Written while in his Soviet exile, this remarkable piece by William D. Haywood attempts to get Black and white workers to see their struggles in this country as part of one history, and with a common enemy. A section of a larger, unfinished, work, Haywood looks at the reality of United States as rooted in its colonial history of African chattel slavery and all manner of bonded and indentured European labor. Detailing numerous rebellions of the enslaved, Haywood places Black labor both firmly in the larger story of the U.S. working class, and the violent revolts against the system as struggles of labor.

‘We the People’ by William D. Haywood from Labor Defender. Vol. 12 Nos. 4 & 5. April & May, 1936.

When American working-men begin to think oi barbarous rulers and cruel oppression, their mental machinery slips a cog and runs back to bloody Jeffery, Torquemada, or Ivan the Terrible. They do not think of themselves or the terrible conditions that have always existed in America.

They shudder at the vision of rows of gallows with their dangling freight, but do they shrink as convulsively at the torture and lynching of Frank Little and Wesley Everest?

They can cast a mental picture of Ivan the Terrible as this insane monarch sat in a parapet of the Kremlin wall looking down into the Place of the Skull with eyes gloating as the knout cut into the quivering flesh of victims who had incurred his displeasure. They can see the crooked smile curl the lip of this cruel monster as he views the grim spectacle of human bodies hanging by the neck, but can they hear the heart-rending shrieks of ninety little children as they burn to death at Calumet, Michigan?

We shall learn that in no country under the sun has the working class been subject to more torture, more agony, than in America. There the warp and woof of social life is stained with the tears and died with the blood of the working class.

That “Justice” is no abstract thing, but so far has always been a weapon in the hands of the powers that be can be illustrated from the history of the early colonists.

In the theocratic autocracy that ruled the in old Massachusetts, only the free planters had a share in making the laws of the colonies. The mass of the people, indentured slaves, and other workers, had nothing to say, but were forced to submit to the combined power of church and state. On May 13, 1640, an order of the General Court of Massachusetts “to ascertain what men and women were skillful in breaking, spinning and weaving…and to consider with those skillful in that manufacture what course may be taken to raise the materials and produce the manufacture,” marks the beginning of the textile industry in New England, and its proletariat. A law was passed limiting wages to 2 shillings a day.

In 1638 the colonies in Connecticut combined into one commonwealth “to maintain and preserve the liberty and purity of the gospels of our Lord Jesus… and also the discipline of the churches,” and chose a Governor and six magistrates. The constitution of 1638 and laws of the code of 1650 show the complete identity of the state with the church and the iron control by the small ruling group of free planters. We have modernised the spelling in the following quotations:

FROM THE CODE OF 1650

“Forasmuch as many ·persons of late years have been and are apt to be injurious to the goods and lives of others, notwithstanding all care and means to prevent and punish the same: It is therefore ordered by this court and authority thereof, that if any person shall commit Burglary by breaking up any dwelling house or shall rob any person in the field or highways, such a person shall for the first offense be branded on the forehead with the letter B; if he shall offend in the same kind a second time he shalt be branded as before and also severely whipped, and if he shall fall into the same offence a third time he shall be put to death as being incorrigible; and if any person shall commit such Burglary or rob in the fields or house on the Lord’s day, besides the former punishments, he shall for the first offence have one of his ear cut off and for the second offence he shall lose his other ear in the same manner; and if he fall into the same offence the third time he shall be put to death.”

Such was the beginning of the wonderful “Democracy.” We will now pass to another period in our survey of Class Justice. A period that is still not closed.

