A classic. Theresa Malkiel reporting on a world she knows as well as anyone as 100,000 largely immigrant clothing workers strike ‘for the right to live’ in New York City and across the country during the winter of 1913.

‘Striking for the Right to Live’ by Theresa Malkiel from The Coming Nation (Girard, Kansas). No 124. January 25, 1913.

GRANDMOTHER! what are you doing here?” I asked of an old, old Italian woman who came up panting to the fourth floor of Clinton Hall. She turned around, looked me over with her black, penetrating eyes, which in spite of her age had not lost their luster and said:

“Me striker. Who you are?” I showed her my speaker’s card issued by the joint committee of the Socialist party and the United Hebrew Trades and she nodded her head in approval. I told her I was anxious to hear the story of the strike from the lips of the workers themselves.

“Me no speak much English,” she replied, “but me tella you just what me feel.”

She pulled up her gray, worn shawl which had slid down from her bent shoulders, smoothed her snow-white hair and slowly in broken English told me her tale of woe and suffering.

As she talked on I observed her closely and wondered what had kept up the fire and activity in that aged body, perhaps her very sorrow and unbelievable struggle for existence, for the revelations made by these aged lips sent a chill through me, filled my heart with horror. I knew that her case was not singular, that her condition was characteristic of the condition of all of her sisters in the trade and they constitute 60 per cent of the entire number of 15,000 women workers in men’s and children’s clothing industry.

She told me of twenty long years spent in the clothing workshops where the air is constantly surcharged with the foulest odors and laden with disease germs, she complained of the lack of sunlight of which she had so much in her own land. Here she had to spend her days working by artificial light. She complained of the long hours when work was plentiful, of the dread of slack time, of the small wages at best.

A bread winner for her own children in her younger days, when she first came to this country, she was now supporting two grand-children whose mother fell a victim to the ravages of consumption. Consumption invaded the old Italian woman’s family, as it had invaded the families of most of the clothing workers, carrying them off in the prime of life. The old woman was exceptionally strong, and she and the two small children she was supporting were the only survivors of the whole family.

These children, who are the apple of her eye, she keeps in a two-room flat of a rear eight-story tenement house located on East Houston street, the district where most of the clothing workers lived in order to be near their workshops, and where the population is recorded to be 1,108 to every acre. She pays $8 a month for rent and keeps two boarders to help pay it.

Strike for Love of Grandchildren

This woman who lacks only five years to the allotted three score and ten must finish 20 pair of pants, that is, sew on the lining, serge the seams, finish up the legs, sew on buttons and tack the buttonholes in order to make a dollar a day; $6 a week is the highest she ever makes in season. The season in the clothing industry lasts from March to June and from September to December. The old woman is no exception, to the rule, $6 per week, in fact, is above the average, many make less and very few more. They have no regular hours, but work as long as there is work, sometimes twelve, and fourteen hours a day.

It was not herself that the old Italian woman considered so much, as her poor orphan grand-children who had to take up the trade where she would leave it off.

“Why me strike you ask?” all the venom of the years of sorrow and wretchedness, all the bitter memory of her sacrificed children, cried out in her voice of defiance.

“Me strike because everybody strike, me all wanta live, me, too, lova me childs.”

“Union all right! me stick to union,” chimed in another worker.

“Me sick of the boss, me sick of work, me sick go hungry most time. Look!” and she showed me the little finger of her right hand. The bone was worn, the finger twisted into hook shape.

“Cotton, cotton, all the time, cotton I keep on this finger for 16 years, for 16 years me make buttonholes by hand. One hundred and fifty a day, when me want to make $1.25. Me work quick, quick like one steam engine. Me bite, bite, bite, look!” she opened her mouth. Her front teeth were completely worn out and decayed.

Teeth and Buttonholes

“You see, you no understand. Every buttonhole me make me must bite together with me teeth, me must do this quick, quick so look nice and no take too much time, me can no spare time when work is busy. My eyes they hurt, me can no see much now. Me sick, me tired, me can stand no longer, that’s why me all strike.“

I listened to her and thought of the billions of germs which are daily transmitted into our garments from the mouths of sick workers. A shiver went through my body, the fate of the Nation under these conditions was simply appalling, but the immediate surroundings were even more so, and my thoughts went back to the poor miserable garment workers, victims of greed and exploitation who, maimed, and distorted, and crippled had yet to drag on their miserable existence.

