‘Lenin and the American Negro’ by James S. Allen from The Communist. Vol. 13 No. 1. January, 1934.

Lenin was forced to give special attention to the national question because of all the obstacles put in the way of the creation of a real internationalist Bolshevik Party by the Czarist Empire, “the prison of nations” as he termed it. The fact that Great Russia oppressed a whole series of weaker nations, where, as in the home country, the bourgeois-democratic revolution had not yet been completed, made the task all the more difficult, gave rise to all kinds of deviations towards bourgeois nationalism within the Parties of the oppressed nations and towards Great-Russian chauvinism within the working class movement of Russia proper. In Lenin’s approach to and solution of these problems we should therefore find an answer to the vexing, although less complicated, problems facing the Communist Party of the U.S.A. as a result of the imperialist oppression of the colonies and the American Negroes. Space, however, will not permit us even to venture a comprehensive exposition of Lenin’s views on this problem. We will only touch upon two aspects of Lenin’s teachings which are of special significance at the present time, particularly in connection with the Negro question.

THE RELATION OF THE NATIONAL QUESTION TO THE PROLETARIAN REVOLUTION

For the benefit of those who fail to see the connection of the development of the proletarian revolution in the United States with fighting for equal rights for Negroes and for all the democratic demands raised in the struggle for Negro liberation, including the right of self-determination, it is well to recall Lenin’s position on the relation between the national-revolutionary and proletarian movements. As Marx and Engels considered every national movement from the point of view of the destruction of feudalism and the advance of the working class movement, Lenin weighed every national-revolutionary movement from the point of view of the overthrow of imperialism. Today imperialism has penetrated every nook of the earth, no matter how remote, and implanted capitalist relations in one form or another upon a patriarchal or feudal soil. At the same time, however, it has given to the national-revolutionary struggle not only the object of destroying the pre-capitalist relations, but of overthrowing imperialism at one and the same time.

In the penetration of the colonies and their complete division among the powers, the reactionary imperialist bourgeoisie has allied itself with the native patriarchal or feudal class in the struggle against the national revolution. Imperialism has, therefore, given to the proletariat of the oppressing countries, a powerful ally in the national-revolutionary movement of the colonial and semi-colonial world.

In his polemics against the deviations of the Polish Social Democrats on the national question (“The Discussion on Self-Determination Summed Up,” 1916), in which he gives them a sound thrashing for their annexationist, anti-self-determination position, Lenin drives home the very core of the problem:

“Just precisely in the ‘era of imperialism’, which is the era of incipient social revolution, the proletariat today supports with all its power the rebellion of annexed territories so that tomorrow, or simultaneously with the rebellion, it may attack the bourgeoisie of the ‘great power which is weakened by that rebellion.”

And Lenin points out that since 1898, the year of the Spanish-American War, which roughly marks the beginning of the world imperialist era, Czarism, against which Marx and Engels had directed their main fire, had ceased to be the chief bulwark of reaction. Whereas formerly the socialist movement “was first of all against Czarism and for the revolutionary peoples of the West forming big nations”, at present it is “against the united front of the imperialist nations, of the imperialist bourgeoisie, of the social imperialists, and for utilizing all national movements against imperialism for a social revolution”.

