An excellent three-part expose by Robert L Curden of the conditions in Henry Ford’s hellish auto plants from A.J. Muste’s Labor Age.

‘The Worker Looks at Ford: Speed Is Henry’s God’ by Robert L. Curden from Labor Age. Vol. 17 Nos. 6-8. June-August, 1928.

I. The Rumor System

Detroit is a city of rumors. No murmur from the beehive of the auto industry ever reaches the newspaper offices; not a breath of the fetid factory air penetrates the editorial sanctums. Not that the manufacturers don’t get space—whole sections of the Sunday editions give them free advertising and give the worker a nice contented feeling that he’s got a lot for his dime!—nor do I mean that new factories and factories opening up after a shut-down don’t get space—Ford made the headlines last fall when he opened up—but we had never been told that there had been a shut-down, in the first place. Unemployment is never mentioned in polite newspaper circles; and as far as the papers go the public is ignorant of the many industrial accidents which happen in this city. But such news comes through. A very efficient word-of-mouth telegraphy system has been built up, so that if a plant at one end of the city lays off men every worker in town knows of it in a very few hours. It is the only way in which the worker is able to get the news of industry which really interests him.

The investigator then, since he cannot get at the facts through official sources, must rely on this “rumor” system; or he can dig in for himself and speak with the workers at the plant in which he is interested. The weakness of the former method is self-evident: it is unreliable as far as the actual detailed facts of a situation go, just as all word-of-mouth communications are; only general impressions are given. The latter is reliable and efficient: you get at the kernel of a situation in less time and with more surety of the facts through personal contact. That is especially so if the workers are unaware that “they are talking for publication.” Even here you must guard against rash generalizations. The most that can be said is that certain situations appeared in certain lights to certain individuals. I have followed this plan. From the observations of Ford employes over a period of four years up until the present I have selected what seem to be typical causes for complaint. They may not exist over all the factories, to be sure, but they are in large enough situations to warrant attention and criticism. With that in mind, let us get “down to brass tacks.”

Personally, Henry Ford would seem to be a sincere hard-working man who has “risen from one suspender.” He has never forgotten it. The long hours and the hard toil which it took to get his “‘flivver” idea on its feet have never been erased from his mind; and he thinks that everyone else should do the same—for Henry Ford, of course. He believes that he is giving his workers a “fair” day’s pay and he expects from them a “fair” day’s work. “High wages cannot be paid unless the workmen earn them. The high wage begins down in the shop. If it is not created there it cannot get into pay envelopes,” he says. He has the typical “self-made” frontier psychology—“If I did it, you can.” He throws out the “You” part of it like the finger of Uncle Sam used to be on the war posters with “Your country needs You.” He believes that “brains will come to the top,” just like froth on beer. The really intelligent mechanic will not remain content with being a machine-hand. He will think of ways of cutting out waste; he will look around him and find out where men and machines can be more efficient (a nice way of saying speed-up); he will do all that he can to help the company in the particular part of the plant where he happens to be laboring. He will eat Ford, drink Ford, sleep Ford, work Ford, and—when he is able to do so—play Ford! For Henry still has a naive idea that intelligent workers get a creative joy out of tightening up nut 99 on 999 cars for eight hours a day. As an aid for such honest, red-blooded Americans Ford maintains classes where they are taught everything from safety slogans to handling “wop” labor in Italy. Does he not say himself, “The Americans in our employ do want to go ahead. The foreigners, generally speaking, are content to stay as straw-bosses”? And with all good Board of Commerce members Ford says that there is plenty of room at the top of the ladder, “The vast majority of men want to stay put. They want to be led. They want to have everything done for them and to have no responsibility. Therefore, in spite of the great mass of men, the difficulty is not to discover men to advance, but men who are willing to be advanced.” All of which, you must admit, is as much good for our generation as his fiddling contests and his old-fashioned dancing!