“She is perfectly right,” said a young Jewish girl. “There is no use, we simply had to strike, there was nothing else left for us to do. Look at me, I must finish 12 big coats in order to make a dollar a day, that is when work is plenty.”

“Nine cents, that’s what they pays us for finishing a whole coat, or overcoat sleeves, collar, buttons, lapels and all. I work like a slave and what have I from it? nothing. I am always in debt. When slack comes I must borrow to live on, the short season that’s really what is killing us. When the season starts in we work all the time day and night, we can’t earn much more than we need to live on and there are the old debts to pay. And those little bosses, the roaches as we call them, they simply skin us alive.”

Tailor by Inheritance

I left the group of women and walked over to a middle-aged Jew. You can find them all there; people of all nationalities, young and old, men and women, all spending their days and evenings devising means how to combat the enemy, making up future wage schedules, comparing union and nonunion conditions, thinking and talking of everything but their own hunger and suffering, that is, unless you bring out the conversation.

The Jew, whose long beard and care-worn face made him look much older than he really was, told me with pride that he was ‘a Schneider fon zu house’ which means that the tailoring industry was in the family for generations. Not here, in free America, but out there in darkest Russia, where he dealt directly with the customer and had no boss over him.

His wages averaged $10 a week which is the average wage for the male hand workers. He had four children and a wife to support on this sum. What wonder that the burden of the working class subjection, the persecution of his unfortunate race expressed itself in the sorrowful eyes, in the wrinkled forehead, the bowed shoulders? What wonder that he impressed me as though he had no more energy left to fight, that he was not the kind to stick.

AND yet he was ready to stay out to the end. He was used to it, he said. Last winter he was laid off for eighteen weeks. He managed to pull through, or rather starve through.

“Perhaps,” said he raising his eyes, “the good Lord will take mercy on his long abused children, the tailors, perhaps he will better their condition a bit, but they must help Him, they must strike, they must ask, they must demand.”

The very life-blood in his veins and in the veins of his fighting co-workers seems to be the heritage of bygone ancestors who thousands of years ago fled from slavery and bondage to a better land. The spirit of rebellion, the determination to fight which permeates the emancipated, exhausted Jewish tailors is simply wonderful and makes one think of the thousands of years of wandering and persecution and the Hebrew perseverance to seek ever better conditions to stand in the foreground of all revolutions for freedom.

Ten Thousand Pickets

A tumult, a commotion, a shout and I found myself eagerly peering out of the window; many heads pressed close about and in back of me. They were coming from the field work, the pickets I mean. Not two, not ten, not a hundred, but 10,000 strong, an army of labor, a city in itself.

My God! how powerful they looked. Every stone in the street pavements, every brick of the dark grim tenements seemed to have spoken to me of it. I was moved to tears of joy. I felt like a long-lost traveler who had at last found the right road. Now I knew it. There is where the true power, the road to freedom, was to be found in the combination and solidarity of labor.

These ten thousand tailor pickets were a power that even New York could not combat. It would take the entire police force to fight them man to man, or rather man to woman, for the women are really the greater fighters, the most determined pickets of the two.