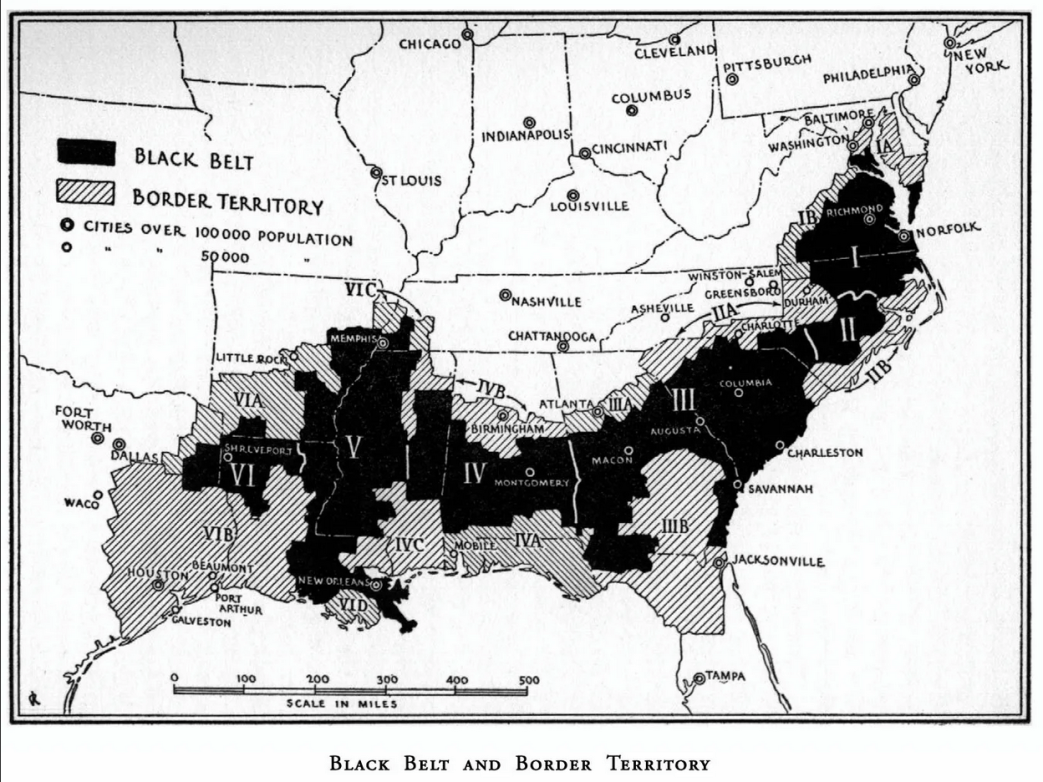

Lenin viewed the national question from the point of view of the development of the proletarian revolution. His main perspective is the weakening of world imperialism and he therefore supports every serious revolutionary movement which acts in that direction, as a prerequisite or as a simultaneous condition for the direct attack of the proletariat upon the bourgeoisie. And one of the most vital points for attack in U. S. imperialism lies precisely in the Black Belt, where the remnants of slavery and imperialist oppression have created the sharpest antagonisms, where the Negro question throughout the country has its roots.

Lenin wrote the above-quoted passage in a polemic against the Polish comrades, who, in their reaction against bitter Polish bourgeois nationalism, went to the extreme in demanding that the Russian Bolsheviks should drop from their program the slogan of the right of self-determination for Poland. The Polish comrades thought that the slogan of the socialist revolution must not be covered up by the national question. How often has this argument been repeated, how it has persisted, despite the continual warfare against this dangerous deviation by Marx and Engels and again by Lenin!

It is to be found in smart American trappings in the Socialist Party position that the “Negro question is a pure labor question”; in the Lovestoneite dress and petticoats of “caste and class” which are, however, transparent enough to reveal the essential Social-Democratic body; in the opinion but recently expressed in our own ranks by a responsible Party newspaper that the Negro question is fast becoming but a “pure class question”.

Lenin has no patience with the pedants of “pure proletarian revolution”. In a special section of the article quoted above, devoted to the Irish Rebellion in 1916 and the views of Radek, who partook of the Polish Social-Democrats’ mistakes, Lenin berated him roundly for his “contemptuous attitude towards the national movements of small nations”. (Those who turn up their noses at the Cuban revolution and think that a Soviet movement there is doomed to ignominious failure, please take note!) Radek had attempted to pass off the Irish Rebellion as a “putsch”. This was quite in line with the denial by Rosa Luxemburg and the Polish comrades of the ability of small nations oppressed by imperialism to put up any active opposition to imperialism, and, consequently, the uselessness for the proletariat of supporting such national movements. After pointing out the rebellions during the first two years of the imperialist war among the Indian troops in Singapore, in the French Annam, the German Cameroon, among the Irish and among the Czechs, Lenin wastes no words in declaring that anybody who calls such a revolutionary movement as the Irish rebellion a putschk “‘is either a bitter reactionary or a doctrinaire, hopelessly incapable of imagining a social revolution as a living phenomenon”.