II. Production

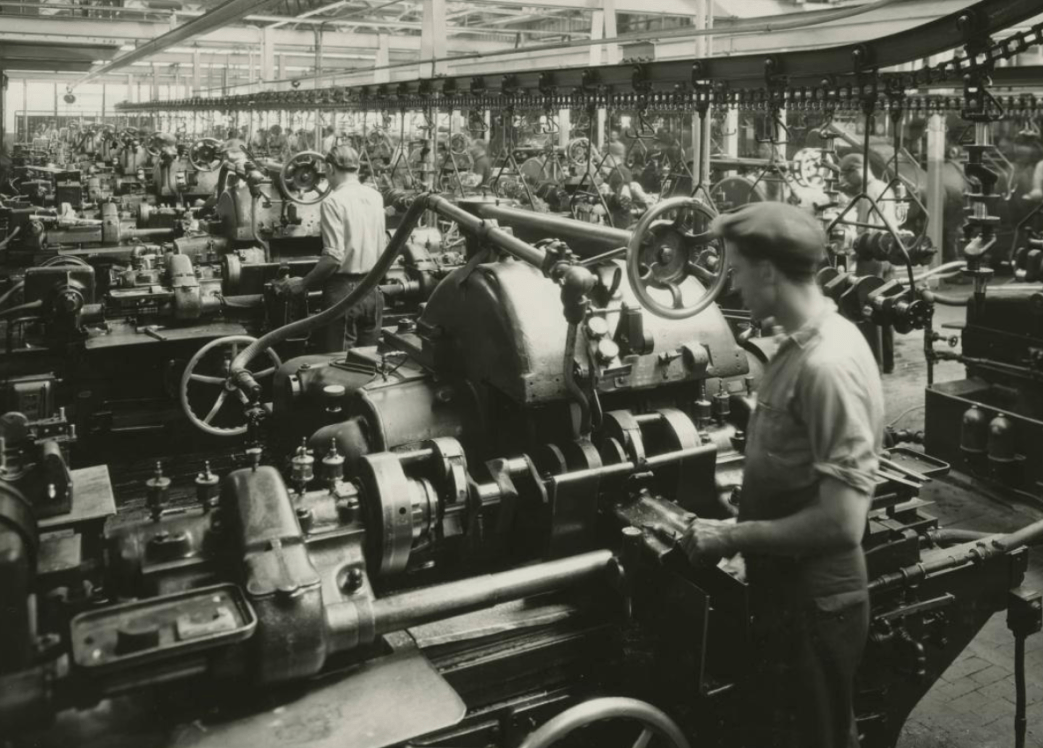

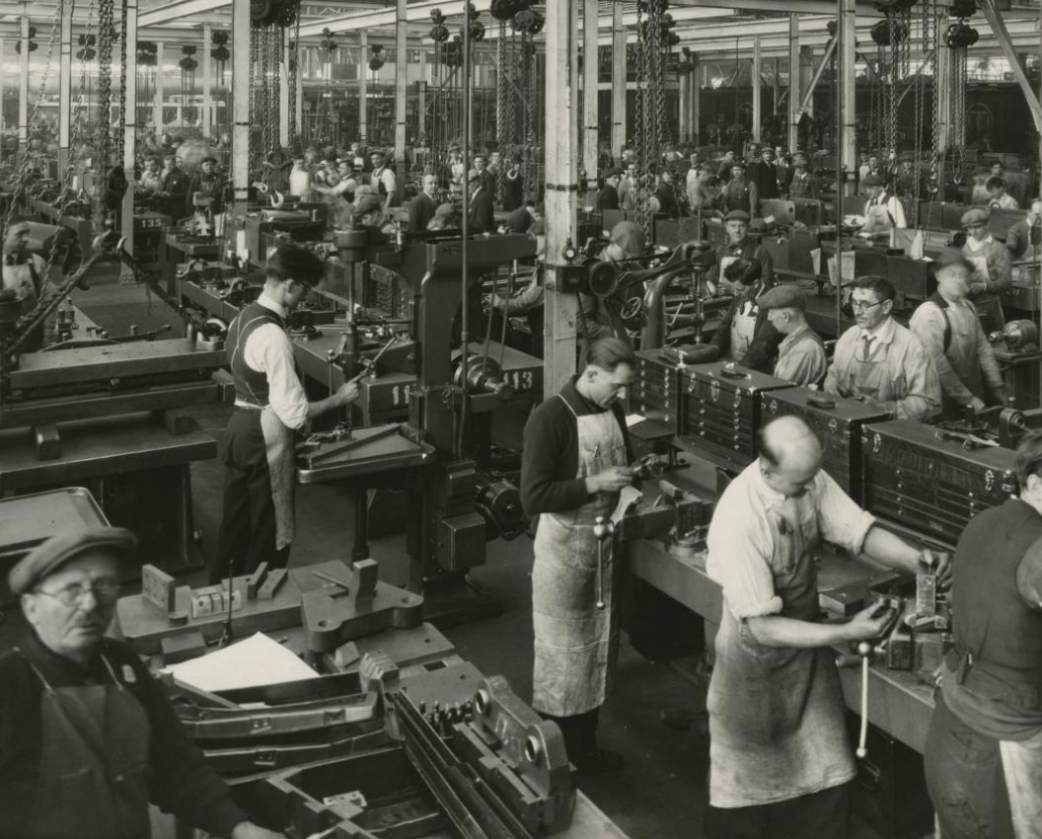

Speaking of working conditions in the Ford plants, a former employee had this to say to me, “You’ve got to work like hell in Ford’s. From the time you become a number in the morning until the bell rings for quitting time you have to keep at it. You can’t let up. You’ve got to get out production (a word, by the way, which no Ford worker ever slurs over or mispronounces), and if you can’t get it out, you get out.” Ford, with characteristic complacency, chimes in, “It is pretty well understood that a man in the Ford plant works…Any one who does not like to work in our way may always leave.” Speed is the one god before whom there are no others in the Ford plants.

