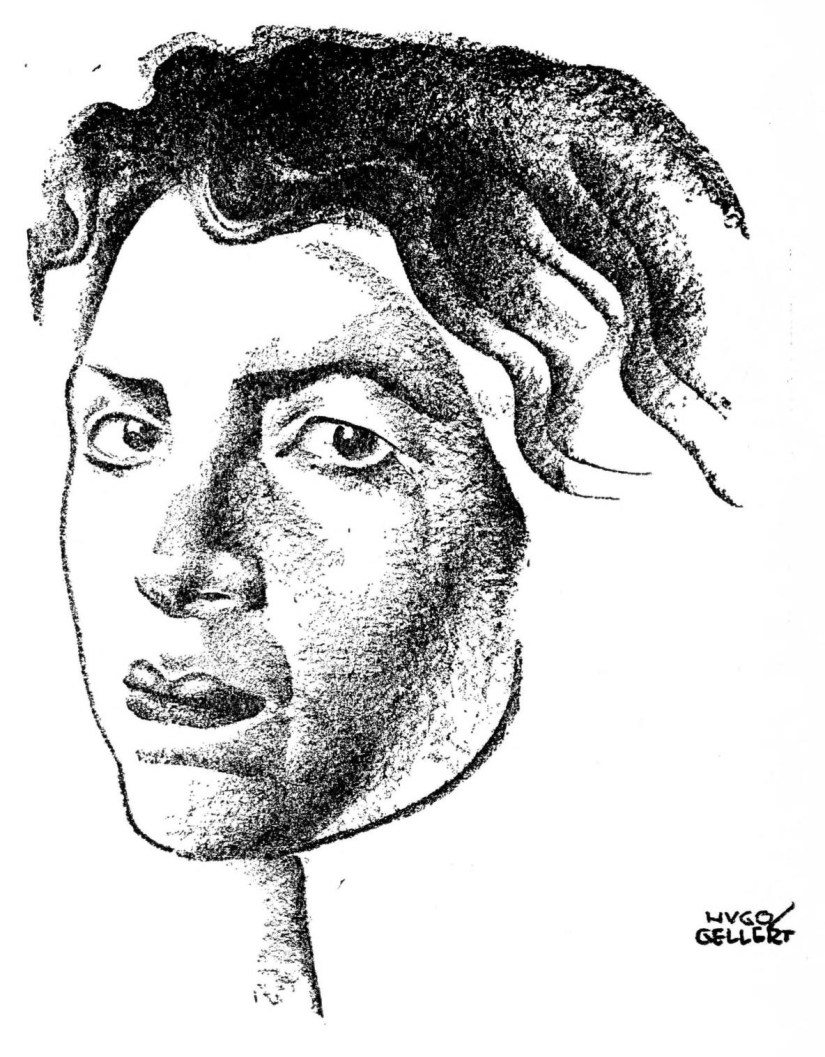

The New Masses was the continuation of Workers Monthly which began publishing in 1924 as a merger of the ‘Liberator’, the Trade Union Educational League magazine ‘Labor Herald’, and Friends of Soviet Russia’s monthly ‘Soviet Russia Pictorial’ as an explicitly Communist Party publication, but drawing in a wide range of contributors and sympathizers. In 1927 Workers Monthly ceased and The New Masses began. A major left cultural magazine of the late 1920s to early 1940s, the early editors of The New Masses included Hugo Gellert, John F. Sloan, Max Eastman, Mike Gold, and Joseph Freeman. Writers included William Carlos Williams, Theodore Dreiser, John Dos Passos, Upton Sinclair, Richard Wright, Ralph Ellison, Dorothy Parker, Dorothy Day, John Breecher, Langston Hughes, Eugene O’Neill, Rex Stout and Ernest Hemingway, Artists included Hugo Gellert, Stuart Davis, Boardman Robinson, Wanda Gag, William Gropper and Otto Soglow. Over time, the New Masses became narrower politically and more journalistic in its tone.

PDF of full issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/usa/pubs/new-masses/1933/v08n10-jun-1933-New-Masses.pdf