“For,” he points out, “to think that a social revolution is possible without rebellions of small nations in the colonies and in Europe, without revolutionary explosions of a part of the small bourgeoisie with all its prejudices, without a movement of the nonclass-conscious proletarian and semi-proletarian masses against feudal, ecclesiastical, monarchical, national, etc., oppression—to think that way is to give up the social revolution. . . .

“Whoever is looking for a ‘pure’ social revolution, will never live to see it. He is a revolutionist in words only, but does not understand the real revolution.”

In these few lines Lenin concentrates his whole “wrath” against those comrades whose doctrinaireness blinded them to the mighty sweep of the proletarian revolution. And his words apply with equal force to those comrades who today—despite the numerous indelible lessons revealed by the sweep of the October Revolution, despite the daily and growing testimony of the revolutionary character of the struggle for Negro liberation in the United States, for real self determination in Cuba, the Philippines, etc.,—fail to understand that the revolutionary proletariat must forge this link in its day-today agitation and activities. Scratch a “pure” revolutionist on the Negro question and you are sure to find a white chauvinist. And what, indeed, is more “revolutionary” than to excuse oneself from the pressing and growing demands of the struggle for Negro liberation and of the independence struggles in the colonies, than to cry “revolution”?

The struggle of the Negro people for liberation from the yoke of American imperialism is precisely of that character which makes the proletarian revolution not “pure” and “restricted”, but broadens its scope, brings to it a tremendous reservoir of revolutionary energy. In one of the polemics which Lenin undertook in 1916 against those “Marxists” who objected to Paragraph 9 in the program of the Russian Party in regard to self-determination, (“About a Caricature of Marxism and About ‘Imperialist Economism”) he states:

“The social revolution cannot come about except as an epoch of proletarian civil war against the bourgeoisie in the advanced countries, combined with a whole series of democratic and revolutionary movements, including movements for national liberation, in the undeveloped, backward and oppressed nations.”

He points out further that:

“National oppression of any kind calls forth the resistance of the broad masses of the people; and the resistance of a nationally oppressed population always tends towards national revolt.”

LENIN AND THE AMERICAN NEGROES

The ferocious oppression of the Negroes in the United States is calling forth greater and greater resistance from the broad masses of the Negro people, and this resistance is fast becoming one of those “revolutionary movements” tending towards national revolt. Lenin considered the Negro liberation struggle a movement of this character. The passage in the Theses of the Second World Congress is already well known here in which he speaks of the necessity “to support the revolutionary movement among the subject nations (for example, Ireland, American Negroes, etc.) and in the colonies”. Lest someone venture to argue that this reference to the American Negroes as a subject nation in the context of a political and, consequently, thoroughly thought out document on the national and colonial question, may have “slipped in”, let us recall the following facts.

Well in advance of the Congress, Lenin submitted his Theses on the colonial and national question to leading comrades. He attached a memorandum to the documents asking “those comrades especially with concrete knowledge of one or another phase of this very complicated question” to give their opinions and make their suggested corrections. He also asked them to give concrete data and experiences on a number of oppressed nations and colonies. He lists 15 of these oppressed nations and colonies about which he wanted the information. In this list (which included Austria, Polish Jews, Ukraine, Ireland, Balkans, China, Korea, Caucasus, etc.) there also appeared “the Negroes in America”. It could only have been after due deliberation that he singled out the American Negroes for special mention in the final theses.

It is very instructive also to recall what Lenin wrote about the Negroes in the South in his large work, New Data on the Laws of Capitalist Development in Agriculture: Capitalism and Agriculture in the United States of America. This work is concerned primarily, as the title indicates, with the extent and nature of capitalist economic relations in agriculture and with refuting the views of the bourgeois democratic economists on this subject. In order to do this he makes a detailed study of the development of agriculture in the United States, comparing it with agriculture in European countries. Lenin divides the United States for the purpose of his study into five distinct agricultural areas, of which the South is one. It should be kept in mind that Lenin was interested in this subject, not only to obtain a correct and comprehensive view of the development of capitalism, but particularly to apply this to the situation in Russia, where the bourgeois-democratic revolution was still‘on the order of the day. Let us first quote those passages from this work which have a direct bearing on the question:

“The United States of America, writes Mr. Himmer [a bourgeois economist], is ‘a country that never knew feudalism and has none of its economic survivals’. This statement is contrary to the facts, for the economic survivals of slavery are not distinguished in any respect from those of feudalism, and in the former slaveowning South of the United States these survivals are still very powerful. It would not be worth while to dwell upon the mistake of Mr. Himmer if it were merely that of a hastily written article. But the entire liberal and populist literature of Russia goes to show that the very same ‘mistake’ is made systematically and stubbornly with regard to the Russia share-cropping system—our survival of feudalism.