The amount of work to be got out each day comes from the office. It is divided among the various departments. The department heads divide up the work of their respective departments, and assign to the foremen their sections. The foremen in turn go to the straw-bosses and give them their orders, and the strawboss is then responsible for the work the men have to get out. Thus, the only man of the hierarchy with whom the worker comes in contact is the straw-boss; he gets all the abuse when there is a speed-up or a lay-off. It is really surprising—the way in which the workers boil over about their straw-bosses! But production, as ordered from the office, has to be got out, though the heavens fall. Speed-up is inevitable.

In many departments the workers are not allowed to speak to one another. One worker told me of how a superintendent had seen him speaking to his mate during a slack time—a rare, rare occurrence in Ford’s— and the superintendent had come over and told him that a factory is no place for talking. He made it very clear to the worker that workers can work eight hours and work, or get out. It seems to be a general rule over both the Highland Park and River Rouge—pardon me River Rouge is now Fordson—plants that workers cannot wash themselves until the bell actually rings for quitting time. During the time he is working, if a worker wishes to go to the toilet, he must be relieved. Even at lunch-time, in several departments, the worker must be relieved before he can eat. Regarding lunch periods there seem to be two systems: one whereby the worker puts in eight hours and twenty minutes, gets twenty minutes for lunch and is paid for eight hours; the other, whereby the worker puts in eight hours, gets half-an-hour for lunch and is paid for eight hours. This latter plan seems to be in effect only in those places where there is no rush. I have found only a few cases where it happens in the Fordson plant. You can see that with twenty minutes for lunch, the workers simply have to gulp down their food—just like a cow does, swallow and try to chew afterwards. The workers don’t even get time to clean their hands; nor can they get out the bad factory air, which persists in spite of Ford’s really good sanitation and ventilation systems. At all costs, the machines must be kept running.

Machine Is Boss

The company is not content with prohibitions of what may seem injurious to high speed production. Speaking of this to a Fordson plant worker recently, I got this reply, “Am I bossed around? No, I don’t need to be. The machine I’m on goes at such a terrific speed that I can’t help stepping on it in order to keep up with the machine. It’s my boss.” Another speed-up scheme which they have reminds me of a part in “The Jungle”: “Jurgis saw how they managed it; there were portions of work which determined the pace of the rest; and for these they had picked men whom they paid high wages and whom they changed frequently. You might easily pick out these pace makers, for they worked under the eye of the bosses, and they worked like men possessed. This was called ‘speeding up the gang’ and if any man could not keep up with the pace there were hundreds outside begging to try.” Although differing in a few minor details, the Ford scheme is essentially similar. Expert machinists come and work on a machine for a day. At the end, as is to be expected, their output far exceeds that of the ordinary worker, who is then told that his output must come up to that figure within a certain length of time. The fact of this man’s speeding up speeds up everything else: the man before him must “step on it” in order to keep him supplied with materials, and the man after him must increase his pace so that the materials don’t pile up on him. If the worker cannot make the pace he is recommended for transfer” by his foreman. Theoretically this means that the man is transferred to some department more suitable for his personality; actually it means that the worker is put into a department where he ordinarily cannot last a week, It’s “elimination of the unfit” in a nice way. One worker tells me that in times of great unemployment the company doesn’t even hang on to that formality. The department head simply fires the fellow who isn’t speeding-up; there are plenty outside who are “begging to try”.

How much credence can be given to this allegation is doubtful, for there are always thousands of men seeking employment at the Ford plants. The company wouldn’t have to wait for slack times in order to do away with the formality. Another scheme is to have a production schedule attached to each machine. From time to time this schedule is increased— ostensibly after timing by one of those “scientific personnel” men—and the worker must keep up with the schedule. No obstacles in the way of high pressure production can be tolerated.