SLAVERY

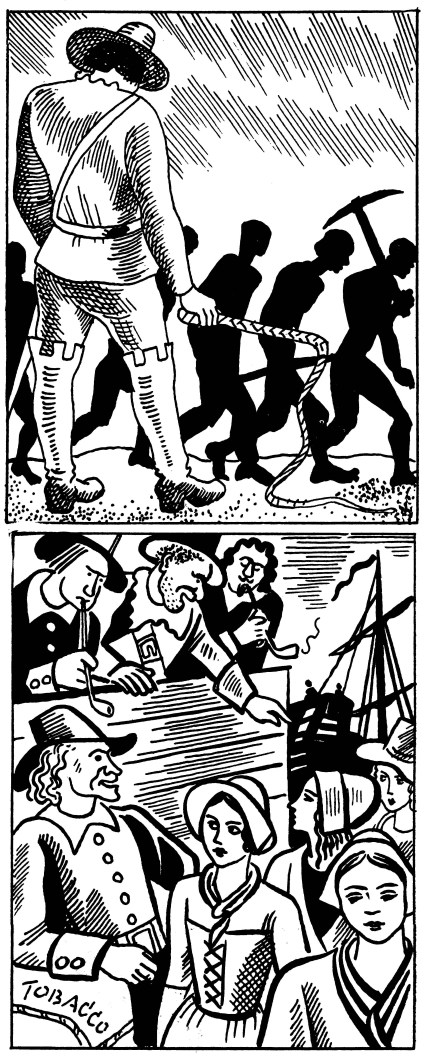

Those who ruled the colonies in America were members of chartered companies which had grants that provided “all the land, woods, soil, grounds, havens, ports, rivers, mines, marshes, fishing, commodities, hereditaments whatsoever.” For these, servile labor was: necessary and was provided in the form of indentured slaves from England and other countries.

There were several classes of slaves. One step above the black slaves were the convict bond-servants, or men and women in. a state of temporary, involuntary servitude. These people were mostly political offenders with some felon convicts. Those guilty of political offences were the Scots taken in battle in 1650, prisoners captured in the battle of Worcester in 1651, Monmouth’s men, 1685, the Scots concerned in the uprising of 1678, the Jacobines, 1760…Four thousand are known to have been sent to America. Felons formed the great source of supply. Twenty thousand came to the colony of Maryland, half of them after 1750. Between 1715 and 1775 ten thousand felons were sent from Old Bailey prison in London.

But the indentured servants and redemptioners did not cease to come when the colonies became the United States. Indentured servants were men, women and children, who, unable to pay their passage, signed a contract called an indenture. This bound the owner or master of the ship to transfer them to America. On reaching port the owner or master whose servants they became, as they had agreed to serve for a certain number of years, sold them for their passage, to the highest bidder.

The redemptioner was an immigrant who signed no indenture, but agreed with the shipping merchant that he be given a certain time in which to find somebody to redeem him by paying the freight. Should he fail to find a redeemer within a specified time, the captain was at liberty to sell him to the highest bidder. When a ship loaded with immigrants reached port, they were marched at once to a magistrate and forced to take an oath of allegiance to the United States and then marched back to the ship to be sold. If there were no ready purchasers, they were sold to speculators who drove them, chained together, in the country from farm to farm in search of a purchaser.

The contract signed, the newcomer became in the eyes of the law, a slave, and in both the civil and criminal code was classed with slaves and Indians. None could marry without consent of the master or mistress, under penalty of the addition of one year to the time set forth in the indenture. They were worked hard, wore cast-off clothing, and could be flogged as often as the master or mistress thought necessary. Father, mother, and children could be sold to different buyers. The only difference between these white slaves and black chattel slaves was, that the whites were sold for a limited time and the black slaves were sold for life. White and black slaves formed the basis for the landed aristocracy of the colonies before and long after the revolution. Paupers were sold at public auction in Boston and other New England towns. The states of New Jersey and New York followed the example. Children were sold as apprentices. This class of indentured servants as not recruited from immigrants alone. The courts of this period, 1684, and for years afterwards, sentenced freemen to be sold into servitude for a period of years to liquidate fines or other debts.

The life of an indentured slave was hard and cruel. Laws directed against disobedience and misdemeanors of white slaves were rigorous. Those calling for the severest punishments were offences against property. For the stealing of flour given for baking purposes offenders had their ears sliced off. Fugitive slave laws as applied to these slaves were a part of the legislation in all colonies.

The following advertisement is from the Virginia Gazette, July 14, 1737: “Ran away some time last lune from William Pierce of Nasimond county a convict servant woman named Winifred Thomas. Welsh, short, young, black-haired, marked on the inside of right arm with gunpowder, ‘W T’ and the date of the year underneath. She knits and spins and is supposed to be gone by the way of Cureatuk and Roanoke inlet. Whoever brings her back to her master, shall be paid a pistole besides what the law allows.” This woman slave had her initials and the date when she was purchased branded on her right arm. An instance is told of a man in Philadelphia, who wanted to buy an old couple tor house-servants. An old man, his wife and daughter were offered, and after paying the price he discovered he had bought his father, mother, and sister.