“…It is not necessary to elaborate upon the degraded social position of the Negro. The American bourgeoisie is not distinguished in this respect from the bourgeoisie of any other country. Having ‘freed’ the Negroes they took good care, on the basis of ‘free? and republican-democratic capitalism, to re-establish everything possible and do all in their power for the most shameless and despicable oppression of the Negroes.”

Citing the comparative figures for illiteracy as between the South and the rest of the country and as between white and Negro, Lenin continues:

“One can easily imagine the aggregate of legal and social relationships corresponding to this disgraceful condition in the field of literacy.

“What then is the economic foundation upon which this fine superstructure developed and is maintained?

“It is a foundation typically Russian, the ‘real Russian’ system of share tenancy, viz., share-cropping.

“More than that, we have here [in the South] tenants, not in the European sense of cultured modern capitalism. We are dealing here mainly with semi-feudal relationships, or, what is the same from an economic point of view, with the semi-slavery system of share-cropping…

“The share-cropping region, both in America and Russia, is the most backward region, where the toilers are subjected to the greatest degradation and oppression…The American South is to the ‘liberated’ Negroes akin to a prison, hemmed in, backward, without access to fresh air.

“…There is a striking similarity between the economic position the American Negro and that of the former serf of the central agricultural provinces of Russia.

“The anxiety of the Negroes to free themselves from the plantations over one half century after the ‘victory’ over the slaveholders is still proceeding with great energy.”

We have taken the trouble to quote these passages at length because this work is not yet available in English* and because here Lenin gives a penetrating and highly important analysis of the economic and social situation of the Negroes. In the above passage the principal points to be noted are:

1. The economic survivals of slavery are still very powerful in the South.

2. These economic survivals of slavery are “not distinguished in any respect from those of feudalism”.

3. This survival in the Southern states is the share-cropping system.

4. The system of share-cropping lies at the basis of the oppression of the Negroes.

5. The Negroes are in motion “to free themselves from the plantations”.

American bourgeois economists, historians and sociologists have shared in the mistake of Mr. Himmer in holding that society in the United States has never experienced feudalism. This supposed fact has been used by them as well as by some “Marxist” writers to explain away certain “baffling peculiarities” of American bourgeois society and the “backwardness” of the American working class. The absence of feudalism in any of its forms is supposed to have left capitalism free from any of the heritages of feudalism, permitted a fuller and freer development of democracy without the encumbrances of inherited economic and social antagonisms and thus permitted the working class a fuller measure of privileges and freedom than prevailed in European countries during the period of the growth and expansion of capitalism. As a matter of fact, however, the United States did experience feudalism to a comparatively late date (1865) in the form of the slave system, which was feudalism in a very high stage of development, having almost from its very beginning all the elements of rapid disintegration in the form of commodity production (cotton for the world market), but prolonged and stimulated by the very services it was rendering the growing industrial capitalism in the Northeast of the United States and in England. The production of cotton for the world market, within a feudal formation, with a correspondingly important role played by merchant capital, was bound to, and did, destroy the system which it nourished. And, as Lenin points out, just as the abolition of serfdom in Russia left powerful survivals in the form of share-cropping, the abolition of slavery also left powerful survivals in the South in the form of sharecropping.