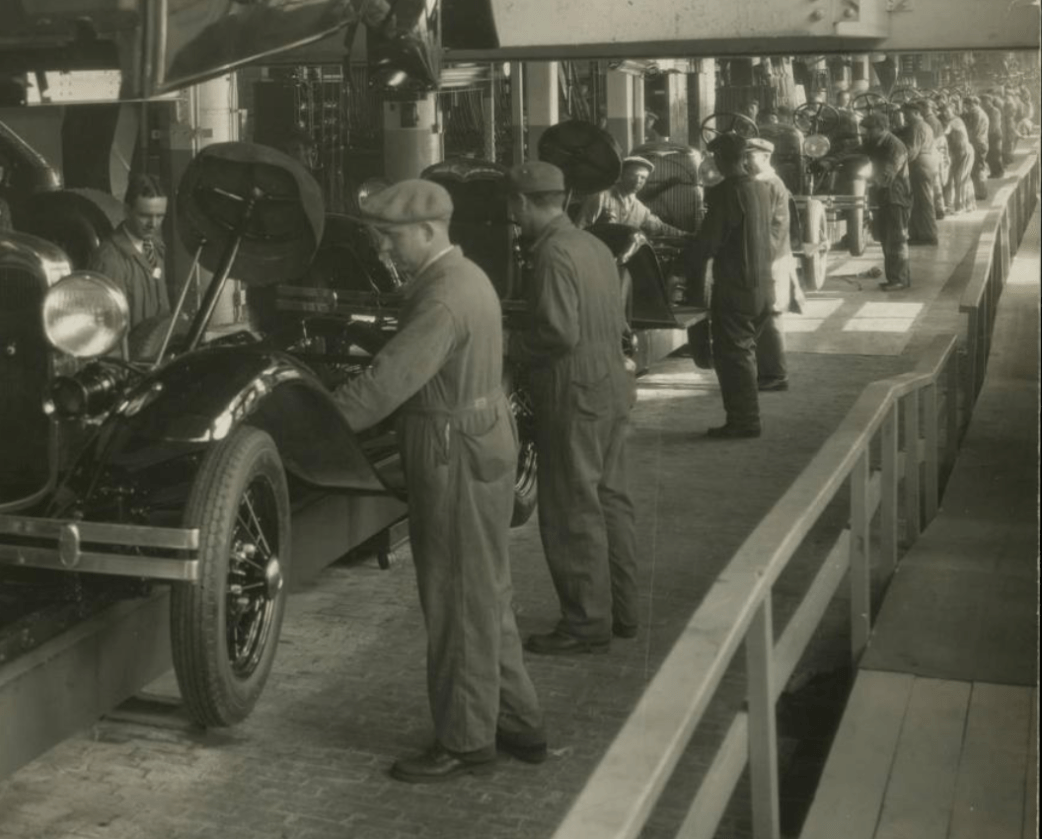

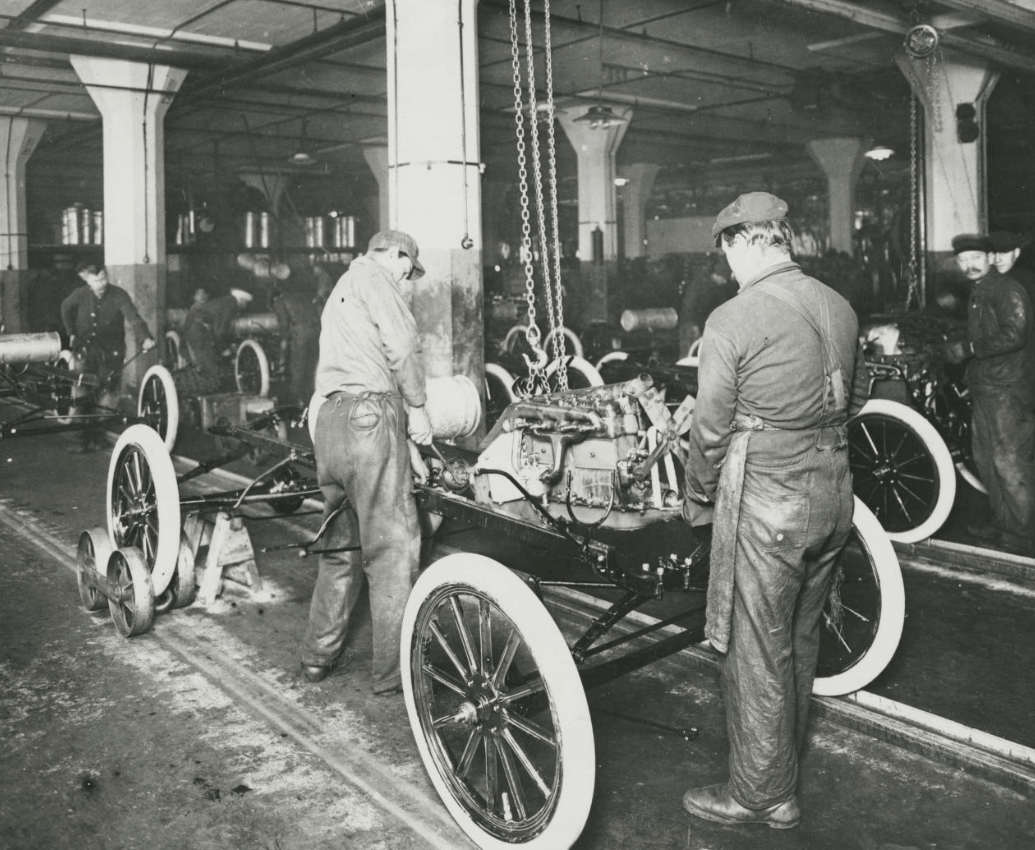

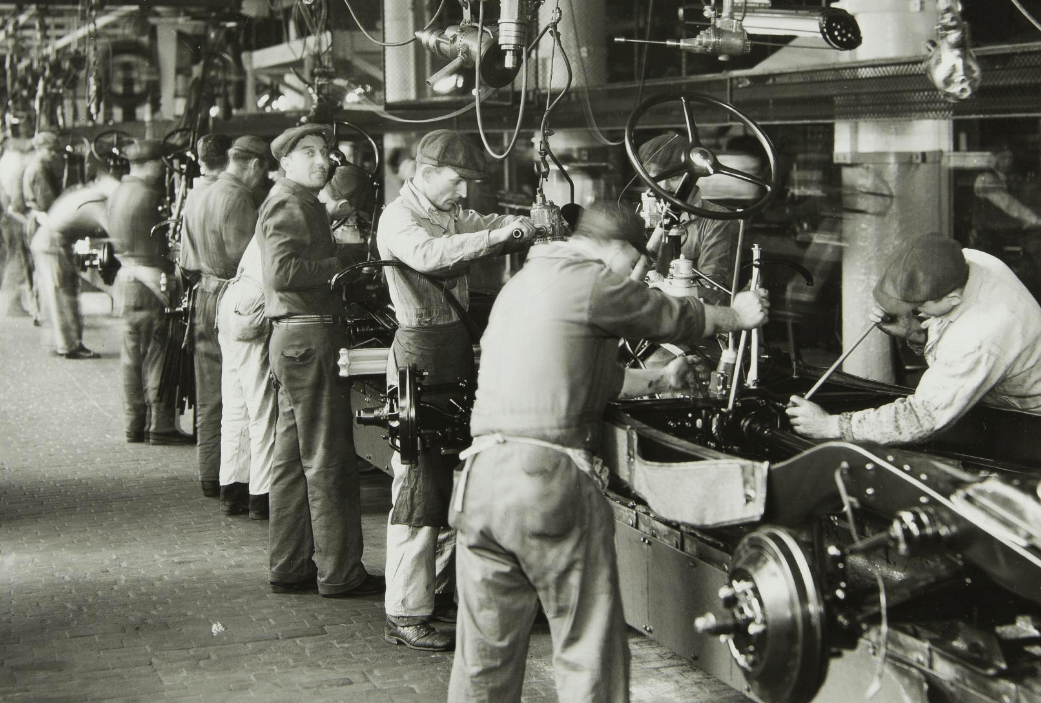

That Sweaty Line

It is on the line, however, that the real speed comes out. This is how a perfectly safe and sane conservative tells of it in the Michigan Manufacturing and Financial Record: “Each man has his specific space and his special operation to perform. It may be merely the tightening of a nut, but it must be done quickly and well, and within a set time, for further construction depends upon his work being completed and upon his being out of the way.” The men work like fiends, sweat running down their faces, their jaws set and eyes on fire. Nothing in the world exists to them except that line of chasses bearing down on them relentlessly, like a steamroller determined to crush them. The chasses come through on a conveyor which moves at a relatively fast rate. As each chassis passes the worker has to do his particular job before the next one comes. The line moves fast and the chasses are close together: the men go like lightning; some underneath on their backs on little wagons, propelling themselves by their heels all day long, fixing something underneath the chasses as they move along: others work frantically, with bent backs and faces tense, tightening up and putting on screws and bolts; they all work quietly and swiftly, like silent slaves with an unseen taskmaster over them. Their sweat is the sign of their labor; the impression of the whole factory is sweat; the whole district reeks with sweat. For sweat is a sign of speed, and speed is Henry Ford’s god.

III. Ford’s Flim-flammery: Seeing Through Henry’s Game

ALL this speed-up of which I wrote last month A tends to make the worker cease to think of himself as an individual; he, in his own mind, becomes just one number among 163,000 other numbers; in the din and roar of the presses his personality unconsciously fuses with them; his brains merge ‘into the whirling wheels of the lathes; man and the machine are indistinguishable. They are one.