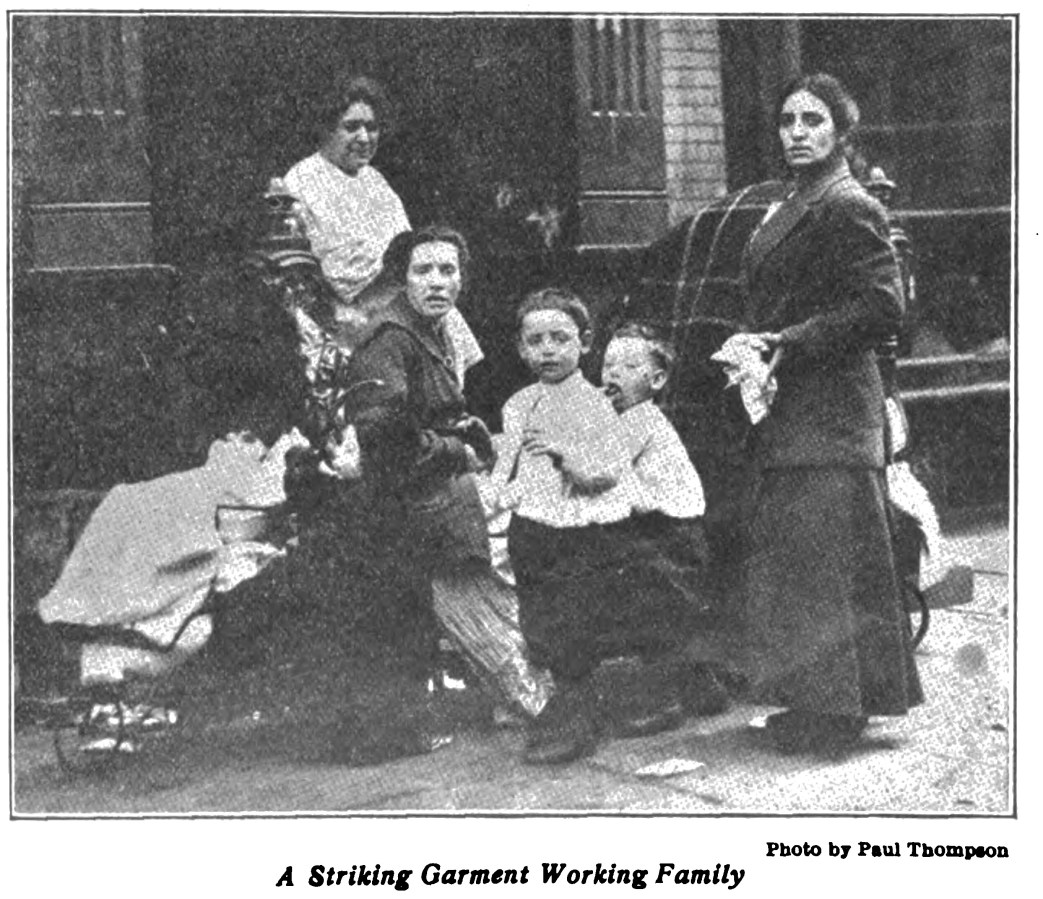

Out of the picket line came an Italian woman, a mother of six children. She was beaten up by the police while watching her shop with a few others. The brutal thugs in police uniform knocked her about, bruised her face, disheveled her hair, tore her clothes off her back and Lord knows what else they might have done to her had she not been rescued by the army of 10,000.

Thus is the working class mother treated by our capitalist government, for no other crime than the earnest desire to earn an honest living for her children.

She took it calmly, stoically, as they all take it, the true Roman matrons that they are. “It’s all for my childs,” she said. “I fight them again. I no care.”

And still the picket line marched onward like a threatening cloud from above. They feared nothing, not even the elements. Occasionally one would fall out of their midst for the same reasons as the Italian woman came out of the picket line, but the men, like the women, took the medicine dealt out to them by the police and thugs like good fellows.

There was Sam Spilka, who got a needle stuck into his eyelid by a mean, low cur of a boss. His face was swollen, his eye all bandaged up. But Sam pointed smilingly at it, “it’s my badge of honor.”

“I wish I was young, I’d go with them, too,” said old Mr. Simkovitch following the passing lines. Mr. Simkovitch said he was “a presser by pants,” he got $6 a week in season, but he and his wife had to live on the money earned during the season the whole year round. Theirs wasn’t much of a life, he said, but his old woman agreed with him that the tailors had to go out on strike, for they were starving anyway. He and his old woman were ready to stick by the strikers as long as the fight would last.

The Fighting “Forward”

Going out of Clinton Hall I moved along with the picket lines toward Rutger’s Square, or the Forward’s Square as it may be more rightfully called. For the Jewish Daily Forward, with its new twelve-story building, is really the central point of gravitation for the entire East Side. Every inch of ground on the Square was taken up by men, women and children. All strained their eyes and ears trying to listen to Alexander Irvine who was speaking to them on behalf of the Socialist party. The fact that they understood but little English seemed not to matter. He was speaking in the name of the Socialist party and the Forward he was their friend.