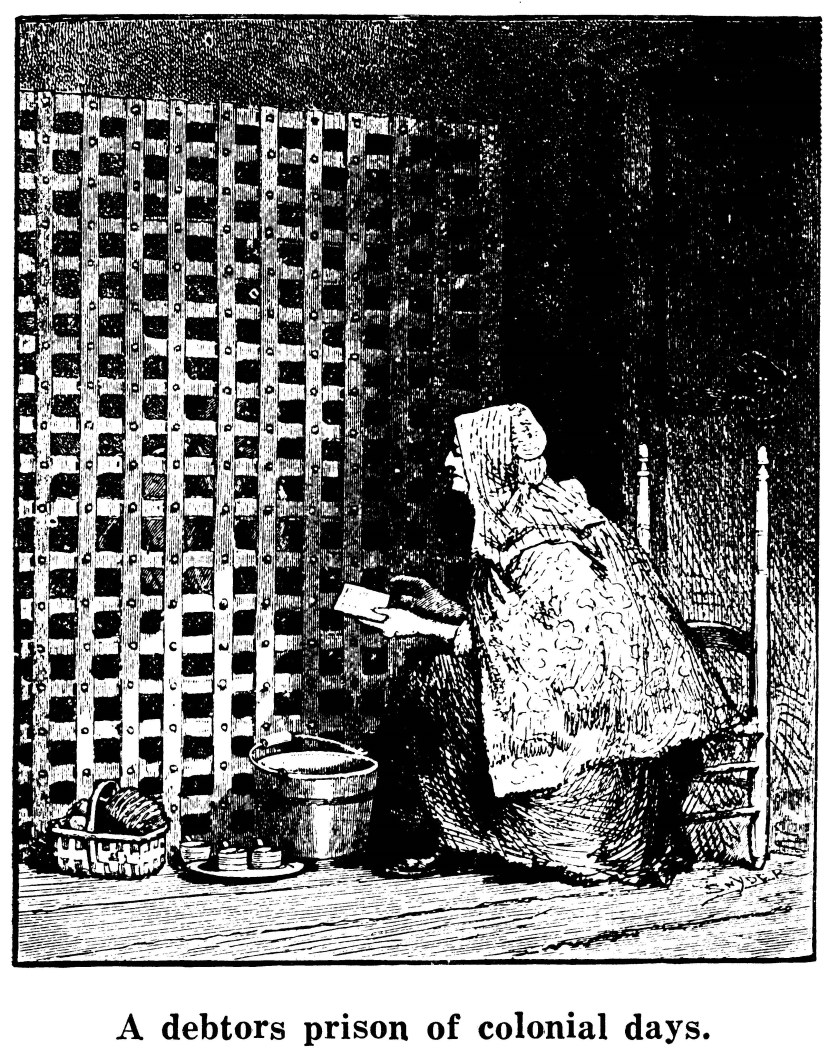

Indentured slaves who had served their time and secured their release, with the free immigrants out of employment, found themselves in a helpless condition with the result that they frequently became indebted in small amounts to the ruling class. Indebtedness became a crime. The method of dealing with this situation was to imprison the debtor until the debt was paid. It is said that seventy-five thousand people every year were placed in prison for debt in the different colonies and after they became the United States. While confined their support depended upon friends or charitable organizations. The suffering that they endured for an unavoidable offence was horrible in the extreme. One historians says:

“Our ancestors, it is true, put up a just cry of horror at the brutal treatment of their captive countrymen in the prison ships and hulls, yet even then the face of the land was dotted with prisons where deeds of cruelty were done in comparison with which the foulest acts committed on the ships and the hulls sink to a contemptible insignificance. For more than fifty years after the peace there was in Connecticut an underground prison. This den, known as the Newgate prison, was an old worked-out copper mine in the hills near Granby. There, in little pens of wood from thirty to a hundred culprits were immured, their feet made fast to iron bars and their necks chained to beams in the roof. The darkness was intense, the caves reeked with filth, vermin abounded, water trickled from the roof and oozed from the sides of the cavern. Masses of earth were continually falling. In the dampness and the filth the clothing of the prisoners grew moldy and rotted away, and their limbs became stiff with rheumatism.”

The Newgate prison was perhaps the worst in the country, yet in every county were jails such as would now be thought unfit places of habitation for the vilest and most loathsome of beasts.

When the ruling class of America proved to its own satisfaction that black slaves were more profitable for plantation labor than white servitors, the condition of the whites became even more deplorable than that of the black slaves. The white worker was deprived of employment, disfranchised and rendered practically helpless, as he was denied access to the land. All of the colonies adopted black slavery and in New England shipping interests created a vicious triangle. Ships loaded with rum were sent to the shores of Africa and there traded for slaves who were brought to the colonies of the South or Jamaica where they were exchanged for molasses which was in turn carried to the manufacturing centers of New England where distillers converted it into rum. Historians say that 200,000 slaves were transported to America, a half million people were stolen from their homeland, the larger percentage of whom died at sea.