Mass production is possible only through minute subdivision of labor. In a capitalistic society that means drudgery and monotonous toil for the worker. In the Ford factories, paragon of capitalistic excellence, this has been so well worked out that the factory guides point it out with pride to the curious visitors. They point at a job where all that the man has to do is to take a piece of steel, put it in the machine, and then pull a lever. They show visitors men who do nothing all day long but look at the threads on screws. Even on the sweated line, they will gleefully tell you of how the workers have only to do one little operation all day long, for all the weeks and years that he will be with the company. “And,” they say, “because the men don’t have to think about their jobs, they can think for themselves about anything they may desire.” Which is all right if the workers had ever been given a chance to think. Most of the workers have had little or no schooling; and those who have been fortunate enough to snatch a little learning have been unfortunate enough to settle down to read or to think. During the day he saw and heard nothing but machines; at night he wanted have been educated under the same principle upon which the Ford factory is run: viz., absolute obedience and docility. They have never been taught to think; and they do not care to think. Thinking is hard work, and the worker gets enough hard work in the factory without wanting it voluntarily. All of which means that they get to like their monotonous jobs. Of course, the public never hear of those things when they read, “Several years ago an executive order that every man was to change his job every three months was put into effect. To the surprise of everybody this order was fiercely resisted by the majority of men on the so-called monotonous jobs.” If we are to accept that statement at its face value—which is an extremely dangerous assumption with Ford publications—there are many explanations. In the first place, what man, thinker or not, when placed in this environment could continue to keep his mind straight? All men sooner or later fall into habits, and it is not to be expected that men who have never had a chance to think things out should demand changes in jobs, which would require quite a little mental effort. Even with those whose minds are ordinarily acute and keen, the machine routine takes its toll. One student in the Industrial Research Group in Detroit last summer, who was on a similar job in another factory, told me that after a time he simply could not escape. Mind must bow to the machine!

Another reason why the men did not want to change jobs is rather naively stated by a superintendent, quoted by W. L. Chenery in the N. Y. Times, August 10, 1924: “We tried the experiment once of changing men from one machine to another. Most of them don’t like it. Lots of fellows get to thinking that the machine belongs to them. Others hate to learn new things. It is fortunate, because the jobs with variety in them are fewer than the monotonous ones.” (Italics ours.) In other words, the workers were told that if they were not satisfied with what they had, there were plenty outside just begging to be satisfied.

That such a change would be welcome to quite a large number of the workers I have no doubt. The workers with whom I have spoken have been about equally divided on it—the older men not wanting change, the younger desiring it. Even with those opposed to it the proposition can be made attractive if you give them a say in how it’s going to be worked out. You have noticed that it was by “executive order” that the Ford plan was initiated; evidently the workers were not important enough to be taken into consideration.

Feet of Clay

The argument that the worker becomes attached to his machine was given a cruel crack on the head by Ford’s own actions in the summer of 1926. If the workers had ever cherished any such illusions they were speedily divested of them when Ford gave them all the gate. Really, up until that summer, the workers of Detroit had set up Henry as a little tin god, to whom the poor, forlorn workers could always run in times of stress and unemployment, and always get a job at five dollars a day. Dodge might close; Hudson might shut-down; even General Motors might lay off—but Henry Ford, never! It was something which was simply outside the compass of the worker’s mind. It was a disaster as unthinkable as the end of the world. For had not Ford himself said that he was interested in the lives of his workers? That only when workers were well housed, well fed, and otherwise well taken care of, would they be efficient? Was it not written that he believed in paying five dollars a day because they could not be efficient on less than that; that his speed was only so fast because slackness would break down the worker’s character? The workers of Detroit did not believe that Ford was closing down until their wages began toppling because there were so many Ford ex-workers clamoring for work outside the gates. One company manufacturing automobile bodies was able to pay 35 cents an hour for a job for which formerly they had paid 60 cents, so great was the rush for jobs. Then all the Ford myths were exploded. The sufficiency of the wages fable was blown to pieces when the city Welfare Department, in explaining a $300,000 deficit in its budget, declared that it had taken nearly all this extra money to take care of the Ford unemployed. At the same time the Detroit Community Fund quota was raised, as were those of all other charity organizations. The grim figure of poverty stalked the Detroit streets that Christmas! Ford swept everyone out—“gold star” men, minor executives, long time workers. All went out when the Fords decided to have a new model. The worker realized rather bitterly that he is but a bubble on the industrial sea.

A Grandiose Gesture

In spite of that, many of the old time employees believed that when the plants reopened they would be given jobs. It was not a matter of thought so much as it was an article of faith. Accordingly, they failed to get the point of Ford’s grandiloquent splurge to the newspapers that he was going to help solve the crime situation by removing idleness from the young men of the city. Idleness, said Ford, in effect, produces crime. Most criminals are young men. So, in order to save society, “I will see to it that 25,000 potential criminals are removed from the streets. I will give them jobs in my factories, thus effectually keeping them from crime.” The press, of course, went into hysterics of praise; and made the worker feel that in Henry Ford society had at last found its messiah and savior. The plants opened. The young men, new and former employees, were taken on. The old men, the men whose hair had whitened in the service of Ford, were refused employment; even men who had been with the company for over ten years were told that there was no room for them. These old men were made to understand that they are nothing but old rusty tin cans on the garbage heap of society.