It was hard work to wedge one’s way through to enter the Mecca of the strikers, the Forward building. Strikers to the right of me, strikers to the left of me, strikers all around me. Every room, every corner, every nook of the twelve-story building was filled with strikers, thousands of bodies, with what seemed to be but one great soul, one hope to win the fight.

I spoke to Chernenko, a big stalwart Russian, he ironed coats 14 hours daily in the season, and got $12 per week. His money, like the money of all the garment workers, had to last for the year.

Eight months’ earning for twelve months’ existence. He said he had starved enough in Russia; he left for he could not stand it any longer; he would not put up with the despotism of the Tzar, nor was he going to stand for that of his boss Shamansky. Mrs. Heinrich, a good-natured German housefrau said that vests, or the finishing of vests, paid by far less today than it did five years ago. She was getting older, there was no prospect of her ever leaving work until her dying day, and she’d better stay out with the rest and get better wages, shorter hours and work in a decent place.

“Brothers and sisters,” came the voice of the beloved leader, Max Pine, a good, red-blooded Socialist. “Our strike is the seed of a new life, the life of brotherhood and solidarity of labor.” His voice was drowned in a storm of applause.

“This is a new issue,” he continued. “We no longer fight single-handed. We are one body, one soul. This is an entirely new issue which confronts our bosses at present. They have brought us to it through their heartlessness and unmerciful greed, and now that the long hoped for miracle, the affiliation of the entire industry has happened let us be thankful to them.“

Discovering of Solidarity

Pushing and shoving and straining every muscle of my arms I managed to get out into the open once more and slowly work my way down the street to Canal and from there to the Bowery. All traffic was made almost impossible by the thousands of striking men and women most of whom were congregated in an area of twenty city blocks. Up the Bowery amidst the derelicts of the twentieth century I went to Beethoven Hall, where the 6,500 striking clothing cutters make their headquarters. There, like everywhere in the strikers’ headquarters, everything buzzed with life and animation.

“It goes without saying that we must stick together,” said Mr. Green, a presentable looking American gentleman who happens to ply the trade of clothing cutter.

“As a matter of fact, we all depend upon each other,” he acquainted me with the wonderful discovery, then added in a low voice:

“Would you believe it, it is getting as hard for me to make ends meet as it is for those poor devils of foreigners.”

The statement of one of the strikers is practically the statement of all. They are fighting for a chance in this world, for the right to live. They love their children even like we love ours and they want to be able to do what is right for them. “I see my children, or rather they see me only on Sunday. They are asleep when I go to work at half past six in the morning and are asleep when I come back from work at ten o’clock at night,” a custom pants maker told me.

Nine Dollars a Week

The man was unusually pale, dark blue rings encircled his sunken eyes, his hands were thin, emaciated. I knew he would not live to see his children grown. He had two of them. What would happen to the little tots? The tailor had saved nothing for a dark day, how could he his wages averaged $9 per week, he could scarcely keep body and soul together on that sum in the city of New York.

And yet $9 is the average wage made by the male hand workers in trade. It must be remembered that the majority are married and have families to support. What wonder that their struggle for existence had reached the limit?

In the mass rebellion of the 125,000 men and women each individual garment worker sees a possible chance for redress and finds an outlet for his accumulated wrath.

The tailor, though “his soul may have grown as thin as a needle,” wants to protect his children. He is tired of seeing them hungry most of the time, half naked, herded together like cattle in small, dark, dirty quarters, which capitalist society calls a home. His heart aches to see them die like so many flies. In the tenement district where most of the garment workers live, of every nine babies born, one dies before it is five years old.

The garment workers were driven to the present strike. The wages in the entire industry have not been raised for a number of years, although the making of the garments has become more complex. The tailor’s cost of living, like that of everybody else, has soared sky high. The tailors are a patient lot, their very work makes them so. They held out to the very last, but when the lines of exploitation were overdrawn, even the tailor’s limit of endurance came to an end. The bit was broken, the reins fell apart and like the proverbial mule, the garment worker balked. Not as an individual, not as a member of his certain trade, or his branch of the trade, but the whole industry, or to be more exact 85 per cent of it.

The Jews, Italians, Lithuanians, Germans, Russians, Letts and the few Americans, from the most skilled mechanics to the least trained button sewers all broke loose like a cloudburst on a summer’s day.