In slave-warehouses on the west coast of Africa, Negroes were kept awaiting shipment. They were packed into ships, chained together, crouching or lying in the smallest possible space. Twice a day they were led to the decks for air, but the rest of the time they sweated and smothered in the dark hole, the sick and dying chained to the survivors, in filth and misery. Fearful diseases broke out, smallpox and opthalmia among them. The blind and the dying were thrown to the sharks, being useless to the trader. Acaptain counted on losing one fourth of his cargo, sometimes losing a great deal more.

For a time the status of the black slave was not definitely settled. In 1662 Virginia passed an act declaring that the status of a child should follow that of the mother, which act gave slavery legal recognition and also made it hereditary. The slave had none of the rights of the citizen. In criminal cases he could be condemned with but one witness against him and could be sentenced without trial by jury. The question of whether one Christian could hold another in bondage was settled in 1667 with the decision that the conferring of baptism did not alter the status of a person as to his bondage or freedom. In 1669 an act “about the casual killing of slaves” provided that if a slave who resisted his master chanced to die under punishment his death was not a felony and the master was to be acquitted. In 1670 it was enacted that only freeholders and householders should vote. In 1705 Negro, Mulatto and Indian slaves within the dominion were declared to be “real-estate” and “incapable in law to be witnesses.” In 1723 in an act for the “more effectual punishing of conspiracies and insurrections” it was specified that no slave should be set free on any’ pretext except “some notorious service to be adjudged and allowed by the governor and council.”

After the above-mentioned act of 1705 naming the slaves. “real estate” the black slave in America was no longer a person but a thing.

There were so many slaves in Virginia, which was then a much larger dominion than is the state of that name today, that they formed a menace to the white ruling class. Therefore the laws and customs directed against the Negroes became more drastic. They were branded like cattle, it was against the law to teach them to read, they could not leave the plantation on which they worked. Masters were reimbursed by the government for slaves legally executed. In Massachusetts executions were by hanging, but in 1755 an obsolete law was revived to burn alive a slave woman who had killed her master.

When great numbers of Negroes were being brought from Africa, filled with resentment against the cruel treatment, and with the advantage of their native dialects, the planters began to live in constant fear of uprisings. By making favorites of the house servants, they kept spies among the field Negroes, and in this way discovered the various conspiracies and broke the rebellions that developed. In 1687, in 1710 and 1711 such conspiracies were detected. In 1712 in New York City eight or ten whites were killed and eighteen or more Negroes executed. Some were hanged and some were burned at the stake, many committed suicide in fear of torture. In 1720, 1722, and 1723 there were attempted rebellions in Savannah. In 1730 men from several counties had to be called to put down an uprising in Virginia. In 1739 a formidable insurrection broke out; thirty-four Negroes were killed, forty were captured, some of whom were shot, some hanged and some gibbetted alive. In 1740 in South Carolina the rebellion under Cato terrified the whites. The Negroes seized a warehouse from which they got arms and ammunition and marched with drums and banners, burning every house they came to, killing the whites and gathering the Negroes into their company. Finally they were surrounded by militia and captured after a battle. All the leaders were executed. This was the occasion of the severe Negro Act of 1740. This was also the period of uprisings at sea in the slave-ships.

In 1741 in New York City there was a great insurrection. A plot to burn the town was discovered and 20 whites and 154 Negroes were arrested. Four whites and 31 Negroes were executed, some by burning and some by hanging, and seventy-one were transported.

After Gabriel’s insurrection in 1800 in Virginia 36 Negroes were executed, some “by mistake.”

There was no effort to improve the condition of the negro during the dark days of his captivity. Negroes were “cattle who could talk,” and were bred as such for the market. It was when this breeding of Negroes for the market developed that real activity against the importation of slaves from Africa began. Negroes born in America were more docile and less resentful, and the slave-breeders did not want the imported article to compete with their wares.

In 1800 Denmark Vesey, in Charleston, won enough in a lottery to buy his freedom and set himself up as a carpenter. He came to have great influence among the slaves. In 1812 he chose eight assistants for his great plan, courageous and intelligent men who recruited rebels on the neighboring plantations and in the town. Just before the date fixed upon, the uprising was betrayed, and thirty-four men were condemned to die in consequence: in all, one hundred and thirty-one were arrested, thirty-five executed and forty-three banished.