These workers, and other workers, unfortunately, did not read what Henry said to Paul Kellogg for publication in the February issue of the “Survey Graphic.” This hypocrite-extraordinary blandly admitted that when men got into the rut of habit he had no further use for them. The old men, having become used to certain operations and certain speeds, could not adjust themselves to the new situation. New blood was needed.

Before I go on to speak about the results of such policies, let me refer to the five day week myth. Many people understand that the Ford workers get the same pay for five days’ work as they formerly did for six. This is not so. If the worker puts out as much production in five days as he used to put out in six, he gets six days’ pay but, as Ford himself says, “Not all employees are earning up to the full scale of wages. They never will.” (Detroit News, February 12, 1928.) I would say that very few are making the increased rate of pay, but in spite of that, this incentive has been instrumental in spurring the workers to greater speed. For December 26, 1926: “It (the five day week) is satisfactory to us. We are getting a higher average efficiency than on the six-day basis.” The five day week, introduced at a time when Ford did not have enough work for six days, is little more than an attempt to make respectable a simultaneous wage cut and speed up.

I am reminded that as yet I have said nothing about the wage scale at Ford’s. It is stated that the minimum daily wage in the plants is five dollars for the first 2 months and six dollars after that, and that 60 per cent of the workers earn above that amount.

The High Wage Lie

This may appear to be a “satisfactory wage” to those who are not acquainted with the cost of living in Detroit and the unemployment that has existed there in recent years. The situation was summed up accurately by the Rev. Reinhold Niebohr, a Detroit clergyman, writing even before the great Ford lay-off in 1927:

“Outside of a few thousand highly skilled workers such as toolmakers, die-makers and pattern-makers, it is hardly possible to find a Ford worker who earned more than $1500 during the past year…. Years ago when — the five dollar a day minimum was established, which meant 30 dollars a week, the Ford boast that an adequate wage obviated the necessity for charity was not an idle one. Today it is an idle boast, for living prices have well-nigh doubled and the weekly wage still hovers about thirty dollars…the actual wage is immeasurably lower than in 1913…The statistics of practically every charity reveal not only a proportionate but frequently a disproportionate number of Ford workers who are the recipients of charity.”

This situation was greatly intensified during the year 1927 when tens of thousands of workers were laid off without any unemployment insurance or company help of any kind to see them through the terrible emergency.

Employees say that it is the Ford policy to eliminate salaried workers whenever possible and “substitute men who work by the hour,” says the New York Times of December 26, 1926. “These, in turn, are working under the spur of the five day week and higher pay.” Drive the men until they drop; you can always get plenty of fresh ones!

IV. Fruits of Ford’s Speed-Up: Monotonous Toil Breeds Machine-Like Men

It would be unwise to conclude these articles without a word as to the gifts of the great god Ford to his loyal and contented workingmen. Some few years ago Ford hit on an idea—or one of his hired men did—of making the public think that he is a good kind-hearted old gentleman and the workers think that they are getting a hand in the spoils. This was the much trumpeted “investment plan”. By this plan the workers are allowed to invest up to one-third of their bi-weekly pay in Ford “investment certificates” until their total investment is equivalent to one year’s wages. The company in one of its booklets says, “Employees are permitted to deposit a portion of their earnings under the Ford Investment Plan, under which they are guaranteed a return at the rate of six per cent per annum on all multiples of fifty dollars deposited; and the Board of Directors may, at their discretion, return a higher rate. The returns so made have never been less than 12 per cent per year.” Sufficient comment on this is the remark passed by a colored worker in my hearing, “They don’t need a limit on the deposits. Who could save up two thousand bucks out of twenty-five and thirty bucks a week?”

Ford’s Welfare Department

Ford, not believing in charity, employs all sorts of men commonly called disabled, such as legless, one-armed, blind, deaf and so on. He gives them all the work they can do, and “each is happy and self-respecting, holds down a good job and does his work well.” Henry, out of the bounty of his heart, does not want any man to lose his self-respect—except when it stands in the way of profits. There are also the Ford stores, which sell foodstuffs very cheaply and make profits. They used to be open to the public, but the retail stores, egged on by the chain concerns, set up such a howl that finally Ford closed the stores; only employees can get their groceries, shoes, and medicines there now. Then there is also the Henry Ford Hospital, whose rates are so high that no average Ford worker can ever see the inside of it—even with the special rates for such workers. The welfare department also maintains a real expert and grants emergency loans. This department was unknown to the Ford workers with whom I talked. But such features look nice in Ford propaganda. And of course, there is the inevitable band and the singing society, whose members do no hard work and provide the company with good advertising. Welfare is just as much a pious fraud in Ford’s as it is everywhere else.