Like sheep in a field at the sight of a wolf they flocked together and for the first time in the history of the labor movement in the United States, made common cause.

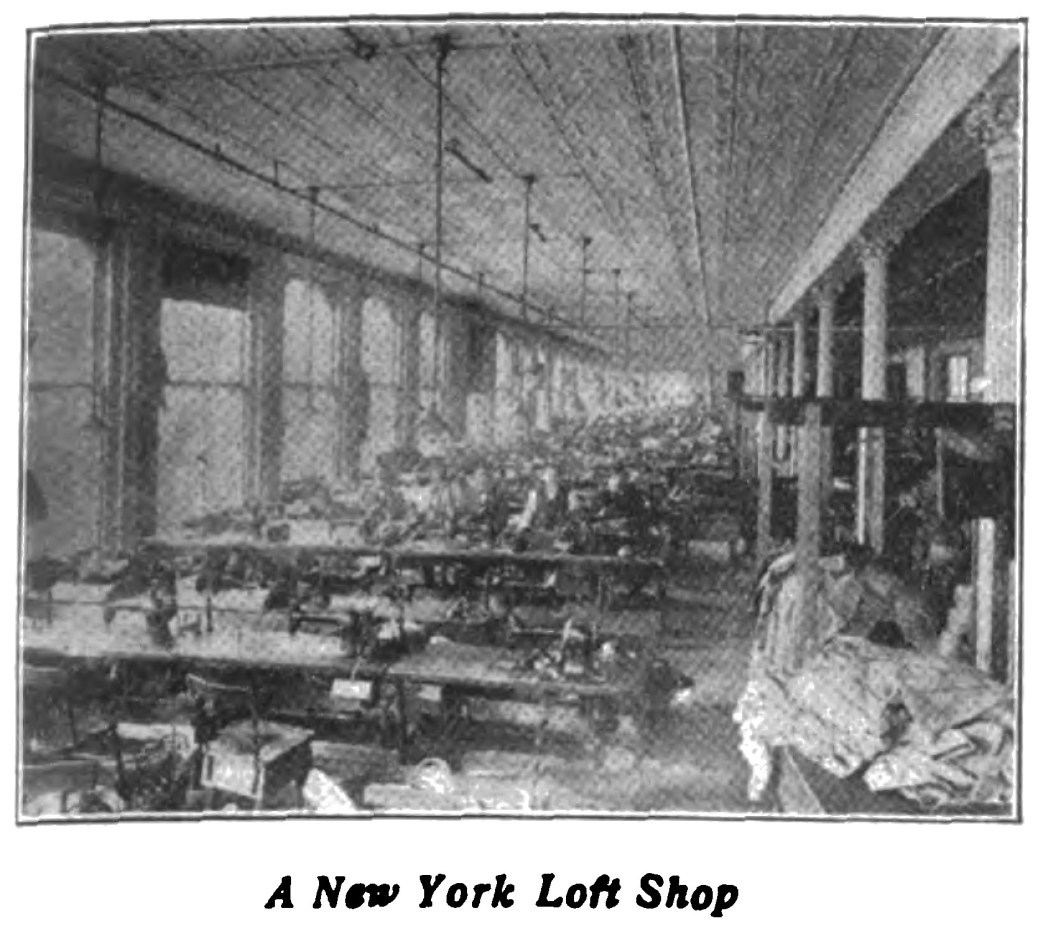

Danger stared them all in the face, the instinct of self-preservation led them to co-operation. The cutters, who have heretofore been the aristocrats of the industry, found to their great dismay that they were no longer safe, no longer sure of a job. The clothiers employ now-a-days two expert mechanics while the rest of the force of twenty, or twenty-five cutters are young boys who work for a mere pittance, yet do most of the work formerly performed by skilled cutters.

The coat makers, the second in line, found that women were fast being enlisted to do their work at half the price paid to men, that the work given out to the sub-contractors was done for less than the women did it for, that the brief seasons were getting ever briefer. This because the clothing manufacturers no longer make up stock. Former seasons of over production have taught them a lesson. They get their orders now simply from the samples of material and make up only as many garments as are ordered.

The vest-makers are now worse off than ever. Since people stop wearing vests in summer the season lasts only about four months in the year, the rest of the time the vest-makers are mostly idle. The influx of women into this branch of the trade, has cut down the prices. A vest maker is hired for as little as the boss can get him to take.