Nat Turner, in 1831 led a rebellion, which so impressed the whites that it resulted in systematic terrorising of the Negroes. A party rode from Richmond with the intention of killing every Negro in the county. They tortured and maimed indiscriminately, set up heads on poles to terrify the survivors. Twenty leaders of the rebellion were executed and twelve transported.

With the development of factories in the northern states, the control of the government by the slave-owning southern states became a heavy handicap to the country as a whole. The Abolition movement began, meaning the movement for the abolition of slavery. The Abolition movement was the expression of the country’s need to change from chattel slavery to wage slavery. Chattel slavery and its interests were crippling the industrial development of America. Escaped slaves joined in the work, for example Frederick Douglass, who became one of the greatest orators and writers of the movement after escaping at the age of twenty-one from slavery in the south. He was almost the only leader of this movement who came near to understanding the revolutionary significance of the changes that were taking place.

The Abolitionists called the attention of America to the slave who for running away was for five days buried in the ground up to his chin with his hands tied behind him; to women who were whipped because they did not breed fast enough or would not yield to the lust of planters or overseers; to the Presbyterian preacher in Georgia who tortured a slave until he died; to a woman in New Jersey who was bound to a log, scored with a knife across her back, and the gashes stuffed with salt, after which she was tied to a post in a cellar, where, after suffering three days, death kindly terminated her misery.

The Dred Scott case in 1848 aroused intense excitement. Scott was a slave who claimed that his residence with his master in Illinois and Missouri, free states, had made him a free man. After some time the case reached the Supreme Court of the United States, which decided that “the Negroes are so far inferior that they have no rights which a white man is bound to respect,” that Scott was a piece of property, and that his master might take him anywhere he pleased with impunity.

In 1859 John Brown, a rebel against slavery, made an armed raid on Harpers Ferry, for which he was hanged. In 1860 the Civil War broke out between the industrial north and slave-holding south, ostensibly to free the black slaves. Hundreds of thousands of lives were sacrificed, and every blow struck to break the bonds of chattel slavery more securely welded the chains of the wage slavery upon black and white workers alike.

The burden and tribulation of the black slave continued long after the emancipation proclamation; in fact continues to the present day, as will be shown by the examples given. Massacres, lynchings and race riots accompany the struggle of the Negroes to achieve a place as freemen in the life of America.

In 1876 the aggressiveness and violence of the arrogant whites brought about the Hamburg Massacre in South Carolina, in which many Negroes were killed and the white mob of several hundred mounted men terrorized the survivors into swearing that they would never bear arms against white people nor give in court any testimony regarding the massacres; the chief of police was murdered for interfering, and the mob finally wrecked the homes of the most prosperous Negroes in the town.

As we have said above, the courts are white, and the Negroes cannot serve on juries. The police, judges and juries are all white, and the Negro knows beforehand that the case will be decided against him. Lynchings grew apace; any cause of controversy however slight that forced the Negro to defend himself against the white man might result in a lynching with all its hideousness. Between 1885 and 1915 there were 3500 lynchings in the United States, the greater majority of victims being Negroes in the south. In 1892 alone the number was 325.

In 1909 a Pullman porter was falsely arrested for stealing $20. After his discharge as innocent he sued his accuser for damages. The judge reduced the award to one eighth of what the jury had given him, saying that “a Negro when falsely imprisoned did not suffer the same amount of injury that a white man would suffer.”

“Divide and Conquer” has been the slogan of the ruling class since ancient Rome enslaved the barbarians. It is still the slogan used against the working class of all races. When the working class realizes this, it will unite against this oppression; it is this that the rulers fear, and it is this that they take every means, however brutal to prevent.

Labor Defender was published monthly from 1926 until 1937 by the International Labor Defense (ILD), a Workers Party of America, and later Communist Party-led, non-partisan defense organization founded by James Cannon and William Haywood while in Moscow, 1925 to support prisoners of the class war, victims of racism and imperialism, and the struggle against fascism. It included, poetry, letters from prisoners, and was heavily illustrated with photos, images, and cartoons. Labor Defender was the central organ of the Scottsboro and Sacco and Vanzetti defense campaigns. Editors included T. J. O’ Flaherty, Max Shactman, Karl Reeve, J. Louis Engdahl, William L. Patterson, Sasha Small, and Sender Garlin.

PDF of issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/usa/pubs/labordefender/1936/v12-%5B10%5Dn04-apr-1936-orig-LD.pdf