There are several other schemes which aim to keep the workers contented, but space forbids my going into them here. These instances I have spoken about are but indications of the hypocrisy behind the Ford organization.

Now as to the results. In the plant itself, the men have become dull, machine-like creatures. They become used to their monotonous toil and they want no change. This applies especially to the older group of workers, those between 30-40 years old. The younger men resent the speed-up intensely. They take it out on their mates, for if anything just goes wrong for a moment the anger that blazes forth appalls you. And outside the factories, if you happen to touch a sore spot the worker can say nothing else than “them goddamed bosses,” and other less printable expressions: he just blows off. This resentment, if directed into right channels, would be invaluable, but as it is now, it spends itself in useless personal quarrels. This lack of social resentment—I mean resentment of the whole production system—is also due in large part to the fact that most of the young workers in Ford’s think that they are going to be there only temporarily; they know that Ford works you to death and the only reason they are in it is because they can’t get jobs any place else. It seems unthinkable to them that they could be condemned to a Fordized life. Naturally, it is hard to interest them in organizing.

So much for individual results; let us glance at the social implications of the low-wage-speed-up “American plan.” A couple of years ago the Rockefeller Foundation uncovered such a pest-hole of prostitution in this city that the newspapers and the police had to make the public believe they were doing something about it. The city is still rotten with prostitution. There are two contributing factors: the ten-cent stores and department stores supply the women, because of the notoriously low wages paid to women workers; factories, like Ford’s, supply the men. Not that prostitution is limited to the working class; but quite a large percentage of the patronage of the houses of prostitution comes from the young workers. They can hardly be blamed. Here they are, working all day, sweating over some monotonous, uninteresting job, under a constant mental and nervous strain. What more is to be expected than that the young fellow will go the limit when he is free, in order to lose himself? Not having the ability to dose himself with intellectual opium, as “tired radicals” and such people do, he simply gratifies all his animal desires. This is partly an explanation also, of why prohibition has never worked in the city. The worker can always drown his bitter memories in hooch. In order to live, the worker simply has to forget the machine; and the only way he can do that is through wine and women.

Exhausted Workers

The other outstanding social result is the difficulty of labor organization. In the first place, when the workers finish a day’s work they are tired. I have gone out with Ford workers going to the afternoon shift. Over the whole street car there was an air of animal tiredness; the men were beaten, and they knew it, and they did not care so much. After all, they were simply machines. I have also come home with Ford workers at midnight. Then there are two kinds: one group which is fatigued, tired of life and all that it implies; they are listless and bored, with dull eyes and dead, white faces; another group, tired and angry, ready to take offense, snapping and snarling at all around them—just another expression of that same physical weariness which makes you indifferent to everything except rest and sleep. You can’t talk to men like that about organization, for that would drag in the machine, and they don’t want the machine; and it would involve danger and blacklisting — and they prefer their twenty-five dollars a week to nothing at all. In the factory itself there is no chance for personal contact, as I have explained elsewhere in these articles, so that propaganda cannot be carried on inside the plant. As a result, this whole organization problem is one which baffles even the most enthusiastic radical.

These articles were not intended to be exhaustive; they have merely served to expose some of the more obvious falsities of the Ford propaganda. This situation is but one of the whole exploiting machinery built up in this city, for every plant is rapidly following the example of Ford in speed-up and wage cutting. General Motors, now intensifying its competition with Ford, is carrying on a gigantic price-cutting campaign, and the workers have to pay for this in lower wages. Ford, in order to keep in competition, has to follow suit. In both cases, the worker is left holding the bag. At this time, the inevitable result of such policies is just coming to the fore. Never in all my contacts with workers have I seen such seething discontent as has been brewing in the last two or three months. The call for organization of the auto workers is not only now more urgent but more strategic; this city, stronghold of the “American Plan”, is the logical point of attack. Ford, above all, stands out preeminent in this shameless exploitation of the wage-earners; he employs over a hundred thousand workers. Attack ‘him and you attack the rest. The whole situation demands the stopping of this damnable slaving of men. Auto Workers, unite!

Labor Age was a left-labor monthly magazine with origins in Socialist Review, journal of the Intercollegiate Socialist Society. Published by the Labor Publication Society from 1921-1933 aligned with the League for Industrial Democracy of left-wing trade unionists across industries. During 1929-33 the magazine was affiliated with the Conference for Progressive Labor Action (CPLA) led by A. J. Muste. James Maurer, Harry W. Laidler, and Louis Budenz were also writers. The orientation of the magazine was industrial unionism, planning, nationalization, and was illustrated with photos and cartoons. With its stress on worker education, social unionism and rank and file activism, it is one of the essential journals of the radical US labor socialist movement of its time.