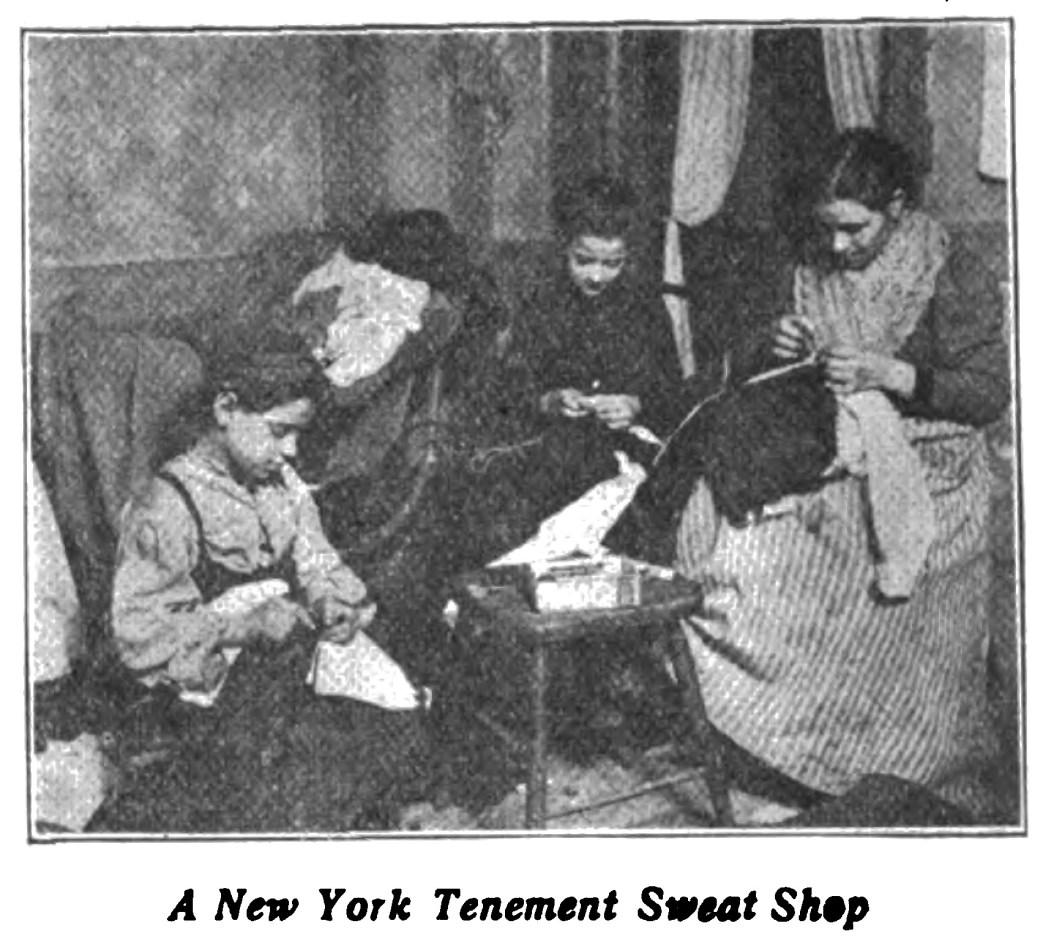

The pants makers, the worst paid workers in the entire industry have always been on the verge of starvation. Their condition is beyond description. They are still at the mercy of the subcontractors who suck the very marrow out of their bones. They work in fire traps, where the broken wooden stairs are usually built around a wooden hoisting shaft which acts as a conductor of smoke and flames. Their shops are dark, dirty; the plumbing is out of order, the hours are most unearthly.

The children’s jackets, knee pants and overcoat makers are paid even less than the workers at men’s clothing. Their complaints are constantly heard, winter and summer, in season and out of season.

As a matter of fact, the clothing industry is from its very inception linked with low wages, long hours, unbearable working conditions. The home work, the small shop system, the great subdivision of labor, which meant the use of unskilled labor were responsible for it from the very start.