A precise understanding of this fact is absolutely essential for a correct view of the development of American capitalism and its present process of transformation, and for an appreciation of the character of the Negro question, in particular, in all its ramifications. The principal reason that Lenin took such great pains to refute the bourgeois economists in the matter of agricultural development, and went so far afield to do it, was precisely that a correct analysis of these questions was absolutely essential to the working out of a correct policy for the Russian Bolsheviks in relation to the bourgeois democratic revolution. It was precisely on the basis of a comprehensive understanding of all the inter-relations of a society in which strong remnants of feudalism persisted side by side with the development of capitalism and an industrial proletariat that Lenin formulated the policy of the Bolsheviks during the Revolution of 1905 and later, under altered conditions, of the Revolution of 1917. As early as 1896, in his large work The Development of Capitalism in Russia, he was already belaboring the populist economists and historians for their contention that Russia never experienced feudalism in the sense that it existed in Western Europe. And the same mistake is made here, just as “persistently and stubbornly” in regard to slavery and the remnants of slavery.

It is necessary to point out that since Lenin wrote his work on American agriculture the situation in the Southern Black Belt has not been radically changed, despite the industrialization of the South and the migration of about one million Negroes into the North during and after the world war. The share-cropping system remains practically intact, still a powerful survival of slavery, bearing even sharper forms of antagonisms and even more potent with revolutionary eruption due to that very industrialization which was supposed by some to herald the vanishing into thin air of the share-cropping system and the Negro peasantry with it. This economic survival of slavery still remains the main basis upon which the oppression of the Negro people rests.

After pointing out the “most shameless and despicable oppression of the Negroes” and the nature of the South which for the Negroes is like “a prison, hemmed in, backward, without access to fresh air”, Lenin declares that the foundation upon which this superstructure of oppression rests is the system of share-cropping, “a foundation typically Russian”. We might add that the share-cropping system, the economic survival of slavery, serves also as the foundation for the oppression and persecution of Negroes in the North and West where they have in vain sought refuge from the prison of the South. And Lenin notes that a half century after the Civil War the Negroes are energetically attempting to free themselves from the plantation.

It was the realization by Lenin of the agrarian, bourgeois-democratic nature of the struggle that still had to be accomplished in the South that led him to characterize the American Negroes as a subject nation, that led him to apply the same general policy and tactic of the revolutionary proletarian party on the national and colonial questions to the struggle for Negro liberation. It is precisely the facts pointed out by Lenin in connection with his study of agriculture in the South of the United States that lie at the basis of the Party’s position on the Negro question, that form the core of the program of equal rights and the right of self-determination for the American Negroes.

Space has not permitted us to go into all of Lenin’s teachings on the national question, into the full breadth of his thought on this extremely complicated question. His teachings, based on the day-today problems that he and the Bolsheviks had to face and solve, encompass other aspects of the problem equally important, such as the role of the working class in both the oppressing and oppressed nations, bourgeois nationalism, the right of self-determination and separation, chauvinism, the role of the Parties of the Second International, the solution of the national question by the proletarian revolution as exemplified in the Soviet Union, etc., etc. His writings, in which are reflected and summed up the revolutionary experiences of the whole gamut of social development from feudalism to socialism, continue today to reveal new treasures, each richer than the other. They constitute the principal body of theory, policies and tactics, upon which we can draw to solve the numerous problems facing the revolutionary movement in the United States today.

There are a number of journals with this name in the history of the movement. This ‘Communist’ was the main theoretical journal of the Communist Party from 1927 until 1944. Its origins lie with the folding of The Liberator, Soviet Russia Pictorial, and Labor Herald together into Workers Monthly as the new unified Communist Party’s official cultural and discussion magazine in November, 1924. Workers Monthly became The Communist in March ,1927 and was also published monthly. The Communist contains the most thorough archive of the Communist Party’s positions and thinking during its run. The New Masses became the main cultural vehicle for the CP and the Communist, though it began with with more vibrancy and discussion, became increasingly an organ of Comintern and CP program. Over its run the tagline went from “A Theoretical Magazine for the Discussion of Revolutionary Problems” to “A Magazine of the Theory and Practice of Marxism-Leninism” to “A Marxist Magazine Devoted to Advancement of Democratic Thought and Action.” The aesthetic of the journal also changed dramatically over its years. Editors included Earl Browder, Alex Bittelman, Max Bedacht, and Bertram D. Wolfe.

PDF of full issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/usa/pubs/communist/v13n01-jan-1934-communist.pdf