The clothing workers have suffered and starved, and, it must be admitted, tried to improve their condition by frequent strikes and attempts at organization. But their organizations, even as their strikes bore local character. One part of the trade, or one branch, or subdivision would go out on the warpath, but its struggle was doomed from the start, for the rest of the industry continued its work as if nothing had happened.

The German hated the Jew, the Jew the Italian, who is trying to wrench the trade from him, the Italian despised the Russian, the Russian the American, the cutter looked down upon the operator, the operator exploited the finisher, the finisher the helper, and while this was going on the employers exploited them all to their heart’s content.

The United Garment Workers of America, though considered the mother body of the clothing trade occupied themselves chiefly with one branch the overall-making, which is mostly in the hands of American women, and paid but little attention to the woes and sorrows of the tailors, perhaps, because the latter was considered beyond redemption.

Thus have men, women and children slaved for over seventy-five years. Thus have thousands upon thousands gone to their early graves, victims of consumption, heart disease, malnutrition, insanity. The man in charge of the claim department of the Workingman’s Circle, most of whose members are garment workers, told the writer that nine-tenths of their members died before they reached the age of forty.

And with the tailors the general public suffered. Unsanitary work-rooms, sweat-shop labor means infection of the garments, and eventually of the public who wear them. Our coats and suits were and still are made in places where smallpox, scarlet fever, diphtheria, measles, consumption and numerous other contagious diseases make great inroads. Our garments are made by workers themselves afflicted with disease, as a matter of fact, the workers in the sweat-shops and tenements not only work on the garments we wear, but often use them to sleep on or to cover themselves with.

Thus have ninety-two million people all over the country been subject to disease and contagion carried to them in their garments from Baltimore, Philadelphia, Chicago, Rochester and New York. For these cities produce 70 per cent of the entire output of man’s and children’s clothing, while New York alone produces one-third of the entire output.

New York was always the largest center in the clothing industry. The city has the natural advantages for production of all grades of clothing. Here, too, a large body of tailors land from Europe, and for the most part remain. The tailors form the nucleus for the better grades of work, while the hundreds of thousands of immigrants landing here yearly enable the employers to obtain cheap labor for the lower grade of garments.

The 125,000 striking garment workers think and say that their strike should be the concern of the entire nation. That their demand for the abolition of the sweat-shop and the subcontracting system should meet the endorsement of every thinking man and woman.

As a matter of fact, even the capitalist press, always ready to slur labor and denounce strikes has exhibited a more human attitude in this strike. It has gone even so far as to express its approval of the abolition of the sweatshop, this perhaps, not because it loves the garment workers so much, but that it wants to protect the general public more.

Then again the sudden display of solidarity has almost taken our newspaper men off their feet. And how wonderful this display is at present can be fully appreciated by an eye witness only. From the highest to the lowest, the few Americans as well as the great body of foreigners, the bulk of Jewish men even as the Italian women stand out for the recognition of their union, for the joint settlement with all branches

“When did the tailor learn this class solidarity? How did he come by it?” ask our upholders of the present regime. They know not, or don’t care to know that the world moved a bit of late, that the progress of evolution, the age of industrialism has advanced the cause of the working class. That the workers are not only firmly-planted on the economic field, but that they have a great political party, the Socialist party, that they have a great press in almost all languages represented in the tailoring industry, the Socialist press.

The part played in this struggle by the Socialist Jewish Daily Forward will undoubtedly go down into the annals of the history of the labor movement of America. It was the Forward which has first brought pressure to bear upon the United Garment Workers Central body to take the tailors seriously. It was the Forward which has for the last decade played the role of chief and only educator among our Jewish workers, who are, after all, the foundation of the industry. The Forward has in time become the strongest Jewish organ in the United States and with rising glory came the uplift of the Jewish masses as well. The Forward articles and editorials have always dealt with the relation of capital and labor; class solidarity and class consciousness have always held the foremost place on its pages.

The United Hebrew Trades in Greater New York have likewise had a hand in educating the workers to their present status of class consciousness. In fact, the United Hebrew Trades and the Jewish Daily Forward are the protecting force of the Jewish Working men in New York and vicinity. Their very name carries weight, their advice is heeded, their displeasure feared.

It must be remembered that these bodies are closely affiliated with Socialism. Socialism is the most predominate feature of this strike. The Socialist party of Local New York has thrown its entire force into the ring, as it has never done before. In conjunction with the United Hebrew Trades the party has established a speakers’ bureau and the speakers who are sent to speak and work with the one hundred and twenty five thousand garment workers are all Socialists with few exceptions. Socialist committees are working day and night in various directions, and though the party does not attempt to direct the policy of the strike, it stands ready to remain with the strikers until the battle is won. The party membership is ready to fight for them, to beg for them, to share with them.

But it is not the Socialist party, not the Daily Forward or the United Hebrew Trades who will win the strike for the garment workers. The strikers will win it themselves with and through their own efforts and for themselves.

The brutality of the police, the one-sided decisions of the judges only serve to arouse their enthusiasm. In this strike, like in the shirt waist and cloak makers strikes the men and women go to prison for their cause willingly and cheerfully. They are prepared for the worst, even for a long siege.

Theresa Malkiel (1874-1949) Theresa Serber was an American born in Ukraine into a large Jewish family. In 1891 the Serber family emigrated to New York City’s Lower East Side where a teenage Theresa found work, like so many Jewish women of her generation, in a garment factory. Still a teen, she joined the Russian Workingmen’s Club and in n 1892 she began her organizer’s life helping to found the Infant Cloakmaker’s Union of New York, becoming its first president. In 1893 she joined the Socialist Labor Party and representing her union in the Socialist Trade and Labor Alliance. In 1899, Theresa joined the ‘Kangaroos’ opposed to Daniel De Leon’s leadership and became a founding member of Socialist Party of America, and the first working class women to rise to leadership of the Party. In 1905, Malkiel organized the Women’s Progressive Society of Yonkers, a branch of the Socialist Women’s Society of New York. The ‘separatism’ of the Society was opposed by the male leadership. Malkiel was one of the best-known women Socialist writers of the ‘Debsian era’ with articles in many union, labor, feminist and socialist publications. Malkiel was elected to the Woman’s National Committee of the Socialist party in 1909 and led the establishment of Woman’s Day, starting on February 28, 1909, which would inspire International Women’s Day.

That year also saw the epic New York City shirtwaist strike in which she would play a leading role with the Women’s Trade Union League. In 1910, Malkiel’s most lasting work, The Diary of a Shirtwaist Striker, a fictionalized account of the shirtwaist strike was published and widely read. Malkiel also helped to raise the question of race in the Party, challenging the Socialist’s internal segregation and racism and writing a scathing report on the life of the Party after a 1911 speaking tour through the South. A leading Socialist campaigner for the vote, in 1914, she headed the Socialist Suffrage Campaign of New York and was on its National Executive Committee to travel across the country campaigning for suffrage. Malkiel stayed with the Part during the disastrous 1919 splits, and ran for State office in 1920. Her partner was leading Socialist solicitor Leon A. Malkiel. Although Theresa was able to move from a life of factory work, she remained committed to workers organizing and education, leading immigrant and adult classes for workers in Yonkers for the remaining decades of her life.

The Coming Nation was a weekly publication by Appeal to Reason’s Julius Wayland and Fred D. Warren produced in Girard, Kansas. Edited by A.M. Simons and Charles Edward Russell, it was heavily illustrated with a decided focus on women and children. The Coming Nation was the descendant of Progressive Woman and The Socialist Woman which folded into the publication. The Socialist Woman was a monthly magazine edited by Josephine Conger-Kaneko from 1907 with this aim: “The Socialist Woman exists for the sole purpose of bringing women into touch with the Socialist idea. We intend to make this paper a forum for the discussion of problems that lie closest to women’s lives, from the Socialist standpoint”. In 1908, Conger-Kaneko and her husband Japanese socialist Kiichi Kaneko moved to Girard, Kansas home of Appeal to Reason, which would print Socialist Woman. In 1909 it was renamed The Progressive Woman, and The Coming Nation in 1913. Its contributors included Socialist Party activist Kate Richards O’Hare, Alice Stone Blackwell, Eugene V. Debs, Ella Wheeler Wilcox, and others. A treat of the journal was the For Kiddies in Socialist Homes column by Elizabeth Vincent.The Progressive Woman lasted until 1916.

PDF of full issue (large cumulative file): https://books.google.com/books/download/The_Coming_Nation.pdf?id=IMksAQAAMAAJ&output=pdf